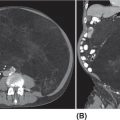

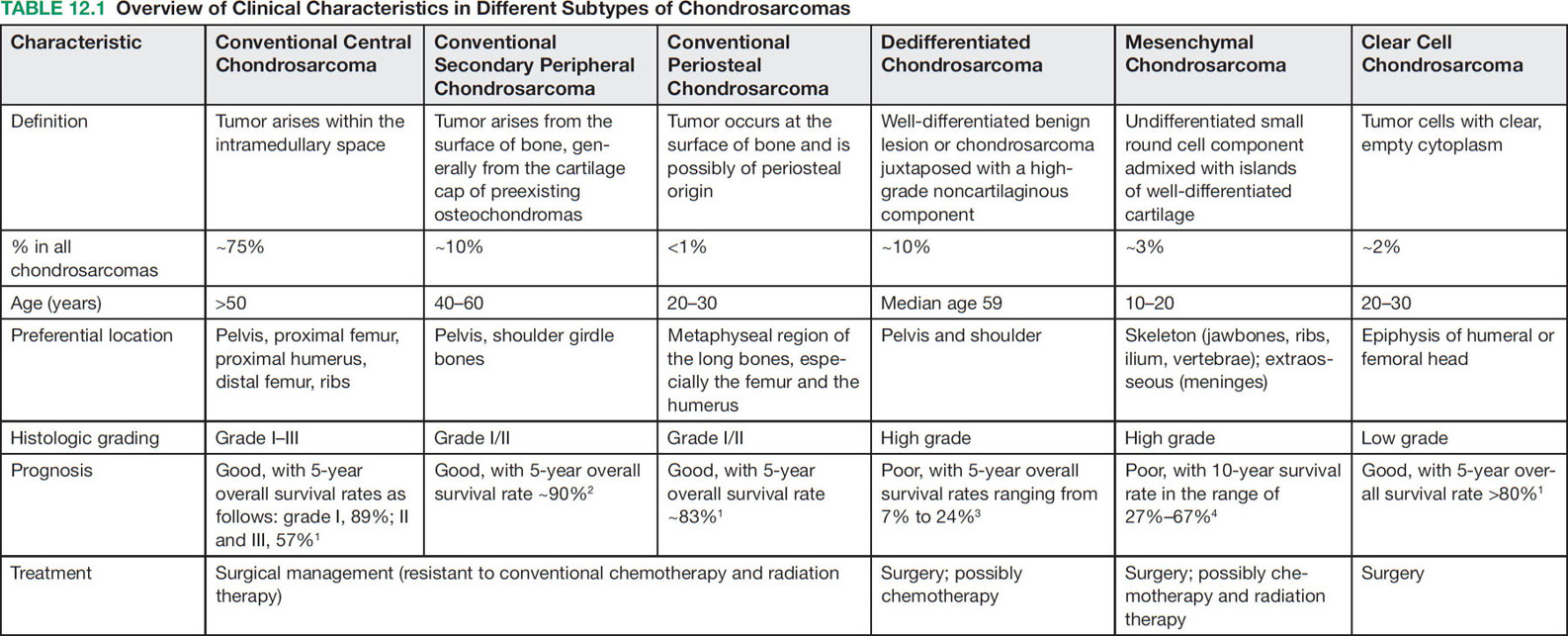

16112 Chondrosarcoma Chondrosarcomas constitute a heterogeneous group of malignant cartilaginous matrix-producing bone neoplasms with diverse morphologic features and clinical behavior. Following osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma is the second most common primary bone tumor, accounting for 20% to 27% of primary bone malignancy. Chondrosarcomas range from indolent, nonmetastasizing lesions to highly aggressive metastasizing sarcomas. Prognosis highly depends on the histologic grade of malignancy. Chondrosarcoma is poorly treatable because it is highly resistant to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgical resection remains the “gold standard” for the treatment of localized chondrosarcoma. Owing to lack of effective treatment, the clinical management of advanced chondrosarcomas is exceptionally challenging. Future studies should further explore the utility of these candidate molecular targeted therapies in advanced chondrosarcoma patients. This chapter presents the classification, clinical characteristics, and therapeutic options of all subtypes of chondrosarcomas, as well as the emerging novel therapeutic targets. chemotherapy, chondrosarcomas, clinical management, immunotherapy, Isocitrate dehydrogenases mutation, osteosarcoma, radiation therapy, surgical resection Chondrosarcoma, Drug Therapy, Immunotherapy, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase, Osteosarcoma, Radiotherapy INTRODUCTION Chondrosarcomas constitute a heterogeneous group of malignant cartilaginous matrix-producing bone neoplasms with diverse morphologic features and clinical behavior.1 Following osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma is the second most common primary bone tumor, accounting for 20% to 27% of primary bone malignancy.2 The incidence of chondrosarcoma steadily increases with age, with a peak incidence in the fifth to seventh decades and a slight male predominance. The most commonly involved sites are the bones of the pelvis, followed by the femur, humerus, and ribs.1 Most of the chondrosarcomas are sporadic, but they may develop from malignant transformation of two benign cartilaginous bone tumors, osteochondromas and enchondromas. Chondrosarcomas that arise de novo are called primary chondrosarcomas, while those superimposed on preexisting cartilaginous neoplasms such as enchondroma or osteochondroma are referred to as secondary chondrosarcomas.3 The cornerstone of the management of localized chondrosarcomas is surgical resection. The majority of chondrosarcomas grow slowly and rarely metastasize, and they have an excellent prognosis after adequate surgery. However, chondrosarcomas tend to recur following the initial tumor resection and over 10% of recurrent chondrosarcomas are of a higher grade than the original neoplasm.3 Many patients will eventually develop metastatic disease, which is nearly uniformly fatal in the absence of effective systemic therapy. The clinical challenge is to prevent recurrence and to find better treatment options for unresectable or metastatic disease. Here is a review of the classification, clinical characteristics, and therapeutic options of different subtypes of chondrosarcomas (Table 12.1), as well as the emerging novel therapeutic targets for this malignancy. HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES Pathologic subgroups include conventional and nonconventional chondrosarcomas; 85% to 90% of chondrosarcomas are conventional type, which can be subdivided into the central, peripheral, and periosteal subgroups according to the osseous location in the bone. The vast majority (>85%) are central chondrosarcomas, which arise within the intramedullary space. Primary central chondrosarcoma typically affects patients older than 50 years. Pelvis, proximal femur, proximal humerus, distal femur, and ribs are the most frequently involved sites. Secondary central chondrosarcoma develops as malignant transformation of enchondroma (very rare) or enchondromatosis, such as Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome. Patients with Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome have a 25% to 30% risk of developing chondrosarcoma.4 Peripheral chondrosarcoma (up to 15%) develops from the surface of bone, generally from the cartilage cap of preexisting osteochondromas. These are, therefore, referred to as secondary peripheral chondrosarcoma.5 Osteochondromas are cartilaginous-capped bony projections and usually occur on the external surface of long bones, tibial, and femoral bone, around the knee. Malignant transformation occurs in 5% of cases of osteochondromas, either solitary or multiple form.6 In addition, a minority (<1%) occur at the surface of bone, and are possibly of periosteal origin and designated as periosteal chondrosarcoma. This type tends to affect younger adults more often than other conventional types. The metaphyseal regions of long bones, especially the femur and the humerus, are most commonly affected. Histologically, conventional chondrosarcoma is subdivided as grade I, II, and III (low, intermediate, and high grade) by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining based on cellularity, matrix protein, and mitoses. Histopathologic grading is more related to tumor aggressiveness and disease prognosis. Grade I chondrosarcoma, now reclassified as an atypical cartilaginous tumor, shows low cellularity and is locally aggressive, but typically does not metastasize. Grade II and grade III conventional chondrosarcomas show increased cellularity with mitoses and reduced cartilaginous matrix, and a corresponding increase in metastasizing capacity alongside poor patient survival.7 Approximately 90% of conventional chondrosarcomas are low to intermediate grade (grade I–II) and behave indolently and rarely metastasize. Only 5% to 10% of conventional chondrosarcomas are grade III and have high metastatic potential.8 The main site of metastatic disease is lung, while the regional lymph nodes and liver are much less commonly involved.2 163Nonconventional chondrosarcomas are some specialized types with distinctive microscopic and clinical features, including dedifferentiated, mesenchymal, clear cell, and myxoid chondrosarcoma. They together constitute 10% to 15% of all chondrosarcomas. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma is a highly malignant variant of chondrosarcoma and accounts for up to 10% of all chondrosarcomas. The age of presentation is a decade older than that for conventional chondrosarcoma. It is characterized by two distinct histopathologic components: a well-differentiated lesion or chondrosarcoma (usually low grade) sharply juxtaposed with a high-grade, noncartilaginous component, which most frequently exhibits features of osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.7,9 Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is considered high-grade tumor type and accounts for approximately 3% of chondrosarcomas. It is characterized by a biphasic histologic pattern of undifferentiated small round cells admixed with islands of well-differentiated cartilage.3,10 The small cell component shows positive staining for SOX9 and negativity for FLI-1, which often helps in the differential diagnosis from Ewing sarcoma.10 HEY1–NCOA2 fusion gene has also been described in this subtype as a marker of diagnostic utility.11 Clear cell chondrosarcoma is a variant of conventional chondrosarcoma behaving as low-grade malignant bone tumor and involves a younger population than the conventional type. It accounts for about 2% of all chondrosarcomas, demonstrating tumor cells with clear, empty cytoplasm in addition to hyaline cartilage.7,8 Loss of p16 protein has been reported in patients with clear cell chondrosarcomas.12 Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma is a slow-growing soft tissue tumor containing prominent myxoid material, but it is considered a misnomer because it lacks cartilaginous differentiation.13 CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION Pain is nearly always present and is usually insidious, progressive, worse at night, and present for months to years prior to the patient seeking care. A palpable mass is frequently seen. Some patients present with pathologic fracture.14 Tumors located in the skull base can cause neurologic symptoms. Plain radiography is used for initial evaluation, which allows the identification of the cartilaginous nature and aggressiveness of the lesion. CT and MRI are essential for the determination of the extent of the intraosseous and soft tissue involvement preoperatively. Tissue biopsy by an experienced surgeon or interventional radiologist is essential to diagnose and differentiate the lesion from another malignant bone tumor. TREATMENT The radiologic and histopathologic classifications in relation to the clinical symptoms, medical history, and performance status are important for treatment decisions. Surgical treatment is the only option for curative therapy. Low-grade chondrosarcoma confined to the bone can be managed by extensive intralesional curettage with local adjuvant treatment such as phenolization or cryosurgery, followed by filling the cavity with bone graft.3,15,16 For intermediate- and high-grade chondrosarcoma, wide en bloc excision is the preferred surgical treatment.3,17 Tumors with intra-articular or soft tissue involvement, larger tumors, and axial or pelvic tumors must be treated with wide excision. However, in the event of tumor location at a nonresectable site, such as in the skull or pelvis, or a metastatic disease, there is no curative treatment. In general, chondrosarcoma is relatively resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiation therapy, possibly because of the low mitotic fraction of cells and restricted drug penetration as a result of the abundant extracellular matrix and poor vascularity.18 Chemotherapy is effective in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma10 but has limited value in dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Patients with primary mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated with an adult, small cell sarcoma regimen (see Chapter 13, Rhabdomyosarcoma) such as vincristine 2 mg, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 (over 72-hour infusion or bolus with dexrazoxane), and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 (divided over 4–5 days with mesna uroprotection) 164for six to eight cycles. On the other hand, primary dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma patients are generally approached like a poor-risk osteosarcoma (see Chapter 11, Osteosarcoma) using doxorubicin plus cisplatinum 90 to 120 mg/m2 intra-arterially (or intravenously [IV]), followed by high-dose ifosfamide 14 g/m2 for six cycles and high-dose methotrexate 12 g/m2 for six cycles. These agents are active in the metastatic setting as well. Radiation therapy can be considered after incomplete resection or if resection is not feasible or would cause unacceptable morbidity. However, doses >60 Gy are needed in attempts to achieve local control after incomplete resection. Unfortunately, application of this high-dose radiation therapy with conventional photon therapy is often not feasible, especially in chondrosarcomas arising in the skull base and axial skeleton. Irradiation with protons or other charged particles seems beneficial in this situation.3,19 Follow-up scans are extremely important for chondrosarcoma to make sure there has been no recurrence or metastasis. PROGNOSIS Prognosis highly depends on the histologic grade of malignancy. For conventional central chondrosarcoma, the 5-year survival rate by grade was 89% for patients with grade 1 and 57% for the combined group of patients with grades 2 and 3.4 The prognosis for patients with conventional periosteal chondrosarcoma is favorable compared to that of central type. The overall 5-year metastasis-free survival rate is approximately 83%.4 Most of the conventional peripheral chondrosarcomas are low grade and the overall prognosis is good, with long-term survival found in 70% to 90% of patients.4 However, despite adequate wide surgical resection and adjuvant systemic therapy, the prognosis for patients with a primary dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma is poor, with the 5-year survival rate reported to be between 7% and 24%.9 Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma shows a strong tendency toward late local and metastatic recurrences. Despite a potentially prolonged clinical course, the outcome for these patients ultimately appears to be poor, with reported 10-year survival rate in the range of 27% to 67%.10 NOVEL THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES Novel therapeutic approaches for patients with unresectable or metastatic disease are urgently needed. Current research focuses on elucidating the molecular events underlying the pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma and aiming at the development of new molecularly targeted therapies. The emerging pharmaceutical targets in chondrosarcoma include IDH mutation, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), angiogenesis, and Hedgehog (HH) pathway. Targeting IDH Mutations Isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDHs) are enzymes involved in tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) that catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate into alpha-ketoglutarate (alpha-KG). Mutant IDHs lose the capacity to convert isocitrate to alpha-KG, and instead gain a new function of reducing alpha-KG to an oncometabolite, D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG). IDH mutations have been observed in a variety of tumors including cartilaginous tumors.20 Intriguingly, these mutations are present in 87% of benign enchondromas, 38% to 70% of primary conventional central chondrosarcomas (central and periosteal), and 54% of dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas, but not in clear cell or mesenchymal chondrosarcomas.20,21 Therefore, IDH mutation represents a new common genetic abnormality in chondrosarcomas, indicating a potential role of this mutation in the pathogenesis of chondrosarcomas. The exact mechanism by which IDH mutation and D-2HG causes tumor formation is unknown, although increasing evidence points toward epigenetic mechanisms. The emerging concept is that the accumulated D-2HG competitively inhibits the function of alpha-KG–dependent dioxygenases involved in DNA and histone demethylation, which leads to a hypermethylation status of genome that affects the gene expression required for cellular differentiation.22 Inhibitors of mutant IDH1, IDH2, or both have been developed and evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies as single agents and in combination with other anticancer agents and have shown promising clinical benefits in some cancer types.23,24 It has been reported that a mutant IDH1 inhibitor showed antitumor activity in chondrosarcoma cell lines.25 Mutant IDH1 inhibitor AG-120 (NCT02073994), IDH2 inhibitor AG-221 (NCT02273739), and pan-IDH inhibitor AG-881 (NCT02481154) are currently being evaluated in patients with advanced IDH-mutant solid tumors including chondrosarcoma (Table 12.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree