Breast Cancer in Younger Women

Ann H. Partridge

Aron Goldhirsch

Shari Gelber

Richard D. Gelber

OVERVIEW

Breast cancer rarely occurs in young women. Of the hundreds of thousands of breast cancers diagnosed worldwide, fewer than 0.1% occur in women under age 20 years; 1.9% between ages 20 and 34; and 10.6% between ages 35 and 44 (1, 2). Although fewer than 7% of women diagnosed with breast cancer are younger than age 40, more than 13,000 young women are diagnosed annually with invasive or noninvasive breast cancer in the United States alone, with thousands more diagnosed worldwide (3). Incidence rates in young women appear to be fairly stable over the past several decades in young women in the Western world, despite increases in mammography and reproductive and lifestyle trends (4). A suggestion is that rates are increasing among young women, particularly in less-developed countries, but this may be owing to improvements in awareness, diagnosis, and reporting (5, 6).

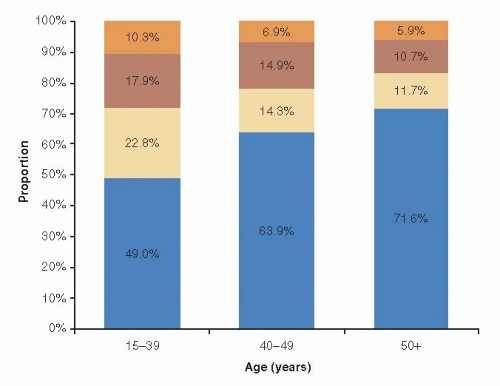

Despite the relative rarity of breast cancer in young women, it is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women under age 40, and survival rates for young women with breast cancer are lower than for their older counterparts. The 5-year relative survival rate for women with breast cancer diagnosed before age 40 is 84% compared with 90% for women diagnosed at age 40 or older (3). The preponderance of evidence to date suggests that young age is an independent risk factor for disease recurrence and death, despite young women having conventionally received more intensive treatment than older women (7, 8). Delays in diagnosis and the lack of effective screening in younger women may contribute to the poorer prognosis because they are more likely to present with larger tumors and more involved lymph nodes (9, 10). However, survival differences also likely reflect biological differences in the type of breast cancer identified in young women. Young women are more likely to develop more aggressive subtypes of breast cancer with unfavorable prognostic features, and are less responsive to conventional therapy compared with disease arising in older premenopausal or postmenopausal women (11, 12). Specifically, tumors in young women are more likely to be high-grade, hormone receptor (HR)-negative, and have high proliferation fraction and more lymphovascular invasion. Accumulating evidence suggests that young women are also more likely to develop more aggressive tumor molecular subtypes including greater proportion of triple negative and ERBB2 (formerly HER-2/neu) overexpressing tumors (13, 14) (Fig. 85-1). Furthermore, studies suggest that the prognostic effect of age may vary by tumor phenotype, although additional research is clearly warranted (15, 16).

Recent studies have sought to determine whether breast cancer arising in young women may represent a distinct biologic entity with unique patterns of gene expression and deregulated signaling pathways that may affect prognosis (17, 18 and 19). However, at the present time, it is uncertain whether young age will remain an independent prognostic factor as we continue to elucidate further the distinct molecular biologic features of breast cancers arising in both young and older women.

Also, evidence suggests that biologic subtypes of breast cancer vary by race as a function of age (14, 20). In a large, population-based study of breast cancer subtypes within age and racial subsets, the basal-like breast cancer subtype (ER-, PR-, ERBB2-, cytokeratin 5/6 positive, and/or ERBB1+) was more prevalent among premenopausal black women (39%) compared with postmenopausal black women (14%) and

nonblack women (16%) of any age (p < .001), whereas the better prognosis luminal A subtype (ER+ and/or PR+, ERBB2-) was less prevalent (36% vs. 59% and 54%, respectively). This higher prevalence of basal-like breast tumors and lower prevalence of luminal A tumors likely contributes to the poorer prognoses of young black women with breast cancer (20) (see Chapter 31, Prognostic and Predictive Factors: Molecular).

nonblack women (16%) of any age (p < .001), whereas the better prognosis luminal A subtype (ER+ and/or PR+, ERBB2-) was less prevalent (36% vs. 59% and 54%, respectively). This higher prevalence of basal-like breast tumors and lower prevalence of luminal A tumors likely contributes to the poorer prognoses of young black women with breast cancer (20) (see Chapter 31, Prognostic and Predictive Factors: Molecular).

In addition to being at higher risk of dying from breast cancer, despite conventionally receiving more aggressive therapy, young women face a variety of problems unique to, or accentuated by, their young age. They are more likely to be diagnosed at a life stage when role functioning in the home and work can be threatened or disrupted by the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Issues such as attractiveness and fertility may be of substantial importance. Young women are more likely to have young children for whom they are responsible, or desire to have biologic children following treatment. They also have an increased risk of harboring a genetic risk factor for breast cancer, and often suffer from a relative lack of information regarding treatment and survivorship issues compared with older patients. These concerns may contribute to the greater psychosocial distress seen in younger women at both diagnosis and in follow-up (21).

Research to date on breast cancer in young women is limited by generally small sample sizes and heterogeneous cutoffs used to differentiate between young and old. Although, age is a continuum and any cut-off is somewhat arbitrary. Many investigators have chosen up to age 35 or 40 to define breast cancer in younger women, recognizing that previous work focusing on premenopausal women is composed primarily of women in their 40s, owing to the higher incidence of the disease in older premenopausal women.

RISK FACTORS FOR EARLY-ONSET BREAST CANCER AND GENETICS ISSUES

Aside from female gender, increasing age is the strongest risk factor for developing breast cancer. Consequently, younger women are at much lower risk even when compared with older premenopausal women. An average woman has a 1 in approximately 1,800 risk of developing breast cancer in her 20s, 1 in 230 in her 30s, and 1 in 70 in her 40s (3). Family history is the primary risk factor for developing breast cancer at a young age, particularly when breast cancer has occurred in a first-degree relative at a young age. Although 5% to 10% of breast cancers are attributable to germline mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 on chromosomes 17 and 13, respectively, another 15% to 20% of breast cancers are associated with the presence of gene polymorphisms and environmental factors (e.g., radiation; see later). By virtue of her age alone, a young woman diagnosed with breast cancer has a greater probability of carrying a BRCA mutation. In an unselected group of women under age 40 having surgery for early breast cancer, 9% harbored a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation (22). Other factors, including a personal or family history of ovarian cancer, bilateral breast cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, may increase that risk. The meaning of an unknown variant of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes may also vary by race (23). Young women with breast cancer should consider genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2, particularly if they have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Please see Chapters 17 and 18 for more details.

Some rare genetic disorders may predispose younger women to develop breast cancer. These include Cowden disease (PTEN gene mutation on chromosome 10 and associated with hamartomas, as well as with breast or thyroid cancer at a young age), and Li-Fraumeni syndrome (mutation of TP53 gene on chromosome 17, with increased incidence of soft tissue and bone sarcomas, brain tumors, adrenocortical tumors, and breast cancers) (24) (see Chapter 17 for more detail). Young women exposed to ionizing radiation during childhood and the teenage years, such as survivors of pediatric Hodgkin disease treated with mantle field irradiation, are also at high risk of developing breast cancer (25). Despite preconceptions, most cases of breast cancers occurring in young women appear to be spontaneous and not clearly related to either carcinogens in the environment or family cancer syndromes (26). However, environmental and hormonal risk factors for breast cancer are not well characterized for younger women, but appear to be somewhat different than for older women. Although breastfeeding appears to be protective against breast cancer at any age,

pregnancy appears to have a dual effect on the risk of breast cancer. Large epidemiologic studies indicate that earlier age at first live birth has a long-term protective effect on the lifetime risk of breast cancer, yet it transiently increases the risk immediately following childbirth for 3 to 15 years postpartum (27, 28 and 29). The excess transient early risk of breast cancer is most pronounced among women who are older at the time of their first delivery. Thus, pregnancy has a protective effect for postmenopausal breast cancer and is a risk factor for premenopausal breast cancer, particularly for older premenopausal women. The biologic mechanism for this is not well elucidated. Also contrary to what has been demonstrated in older women, weight gain and higher body mass index appear to be protective against the development of breast cancer at a younger age (30, 31 and 32).

pregnancy appears to have a dual effect on the risk of breast cancer. Large epidemiologic studies indicate that earlier age at first live birth has a long-term protective effect on the lifetime risk of breast cancer, yet it transiently increases the risk immediately following childbirth for 3 to 15 years postpartum (27, 28 and 29). The excess transient early risk of breast cancer is most pronounced among women who are older at the time of their first delivery. Thus, pregnancy has a protective effect for postmenopausal breast cancer and is a risk factor for premenopausal breast cancer, particularly for older premenopausal women. The biologic mechanism for this is not well elucidated. Also contrary to what has been demonstrated in older women, weight gain and higher body mass index appear to be protective against the development of breast cancer at a younger age (30, 31 and 32).

BREAST DIAGNOSTIC ISSUES FOR YOUNG WOMEN

Most lesions arising in the breasts of young premenopausal women will be benign (see Chapter 10, Benign Breast Disease). Mammography is often of limited value in this population because of high breast tissue density, and targeted ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging can provide additional discriminatory information in the workup of a breast abnormality (33, 34). Breast cancers may be more extensive in younger patients, although it is not clear whether they are at higher risk of multicentricity or bilateral disease, in the absence of a hereditary predisposition, and no evidence indicates that multifocality affects survival in this population (35, 36).

TREATMENT ISSUES

Many clinical trials have divided patient populations based on menopausal status, or age greater or less than 50. Virtually no published clinical trials have focused on treatment issues for the youngest women. Trials reporting results of treatments for premenopausal women largely reflect outcomes for patients in their 40s. Thus, findings from studies that consider average results for premenopausal women may not be directly applicable to very young patients.

Local Therapy Issues

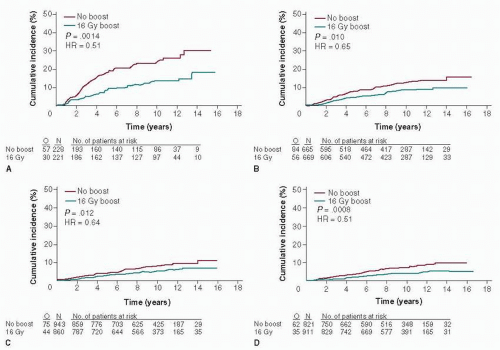

Partly owing to inadequate screening options for young women, breast cancer in young patients tends to be diagnosed at a more advanced stage, with more stage 2 and 3 disease diagnosed than in older women (9, 12). Consequently, young women may more likely need or benefit from preoperative systemic therapy than older women, although available data in this area are limited (37). Despite the large benefit that young women obtain from an irradiation boost to the tumor bed, most studies continue to indicate that young age is a risk factor for local recurrence, for both invasive and noninvasive disease (38, 39 and 40) (Fig. 85-2). No evidence suggests, however, that mastectomy in young women improves survival compared with breast conservation, likely because these women are also at increased risk of systemic recurrence (41, 42). In a population-based Danish cohort of 9,285 premenopausal women with breast cancer, the incidence of local recurrence was 15.4% after breast-conserving therapy among the 719 women under age 35 compared with 3.0% in women ages 45 to 49, although no difference was found in the risk of death between the two age groups (42). Thus, young age alone is not a contraindication to breast conservation. Nonetheless, an increasing number of young women are opting not only for mastectomy, but for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (43). Reasons for this trend are not completely clear, nor is there evidence that such aggressive surgical measures will improve outcomes. For some young women, local therapy decisions may be influenced by the presence or absence of a known genetic risk for new primary breast cancer (i.e., a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation). Thus, prompt genetic counseling and testing for young women at risk for harboring a deleterious genetic mutation should be considered, especially for women for whom the results would have an impact on local therapy decisions. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy are increasingly considered for young women with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, despite the current lack of clear benefits of such risk-reducing strategies in breast cancer survivors (44, 45).

At present, no relevant data are available on the late effects of radiation therapy plus modern systemic therapy (including anthracyclines, taxanes, and trastuzumab) on cardiac functioning in young women. Moreover, other effects of radiation therapy in patients with very long life expectancy must be taken into account (46).

Attention to margin status may be particularly important for young women undergoing breast conservation treatment. In one evaluation including 37 women younger than age 35 with lymph node-negative breast cancer having breast-conserving therapy, local recurrence rates were 50.0% for women with positive margins compared with 20.8% for those with negative margins (47). In a more recent publication, women age 40 or younger with invasive disease had 10-year local recurrence-free survival of 84.4% with negative margins versus 34.6% with positive margins, whereas women over age 40 had local recurrence-free survival of 94.7% if margins were negative compared with 92.6% if margins were positive (48). These findings translated to a 10-year distant disease-free survival (DFS) of 72.0% for younger women with negative margins compared with 39.7% (relative risk [RR] = 3.4) for the younger age group with positive margins, whereas for older women, no significant difference was seen in DFS among those with negative compared to positive margins. There is also evidence that young women may benefit additionally from postmastectomy breast irradiation in the setting of one to three positive axillary lymph nodes (49). Despite the clear benefits, recent population-based data suggest that very young women may be less likely to receive adjuvant breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery (50). Further research is needed to understand these trends.

Systemic Therapy Issues

Adjuvant treatment recommendations are based on tumor and patient characteristics predicting the risk of systemic recurrence and potential responsiveness to therapy, as well as the patient’s preferences and values. Increasingly, treatments are tailored, regardless of age, to the phenotypic subtype of the tumor as assessed by conventional factors, such as grade, proliferation rate, estrogen and progesterone receptors, and ERBB2 expression. More recent application of genetic signature technology has provided additional predictive information regarding the degree of risk and responsiveness to therapy (see Chapter 31). However, most of the data on adjuvant treatment response was obtained during an era when details related to endocrine responsiveness were either incomplete or imprecise. Even today, endocrine responsiveness evaluation requires improved reporting of steroid hormone receptors and a better understanding of the role of ERBB2 overexpression and amplification (51). Currently it is recommended that the estimation of

endocrine responsiveness should be the first consideration in tailoring adjuvant therapies for patients with breast cancer, regardless of age (52). Adjuvant chemotherapy has historically been used extensively in premenopausal patients because of its overwhelming beneficial effects on outcome (53). The incremental benefits of newer cytotoxic drugs and regimens, including the addition of the taxanes, dose density, and trastuzumab, appear to be present across age groups, although data for very young women are limited (54, 55, 56, 57 and 58).

endocrine responsiveness should be the first consideration in tailoring adjuvant therapies for patients with breast cancer, regardless of age (52). Adjuvant chemotherapy has historically been used extensively in premenopausal patients because of its overwhelming beneficial effects on outcome (53). The incremental benefits of newer cytotoxic drugs and regimens, including the addition of the taxanes, dose density, and trastuzumab, appear to be present across age groups, although data for very young women are limited (54, 55, 56, 57 and 58).

Adjuvant Systemic Therapy in Patients with Hormone Receptor-Negative Disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree