Esophageal Cancers

The prevalence of esophageal cancer varies over 20-fold throughout the world. Esophageal cancer is most common in central Asia and remains relatively rare in the United States. Approximately 14,000 new cases of esophageal cancer occur annually in the United States, where 75% of esophageal cancers develop in men and only 25% in women.

HISTOLOGY OF ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

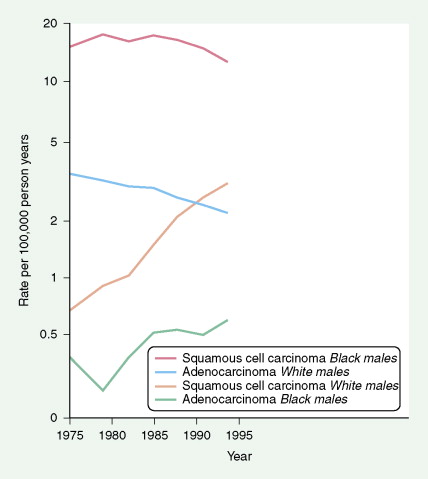

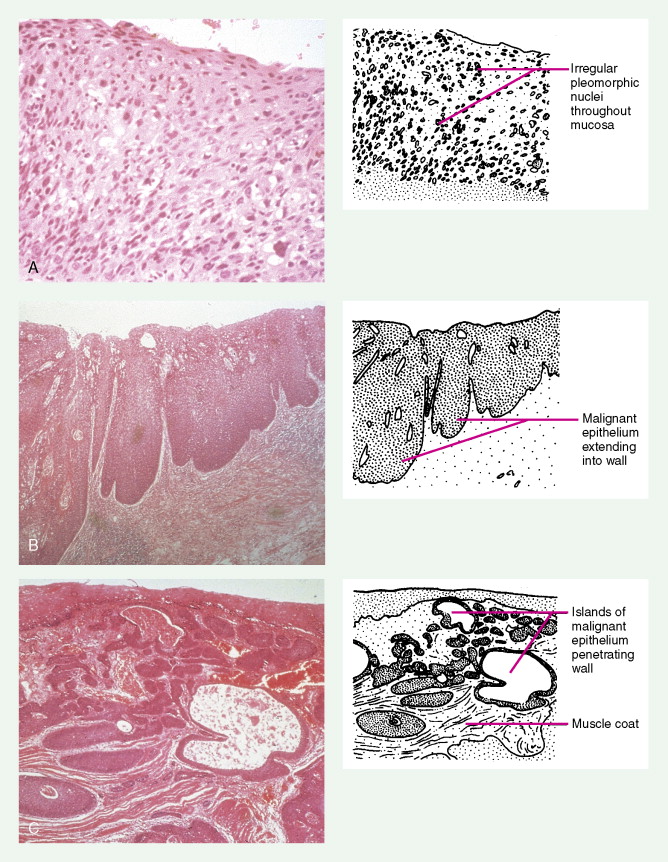

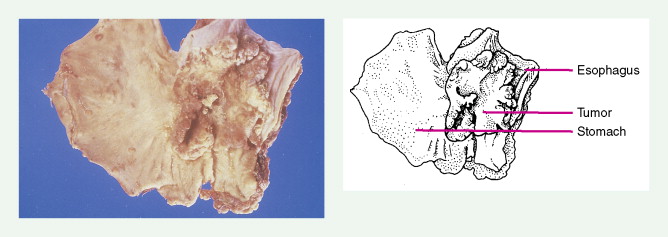

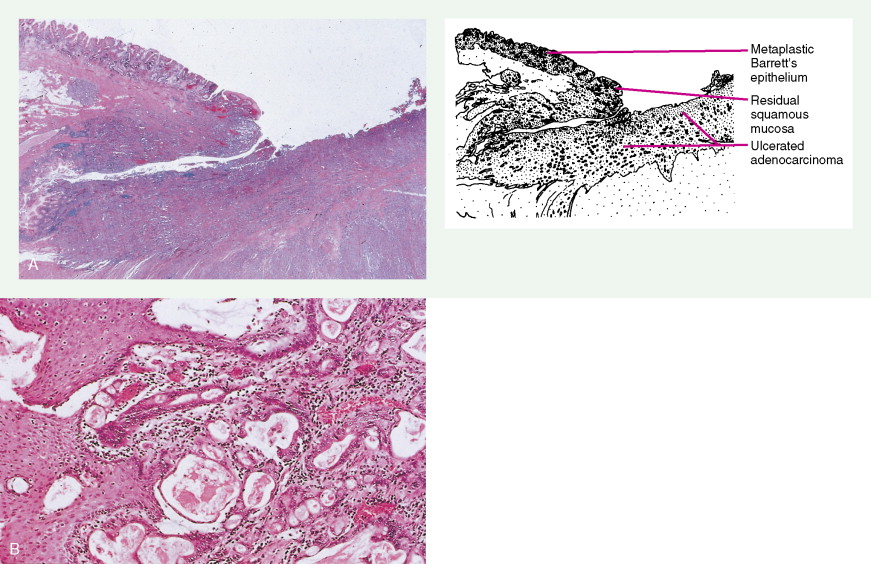

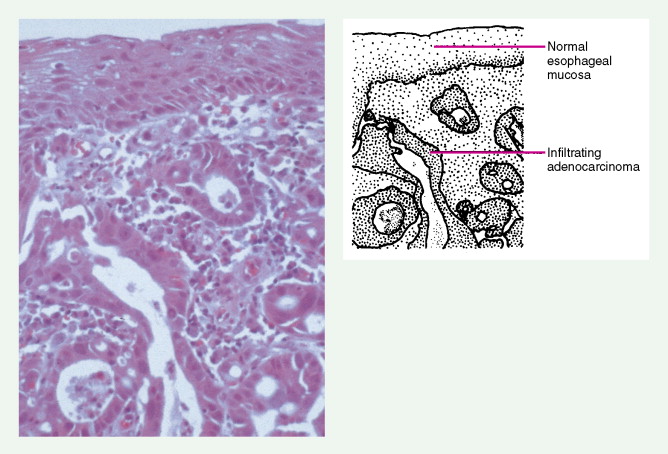

Worldwide, 90% of esophageal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. The risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is related closely to excessive alcohol consumption and chronic cigarette smoking. The squamous cell carcinomas, including spindle cell and verrucous variants, are most prevalent in the upper esophagus. Interestingly, in the past two decades the relative incidence of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has shifted markedly in both the United States and Europe. In these regions squamous cell carcinoma has become somewhat less common, whereas the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased to a considerable degree. In Caucasian males in the United States, for example, the incidence of adenocarcinoma now exceeds the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinomas of the esophagus generally occur in the distal third of the esophagus and are particularly common at the gastroesophageal junction. The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been closely linked to the presence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett’s esophagus.

In addition to tobacco and alcohol, other risk factors for squamous cell esophageal cancer include achalasia, history of cancer treated with radiation therapy in the mid- to upper chest region (e.g., breast cancer), tylosis, caustic injury to the esophagus, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome. In contrast, risk factors for the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus include gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett’s esophagus, obesity, prior radiation exposure to the mid- to upper chest, and smoking. Rare undifferentiated small cell carcinomas occur in the lower and middle esophagus. Risk factors for these unusual lesions have not been established. These highly malignant tumors behave like small cell lung cancers, occasionally producing paraneoplastic syndromes.

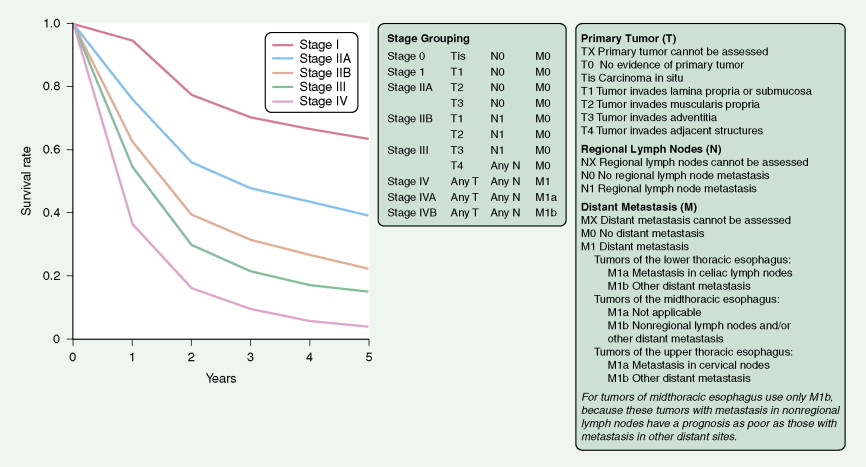

STAGING OF ESOPHAGEAL CANCERS

The unique structure of the esophagus is significant to the biologic understanding and clinical management of malignant disease. There is a rich lymphatic drainage throughout the length of the esophagus and a discontinuous serosa. Therefore, “skip areas” of micrometastases occur that necessitate wide surgical resection of operable tumors. Lymph node drainage varies within the esophagus (cervical vs thoracic). Nodal metastases frequently develop in mediastinal, para-aortic, and celiac lymph nodes.

In the TNM staging system (tumor, node, metastasis) commonly used for esophageal carcinoma, stages I and II represent operable disease, stage III denotes marginally resectable disease, and stage IV signifies inoperable cancer. The last stage is characterized by metastases (M1). About 15% of cancers originate in the upper third of the esophagus (cervical and upper thoracic esophagus), 50% in the middle third, and 35% in the lower third. The site of the primary tumor is critically important, because it relates to clinical behavior (adjacent organ involvement, nodal metastases) and technical resectability. Primary surgical resection is possible in about 40% to 50% of cases. About one third of patients are candidates for palliative surgery, and 20% to 30% present with unresectable stage III or IV disease. The 5-year survival rate is less than 5% for stage IV disease but is about 70% for stage I cancers.

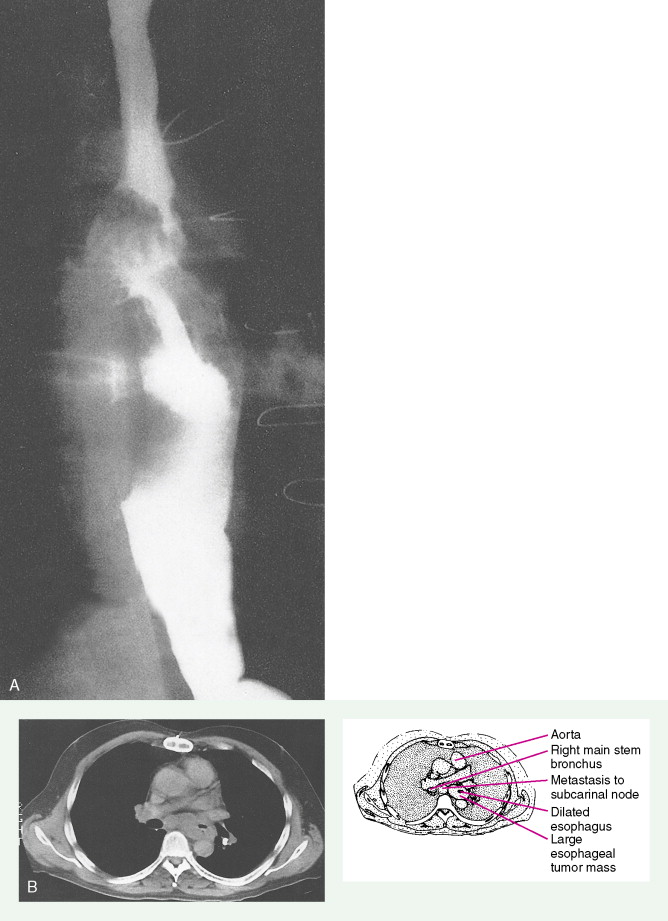

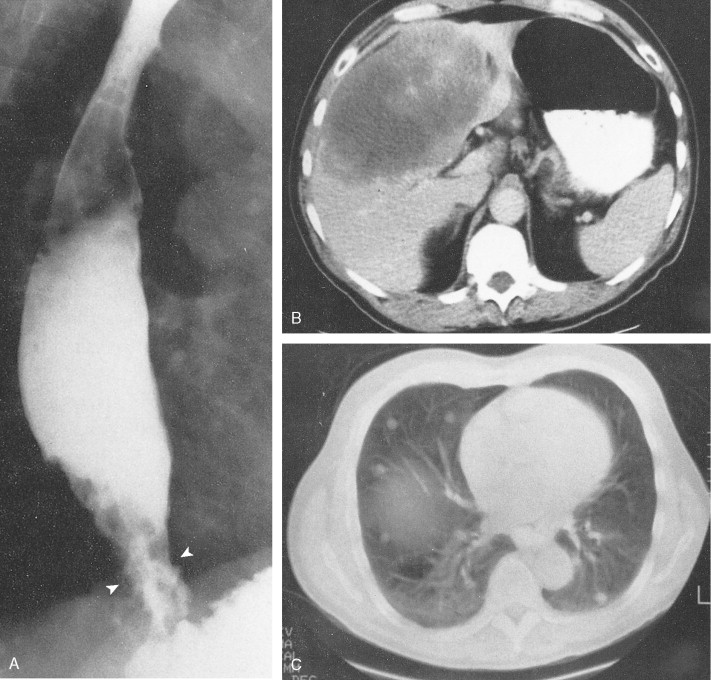

Staging procedures involve triple endoscopy, including detailed ear-nose-throat examination as well as bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy, because there is a high potential for development of other aerodigestive cancers because of similar risk factors. Mediastinoscopy, laparoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, liver, and upper abdomen are important to determine the presence of nodal or visceral metastases. Endoscopic ultrasound is helpful to determine the extent of invasion through the esophageal wall and involvement of regional lymph nodes. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning has been shown to be highly sensitive in detecting occult metastases from esophageal cancer and is being increasingly used as a staging procedure.

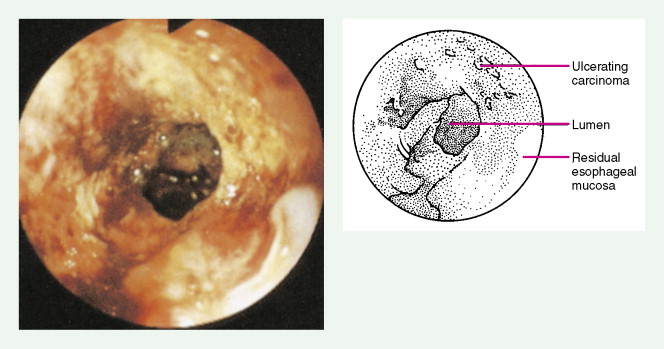

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

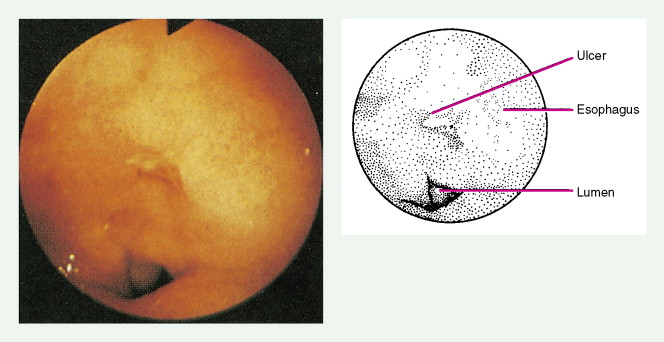

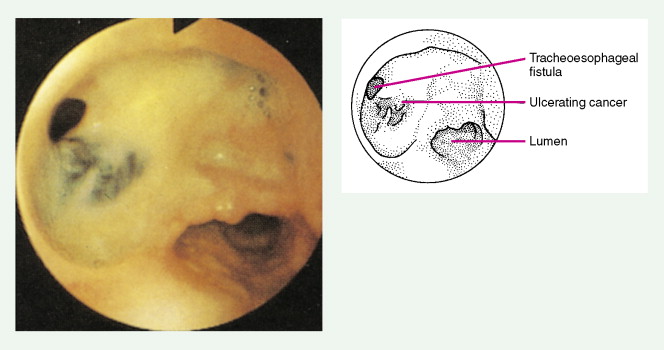

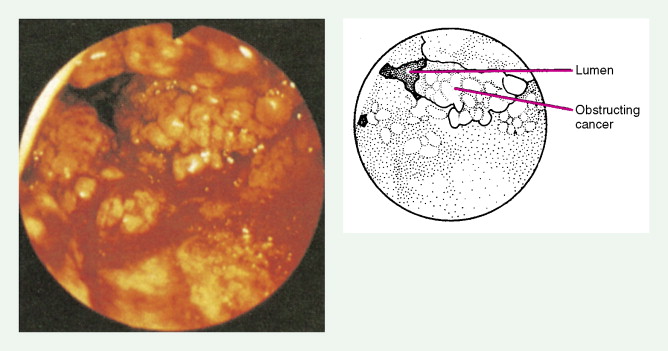

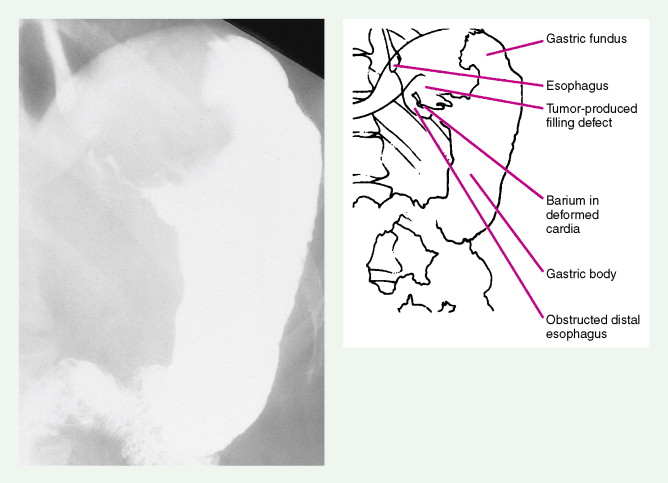

About 90% of patients present with dysphagia and weight loss, often accompanied by pain on swallowing (odynophagia). These symptoms characteristically appear with advanced disease, because difficulty in swallowing arises when at least 60% of the esophageal circumference is infiltrated by cancer. Other symptoms include regurgitation or emesis and discomfort in the throat, substernal area, or epigastrium. In advanced disease, local invasion of the trachea, bronchi, lung, or even aorta may result in aspiration pneumonia, massive hemorrhage, pleural effusion, or superior vena cava syndrome. Moreover, the development of one or more tracheo- or bronchoesophageal fistulae may also occur, as well as esophageal perforation and mediastinitis. Occasionally patients present with supraclavicular lymph node, bone, or liver metastases.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment of esophageal cancers is dependent on the stage of disease as well as whether the health of the patient allows him or her to undergo surgery. For patients with resectable cancers, options would include surgery alone, combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by surgery, or chemoradiation alone. Despite lack of definitive data supporting this approach, for tumors with at least moderate invasion into the esophageal wall and/or regional lymph node involvement, most patients in the United States are treated with chemoradiation followed by surgery. For patients not deemed operative candidates, who refuse surgery, or who have nonresectable disease but lack distant metastases, combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation therapy is the treatment of choice and can lead to a cure in select patients. Finally, patients with metastatic disease should be considered for palliative therapies, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or esophageal stenting.

Gastric Cancers

There is a marked variation in the incidence of gastric cancer worldwide. Death rates are highest in Costa Rica and Japan, about 10-fold greater than those in the United States. Nonetheless, both the incidence and the mortality rate of gastric cancer have decreased worldwide over the past 50 years. In 1930 gastric cancer was the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men, with a rate of 37 per 100,000 in the United States, as compared with the current U.S. rate of less than 6 per 100,000. The incidence of gastric cancer increases after age 50 and is highest in lower socioeconomic groups. The male-to-female ratio of 3:2 is less than observed in esophageal cancer.

Many etiologic influences have been proposed to explain the decreasing incidence of gastric cancer, mostly concerning dietary and environmental factors and the increased availability of refrigeration, which reduces the growth of nitrate-producing bacteria in food. Another factor, loss of gastric acidity, may predispose to stomach cancer. This condition can be caused by partial gastrectomy, atrophic gastritis, or achlorhydria with subsequent pernicious anemia. Chronic gastritis is frequently associated with gastric cancer, and the presence of intestinal metaplasia further elevates the risk of gastric cancer. Recent studies suggest that infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with gastric cancer, leading some to postulate a pathogenic role. Other premalignant lesions include adenomas, 40% of which may progress to carcinoma. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is associated with mutations in the E-cadherin gene.

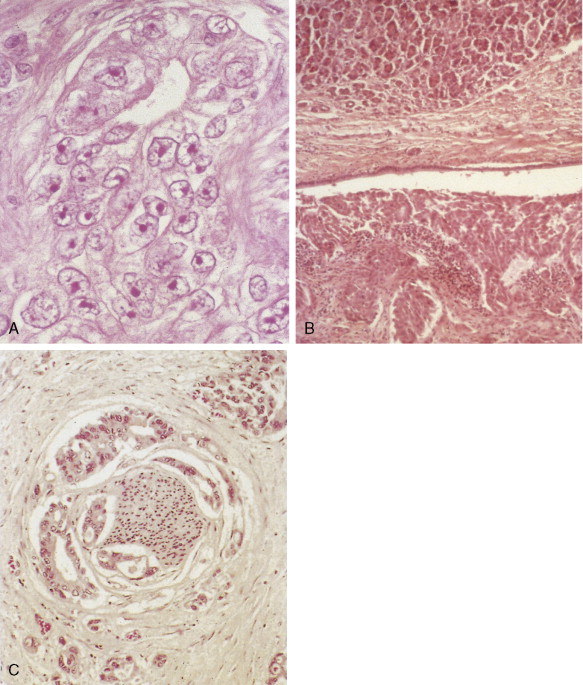

HISTOLOGY

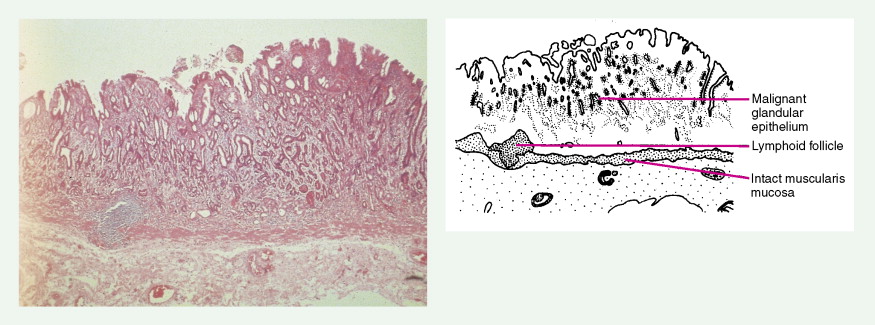

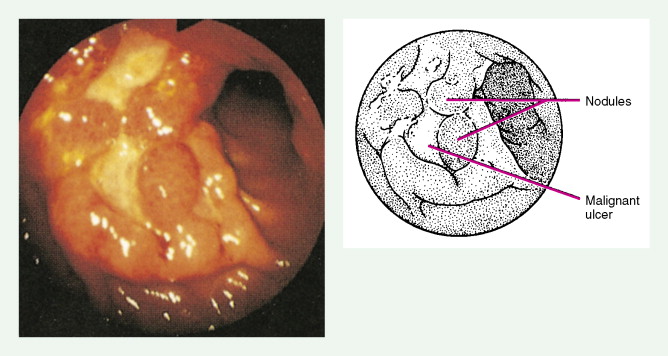

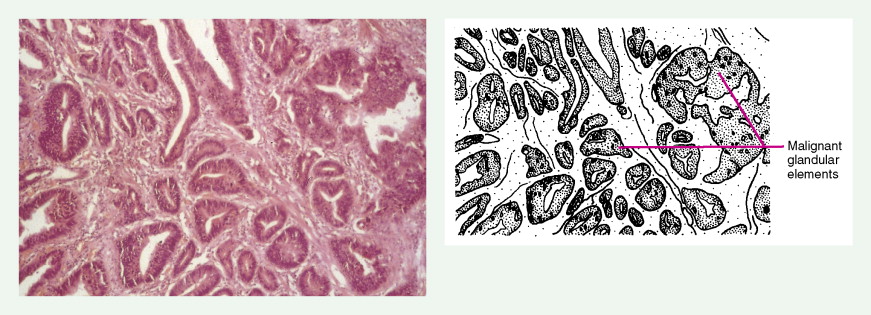

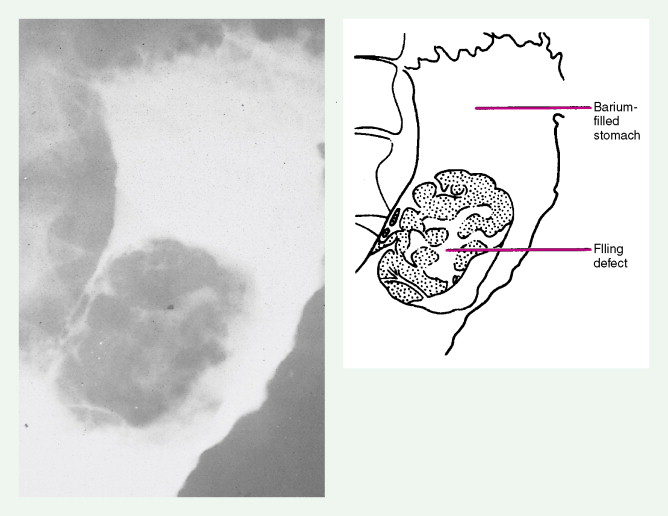

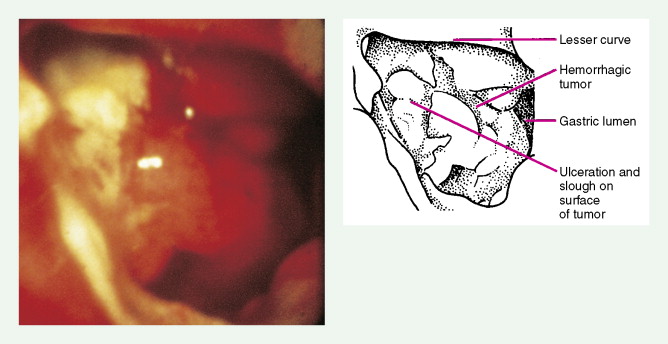

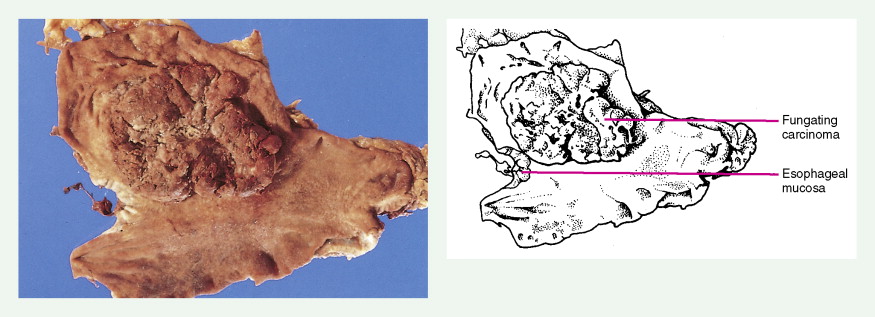

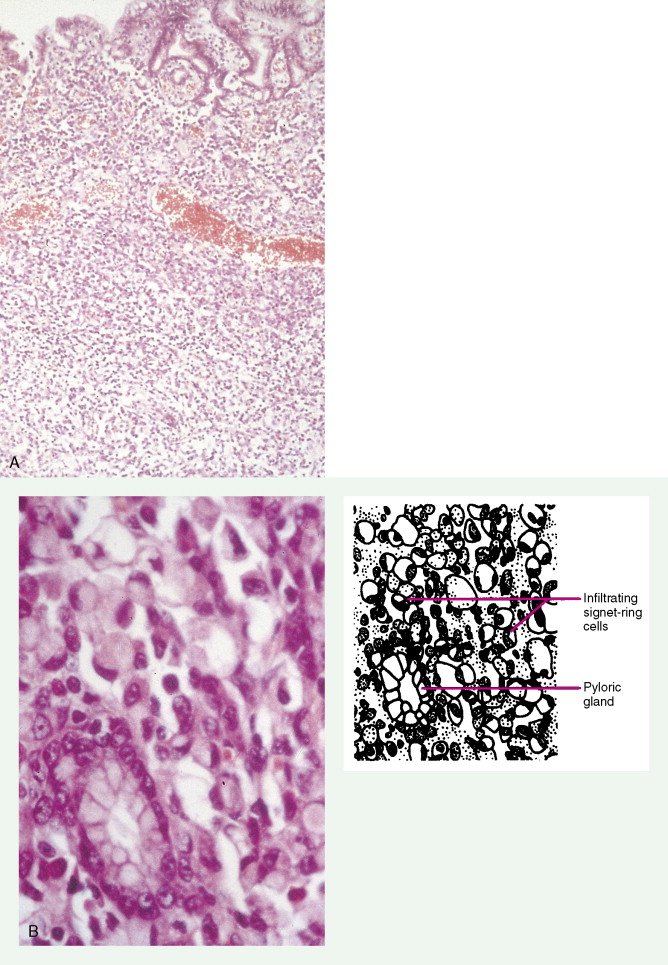

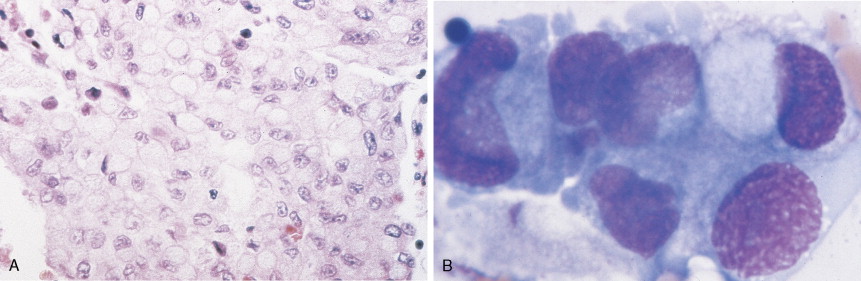

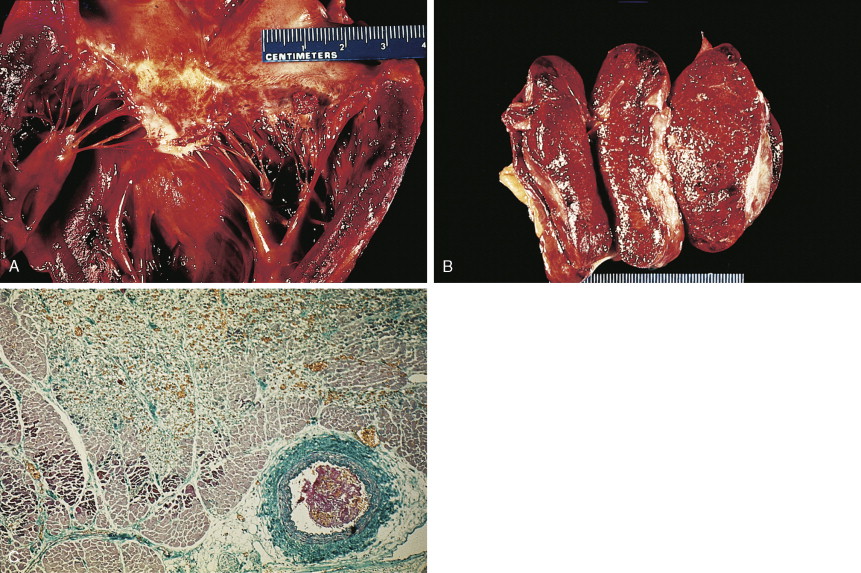

About 90% of gastric malignancies are adenocarcinomas, with the remainder comprising malignant gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumors (GISTs; leiomyosarcomas) and lymphomas. Histologically, adenocarcinomas are classified as intestinal or diffuse. Intestinal-type cancers are characterized by cohesive neoplastic cells that form glandlike tubular structures resembling colonic adenocarcinomas. They are often preceded by premalignant changes (chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia) and may result in ulcerative lesions, particularly in the antrum or the lesser curvature. Diffuse-type cancers are composed of infiltrating gastric mucous or “signet-ring” cells that infrequently form masses or ulcers. They tend to occur throughout the stomach, often resulting in a linitis plastica (“leather bottle”) appearance. Much of the decline in gastric cancer rates has been due to decreases in the intestinal type. Consequently, the diffuse-type adenocarcinomas have become relatively more common, accounting for up to one third of cases. Diffuse-type malignancies are associated with a very poor prognosis, with a survival rate of less than 2%. Much of the pale “tumor” tissue in this variant actually represents fibrosis of the submucosa and muscle.

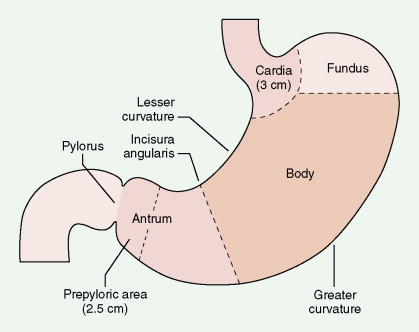

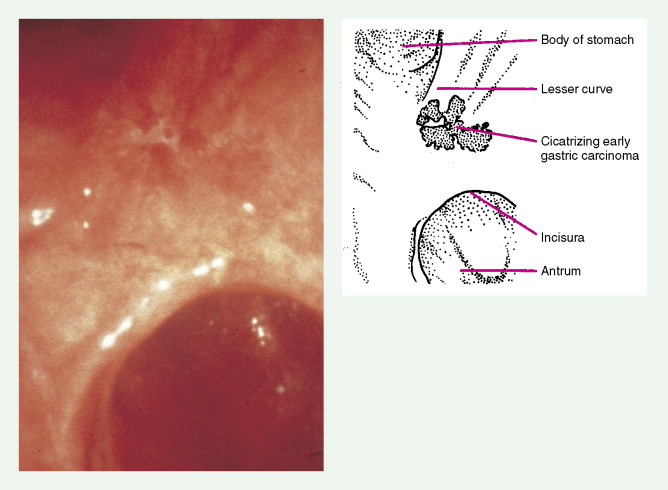

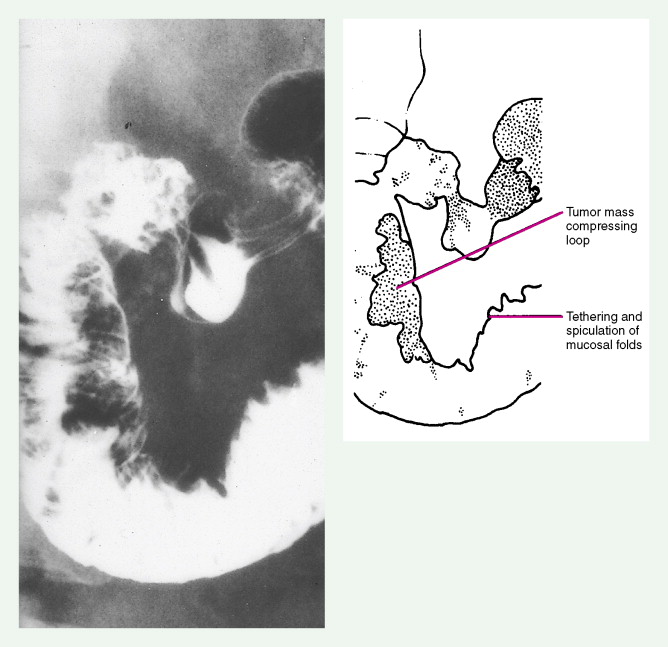

Macroscopically, gastric cancers are classified into five categories. The ulcerative variant (25% of cases) may resemble a benign gastric ulcer. About 7% and 36% are polypoid and fungating tumors, respectively, and are nodular tumors that can reach a large size. The remaining 26% of gastric cancers show a scirrhous pattern caused by thickening and rigidity of the gastric wall due to diffuse infiltration by signet-ring cells. The marked fibrous reaction results in the appearance of linitis plastica. The least common gross appearance is the superficial type, representing less than 6% of cases. The normal mucosa is replaced by sheetlike collections of malignant cells that do not invade beyond the submucosa. This type is categorized as early gastric cancer and represents potentially resectable (for cure) cancers.

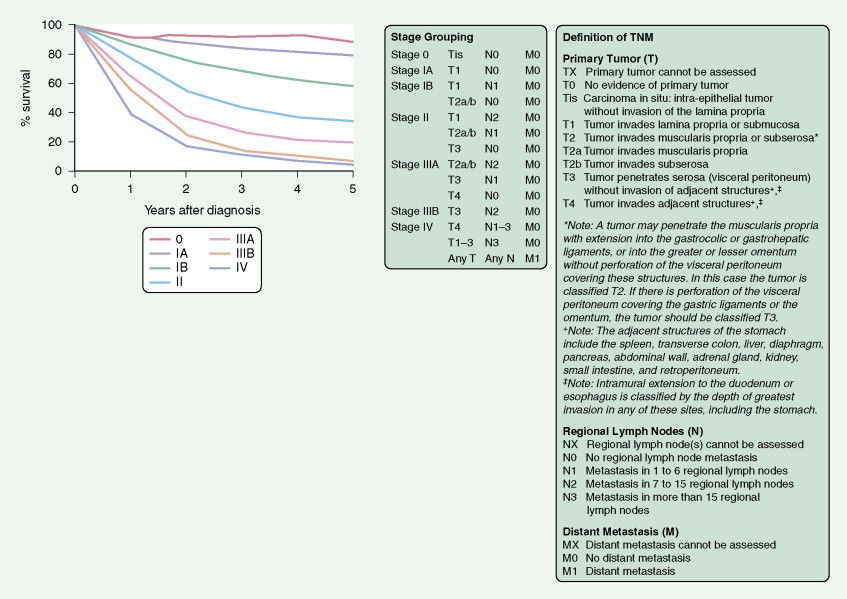

STAGING OF GASTRIC CANCERS

A TNM staging system is used for gastric cancers. Prognosis is dependent both on stage of disease and location within the stomach. Proximal tumors (within the cardia and fundus) have a worse prognosis than distal tumors (antrum and pylorus). The 5-year survival rate is 45% to 80% for the uncommon cases that are detected in stage I of the disease, 25% to 40% for stage II, less than 20% for stage III, and 5% for stage IV.

Extensive local invasion by gastric cancer is common and most often involves the pancreas, omentum, transverse colon, liver, or spleen; direct contiguous spread into the esophagus or duodenum is also common. Moreover, because gastric cancer so often penetrates the serosa, it is particularly prone to transperitoneal dissemination. Spread also occurs via lymphatics and blood vessels. Gastric cancer can lead to drop metastases to the large and small bowel, pelvic floor, and ovary. Staging studies include endoscopy with or without endoscopic ultrasound, chest imaging; CT scans of liver, abdomen, and pelvis should be obtained.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Because early gastric cancer is asymptomatic, many patients present with advanced disease. Symptoms include ulcer-related pain, anorexia, weight loss, and vague epigastric distress. Development of left supraclavicular adenopathy (Virchow’s node), an ovarian mass (Krukenberg tumor), hepatomegaly, ascites, or anemia may be the initial manifestation. Gastric carcinoma is also a well-recognized cause of secondary pyloric stenosis in adulthood.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Up to 50% of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer are considered inoperable, and treatment should be directed toward palliation. Options for palliation include best supportive care only, systemic chemotherapy, radiation therapy (usually limited to control bleeding and obstructive systems), and endoscopic stenting. For patients with resectable disease, growing evidence supports the role of either postoperative adjuvant therapy (with combination of chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy) or neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery followed by further adjuvant chemotherapy.

| Subdivision | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Antrum and prepylorus | ≥50 |

| Cardia and fundus | –25 |

| Lesser curvature | 20 |

| Greater curvature | 3–5 |

| Entire stomach | 5–10 |

Pancreatic Cancers

The increasing incidence of exocrine pancreatic cancers in the United States reflects the aging of the population. About 32,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, with nearly as many deaths. It is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in adults in the United States. The median age of patients with these tumors is approximately 70 years, with one third of cases occurring in persons aged 75 years or older. About one quarter of patients are younger than 60 years. The etiology remains obscure, except for a known association with cigarette smoking; pancreatic cancer is two to four times more common in heavy smokers than in nonsmokers. Other risk factors include diabetes mellitus and rare hereditary syndromes (e.g., ataxia-telangiectasia, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and hereditary chronic pancreatitis). Data are mixed regarding the risk of alcohol abuse and chronic pancreatitis in the development of pancreatic cancer.

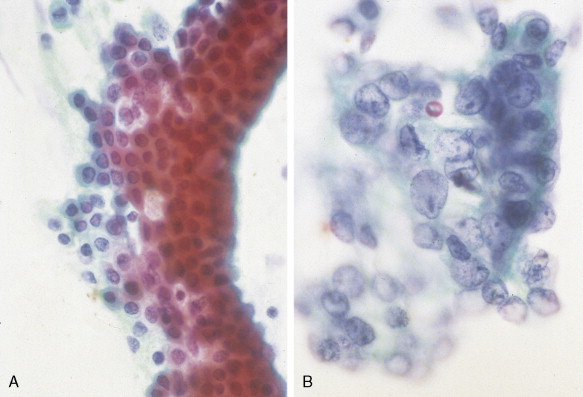

HISTOLOGY

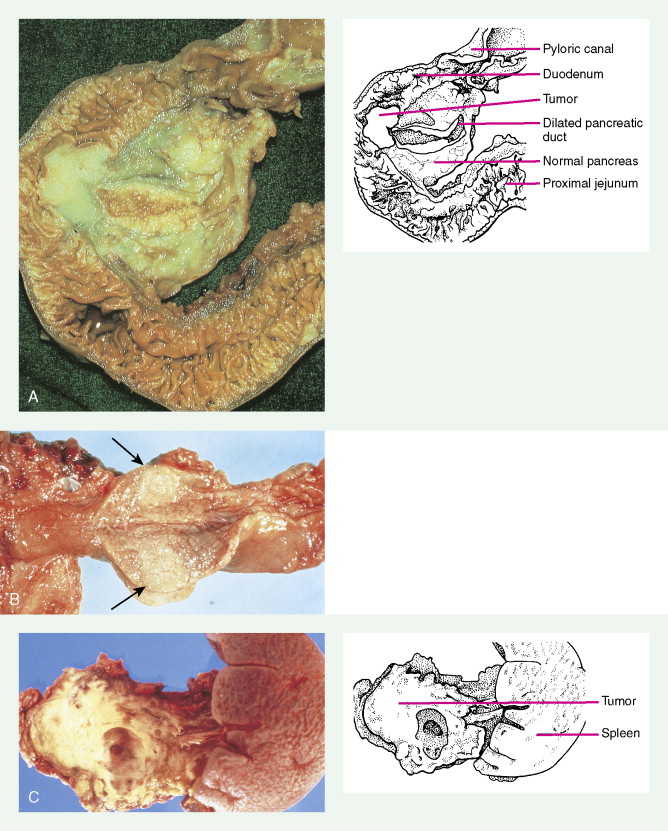

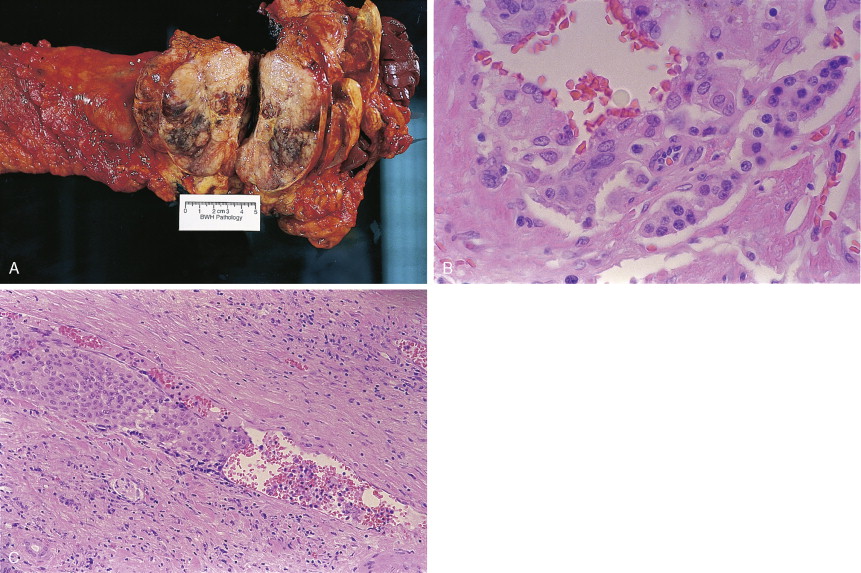

About 75% of pancreatic malignancies are ductal adenocarcinomas, of which approximately 70% occur in the head of the pancreas. A variety of uncommon types of pancreatic carcinoma have been described, including acinar, adenosquamous, anaplastic, papillary, mucous, and microadenocarcinomas, each of which composes less than 5% of the total. All of these have similarly poor prognoses and are treated in a similar fashion. Also uncommon are mucinous cystic neoplasms (cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma) of the pancreas, which occur most frequently in middle-aged women. These are typically located in the tail of the pancreas. Clinical behavior can be difficult to predict pathologically, leading some to conclude that all mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas have malignant potential. Complete surgical resection results in cure rates of 30% to 60%. The remaining 5% to 10% of pancreatic neoplasms are predominantly islet cell–derived (see Chapter 10 ). Other rare neoplasms include pancreatoblastomas, most of which occur in children, and the solid and cystic neoplasms. The latter occurs most frequently in young women and carries an excellent prognosis following resection.

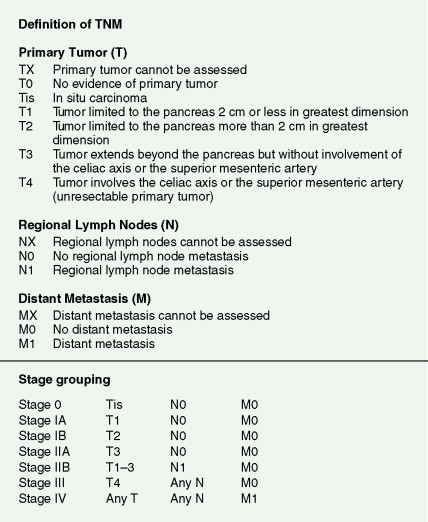

STAGING OF PANCREATIC CANCERS

Pancreatic cancer most commonly presents at an advanced stage. Early or local disease (stage I), with cancer confined to the pancreas, is unusual. Regional disease (stage II or III) is more common and includes tumor invasion into the bile duct, duodenum, adjacent peripancreatic tissue, or adjacent lymph nodes. Extensive disease (stage IV) signifies either invasion of tumor into the stomach, colon, spleen, or blood vessels, or the presence of distant metastases. More practically, pancreatic cancer can be divided into three stages: local/resectable, locally advanced (considered unresectable but without distant metastases), and metastatic. The overall prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma (excluding mucinous cystic neoplasms) is dismal, with a median survival time of 4–6 months and a 5-year survival rate of 2% to 3%.

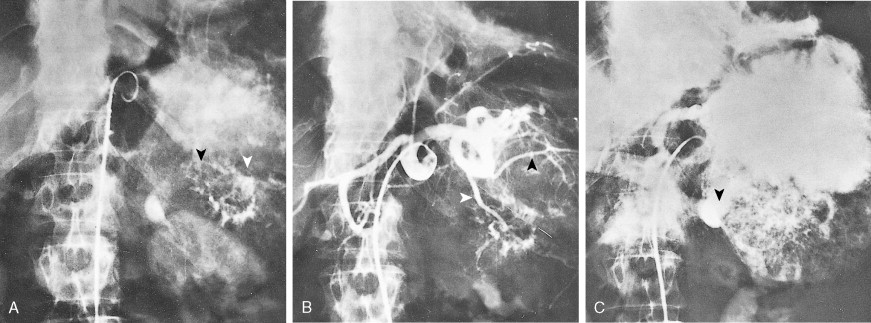

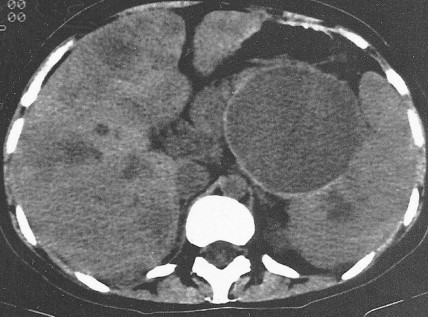

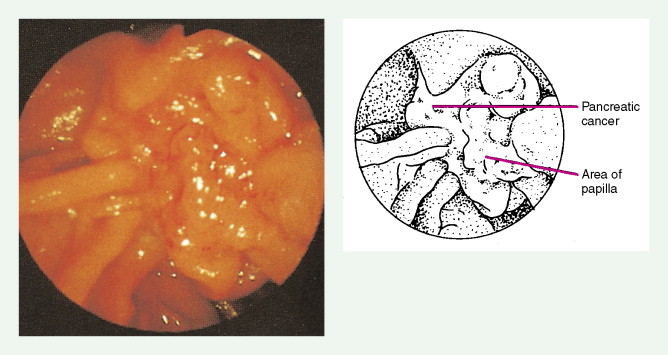

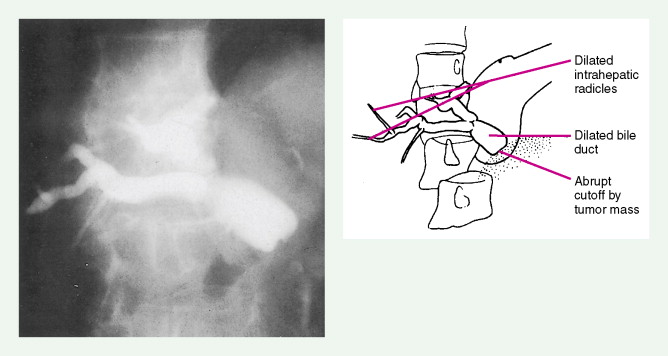

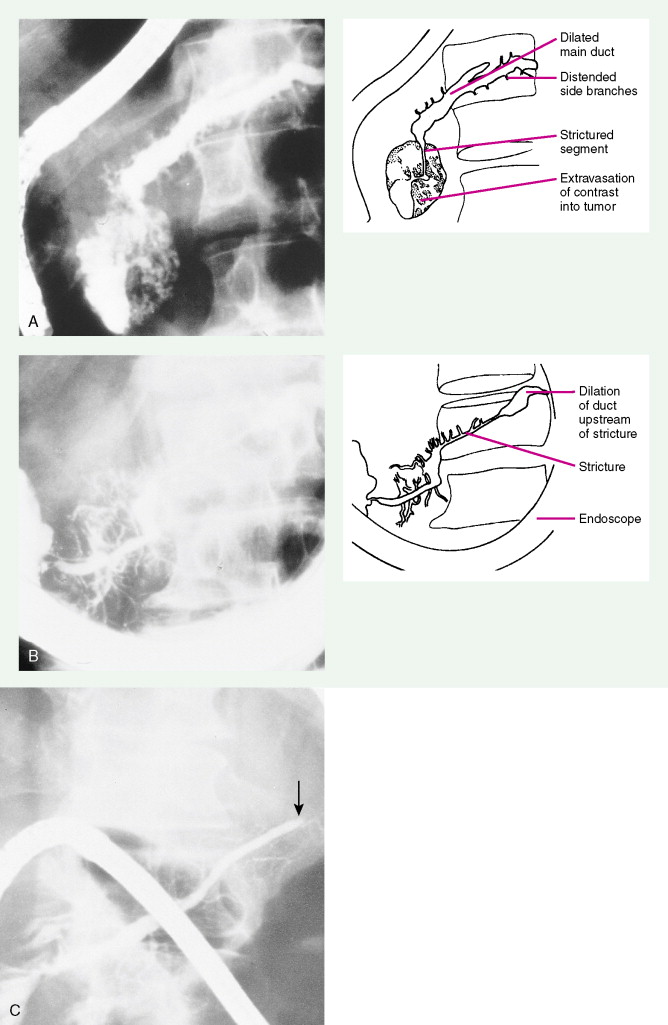

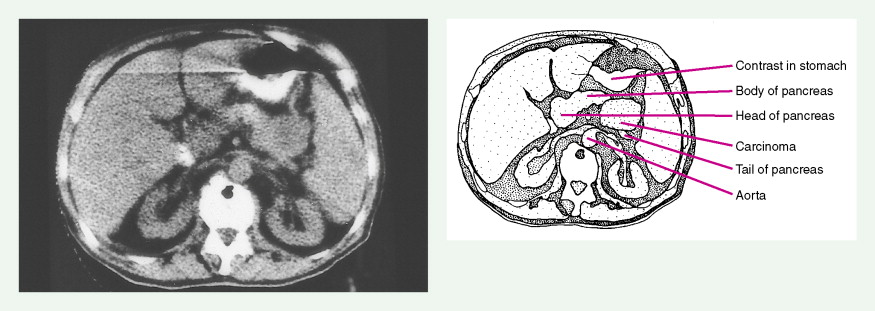

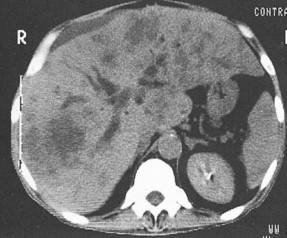

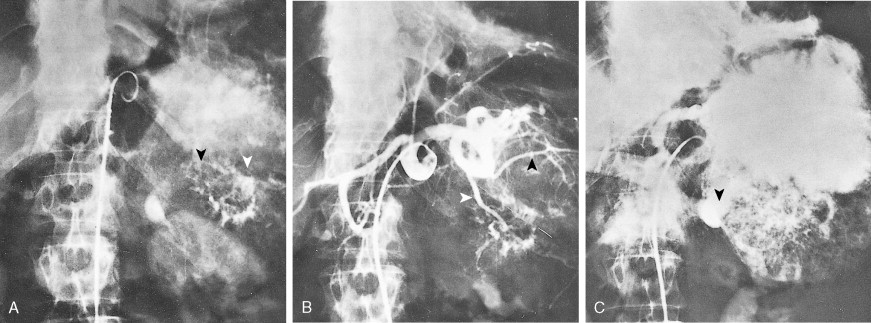

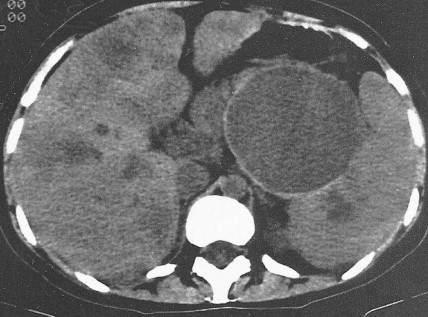

Staging procedures include ultrasonography, CT scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A diagnostic laparoscopy may also be performed to detect peritoneal disease that is not visible radiologically. Regardless of these studies, an accurate histologic diagnosis is necessary to distinguish benign disease from carcinoma, islet cell tumors, and retroperitoneal lymphomas, because of the major therapeutic and prognostic differences among these disease entities. When liver metastases are present, fine-needle aspiration biopsy is often successful in establishing a diagnosis of metastatic disease. In the case of locally advanced disease, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or fine-needle aspiration may be used. In the setting of a resectable pancreatic mass, biopsy may be deferred in favor of proceeding directly with surgical resection. Criteria for surgical resection include absence of metastatic disease and absence of invasion of prominent local blood vessels.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

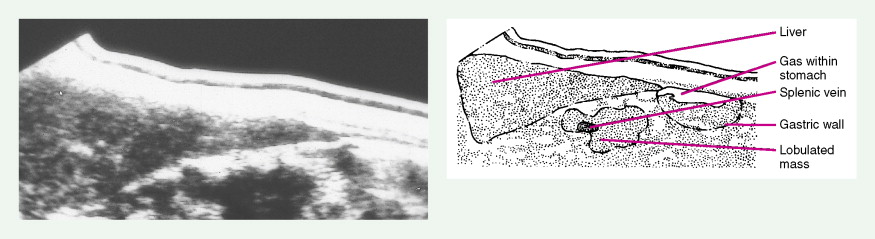

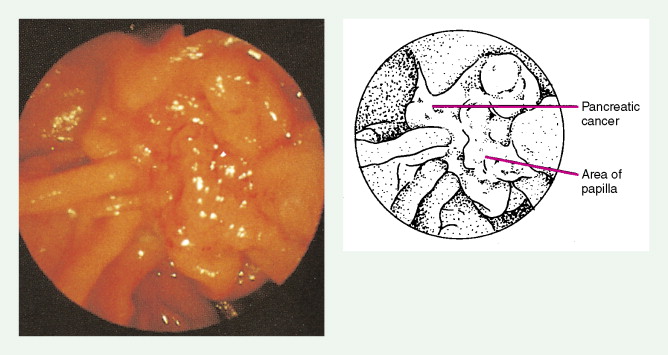

Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas leads to jaundice caused by biliary obstruction. The gallbladder is usually distended (Courvoisier sign). Carcinomas of the body and tail are accompanied by severe pain resulting from retroperitoneal invasion and infiltration of the celiac ganglia and splanchnic nerves. However, body and tail lesions are often detected at later stages because symptoms do not occur until the disease has advanced more than pancreatic head tumors. About 75% of patients present with pain and progressive weight loss. Splenomegaly, due to encasement and obstruction of the splenic vein, may also occur. Other features include depression, diabetes mellitus (5% to 10% of cases), alterations in bowel function (particularly obstipation), and venous thrombosis with migratory thrombophlebitis (Trousseau sign; see “Hepatobiliary Cancers” ).

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment of pancreatic cancer is dependent on the clinical stages described earlier—local/resectable, locally advanced, and metastatic. For resectable disease surgery remains the treatment of choice (although recurrence rates are >80%). The use and choice of adjuvant therapy remain controversial but may include chemotherapy alone or combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For patients with locally advanced disease either chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone should be considered. Patients with metastatic disease should be considered for chemotherapy; however, the benefits for most patients remain limited.

Pancreatic Cancers

The increasing incidence of exocrine pancreatic cancers in the United States reflects the aging of the population. About 32,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, with nearly as many deaths. It is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in adults in the United States. The median age of patients with these tumors is approximately 70 years, with one third of cases occurring in persons aged 75 years or older. About one quarter of patients are younger than 60 years. The etiology remains obscure, except for a known association with cigarette smoking; pancreatic cancer is two to four times more common in heavy smokers than in nonsmokers. Other risk factors include diabetes mellitus and rare hereditary syndromes (e.g., ataxia-telangiectasia, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and hereditary chronic pancreatitis). Data are mixed regarding the risk of alcohol abuse and chronic pancreatitis in the development of pancreatic cancer.

HISTOLOGY

About 75% of pancreatic malignancies are ductal adenocarcinomas, of which approximately 70% occur in the head of the pancreas. A variety of uncommon types of pancreatic carcinoma have been described, including acinar, adenosquamous, anaplastic, papillary, mucous, and microadenocarcinomas, each of which composes less than 5% of the total. All of these have similarly poor prognoses and are treated in a similar fashion. Also uncommon are mucinous cystic neoplasms (cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma) of the pancreas, which occur most frequently in middle-aged women. These are typically located in the tail of the pancreas. Clinical behavior can be difficult to predict pathologically, leading some to conclude that all mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas have malignant potential. Complete surgical resection results in cure rates of 30% to 60%. The remaining 5% to 10% of pancreatic neoplasms are predominantly islet cell–derived (see Chapter 10 ). Other rare neoplasms include pancreatoblastomas, most of which occur in children, and the solid and cystic neoplasms. The latter occurs most frequently in young women and carries an excellent prognosis following resection.

STAGING OF PANCREATIC CANCERS

Pancreatic cancer most commonly presents at an advanced stage. Early or local disease (stage I), with cancer confined to the pancreas, is unusual. Regional disease (stage II or III) is more common and includes tumor invasion into the bile duct, duodenum, adjacent peripancreatic tissue, or adjacent lymph nodes. Extensive disease (stage IV) signifies either invasion of tumor into the stomach, colon, spleen, or blood vessels, or the presence of distant metastases. More practically, pancreatic cancer can be divided into three stages: local/resectable, locally advanced (considered unresectable but without distant metastases), and metastatic. The overall prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma (excluding mucinous cystic neoplasms) is dismal, with a median survival time of 4–6 months and a 5-year survival rate of 2% to 3%.

Staging procedures include ultrasonography, CT scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A diagnostic laparoscopy may also be performed to detect peritoneal disease that is not visible radiologically. Regardless of these studies, an accurate histologic diagnosis is necessary to distinguish benign disease from carcinoma, islet cell tumors, and retroperitoneal lymphomas, because of the major therapeutic and prognostic differences among these disease entities. When liver metastases are present, fine-needle aspiration biopsy is often successful in establishing a diagnosis of metastatic disease. In the case of locally advanced disease, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or fine-needle aspiration may be used. In the setting of a resectable pancreatic mass, biopsy may be deferred in favor of proceeding directly with surgical resection. Criteria for surgical resection include absence of metastatic disease and absence of invasion of prominent local blood vessels.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas leads to jaundice caused by biliary obstruction. The gallbladder is usually distended (Courvoisier sign). Carcinomas of the body and tail are accompanied by severe pain resulting from retroperitoneal invasion and infiltration of the celiac ganglia and splanchnic nerves. However, body and tail lesions are often detected at later stages because symptoms do not occur until the disease has advanced more than pancreatic head tumors. About 75% of patients present with pain and progressive weight loss. Splenomegaly, due to encasement and obstruction of the splenic vein, may also occur. Other features include depression, diabetes mellitus (5% to 10% of cases), alterations in bowel function (particularly obstipation), and venous thrombosis with migratory thrombophlebitis (Trousseau sign; see “Hepatobiliary Cancers” ).

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment of pancreatic cancer is dependent on the clinical stages described earlier—local/resectable, locally advanced, and metastatic. For resectable disease surgery remains the treatment of choice (although recurrence rates are >80%). The use and choice of adjuvant therapy remain controversial but may include chemotherapy alone or combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For patients with locally advanced disease either chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone should be considered. Patients with metastatic disease should be considered for chemotherapy; however, the benefits for most patients remain limited.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree