20722

Bladder and Renal Cancer

Ravindran Kanesvaran

BLADDER CANCER IN THE ELDERLY

Cancer is a disease of aging, and bladder cancer (BC) is a classic example of the interaction between cancer and aging. The median age of diagnosis of BC in the United States from the period 2008 to 2012 was 73 years (1). It is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States, with a predominant majority of patients being elderly (1). The management of BC in the elderly is complicated by their functional status and the numerous other comorbidities that afflict them. Hence, it is important for these patients to get a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in order to better stratify them into the appropriate treatment group. Numerous CGA-based studies have found it to be an important tool that can not only prognosticate but also predict treatment toxicity and treatment selection (2–4). In general, these patients can then be classified into three categories—the fit patients, the vulnerable patients, or the frail elderly patients (5). In this chapter we review the data pertaining to the numerous treatment modalities that are used for the treatment of BC and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in the elderly, taking into account their general state of health and their CGA results.

Superficial BC

The recommendation for the fit elderly BC patient will be to undergo a complete transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) and intravesical therapy. There are limited data describing the benefit of intravesical therapy in elderly BC patients with nonmuscle invasive disease. A single-institution study that stratified patients into those aged above and below 70 years with superficial BC found that older patients had a higher risk of cancer recurrence in spite of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) intravesical therapy (6). In another Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database study, overall survival (OS) for this group of patients appears to be longer when treated with adjuvant BCG therapy compared to those without it (7). Based on the CGA, frail patients may be limited in terms of the treatment options available for them. Treatment of patients with low-risk disease with TURBT may be appropriate and can be done under regional anesthesia if they are unfit for general anesthesia. Even intermediate and high-risk frail patients can receive intravesical BCG, as it is a low-risk local procedure. However, those patients with a short predicted life expectancy should just be treated expectantly for any symptoms that may arise from the disease.

208Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer

Muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is defined as cancer that has invaded the muscularis propria of the bladder wall (T2 disease and beyond). Treatment for localized MIBC involves multimodality therapy. Hence, apart from a CGA to assess the fitness of the patient to receive these various treatment modalities, it is also important for these cases to be discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board setting.

RADICAL CYSTECTOMY

Fit elderly MIBC patients should receive radical cystectomy as part of their treatment if the intent is curative. However, patient selection is important in order to reduce the risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality associated with the surgery. In age-unselected populations, the morbidity and mortality from radical cystectomy from a large number of studies range from 30% to 70% and 0.3% to 7.9% respectively (8). The development of nomograms has helped with predicting 90-day survival and complication rates from this procedure with reasonable accuracy (8,9). Nonetheless, apart from the risk stratification based on nomograms, increasing age by itself seems to predict poorer outcomes and is associated with worse cancer-specific outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy (10). The urinary diversion tends to contribute to the postsurgical complications experienced by elderly patients. Still, older patients who tend to receive ileal conduits seem to report no difference in terms of diversion-related complications, operative mortality, and quality of life (QOL) compared to those who had orthotopic bladder surgery (11). There are a number of surgical techniques that can be used to perform the radical cystectomy, though there is limited data regarding the use of these modalities specific to elderly MIBC patients (1). One meta-analysis looking at laparoscopic versus open radical cystectomy reported lower intraoperative blood loss but longer operative time with laparoscopic surgery (12). In a randomized study in older MIBC patients, robot-assisted radical cystectomy, which is gaining popularity of late, has shown findings of lower blood loss and longer preoperative time, but was found to have similar lengths of stay when compared to the open surgery group (13). In summary, elderly MIBC patients who are fit should receive radical cystectomy as the standard of care after a careful assessment using some of the validated nomograms for postoperative mortality and morbidity. The choice of urinary diversion and surgical method can be made after a discussion with the patient based on the evidence described earlier and the level of expertise available in the particular center.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy plays an integral role in the treatment of MIBC patients. It can be used in the neoadjuvant setting, adjuvant setting, or together with radiotherapy as concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in MIBC treatment. Cisplatin is a key component of two of the proven chemotherapy combinations used in the treatment of MIBC; together with gemcitabine (GC) or together with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin (MVAC). However, due to its significant toxicities, it can only be used for a select group of patients known as cisplatin-eligible MIBC or metastatic BC patients as defined by a consensus group statement published in 2011 (14). The inclusion criteria for cisplatin-eligible patients are based on their performance status, creatinine clearance, degree 209of hearing loss, degree of peripheral neuropathy and New York Heart Association classification (15). For cisplatin-eligible patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with MVAC for treatment of MIBC would be the treatment of choice prior to radical cystectomy based on improvement of OS as reported in a large meta-analysis (16). Unfortunately, trials on adjuvant therapy for MIBC have failed to show a statistically significant OS benefit due to poor accruals (17). Thus, the preferred treatment approach should be with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. As all these data were drawn from all persons enrolled into the studies and were not specific to elderly MIBC patients, these patients should be assessed for their risk of getting grade 3 to 5 chemo-related toxicities based on available chemo-toxicity prediction tools that have been developed (3). A review of how to treat BC in the elderly nicely summarizes the lack of data for elderly patients and how best to extrapolate from available data to treat this group of patients (18).

CHEMORADIOTHERAPY

For select elderly MIBC patients who are unfit for surgery or are keen for a bladder-sparing approach, concurrent CRT may be a suitable option. These patients should have no invasion of adjacent viscera, no nodal involvement, no carcinoma in situ, and no disease near the bladder trigone with hydronephrosis. They should have had maximal TURBT and most importantly be found to be fit enough to tolerate concurrent CRT. Thereafter, these patients should comply with surveillance cystoscopy and, should any recurrence be detected, be prepared for a radical cystectomy. A number of elderly-specific studies have shown promising data, with complete response and disease-free survival rates comparable to patients who had undergone radical cystectomy (19). In a pooled analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) studies, though older patients were less likely to complete CRT compared with younger patients, they reported similar complete response rates, bladder preservation rates, and disease-specific survival rates as their younger counterparts (20). In summary, CRT is a reasonable curative option to consider in elderly cancer patients who desire bladder preservation. Frail MIBC patients are unlikely to be candidates for radical cystectomy or CRT, but they can be offered palliative care for symptom control. RT alone can be considered a reasonable palliative option for these patients, as it may help control symptoms like pain and hematuria and also slow down the growth of the tumor (21).

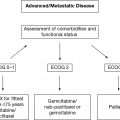

Metastatic Bladder Cancer

The OS from metastatic bladder cancer (MBC), even with combination chemotherapy, is relatively poor at about 1 year on average (22). The current standard of care for fit MBC patients in the first line would be to use either MVAC or GC chemotherapy. A phase 3 study comparing both these regimens reported comparable survival outcomes with increased toxicities from the use of MVAC (22). Hence, GC has become the treatment of choice in fit cisplatin-eligible elderly MBC patients. For those who are cisplatin-ineligible, carboplatin may be substituted with similar outcomes and lower toxicity when compared to MCV (methotrexate, carboplatin, and vinblastine) chemotherapy (23). In the very near future, immune checkpoint inhibitors may be an important therapeutic option with a tolerable side effect profile that elderly MBC patients can avail themselves of (24). 210Frail elderly MBC patients can either be given single-agent GC chemotherapy (25) or offered best supportive care with palliative treatment for symptom relief.

RCC IN THE ELDERLY

RCC is predominantly a disease afflicting the elderly, with a median age of diagnosis of 64 years. It is a heterogenous group of histopathologic subtypes, with clear cell carcinoma being the dominant subtype accounting for more than 75% of all RCCs. About 30% of RCC patients are metastatic at diagnosis, and recurrence rates of those treated for localized disease are as high as 50%. All elderly RCC patients should get a CGA done as well. Currently, the only available treatment guideline specific to the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in elderly patients is the one developed in 2009 by a SIOG task force (26).

Localized RCC

FIT ELDERLY PATIENT WITH LOCALIZED RCC

In a fit elderly patient, there are a number of options to treat a localized RCC. These options vary depending on the size and site of the tumor. For solitary RCC that is 4 cm or larger, the treatment of choice would be a radical nephrectomy (RN). This can be done safely laparoscopically, with one study showing reduced morbidity in terms of genitourinary complication rate and blood loss in elderly RCC patients compared to laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (PN) or open PN (27). With the rampant use of imaging in the investigation of symptoms in elderly patients, there has been an increase in the detection of small renal masses (<4 cm), of which a substantial number are RCC (28). In fit elderly patients, nephron-sparing surgeries are the treatment of choice for localized small RCCs based on their location. In certain locations, PN may not be possible, necessitating use of RN in those circumstances. There are currently no data to support any form of adjuvant therapy following surgical resection of the RCC (29). Therefore, these patients should be on an active surveillance protocol, although there is currently no consensus on the exact frequency of imaging in the various guidelines (30).

FRAIL ELDERLY PATIENT WITH LOCALIZED RCC

Frail elderly patients with a solitary renal mass may not have many treatment options available to them. For large tumors (≥4 cm), these patients may not be fit for any form of surgery and will be treated expectantly for symptom control with palliative care. However, they may have more options with local ablative therapy if they have small RCCs (<4 cm). The common methods of ablative therapy are radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or cryoablation. A systematic review comparing cryoablation versus PN reported higher rates of tumor progression with cryoablation, but both had similar low rates of distant metastases of less than 2% (31), hence making it a suitable option for the frail elderly patient. Another feasible option for the frail elderly RCC patient would be active surveillance of a small RCC (32).

Metastatic RCC

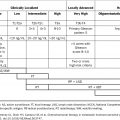

Since 2005, a number of targeted therapies have been developed that have revolutionized the way we treat elderly mRCC patients. Apart from high-dose interleukin-2, 211which has shown efficacy in a small group of younger patients, there are no data to support cytokine use in the elderly (33). These mRCC patients should first be stratified into the appropriate prognostic risk group as defined by either the MSKCC or IMDC criteria (34). Table 22.1 shows the various phase 3 clinical trials that have led to the approval of the targeted therapies for use in the different settings in the treatment of mRCC. Data for the elderly can be extrapolated from these phase 3 studies, as about one-third of the patients enrolled in them were over 65 years of age (26). A study comparing patient preference between sunitinib and pazopanib reported that a majority of patients prefer pazopanib due to its better toxicity profile and QOL (44). Although this was not an elderly-specific study, the lower toxicities and better QOL assessment make it a suitable choice for the elderly.

For MSKCC poor risk (PR) patients, temsirolimus—though the drug of choice—has not been shown to increase survival in patients over 65 years of age compared to interferon (IFN) (38). In the second-line setting, there are a number of drugs approved for use (Table 22.1). Recently reported studies indicate that treatment with nivolumab (PD1 inhibitor) or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib may be suitable options for elderly mRCC patients after they were found to have superior efficacy and better tolerability when compared with everolimus (39,40). Although these drugs have shown that they are reasonably well tolerated in the younger population in which they were tested, it is important to note that elderly patients have a multitude of other issues (such as comorbidity, decreased physiological reserve, and polypharmacy) that must be taken into account before they are treated with these drugs.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree