314

Biologic Markers of Frailty

Kah Poh Loh, Nikesha Haynes-Gilmore, Allison Magnuson, and Supriya G. Mohile

BIOLOGIC MARKERS OF FRAILTY

Older adults with cancer are a heterogeneous population, and their chronologic ages may not be reflective of their physiologic ages. Geriatric assessment (GA) to evaluate the overall health status of an older adult with cancer influences treatment decision making by providing a more accurate assessment of physiologic age (1,2). Several biologic markers correlate with aging and frailty and may offer a better assessment of physiologic age. In combination with GA, the use of biologic markers may better be able to personalize oncologic treatments in older adults in the future (Table 4.1).

Inflammation plays a vital role in the process of aging. Older adults often have low-grade, chronic systemic inflammation characterized by elevated circulating serum levels of white blood cells (WBCs), C-reactive protein (CRP), CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) along with their cognate receptors (3). This heightened inflammatory state with aging is associated with an increased risk of morbidity and frailty. In a cross-sectional study of 558 women (aged 65–101), odds of frailty were four times higher in patients in the top tertile of WBC count and IL-6 than those with levels in the bottom tertile (4). Elevated circulating serum levels of IL-6 have also been shown to cause atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, functional decline, and disability which ultimately may lead to mortality in this population (5). Additionally, patients with a cancer diagnosis and higher levels of IL-6 and CRP had higher odds of death compared to those without elevation of the markers, with hazard ratios of 1.64 and 1.63, respectively (5). Similarly, a high WBC count was also associated with frailty and mortality from cancer. The individual immune cell components may contribute differently to the frailty phenotype. In one study, increased levels of neutrophils and monocytes, but not lymphocytes, were positively associated with frailty, disability, and mortality (6). The direct correlation between WBC count and its subpopulations and frailty remains to be further elucidated.

Prothrombotic factors (fibrinogen, factor VIII, and d-dimers) and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule (s-VCAM) are noted to be increased in parallel with chronic inflammatory markers due to the costimulatory and downstream effects between these pathways. In a large population cohort study involving 4,735 community-dwelling 32adults 65 years and older (15% had cancer), those who were frail had higher levels of fibrinogen and factor VIII, independent of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (7). High d-dimers, s-VCAM, and IL-6 levels were also independently associated with 4-year mortality (3).

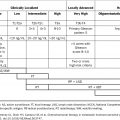

TABLE 4.1 A Summary of Biomarkers of Frailty

Markers | Examples |

Inflammation (including acute phase reactants) and coagulation system | High levels of CRP, IL-6, WBC, CXCL10, TNF-α, fibrinogen, factor VIII, d-dimers, s-VCAM |

Endocrine markers | Impaired glucose tolerance, high cortisol level, and low levels of IGF-1 and DHEA-S |

Cellular senescence | Telomere shortening, high levels of P16ink4a |

Imaging | Sarcopenia (measurement of skeletal mass using whole-body DEXA or CT scan cross-sectional imaging) |

CRP, C-reactive protein; CXCL10, CXC chemokine ligand 10; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IL-6, interleukin-6; P16ink4a, cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/CDK6) inhibitor p16; s-VCAM, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; WBC, white blood cell.

Endocrine biomarkers also correlate with aging and frailty. In a group of 102 women, older age was inversely associated with the levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and DHEA-S deficiency was also a predictor of bone loss (8). When compared to nonfrail community-dwelling older adults, serum levels of IGF-1 and DHEA-S in the frail population were significantly lower (9). The association was supported by a 10-year longitudinal study in which lower levels of DHEA-S (odds ratio [OR], 0.50) and higher cortisol-to-DHEA-S ratio (OR, 1.79) were predictive of frailty (10).

Telomeres are structures that cap the ends of DNA to avoid chromosomal damage. Telomere length shortens with aging, and correlates with senescence, apoptosis, and oncogenic transformation of somatic cells (11). Multiple studies have demonstrated that telomere length correlates with disability as well as with cancer and all-cause mortality (11). Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/CDK6) inhibitor pI6 (P16ink4a) is a tumor-suppressor protein which inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity in the cell cycle (12). Prolonged expression of p16INK4a can induce irreversible cell cycle arrest and promote senescence (12). In animal and human models, this expression was found to be elevated with aging. Although in theory telomere length and P16ink4a could serve as biomarkers of aging, associations between frailty and mortality must be investigated further.

Sarcopenia is the loss of muscle mass associated with aging, and is defined as muscle mass that is two standard deviations below that of a healthy adult. Methods to assess muscle mass include whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (four limbs) and CT cross-sectional imaging (lumbar muscles). Sarcopenia may contribute to frailty and thus these entities can be difficult to separate from one another (13). A meta-analysis demonstrated that low muscle mass was associated 33with decreased survival in patients with nonhematological cancers (14). Sarcopenia was also found to be predictive of postoperative complications in patients undergoing oncologic surgeries (15,16).

In conclusion, the interplay between frailty and biomarkers is complex, and is often affected by comorbidities and underlying diseases. Further studies are needed to validate the feasibility and utility of biomarkers in the geriatric oncology setting to help predict frailty, disability, treatment toxicities, and prognosis. More studies are needed to evaluate if biomarkers of aging can be modified by interventions and if these changes are correlated with outcomes. Of the various biologic markers, serum IL-6 has been studied most extensively. However, the exact mechanism by which IL-6 influences the pathophysiology of frailty, including how it interacts with other up- and downstream molecular and cellular immune factors, has yet to be elucidated.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree