Abstract

Just as the surgical management of breast cancer has evolved, so too has the field of breast surgery. Patient and surgeon expectations are no longer limited to recreating a breast mound but instead to recreate esthetically pleasing, symmetrical breasts, thus improving quality of life and body image. The number of women undergoing reconstruction continues to increase each year. Breast reconstruction must be accomplished without handicapping any future treatment for the breast cancer and keeping the operation relatively simple, reproducible, and, most important, safe. The surgical changes in the treatment of breast cancer have changed dramatically from the Halsted radical mastectomy to the breast-conserving therapies of today. To perform breast reconstructions or breast reductions, one must know the ideal esthetics of the breasts, the diagnosis, and the surgical reconstructive objectives. This chapter covers breast reconstruction after mastectomies, breast reductions, and oncoplastic breast surgery, an evolving field that combines all available techniques. The surgical description of common reconstructive techniques is described.

Keywords

breast reconstruction, implant reconstruction, flap reconstruction, breast reduction

Just as the surgical management of breast cancer has evolved, so too has the field of breast surgery. Patient and surgeon expectations are no longer limited to recreating a breast mound but instead to recreate esthetically pleasing, symmetrical breasts, thus improving the quality of life and body image. The number of women undergoing reconstruction continues to increase each year. Breast reconstruction must be accomplished without handicapping any future treatment for the breast cancer and keeping the operation relatively simple, reproducible, and, most important, safe. The surgical changes in the treatment of breast cancer have changed dramatically from the Halsted radical mastectomy to the breast-conserving therapies of today. To perform breast reconstructions or breast reductions, one must know the ideal esthetics of the breasts, the diagnosis, and the surgical reconstructive objectives. This chapter covers breast reconstruction after mastectomies, breast reductions, and oncoplastic breast surgery, an evolving field that combines all available techniques. The surgical description of common reconstructive techniques is described.

Role of Reconstruction in Breast Cancer Treatment

Breast reconstruction is performed to correct anatomic abnormalities, and thus it is always a functional procedure. It is expected that any reconstructive breast procedure will improve appearance after mastectomy or radiation injury. After the passage of a 1998 federal law that ensures coverage from insurance providers for breast reconstruction in the setting of breast cancer treatment, the prevalence of reconstruction continues to increase.

Until the late 1970s and early 1980s, breast reconstructions were mostly performed in delayed fashion after mastectomy. At that time, there were a number of concerns about performing immediate breast reconstruction related to the oncologic safety of reconstruction: the possibility of hiding local recurrences, seeding of the breast tumor throughout the chest or donor site, and interference with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Many studies have subsequently been done to address each concern for immediate breast reconstruction. As far as oncologic safety is concerned, most local recurrences occur either in the subcutaneous tissue or along the scar within 3 years after the mastectomy. This is true regardless of whether the patient has undergone breast reconstruction. Multiple studies have confirmed the safety of immediate breast reconstruction, even for patients with advanced disease. Consequently, recurrences are easily detected with palpation or inspection. To address the concerns of seeding the donor site, reconstructive surgeons, in cooperation with oncologic surgeons, have adopted two separate surgical fields including all instruments. One study demonstrated that the majority of the patients who underwent immediate reconstruction were able to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy within 6 weeks of mastectomy and reconstruction. A significant percentage of patients who underwent mastectomy without reconstruction had the institution of adjuvant chemotherapy delayed beyond 6 weeks as a result of the persistence of seromas along the axilla or chest skin flap necrosis. The overall complication rates for these two groups of patients were also identical (18%).

Several determining factors are reviewed with the patient before deciding on the type of breast reconstruction. Each of the techniques described in this chapter has advantages and disadvantages. Factors include the type of mastectomy (i.e., nipple- and skin-sparing technique vs. standard modified radical mastectomy), body habitus, opposite breast size and shape, previous abdominal surgery, history of smoking, and of course the overall health of the patient. Equally important is a comprehensive understanding of breast cancer. Patients expected to receive postoperative radiation will have irreversible changes to the chest wall tissues that inevitably alter the final cosmetic result. A discussion with the patient regarding the expected outcomes needs to occur, and in selected cases, delaying the reconstruction process may be the best option for those who want the best result. Finally, the wishes and desire of the patient are considered when determining the best reconstructive plan. The decision of breast reconstruction should involve a multidisciplinary team coordinated with all of the treating specialties.

The reconstructive breast surgeon should be familiar and proficient at performing all reconstructive options. Each patient has her specific goals and challenges, and thus there is no standardized procedure that fits all breast reconstructions. Preoperative evaluation and counseling on the reconstruction options and expectations are critical to achieve the desired results.

Definition of the Mastectomy Deformity

Mastectomy

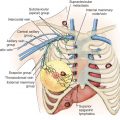

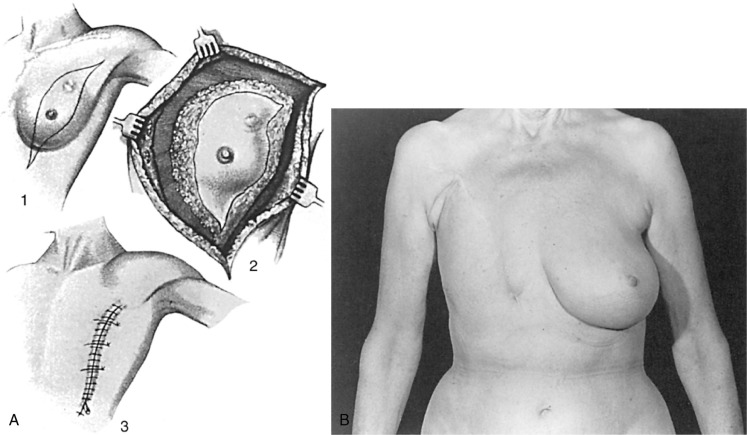

From the standpoint of the reconstructive surgeon, the ideal total mastectomy should preserve the pectoralis major muscle and skin that is not essential to the tumor resection. When this approach is used, the functional considerations of mobility of the shoulder and soft tissue coverage of the ribs are achieved ( Fig. 33.1 ). Extensive skin excision, which results in a tight skin closure, has not been shown to enhance survival, but it does make reconstruction much more difficult. Autogenous flaps are needed after mastectomies with a radical skin excision.

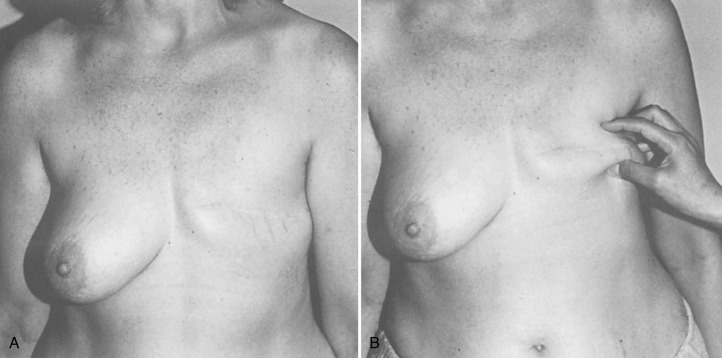

The placement of the incision for a non–nipple- or skin-sparing mastectomy is an important factor that determines the overall outcome. In this regard, the foremost consideration is to place the incision in the appropriate lines of skin tension. It is easy to identify the exact direction of the skin tension lines by pinching the skin to accentuate the wrinkles. Rather than using the standard transverse ellipse, an incision is chosen in the lower or lateral breast, which provides adequate access for any mastectomy. A low and oblique closure is preferred because it is better hidden and offers much better shoulder and chest mobility than a higher incision. The worst choice for a closure in a patient who will eventually have a breast reconstruction is the transverse Patey incision. It is inelastic and unexpandable and results in the least attractive scars ( Fig. 33.2 ). Large-breasted women with grade II to III ptosis can have the skin flap size reduced with a Wise-pattern reduction technique, described later in this chapter. With the continued increase in nipple-sparing mastectomy, several studies have been published regarding the ideal incision location. The two commonly advocated locations are the inferolateral inframammary incision and the vertical infraareolar incision. The decision for the location of the incision for nipple-sparing mastectomy procedures should be based on the oncologic surgeon’s ability to safely perform the mastectomy and the reconstructive surgeon’s experience.

Partial Mastectomy/Lumpectomy

The biggest advantage of breast conservation is the preservation of breast sensation. Even though some reconstructed breasts may look as good as natural breasts, we currently do not have reconstruction techniques that can restore nipple sensation. When a complete mastectomy is not performed, the residual defect resulting from the partial mastectomy or lumpectomy can be addressed by several methods. This has created the term oncoplastic breast surgery . With this procedure, different pedicles of breast tissue can be elevated to recontour the breast. Various techniques to reconstruct the breast using reduction mammaplasty techniques have been described in the patient undergoing breast conservation therapy and radiation. Larger defects can be filled with autogenous flaps, with or without skin to allow for a natural shape. The favorable nature of the partial mastectomy defect is the reason that a central tumor should never be the sole justification for choosing a complete mastectomy instead of lumpectomy and radiation. When the lumpectomy deforms the breast, and even when it is necessary to remove the nipple, conservation therapy is still a good option.

Reconstructive Surgical Methods

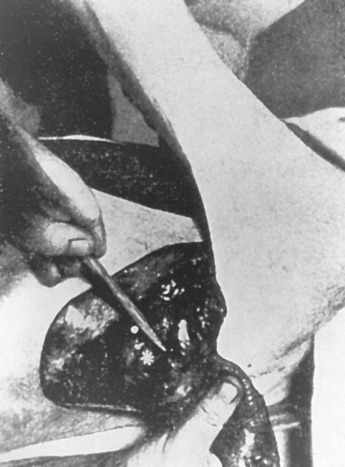

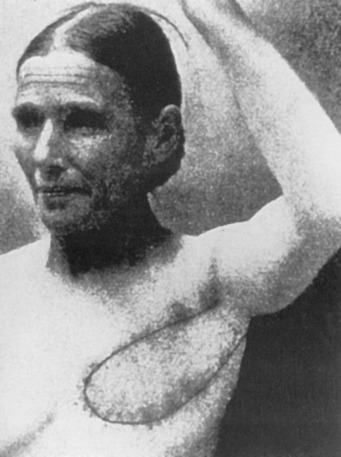

Early on, radical mastectomy was the only treatment for breast cancer. Wide and extreme resections of the breast and skin were performed and allowed to heal in by granulation. This changed after World War II with the greater use on sheet skin grafting, developed in the 1920s. Sheet skin grafting was only used in major centers until the development of the Brown dermatome in the 1950s. By the 1960s, extensive skin flap elevation and primary closure were accepted as safe, having been introduced 20 years earlier. Tube skin grafts were initially used for the most widely accepted tissue reconstruction ( Figs. 33.3–33.6 ) but were arduous and impractical for chest wall reconstruction. Tansini used a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap in the early 1900s ( Fig. 33.7 ) primarily for wound closure ( Figs. 33.8–33.10 ), and the technique is basically how it is performed today. The slow implementation of the latissimus flap was due in part to the opposition of stalwarts like Halsted who did not think it was safe. Tissue reconstruction of chest wall defects after mastectomy became more widely used by the 1970s and in the 1980s when Hartrampf introduced the pedicled abdominal flap.

Early breast implants were made of polyurethane foam, paraffin, or allogenic implants. To avoid some of the severe complications that were reported, silicone gel implants were introduced and popularized by Cronin and Gerow.

Tissue Expansion/Implants

The initial experience with prepectoral placement of implants was complicated by capsular fibrosis and capsule formation, erosion of skin, and distortion of the shape of the reconstructed breast. To solve this problem, tissue expanders were introduced in the early 1980s. Expanders allowed extension of the skin as well as the underlying muscle, and implant reconstruction gained acceptance with this advance. After the wound heals, gradual expansion allows for formation of an appropriate size pocket for an implant. With the wide use of skin- and nipple-sparing techniques, expansion of the submuscular pocket is still necessary, even though the skin does not need expansion. The expander fills the void of the extirpated breast so that the overlying spared skin does not wrinkle. Full tissue coverage requires long surgical times. Pectoralis coverage with partial sling matrix coverage is expensive but requires less operative time. Explantation rates are generally low and secondary to infection and, more rarely, pain. If expanded too quickly, necrosis of the overlying skin or disruption of the suture line can occur. Despite a complication rate of up to 30%, selected groups have learned to do this well, with acceptable complication rates. With the advent of tissue matrix to cover the implant, the patient can undergo direct-to-implant placement. Although useful for the avid athlete, the cosmetic result of direct to implant is estimated to be 90% of the submuscular implant because tension on the skin has to be limited. For the right patient, cosmesis can be excellent.

Reconstruction With Acellular Dermal Matrix

In the past, reconstruction with implants placed subcutaneously resulted in numerous complications. The technique evolved to a subpectoral muscle placement with elevation of the serratus muscle or just its fascia to cover the lower and lateral aspect of the submuscular pocket. The concept changed with the introduction of acellular dermal matrix (ADM), used as an inferior sling to cover the lower pole of the implant. The ease of use and availability of ADM makes it an attractive adjunct to this method of reconstruction, where most of the current reconstructions are subpectoral and sub-ADM over the lower portion of the implant.

The use of ADM has generated its own problems, including prolonged seroma, infection, and increased cost. A modification to the technique is reconstruction with an implant covered circumferentially with ADM and placed in the subcutaneous position.

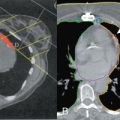

Surgical Technique for Tissue Expander/Acellular Dermal Matrix

The patient is prepped with new drapes after completion of the mastectomy. The arms have been secured in an extended position, allowing for the patient to be placed in the sitting position during the procedure. The mastectomy skin flaps are assessed for perfusion, and hemostasis is obtained. The pectoralis major muscle is elevated from the lateral border, releasing the inferior attachments from the chest wall up to the sternal attachments. A tissue expander is chosen based on the chest diameter. The lateral border is marked extending over the serratus muscle in accordance with the diameter of the expander. A piece of ADM is then sutured to the inframammary fold medially and to the chest wall laterally following the curvature of the chest. Once the ADM is secured, the tissue expander is placed in the subpectoral/sub-ADM pocket. The pectoralis is then sutured over the superior portion of the ADM. The expander can be inflated to a point where no tension has been placed on the skin. With nipple-sparing mastectomies, greater expansion allows for more appropriate placement of the nipple, which aids in the postexpansion position. Two drains are placed exiting the pocket in the inferolateral position. The skin edges are trimmed because of the trauma of retraction during the case. A three-layered closure is performed ( Figs. 33.11–33.13 ).

Myocutaneous Flaps

Subpectoral implants are useful when most of the skin of the breast can be saved. However, in the face of the removal of large amounts of skin as in the modified radical mastectomy and radical mastectomy, muscle and skin coverage is needed.

Surgical Technique of the Latissimus Flap

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction was reintroduced in the 1970s. Latissimus reconstruction allows for replacement of the shape of the pectoralis muscle and breast and skin. However, the latissimus does not have enough volume to be used by itself for a full breast. Use with an underlying implant was initially good but deteriorated over time. Nevertheless, the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap gave the first acceptable results with breast reconstruction after radical mastectomy.

The patient should be marked preoperatively in an upright standing position. The transverse skin island to be used should be no wider than 6 cm and should be fashioned at the approximate level of the bra strap. Depending on the preference of the operating team, the plastic surgeon can harvest the latissimus in the lateral decubitus position, and the flap can be placed in the axilla and closed. The patient can then be repositioned supinely, and oncologic team removes the breast. This minimizes the amount of patient turning on the operating table. Alternatively, the mastectomy can proceed first with subsequent harvest of the latissimus. When axillary node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy is to be performed, care should be taken by the oncologic team not to damage the blood supply to the flap, the thoracodorsal vessels. After dividing the peripheral origin of the muscle, the skin and underlying muscle are rotated into the breast pocket through a subcutaneous tunnel and sutured to the anterior chest wall. This creates the pocket for an implant. Together with the muscle and subcutaneous fat, the transfer creates the new breast mound. The autogenous latissimus dorsi flap is also the procedure of choice for partial mastectomy defects rather than the more complex TRAM flap. If less than 50% of the breast volume is removed, the autogenous latissimus flap can result in perfect correction for lumpectomy-irradiation failures that require mastectomy.

Irradiated skin is best excised if damage is considerable and should be avoided in areas of skin with telangiectasia, dermal and subcutaneous atrophy, edema, and, in some cases, subcutaneous fibrosis to avoid postoperative skin necrosis, implant extrusion, and wound infection or disruption. At a minimum, the skin flap should be elevated and, if possible, at the submuscular plane. If an implant is used, it must be covered in its entirety with muscle because if the irradiated skin disrupts, the implant will be protected by the muscle layer. There is a greater chance for more severe capsular contracture in postirradiated patients, but the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap itself is quite safe and can even be used to cover radiation-exposed implants ( Figs. 33.14–33.19 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree