Breast Cancer in Minority Women

Katherine E. Reeder-Hayes,

Stephanie B. Wheeler,

Lisa A. Carey

INTRODUCTION: A FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING BREAST CANCER DISPARITIES

The study of breast cancer in minority women is inevitably linked to the study of healthcare disparities. The Institute of Medicine has defined healthcare disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention” (1). In the context of breast cancer, disparities occur when a group within the breast cancer population experiences unequal access to cancer screening and diagnostic care, inferior cancer treatment, lower rates of response to anti-cancer therapies, poorer short term outcomes such as treatment toxicities or complications, or poorer long-term outcomes including breast cancer recurrence and death. The determinants of breast cancer disparities are complex and include biologic, behavioral, socioeconomic, provider, and structural factors. Breast cancer disparities are seen in a number of vulnerable populations including elderly and poor women, but have been best documented among racial and ethnic minorities and particularly among black women. In this chapter, we will summarize the existing literature regarding racial disparities in breast cancer, explore the most pronounced disparities among other vulnerable groups, and discuss potential areas for intervention and future research.

African American women with breast cancer die at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts, and this racial gap in survival persists despite overall improvements in breast cancer mortality over time (2). This core fact has motivated much of the breast cancer disparities research in the United States over the past three decades. From this core finding, a number of questions immediately arise. These questions and their answers can be imagined as layers to be unearthed in the search for the roots of breast cancer outcome disparities. Are racial differences in breast cancer mortality best explained by differences in cancer stage at diagnosis, tumor biology, treatments received, response to treatment, subsequent experiences during survivorship, or a combination of these factors? These questions are the starting point for the study of breast cancer disparities.

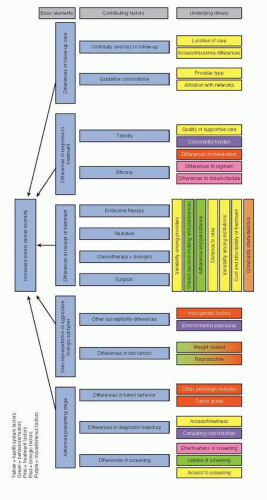

Known differences in stage at presentation, tumor biology, receipt of treatment, response to therapy, and survivorship care are the basic elements contributing to breast cancer outcome disparities. Once these basic elements are established, we turn to understanding the factors underlying each element. For instance, do black women present at a later stage due to inherently more aggressive disease, less effective screening, or delays in diagnosis? Do black women receive different breast cancer treatments for equivalent disease across the spectrum of care, including diagnostic and staging evaluation, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy? And do they respond to such treatments differently, in terms of both efficacy and toxicity?

Once the key drivers of breast cancer outcome disparities are defined, we can examine which factors may be amenable to change. As one example, a woman who presents with advanced breast cancer due to lack of screening may not have undergone breast cancer screening because she believes herself to be at low risk (behavioral factor),

because she cannot afford the cost of screening (socioeconomic factor), because her provider has not recommended screening (provider factor), or because there is no screening facility within a reasonable distance of her home (structural factor). This woman’s story is an example of a basic element of breast cancer outcome disparity (advanced stage at presentation) potentially explained by a particular factor (lack of screening) which in turn may have a number of drivers at the patient, provider, or health system level. To the extent that these drivers vary by race, ethnicity, age or other patient characteristics, they contribute to health disparities. Complex interactions between factors are also to be expected in the study of health disparities. A conceptual model of the multilayered factors contributing to breast cancer disparities is presented in Figure 86-1.

because she cannot afford the cost of screening (socioeconomic factor), because her provider has not recommended screening (provider factor), or because there is no screening facility within a reasonable distance of her home (structural factor). This woman’s story is an example of a basic element of breast cancer outcome disparity (advanced stage at presentation) potentially explained by a particular factor (lack of screening) which in turn may have a number of drivers at the patient, provider, or health system level. To the extent that these drivers vary by race, ethnicity, age or other patient characteristics, they contribute to health disparities. Complex interactions between factors are also to be expected in the study of health disparities. A conceptual model of the multilayered factors contributing to breast cancer disparities is presented in Figure 86-1.

OVERVIEW OF DISPARITIES IN BREAST CANCER

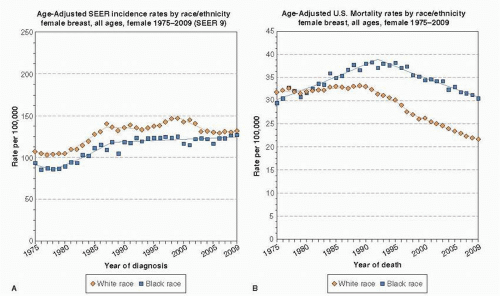

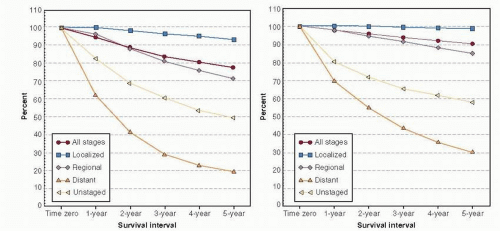

In the United States, new diagnoses of breast cancer are slightly more common in white women, but breast cancer mortality is higher among black women (2). In 2005-2009, the age-adjusted incidence rate of breast cancer was 127.3 per 100,000 women among whites and 121.2 per 100,000 among blacks, while age-adjusted death rates were 22.4 and 31.6 per 100,000 women among whites and blacks respectively (3). Although breast cancer incidence and mortality rates have declined for all racial groups over time, the gap between black and white patients has not closed and in fact appears to be widening (4). Figure 86-2 demonstrates the trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality among black and white women. Racial and ethnic trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality vary depending on age. Specifically, younger black women (those <50 years old) have a higher incidence of breast cancer compared to younger white women, but beginning around the time of menopause, incidence rates among white women surpass rates of black women, and remain higher throughout the older years (5, 6). Although advanced stage at presentation will be discussed in this chapter and clearly contributes to poor breast cancer outcomes, a marked stage-specific survival gap remains after controlling for basic stage and hormonal status differences among newly diagnosed patients, as depicted in Figure 86-3. Race remains an independent predictor of poor survival after controlling for tumor size, grade, and year of diagnosis (7). In this chapter, we will examine in detail the major factors underlying disparities in breast cancer mortality—differences in stage at presentation, biology, receipt of treatment, treatment response, and survivorship care—and their drivers.

DISPARITIES IN PRESENTING STAGE

One well-documented contributor to higher breast cancer mortality among black women is advanced stage at presentation. Table 86-1 shows the percentage of women in the national Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database presenting with various stages of breast cancer between 2000 and 2009. Black women present more often than their white counterparts with regional or distant breast cancer, and less often with localized or early stage breast cancer (3). Given that cancer stage at diagnosis is a strong predictor of breast cancer survival (7), it is straightforward to understand why advanced presenting stage is associated with poor outcomes among black women. Less clear are the reasons why black women present at a later disease stage. Differences in screening patterns, diagnostic trajectory after a cancer is suspected, and risk of aggressive cancers that may arise in the interval between regular screenings may all contribute to late-stage diagnoses.

Screening Disparities

Modern mammography screening clearly reduces the risk of late-stage breast cancer diagnosis (8). Late-stage diagnosis of breast cancer in black women has historically been attributed to screening behaviors, specifically underuse of screening mammography or lack of diagnostic follow-up after an abnormal mammogram result (9). Overall use of screening mammography has risen over the past two decades, but the equivalence of mammography use among racial/ethnic groups is a subject of ongoing debate, with some studies showing equivalence and others suggesting that black women remain less likely to get mammograms at the recommended 1- to 2-year interval (9, 10, 11). Although screening is associated with early diagnosis among all racial groups, this association appears weaker in black women (12) and differential performance of mammography does not appear related to higher mammographic breast density among black women (13). This finding may instead be explained in part by the quality of mammography services received; one recent study found that black and Hispanic women were less likely than white women to have their mammograms at academic centers, facilities that used breast imaging specialists to interpret mammograms, and facilities with digital mammography (14). Provider factors also may contribute to disparities in receipt of mammography. Black women more often than white women cite lack of physician referral or recommendation for mammography as the reason they failed to receive the test (15).

Disparities in Diagnostic Workup

Completion of a diagnostic workup is an important step intervening between a screening or physical exam abnormality and initiation of treatment. Evidence suggests that racial disparities exist in the timeliness of diagnostic workup for breast cancer. Two studies in vulnerable populations have suggested that even among uniformly low income women, and after controlling for the effect of insurance status and income, black women experience longer delays between initial abnormal mammogram or exam findings and the final determination of a pathologic diagnosis (16, 17). Large population-based studies confirm race as an independent predictor of diagnostic delays, with a greater disparity among women who present with physical symptoms compared to screening abnormalities (18, 19). Cultural beliefs and attitudes, for example, the fear that cancer can be spread through the air during a diagnostic procedure, have been found to partially explain racial disparities in timeliness of diagnostic workup (20). Longer times between symptom onset and definitive pathologic diagnosis are associated with higher mortality (21).

RACIAL DIFFERENCES IN BREAST CANCER BIOLOGY

Persistent survival gaps between blacks and whites diagnosed at similar stages of illness (22) and with similar access to healthcare (23) have led researchers to suggest that breast cancer in black women may be fundamentally biologically different from that in white women. Early observations supporting this hypothesis include findings that, within a given stage, black women are more likely to have larger tumors and positive lymph nodes. However, McBride

and colleagues found that controlling for such within-stage differences did not attenuate differences in mortality (24). Thus, racial differences in outcome among similar-stage women do not appear to be due primarily to more advanced disease among black women within each stage grouping.

and colleagues found that controlling for such within-stage differences did not attenuate differences in mortality (24). Thus, racial differences in outcome among similar-stage women do not appear to be due primarily to more advanced disease among black women within each stage grouping.

TABLE 86-1 Percentages of Women in SEER 18 Registry Regions Presenting with Localized, Regional, and Distant Disease 2000-2009 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

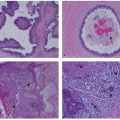

Histologic features of breast cancers also vary by race and ethnicity. While differences in presenting stage largely disappear when mammography is received equally, black women still have significantly more high-grade breast cancers (10). Chen and colleagues found that after adjusting for age, stage, socioeconomic status, body mass index, reproductive history, insurance status, and location, black women with invasive breast cancer were more likely to have high grade nuclear atypia, high grade tumors, and more necrosis compared to white women (25). Black women are also more likely to have overexpression of cell-cycle regulators, such as Cyclin E, p16, and p53, and polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes (26). All of these results provide a strong argument for biological differences between black and white women in breast cancer.

Perhaps the most striking example of biological differences between breast cancers in black and white women occurs in biologic “subtype,” which refers to the profile of cell surface receptors expressed by the cancer, including estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and human epidermal receptor type 2 (HER2). Immunohistochemical analyses of tumors from women in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study (CBCS) and other population-based studies have found that a significantly lower proportion of black women have favorable prognosis ER or PR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer compared to whites, and a correspondingly higher proportion of black women, particularly younger black women, have poor prognosis triple negative (ER-, PR-, and HER2-negative) breast cancer (27, 28 and 29). Similar analyses of a West African cohort of breast cancer patients also found a high incidence of triple negative breast cancer (30). As molecular subtyping of breast cancers becomes more widespread, we expect that previously unappreciated biologic differences by race may also be found.

Recent studies have shed light on potential epidemiologic differences underlying racial differences in distribution of breast cancer subtypes. Reanalysis of the CBCS and other epidemiologic studies have suggested that the effect of traditional breast cancer risk factors, including reproductive history and weight-related factors, vary by biologic subtype (31, 32). Some risk factors, including early age of menarche, centripetal obesity, or the protective effect of breast-feeding, are far stronger for basal-like breast cancer (the molecular correlate of triple negative breast cancer) than for hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Other factors actually appear to have opposite effects in different subtypes. For example, multiparity and young age at first full-term pregnancy, which have historically been identified as protective factors in breast cancer epidemiology, appeared protective only for luminal breast cancer (the molecular correlate of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer), while both appeared to be risk factors for basal-like breast cancer (31). These studies suggest that race-associated differences in lifestyle or hormonal exposures may partially explain variations by race in breast cancer subtype. Recent genome-wide association studies implicate novel risk variants for breast cancer in women of African ancestry as another contributor (33). It is clear, however, that biological factors cannot explain all of the racial disparity in morbidity and mortality because black women experience worse long term outcomes even when compared to white women with biologically similar disease (9, 22, 27).

DIFFERENCES IN RECEIPT OF TREATMENT

Background on Cancer Treatment Quality

Although presenting stage and biologic factors are important determinants of breast cancer prognosis and treatment, these factors do not fully explain racial disparities in outcomes. If minority women receive less-than-standard treatment, we might expect to see continuing differences in outcomes, even after controlling for stage at presentation and biologic differences. Differences in treatment are now the focus of many studies examining breast cancer disparities. A large body of research shows that racial disparities exist in overall receipt and timeliness of treatment as well as monitoring of treatment-related toxicities (34, 35, 36 and 37). Failure to receive appropriate treatment is an important cause of racial disparities in breast cancer mortality (38).

Evidence of Racial Variation in Quality of Breast Cancer Treatment

Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of breast cancer (39) and metrics to evaluate breast cancer care quality (40) are widely available in the United States. Despite the existence and widespread dissemination of these guidelines and quality metrics, many patients—in particular, black women—do not receive high quality, guideline-concordant care. Studies of treatment disparities have focused on the receipt of mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy (BCT, defined as breast conserving surgery [BCS] followed by radiation therapy), receipt of radiation when breast conserving surgery is chosen, receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, and receipt of endocrine therapy when appropriate. Some studies have also attempted to use aggregate measures of high quality breast cancer care. The ability to accurately measure these treatments and to adequately control for confounders of the race-treatment relationship, such as socioeconomic status and comorbidity, varies from study to study depending on the data source. We describe some of the most significant studies documenting treatment disparities, their findings, and limitations.

Using inpatient and outpatient medical records from six New York City hospitals, Bickell and colleagues found that 34% of black women and 23% of Hispanic women, compared to 16% of white women, failed to receive appropriate adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer. Appropriate treatment included radiation therapy after BCS, adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery among patients with hormone receptor-negative tumors at least 1 cm in size, and

endocrine therapy among patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors at least 1 cm in size (34). In multivariate models, poor quality care was significantly associated with black or Hispanic racial/ethnic status, lack of medical oncologic referral, having more comorbid conditions, and lack of insurance. Black and Hispanic women were more than twice as likely to receive poorer quality care, after controlling for all other factors. Consulting with a medical oncologist attenuated but did not entirely eliminate the racial disparity (34).

endocrine therapy among patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors at least 1 cm in size (34). In multivariate models, poor quality care was significantly associated with black or Hispanic racial/ethnic status, lack of medical oncologic referral, having more comorbid conditions, and lack of insurance. Black and Hispanic women were more than twice as likely to receive poorer quality care, after controlling for all other factors. Consulting with a medical oncologist attenuated but did not entirely eliminate the racial disparity (34).

Lund and colleagues examined first course of treatment among women diagnosed in 2000-2001 with invasive breast cancer in five Atlanta SEER counties (2008). In this analysis, black women were four to five times more likely to experience significant treatment delays. Black women also were less likely to receive cancer-directed surgery, radiation therapy after BCS, and endocrine therapy for hormone receptor positive tumors, after controlling for age, tumor size, stage, lymph node involvement, and ER/PR status (36). As with many observational studies, this analysis was limited by lack of information about treatments beyond the 4-month time window after diagnosis, inability to capture HER2 status, lack of information about comorbidities, and lack of information about provider and system-level characteristics.

In a study of newly diagnosed stage I and II breast cancer patients 65 and older using Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data, investigators evaluated disparities in receipt of BCT, documentation of hormone receptor status, surveillance mammography during remission, and a combined measure of adequate care (41). In adjusted comparisons, Hispanic women were 33% less likely to receive adequate care, and black women were 23% less likely to receive adequate care, compared to white women. Black/white disparities actually worsened over time. Older women and those from rural areas were also significantly less likely to receive standard quality care, controlling for other factors. Banerjee and colleagues assessed receipt of BCT, endocrine therapy, and chemotherapy by conducting comprehensive medical record reviews of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Detroit at the Karmanos Cancer Institute and found that for local disease, white and black women received equivalent care, but for regional disease, black women were less likely to receive guideline-recommended endocrine therapy and chemotherapy. The authors did not find a racial disparity in receipt of BCT versus mastectomy, but they did note that women with Medicare or Medicaid insurance were more likely to receive mastectomy than those with private insurance. They also found that black women had far more comorbid conditions than white women, highlighting the need to control for comorbid illnesses in future analyses to avoid potential confounding (42). Because this study was limited to one institution in an area with many older, insured, black women of low socioeconomic status, the effect of variations in rural/urban residence, income and education, neighborhood racial composition, insurance status, and ethnic identity could not be easily assessed.

In a study by Freedman and colleagues (2009), SEER data from 1988 to 2004 were used to assess definitive local treatment (i.e., mastectomy or BCT) for early stage cancers. Over time, rates of mastectomy decreased as BCT diffused into practice; however, in adjusted models, rates of any definitive treatment remained lower for black and Hispanic women compared to white women, and no reduction of this disparity was observed over time (35). This analysis controlled for biologic tumor features, year of diagnosis, and region, but lacked information about employment, insurance status, and comorbidities, and did not control for possible organizational confounders.

Several studies have also found that black women more often experience delays in adjuvant therapy, which may affect longer-term health outcomes (18, 37, 43, 44). One study using SEER-Medicare data explored variation in timing of receipt of radiation therapy after BCS and found that a substantial minority of breast cancer patients 65 years and older never received guideline-recommended radiation therapy after BCS. Further, among those women who did receive radiation therapy, black women more often experienced delays in initiation of therapy (37). After controlling for region-level resources, hospital facility-level factors, and patient-level factors, delayed initiation of radiation after BCS remained more common among black women compared to white women, although the Hispanic disparity resolved (37). Other studies have documented delays in time to first treatment among black women. Among young women with incident breast cancer (ages 20-54) in Atlanta, 22% of black women compared to 14% of white women experienced delays of greater than 3 months from diagnosis to first treatment. Access to care and poverty partially accounted for these delays, but significant racial differences in delays remained even after adjustment for all other factors (45).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree