Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Kanti R. Rai, MD  Jacqueline C. Barrientos, MD

Jacqueline C. Barrientos, MD

Overview

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an indolent B-cell neoplasia characterized by a progressive accumulation of small functionally incompetent lymphocytes in the blood, marrow, and lymphoid tissues. Given its indolent presentation, initiation of therapy is deferred until patients become symptomatic. CLL primarily affects the elderly population who generally has clinically significant coexisting conditions. The use of traditional chemoimmunotherapy regimens has been historically limited to fit patients able to tolerate the known toxicities from such regimens. A major shift in the management of CLL is currently taking place with the approval of several new targeted agents with unprecedented clinical activity in patients with poor prognostic markers and high-risk disease. New drug combinations are being evaluated with the goal to optimize treatment approaches based on the clinical and biological profile of the CLL patient.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

CLL biology: Historical perspective

CLL is a monoclonal CD5+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder derived from antigen-experienced B lymphocytes that differ in their level of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) gene mutations.1 Table 1 summarizes some of the important differences between the way CLL is defined now and in the past. The pace of research in CLL received a major boost over the past decade with the finding of chromosomal abnormalities and genetic mutations that contribute to the heterogeneity of the clinical presentation and help predict the disease course. Equally important has been the discovery of the role of the microenvironment and of the signaling factors that are necessary to CLL pathogenesis.2–5 This greater understanding has led to the development of agents that specifically target dysregulated pathways that allow the proliferation and survival of the malignant clone. The recent introduction of therapies with excellent clinical activity in patients previously refractory to chemotherapy is changing the natural history of the disease with long-term survival expectations substantially improved. Despite these rapid advances, the majority of CLL patients who initially achieve a remission eventually relapse. Presently, research is focused on elucidating mechanisms of resistance to the novel targeted agents.

Table 1 B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia as viewed then and now

| Previously | Currently |

|

|

Incidence and epidemiology

CLL is the most prevalent adult leukemia in the Western world accounting for approximately 30% of all leukemias diagnosed in the United States. Approximately 15,720 new cases of CLL and 4600 deaths are expected in the United States in 2014.6 For the most part, CLL is a disease of the elderly, with a median age of 71 years at diagnosis. The male : female incidence ratio of CLL is approximately 1.5 : 1.6, 7 CLL is more common in Europe, Australia, and North America than in Asia, Africa, or other less developed countries.8

Diagnosis of CLL

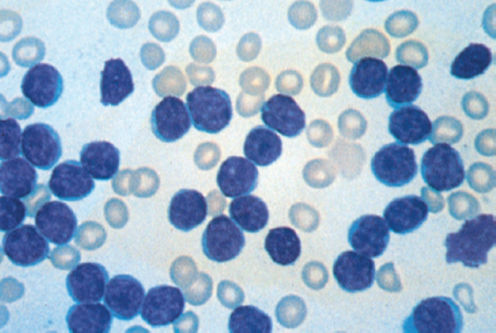

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematopoietic tumors describes CLL as a leukemic, lymphocytic lymphoma, distinguishable from small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) only by its leukemic presentation.9 In this classification, CLL is always a disease of neoplastic B cells, while the entity formerly known as T-CLL is now called T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL).10 The International Workshop on CLL (IWCLL) established the diagnosis of CLL as requiring the presence of at least 5 × 109 clonal B lymphocytes/L (5000/μL) in the peripheral blood confirmed by flow cytometry.11 Peripheral blood smear review reveals small, mature lymphocytes with a narrow border of cytoplasm (Figure 1). Gumprecht nuclear shadows, also known as “smudge cells,” can be found as debris. The nuclear chromatin is clumped and exhibits partially aggregated chromatin with up to 55% larger or atypical cells, cleaved cells, or prolymphocytes.12

Figure 1 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia morphology in peripheral blood smear. Leukocyte count: 100 × 109/L. Most of the lymphocytes are mature appearing. One smudge cell is present. Platelets are absent in this thrombocytopenic patient (Wright-Giemsa stain; ×100 original magnification).

Pathogenesis and causation

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and familial CLL

The absence of cytopenias, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or disease-related symptoms (B symptoms) in the presence of fewer than 5 × 109 clonal B lymphocytes/L in the peripheral blood is defined as “monoclonal B-lymphocytosis” (MBL).13 Rawstron and colleagues14 found MBL among 13.5% of normal first-degree relatives of people known to have CLL. That incidence is much higher than the 3.5% that Rawstron and colleagues discovered among adults with normal blood counts without a first-degree relative with CLL.15 Furthermore, there is an increased incidence of CLL or related disorders among the family members of people known to have CLL.17, 16 Further research is needed to elucidate a putative CLL predisposition gene or a possible CLL carrier state. Similar to Kyle’s MGUS data in multiple myeloma,18 the rate of progression to CLL that requires treatment is 1.1% per year.19

Immunobiology and immunophenotype of CLL cells

Morphologically, CLL cells resemble mature lymphocytes in the normal peripheral blood and coexpress the T-cell antigen CD5 with the B-cell surface antigens CD19, CD20, and CD23. The levels of surface immunoglobulin, CD20, and CD79b are characteristically low compared with those found on normal B cells,20 with the clones restricted to expression of either kappa or lambda immunoglobulin light chains. Several other malignancies of mature-appearing lymphocytes (Table 2) present with clinical features overlapping those of CLL; hence, flow cytometry is extremely helpful in distinguishing CLL from other diseases (Table 3).21–23

Table 2 Malignancies of morphologically mature-appearing B lymphocytes

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) |

| B-prolymphocytic leukemia (B-PLL) |

| Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) |

| Follicular lymphoma in leukemic phase (FL-L) |

| Mantle cell lymphoma in leukemic phase (MCL-L) |

| Splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes (SLVL) |

| Lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma |

Table 3 Phenotypes of lymphoproliferative disorders

| Disease | Typical phenotypes |

| CLL | CD20 (d), CD19+, CD22 (d), sIg (d), CD23+, FMC-7−, CD5+, CD10−, CD38+/− |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | CD20 (i), sIg (i), CD23+/−, FMC-7+/−, CD5+, CD10−, cyclin-D1+ |

| B-prolymphocytic leukemia | CD20 (+i), sIg (+i), FMC-7+/−, CD5+/−, CD10− |

| Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma | CD23−, CD11c+/−, CD103+/−, CD5+/−, CD10−, CD138 (b) |

| Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma | CD23(-/d), sIg+/−, cIg+, CD5+/− |

| Follicular lymphoma | CD20 (+i), CD5−, CD10+, bcl-2+, CD43− |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | CD20 (+i), CD5−, CD10+, bcl-2+/−, CD43+/−, CD5+/− |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | Bcl-2−, CD10 (+b), CD43+, CD5− |

| Hairy cell leukemia | CD20 (b), CD22 (b), CD11c (b), CD25+, CD103+, sIg (i), CD123+, CD5− |

Abbreviations: +, usually positive; −, usually negative; +/−, may be positive or negative; d, dim; i, intermediate; b, bright; sIg, surface immunoglobulin; cIg, cytoplasmic immunoglobulin.

Clinical aspects

Patients infrequently present with constitutional symptoms. The classic symptoms are known as “B symptoms”: unintentional weight loss of 10% or more, fevers higher than 100.5°F (38°C), or night sweats for more than 1 month without evidence of infection. Fatigue may also be reported.

Absolute lymphocytosis in blood

By IWCLL criteria, the presence of at least 5 × 109 B clonal lymphocytes per liter (5000/μL) with the phenotypes CD19+, CD20+, CD23+, and CD5+ is required to diagnose CLL, as lymphocytosis may occur with infections or in other neoplastic conditions (e.g., leukemic phase of lymphomas, hairy cell leukemia (HCL), PLL—Figure 2, and large granular cell leukemia).

Figure 2 Prolymphocytic leukemia. Peripheral blood smear shows cells with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm (Wright-Giemsa stain; ×1000 original magnification).

Clinical presentation

Upon physical examination, a CLL patient may have enlarged nodes that are firm, rounded, discrete, nontender, and freely mobile upon palpation. The most consistent abnormal finding on physical examination is lymphadenopathy, but splenomegaly or hepatomegaly may also be present. Enlargement may be generalized or localized, and degree can vary widely leading to obstruction of adjacent organs. In addition to palpably enlarged peripheral lymph nodes, liver, and spleen, virtually any other lymphoid tissue in the body—for example, Waldeyer’s ring or the tonsils—may be enlarged at diagnosis. In addition, infiltration with CLL cells may occur in any organ or tissue. In contrast to lymphoma, gastrointestinal mucosal involvement is rarely seen in CLL. Similarly, meningeal involvement is extremely unusual.

Radiologic findings

Radiologic examinations are neither required nor recommended as part of an evaluation at the time of initial diagnosis or during routine follow-up. Computed tomography (CT) scans or chest films will often reveal adenopathy not detected on examination, but these findings do not change the clinical Rai or Binet stage. Unless there is a specific clinical question brought up by a new symptom or complaint, we recommend not doing these procedures. The American Society of Hematology embarked on the “Choosing Wisely” campaign to advocate clinical staging and blood monitoring in asymptomatic patients with early-stage CLL rather than performing CT scans. In the setting of a therapeutic research protocol, imaging may be obtained for specific protocol-related purposes.

Laboratory abnormalities

Although the absolute blood lymphocyte threshold for diagnosing CLL was placed at 5 × 109/L, most patients present with considerably higher counts, occasionally even in the hundred-thousand range. Upon examination of a peripheral blood smear, mature-appearing small lymphocytes may be preponderant in the population of leukocytes, ranging from 50% to as much as 100%.

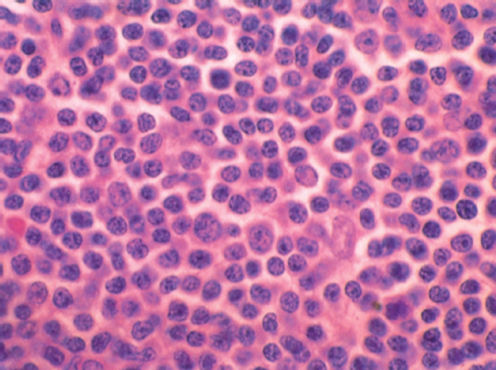

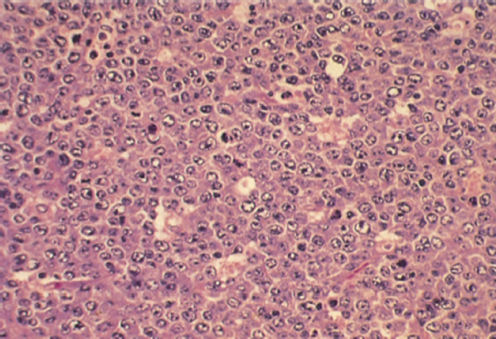

In addition to an increased ratio of mature-appearing lymphocytes in the smears of aspirated marrows, three patterns of infiltration by lymphocytes are recognized in trephine biopsy specimens of the bone marrow ( Figure 3): nodular, interstitial, and diffuse. It has been observed that patients with diffuse infiltration tend to have advanced disease and worse outlook. For prognostic purposes, nodular and interstitial patterns, which are associated with less-advanced disease and better prognosis, are grouped together and termed “nondiffuse.”24–26

Figure 3 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Marrow biopsy with diffuse infiltration by CLL cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain; ×600 original magnification).

Asymptomatic anemia and thrombocytopenia may be observed at the time of initial diagnosis, but usually these are of a relatively mild degree. A direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test may be positive in ∼25% of cases, but overt autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurs less frequently. In the absence of a reliable test to demonstrate antiplatelet antibodies, autoimmune thrombocytopenia is most often diagnosed on the basis of the presence of adequate numbers of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow with abnormally low platelet counts.

Hypogammaglobulinemia may be present at the time of initial diagnosis, but it becomes clinically significant only later in the course of the disease. All three immunoglobulin classes (IgG, IgA, and IgM) are usually decreased, although in some patients only one or two classes may be reduced. Concurrent hypogammaglobulinemia and neutropenia result in increased vulnerability of CLL patients to severe bacterial, viral, and opportunistic infections. As a large proportion of cells are B lymphocytes, the normal lymphocyte T : B ratio (2 : 1) is altered. As patients are not immunocompetent, they should avoid inoculation of any live vaccines (varicella, measles, Bacille Calmette-Guérin, etc.). In this immunocompromised population, replication of the virus after administration can be enhanced and live vaccines can actually induce active infection.27, 28

No abnormalities in blood chemistry are characteristic of CLL, but increased levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, hepatic enzymes [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST)], and (rarely) calcium may be observed. Pseudohyperkalemia can occur occasionally in patients with extreme leukocytosis.

Natural history and terminal events

It is a generally held belief that CLL is an indolent disease with a prolonged chronic course and that the eventual cause of death may be comorbidities unrelated to CLL; however, this observation is true for fewer than 30% of all CLL cases. The natural history is heterogeneous in most patients. Many patients live for 5–10 years with an initial course that is relatively benign but that is almost always followed by a terminal phase lasting 1–2 years. During the initial asymptomatic phase, the patients are able to maintain their usual lifestyle, but during the terminal phase, performance status declines rapidly. In patients with progressive disease, the cause(s) of death are directly related to CLL or complications from therapy. Infection is a major cause of mortality in patients with CLL, accounting for 30–50% of all deaths.

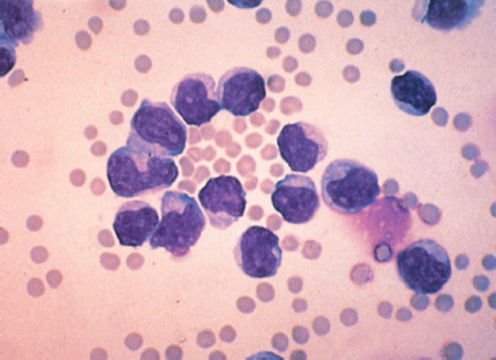

Transformations to a high-grade disease are characteristically refractory to usual chemotherapeutic agents.29 In up to ∼10% of CLL patients, a transformation to a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurs30 (“Richter’s transformation” or “Richter’s syndrome”; Figure 4). Richter’s syndrome is associated with a rapidly progressive course, refractoriness to all currently known chemotherapy, and poor overall survival (OS).31, 32 The diagnosis of Richter’s syndrome requires histopathologic examination of a lymph node that shows large B cells with high proliferative rate (high Ki-67). In addition, a small proportion of patients with CLL undergo “prolymphocytoid transformation,” and peripheral blood morphology reveals the presence of a mixture of small mature CLL cells and prolymphocytes in contrast to typical B-PLL (B-prolymphocytic leukemia) where the circulating cells are monomorphic prolymphocytes.33 Similar to a Richter’s transformation, prolymphocytoid transformation has an aggressive clinical course.

Figure 4 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Richter’s syndrome. Section of lymph node with immunoblastic proliferation consisting of large cells with prominent nucleoli (hematoxylin and eosin stain; ×600 original magnification).

Acute leukemia is observed extremely rarely in the setting of a CLL diagnosis. If it occurs, it is usually myeloid in origin (myelocytic, myelomonocytic, or acute erythroleukemia). Prior therapy with alkylating agents has not been clearly implicated as a cause because a few cases have been observed in treatment-naive patients. The acute leukemia is treated with an acute leukemia regimen, although almost invariably the outcomes are very poor.

Patients with CLL have been found to have over twice the risk of developing another cancer compared to the general population.31 Skin cancers and other malignancies occur with considerably greater frequency among CLL patients. We recommend that all CLL patients (including treatment-naive) adhere to age-appropriate cancer screening guidelines.

Clinical staging and other prognostic features

Two staging criteria, the Rai34 system and the Binet38 system, are widely used in clinical practice owing to their simplicity (only a physical examination and a complete blood count are needed) and accuracy in predicting outcomes.

Method of Rai and colleagues

The Rai system is based on the concept that in CLL, a gradual and progressive increase in the tumor burden of leukemic lymphocytes occurs, resulting in sequential clinical manifestations of the disease. The abnormalities start in the blood followed by the lymph nodes, spleen, and liver; to eventually compromise the bone marrow function. The earliest stage is blood lymphocytosis (clinical stage 0). The later stages (anemia and thrombocytopenia—excluding AIHA and ITP) are explained by progressively increasing bone marrow infiltration by CLL cells.

At the time of initial diagnosis of CLL, approximately 25% of patients are in the earliest clinical stage (stage 0), ∼25% are in the advanced stages (stages III and IV), with the remaining 50% in the stage I or II categories. Table 4 shows the stage distributions from various series, revealing a consistent pattern. The median survival times from the time of diagnosis in the Rai series were 150 months for stage 0, 101 months for stage I, 71 months for stage II, 19 months for stage III, and 19 months for stage IV.34 Although Rai and colleagues noted in their 1975 paper that only three (and not five) distinct actuarial survival patterns emerged from the data (stage 0, stages I and II combined, and stages III and IV combined), they recommended that the five-stage system be maintained to investigate prospectively whether biologic and clinical differences would emerge between stages I and II and between stages III and IV. In 1987, the Rai staging system was modified to consist of three groups: low (Rai stage 0), intermediate (Rai stages I and II combined), and high (Rai stages III and IV combined) risk categories.39 The modified Rai staging system was used for risk stratifying patients in the landmark study of chlorambucil against fludarabine in the front-line therapy of CLL conducted in the 1990s that established the superiority of fludarabine.40 Fludarabine and purine analogs are now part of the combination regimens for frontline therapy in fit patients with no major comorbidities.41, 42

Table 4 Distribution of cases in various series according to Rai staging

| References | Cases (n) | Series (years) | Stage (% of cases) | ||||

| 0 | I | II | III | IV | |||

| Rai et al.34 | 125 | 18 | 23 | 31 | 17 | 11 | 14 |

| Geisler and Hansen (1981)35 | 102 | 20 | 36 | 19 | 17 | 8 | 31 |

| Baccarani et al. (1982)36 | 188 | 26.5 | 26.5 | 21 | 9 | 17 | 9 |

| Skinnider (1982)37 | 745 | 19 | 21 | 31 | 16 | 13 | 31 |

| MRC CLL-1a (1989) | 660 | 28 | 18 | 29 | 10 | 15 | 31 |

a The hemoglobin level for stage III in Medical Research Council of Great Britain Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Trial I was <110 g/L.

Method of Binet and colleagues

Binet’s method classifies all patients with anemia (defined as hemoglobin below 100 g/L) and/or thrombocytopenia (platelets less than 100 × 109/L), or both, as stage C.38 All of the remaining (non-C) patients are divided into two groups, depending on the presence of fewer than three (stage A) or three or more (stage B) sites of palpable enlargement of lymphoid organs. This staging takes into consideration five sites: cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes (whether unilateral or bilateral, each area is counted as one), and the spleen and liver. This system has been found to be of great value in dividing patients into three types of survival curves, with A, B, and C corresponding, respectively, to Rai’s low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups.

Criteria predictive of disease course in the low- and intermediate-risk groups

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree