Abstract

This chapter presents a histopathologic classification of the wide variety of noncancerous lesions identified in the human female breast, stratified into categories that predict breast cancer risk in broad terms. The magnitude of risk in these various groups is based on the following assumption: any change that does not indicate an increased risk of subsequent breast cancer greater than 50% above that for women controlled for similar age and length of time at follow-up is assigned no elevation of risk. Many of these lesions are not associated with cellular proliferation and are designated as nonproliferative. Nonproliferative lesions may result in biopsy or present clinical symptoms without an association of increased risk. Other lesions that maintain an association with subsequent breast cancer risk are defined as proliferative lesions.

Keywords

benign breast disease, risk, pathology, atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia, flat epithelial atypia, columnar cell change, radial scar, fibroadenoma, papilloma

This chapter presents a histopathologic classification of the wide variety of noncancerous lesions identified in the human female breast, stratified into categories that predict breast cancer risk in broad terms. The magnitude of risk in these various groups is based on the following assumption: any change that does not indicate an increased risk of subsequent breast cancer greater than 50% above that for women controlled for similar age and length of time at follow-up is assigned no elevation of risk. Many of these lesions are not associated with cellular proliferation and are designated as nonproliferative. Nonproliferative lesions may result in biopsy or present clinical symptoms without an association of increased risk. Other lesions that maintain an association with subsequent breast cancer risk are defined as proliferative lesions.

Benign Lesions Without Cancer Risk Implications

Benign breast conditions have a diverse array of clinical presentations. The subjective discomfort of mammary pain and clinical signs of lumpiness have little correlation with histologic alterations. Lumpiness on physical examination is common to many benign and malignant situations. The continued use of such broad terms of convenience as fibrocystic disease or fibrocystic change and benign breast disease occurs because these terms are deeply embedded in clinical parlance. Despite their imprecision, these terms have utility precisely because of their imprecision, familiarity, and wide reference. The term benign breast disease is an intrinsically imprecise term that refers to all noncancerous lesions of the breast. The use of the term fibrocystic disease has been problematic despite its intent of providing a clinicopathologic correlation between lumpiness and histologic alterations. The difficulty probably arises from the use of the word disease, which has reinforced the widely held belief that cancer risk was elevated in this setting. With the introduction of fibrocystic disease in the 1940s, an association with cancer was implied by concurrent associations. Using the term fibrocystic change should remove the implication of cancer risk. In surgical pathology or histopathology, these terms had no precise reference and provide no clear understanding of pathogenesis. The following discussion highlights anatomic pathology while acknowledging that histopathology is an empty exercise without clinical correlates and predictability.

Although it may be difficult to draw sharp borders of definition for these changes, it is certain that they occur in more than 50% of the immediately premenopausal women in North America. The presence of cysts without hyperplasia and other epithelial proliferation does not identify a group of women who have an increased risk compared with others of the same ethnic or geographically defined group. Hyperplastic changes may be more common in breasts that are clinically lumpy, but no formal recent analysis of co-occurrence of these conditions is available. Similarly, reliable mammographic correlates of epithelial hyperplasia are not at hand. Mammograms with increased density have imperfect associations with histologic findings because fibrosis is as common as hyperplasia, although hyperplastic lesions are somewhat more common in dense breasts.

Histopathology of Benign Breast Disease

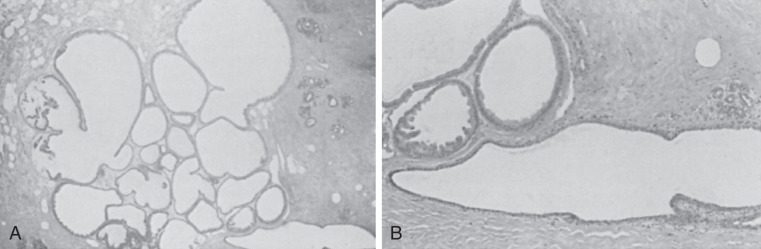

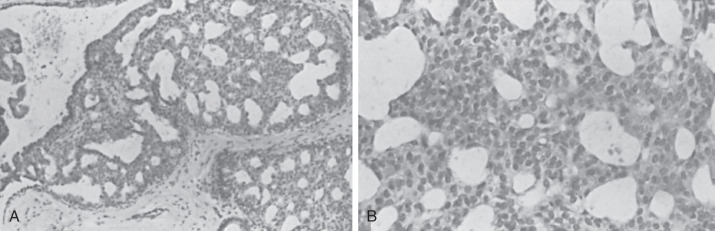

The most common benign histologic change in the breast is the presence of cysts often lined by pink apocrine cells. Cysts range from approximately 1 mm to many centimeters. Cysts are usually unilocular within the breast, resulting from dilatation, unfolding, and coalescence of individual terminal duct lobular units ( Fig. 8.1 ). Small cysts are often inapparent on gross tissue examination. Associated fibrosis may make smaller cysts palpable or more evident with imaging. These clinical correlates have become less important, particularly when most accept the fact that a biopsy may be appropriate based on clinical or imaging findings, even if histopathology demonstrates no specific abnormality. Understandably, fibrosis is often reported by pathologists in an attempt to explain clinical palpability or mammographic density. The gross appearance of large cysts is often blue, a reflection of the slightly cloudy, brown fluid usually found within.

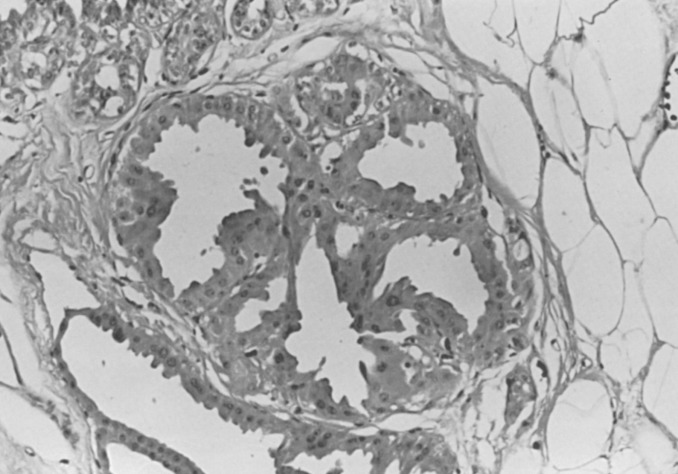

Many cysts are lined by cells that have characteristic cytologic features of apocrine glands. The cells have many mitochondrial-lysosomal and secretory granules that appear pink with eosin staining. The nuclei are round and often have a prominent round and eosinophilic nucleolus. This epithelium is often columnar, with a single protuberance of the apical aspect of the cytoplasm appearing as a bleb or snout. Such changes may be prominent in enlarged lobular units and may have minor associations with concurrent atypical lesions. The apocrine cells are often grouped in tufted or papillary clusters and sometimes produce prominent papillary prolongations from the basement membrane region, which may or may not contain fibrovascular stalks ( Figs. 8.2 and 8.3 ). This papillary apocrine change may demonstrate highly complex patterns but is not associated with a significant increased risk of later cancer development unless there is concurrent atypical hyperplasia (AH) (see later discussion). Breast cysts, particularly larger ones, may show no evidence of epithelial lining or may have a simple squamous lining with an extremely flattened and undifferentiated epithelialized surface. Several studies have differentiated these two types of cysts, apocrine and simple, indicating that apocrine cysts have a high potassium content and different steroid hormones. A suggestion of a difference in cancer risk between the two kinds of cysts is unproven. Apocrine cysts are probably more commonly associated with multiplicity and recurrence than are nonapocrine cysts. Whether this alteration of mammary epithelium to resemble that of apocrine sweat glands is a true metaplasia seems a point of practical irrelevance. However, many scholars believe that enzymatic profiles and ultrastructural evidence support a true metaplasia. Slight to marked protuberance of cell groups (papillary apocrine change) rather than a smooth, single cell layer is more frequent in the breast compared with the apocrine sweat glands.

Cysts alone are not associated with risk, even when larger ones are separately analyzed. Cysts are more common in high-risk geographic groups but are not determinants of cancer risk within geographic groups. Although epithelial hyperplasia is often associated with increased incidence of cysts and increased (albeit slight) cancer risk, either change may be present singly in an individual biopsy specimen or entire breast. The apocrine cytoplasmic alteration is also of no proven importance in breast cancer risk. Apocrine change was found by Wellings and Alpers to be more commonly present concurrently in breasts associated with cancer than those without. However, it is not an indicator of breast cancer risk in a predictive fashion. Moreover, papillary apocrine change without concurrent patterns of proliferative disease is not associated with an increased cancer risk. In summary, neither cysts nor apocrine change significantly elevate cancer risk in an individual woman in the absence of other considerations.

Chronic inflammation, edema, pigment-laden macrophages, and fibrosis are often found around cysts. Although duct ectasia and cysts have some histologic similarities, they are usually easily separable based on the general contour of the lesions and the greater degree of inflammation and/or scarring associated with duct ectasia ; furthermore, mammographic findings in duct ectasia are distinctive. Duct ectasia is usually present adjacent to the nipple, although it may extend a distance into the breast.

Epithelial Hyperplasia and Proliferative Breast Disease

The classification presented of epithelial hyperplasia in the breast is based on a large follow-up (cohort) epidemiologic study (and subsequently confirmed in other cohorts ) that sought to link epithelial histologic patterns to magnitudes of risk of breast cancer. The positive relationship of more extensive and complex examples of hyperplasia with carcinoma has been supported in many other prospective studies.

Definition and Background

Consistent with its definition elsewhere in the body, epithelial hyperplasia of the breast means an increased number of cells bounded by a basement membrane. Thus the increased number of glands without a concomitant increase relative to the basement membrane would not constitute hyperplasia but rather adenosis. Hyperplasia represents an increased number of cells above the basement membrane, and because this number is normally two, the presence of three or more cells above the basement membrane constitutes hyperplasia.

The intent of the term usual is to denote common patterns of cytology and cell relationships seen when cell numbers are increased within the basement membrane–bound spaces within the human breast. The usual type or common patterns of hyperplasia have also been termed ductal largely to contrast them with the lobular series. Because these lesions regularly occur within acini of lobular units, the designation of ductal is imprecise. Proliferative lesions in true ducts are unusual and are often truly papillary, that is, having branching, fibrous stalks (see later discussion).

The stratification of these hyperplastic lesions of usual type depends largely on quantitative changes. When the alterations begin to approximate patterns seen in carcinoma in situ, these lesions must be differentiated from those termed atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH). Note that the features on the lesser end of the spectrum, between mild and moderate hyperplasia of usual type, depend on quantity and that the differentiation of the larger lesions from ADH depends on qualitative features of intercellular patterns and cytology (see later discussion). Mild hyperplasia of usual type is characterized by the presence of three or more cells above the basement membrane in a lobular unit or duct and is not associated with any increased risk of cancer. Hyperplastic lesions that reach five or more cells above the basement membrane and tend to cross and distend the space in which they occur are called moderate . Florid is used for more pronounced changes, without any firm definition separating the moderate and the florid categories ( Fig. 8.4 ). The reason for this is not to deny that there are quantitatively lesser and greater phenomena but rather that their reliable separation is not accomplishable. Moderate and florid hyperplasia of the usual type is found in more than 20% of biopsies. In follow-up studies, the cancer risk between these two groups was found to be similar (see Chapter 20 ). The term papillomatosis, proposed by Foote and Stewart, may still be infrequently used in North America to indicate the common or usual hyperplasias of moderate and florid degree, and this practice is discouraged to prevent confusion with a diagnosis of a papillary lesion (see later).

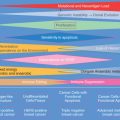

Risk categories may be stratified into slight, moderate, and marked, with slight indicating a risk of 1.5 to 2 times that of the general population and marked indicating about a 10-fold increased risk (see Chapter 20 ). The assignments of histologic parameters to risk groups is shown in Box 8.1 and has changed little from that presented by a consensus conference that was supported by the American Cancer Society and the College of American Pathologists. The clinical significance of usual hyperplasia of moderate and florid degree rests in the positive demonstration of a slightly increased risk (1.5–2 times) of subsequent invasive carcinoma.

a Women in each category are compared with women matched for age who have had no breast biopsy with regard to risk of invasive breast cancer in the ensuing 10 to 20 years. Note: These risks are not lifetime risks.

No Increased Risk (No Proliferative Disease)

Apocrine change

Duct ectasia

Mild epithelial hyperplasia of usual type

Slightly Increased Risk (1.5–2 Times)

Hyperplasia of usual type, moderate or florid

Sclerosing adenosis, b

b Jensen and colleagues have shown sclerosing adenosis to be an independent risk factor for subsequent development of invasive breast carcinoma.

papilloma

Moderately Increased Risk (4–5 Times) c

c Atypical hyperplasia or borderline lesions.

Atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia

High Risk (8–10 Times) d

d Carcinoma in situ.

Lobular carcinoma in situ and ductal carcinoma in situ (noncomedo)

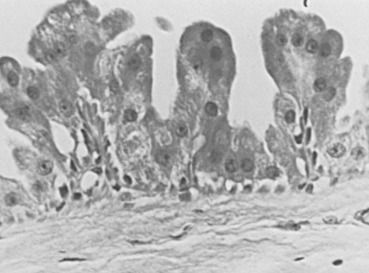

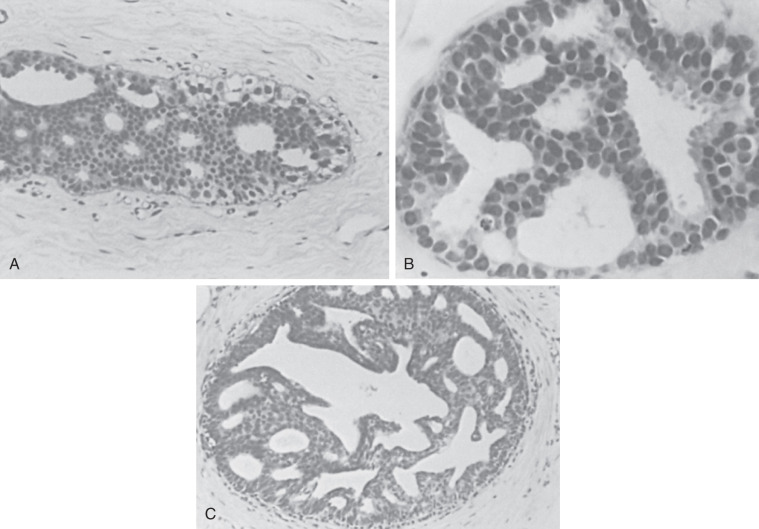

The positive histologic features of this group ( Figs. 8.5 to 8.7 ) are as follows:

- •

There is a mild variation in the size, placement, and shape of cells and, more specifically, nuclei. This feature is of great importance in differentiating these lesions from those of AH and noncomedo ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). They are most commonly present within lobular units and terminal ducts.

- •

The cells often exhibit patterns of swirling or streaming.

- •

As the epithelial cells proliferate, there is a varied shape of secondary lumens, which are often slitlike and are present between the cells within individual spaces.

- •

The secondary lumens, particularly in larger, more cellular lesions, may be present peripherally, immediately above the cells that surmount the basement membrane of the containing space.

- •

The cells appear to be varied, in cytologic appearance and in placement. Thus nuclei are not evenly separated one from the other, and cell membranes are not distinct. This is concomitant to the swirling or streaming change noted earlier.

Atypical Hyperplasia

The intent of the term atypical hyperplasia is to indicate a group of specific histologic patterns that are not generically “atypical” or “unusual” but for which the specific criteria have been shown to implicate an increased risk of later breast cancer development (see Box 8.1 ). The clinical significance of these specific histologic patterns is that women with AH have an approximately 1% per year risk of breast cancer, whereas women with benign or usual type hyperplasia have 0.5% risk per year. Of the tumors that developed after a biopsy diagnosis of AH in a large case-control study, 91% were estrogen receptor–positive, and 24% were lymph-node positive. The cumulative breast cancer risk over decades has clear implications for the consideration of preventive therapy (see Chapter 16 ).

The link of specific histologic patterns to a moderate magnitude of risk of breast cancer depends on the use of defined criteria. This link of AH lesions to risk is the result of a group of studies that sought to restrict the term atypical hyperplasia to a small number of histologic patterns that have some of the same features as the analogous carcinoma in situ lesions. Many prospective studies have supported the relationship of epithelial hyperplasia to premalignant states. There are conflicting data from large case-control studies on whether the extent of AH contributes to breast cancer risk.

Atypical hyperplastic lesions have some of the same features as those of carcinomas in situ but either lack a major defining feature of carcinoma in situ or have the features in less developed form. The three major defining criteria are cytology, histologic pattern, and lesion extent. Specific histologic features differentiate each of the AHs from lesser categories, as well as from the analogous carcinoma in situ lesions after which they are named: lobular and DCIS. Traditionally, the histologic definitions have not been viewed as resting within spectra of changes. On the contrary, these histologic categories represented an attempt to accept natural pattern groupings within the complex array of mammary alterations reflected in histologic preparations.

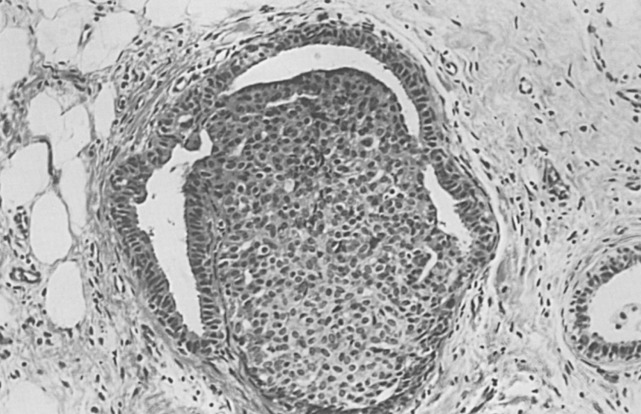

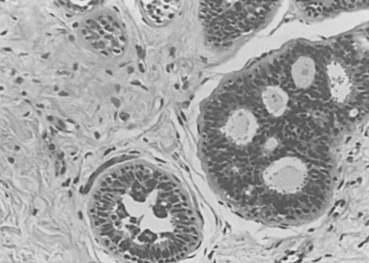

Lobular carcinoma in situ (see also Chapter 9 ) is recognized when there is a well-developed example of filling, distention, and distortion of over half the acini of a lobular unit by a uniform population of characteristic cells. This follows the intent of the original description. The analogous AH lesion, atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), is recognized when fewer than half of the acini in a lobular unit are completely involved, but the appearance is otherwise similar ( Fig. 8.8 ).

Histologically, ALH is characterized by a monomorphic epithelial cell proliferation that lacks cellular cohesion, often contains intracytoplasmic vacuoles, and expands less than 50% of a terminal ductal lobular unit. The separation of ALH and lobular carcinoma in situ imposes stratification on what is otherwise an undivided continuum. Many pathologists prefer to use one diagnostic term for this range of histologic appearances (e.g., lobular neoplasia). This term is valuable because it covers both ALH and lobular carcinoma in situ. However, in diagnostic practice, more clinical guidance is given by the use of the separate designations lobular carcinoma in situ and ALH.

A specific feature of lobular neoplasia is its tendency to undermine an otherwise normal luminal epithelial layer. Because this is the interposition of an abnormal epithelial cell population within another, it has been termed pagetoid spread (because of the obvious analogy to Paget disease of the nipple). Some have equated this pattern with lobular carcinoma in situ; however, pagetoid spread does occur when the degree of involvement within lobular units reaches only the diagnostic level of ALH. The histologic patterns produced are usually more subtle in ALH, without the solid pattern of ductal involvement seen in lobular carcinoma in situ. This pattern of involvement of ductal spaces outside of lobular units by the cells of lobular neoplasia in the presence of ALH has been termed ductal involvement in atypical lobular hyperplasia . In the past, the cancer risk associated with ALH was thought to be equal for both breasts. However, long-term follow-up from the Nashville cohort and the Nurses’ Health Study showed that invasive cancer developed in the ipsilateral breast in approximately two-thirds of patients.

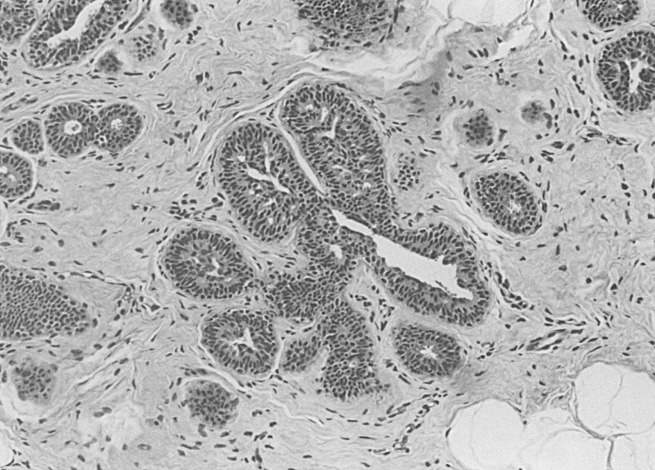

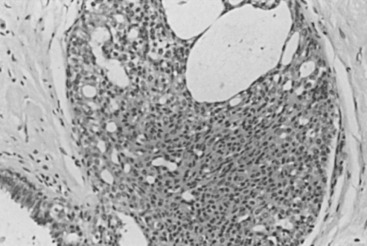

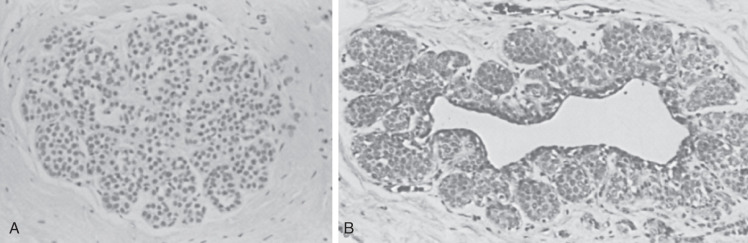

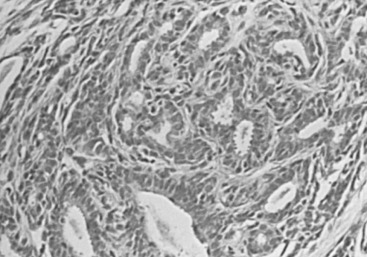

The philosophical underpinnings of the diagnostic term atypical ductal hyperplasia are the same as those for ALH. Thus the same features present in the analogous carcinoma in situ lesion are evident but in a less developed form. Because the criteria of ADH are derived from those of DCIS, histologic criteria for the latter must be followed (see Chapter 9 ). Two major criteria are required for the diagnosis of DCIS (low grade, noncomedo). First, a uniform population of neoplastic cells must populate the entire basement membrane–bound space. Furthermore, this alteration must involve at least two adjacent spaces ( Figs. 8.9 and 8.10 ). An adjunct to assessing the extent of involvement has been put forth by Tavassoli and Norris. They consider lesions smaller than 2 or 3 mm as ADH, with a resulting moderate increase in later cancer development. In addition to extent, an intercellular pattern of rigid arches and even placement of cells must be uniformly present. A helpful secondary criterion is hyperchromatic nuclei, which may not be present in all cases. The pattern of comedo DCIS is not discussed here because its characteristic extreme nuclear atypia is far beyond the patterns seen in ADH. Without the uniform application of criteria, consistency in diagnosis is unlikely ; however, when standardized criteria are applied, concordance is most often ensured.

Some cases of ADH share features with the so-called clinging carcinoma described by Azzopardi and coworkers. A study from northern Italy indicates a considerable overlap of clinging carcinoma with ADH in histologic patterns and in risk of subsequent cancer development. Many experts do not believe that the diagnosis of clinging carcinoma as a form of DCIS is appropriate because it obviously indicates a different behavior from that expected of widely accepted forms of DCIS (see Chapter 9 ).

Localized Sclerosing Lesions

The classic example of localized sclerosing lesions is sclerosing adenosis (SA), which has long been accepted as a gross and histologic mimicker of invasive carcinoma. It is in that capacity that it still has its greatest utility as a recognized diagnostic term and histologic pattern in the armamentarium of histopathologists. In its most usual form, SA is present as a microscopic lesion, probably unrecognized in both clinical and gross examination of tissues. SA is diagnosed only when a clearly lobulocentric change gives rise to enlargement and distortion of lobular units with a combination of increased numbers of acinar structures and a coexistent fibrous alteration ( Fig. 8.11 ). The normal two-cell population is maintained above the basement membrane in most areas, and the glandular units are regularly deformed.

Enlarged lobular units that appear otherwise normal or with slight gland deformity may not be recognized as SA but instead be diagnosed using the noncommittal and appropriately descriptive term adenosis. A palpable mass may be created by aggregations of microscopic foci of SA (aggregate adenosis). This situation has been termed adenosis tumor to indicate that a clinically palpable tumor may be produced. SA also commonly contains foci of microcalcification and, when present in this aggregate form, may be detectable with mammography.

There is a favored association of SA with ALH. Diagnostic patterns of ALH are usually present in nonsclerosed lobules elsewhere in the biopsy and are certainly difficult to recognize when present within a focus of SA. This may be because of the maintenance of relatively small spaces within readily identifiable lesions of SA (see discussion of ALH). The cytologic features of apocrine change may also be seen in adenosis, so-called apocrine adenosis. The enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli of apocrine cells, when present in a deformed, sclerotic lesion, can occasionally mimic invasive carcinoma. Some have used the appellation atypical to describe this setting. Atypical apocrine adenosis does not appear to be associated with an increased risk for the subsequent of breast carcinoma.

The differential diagnosis of these lesions includes tubular carcinoma and its variants. Usually, careful attention to the fact that SA is lobulocentric will suffice to correctly identify it. It is also true in SA that adjacent tubules tend to take approximately the same or similar shape as their immediate neighbors, although minor variations become marked if one skips to several tubular structures away. Myoepithelial markers are generally retained in SA, although densely sclerotic foci with glandular atrophy may have reduced or absent myoepithelial cells. This is then a helpful but not an absolute criterion. The spaces of a tubular carcinoma tend to be open, occasionally producing an irregular extension of the cluster of cells at one edge, resembling a teardrop. The cells of an infiltrating tubular carcinoma usually are layered singly, and when they are multilayered, the cells appear similar (see Chapter 10 ).

A rare condition known as microglandular adenosis may also mimic tubular carcinoma. In this condition, irregular, nonlobulocentric, small glandular spaces are present in increased numbers and appear to dissect and infiltrate through both stroma and fat, and a clinically palpable mass of several centimeters in diameter may be produced, which may be irregularly demarcated from surrounding tissue. The importance of this rare lesion is its ability to mimic tubular carcinoma.

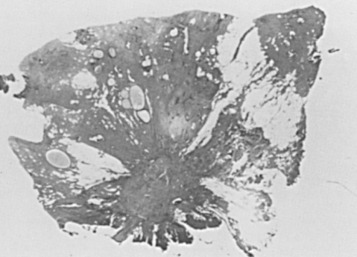

Radial Scar and Complex Sclerosing Lesions

Radial scar and complex sclerosing lesions have some similarities to SA: carcinoma may be mimicked clinically, histologically, or by breast imaging. Similar lesions were first described by Fenoglio and Lattes as mimickers of carcinoma. The lesions appear spiculated, hence the term radial scar . The lesions are not lobulocentric but evidently incorporate several deformed lobular units within their makeup, having as their probable origin a major stem of the duct system. This is particularly true of very large lesions. These are all characterized by a central scar from which elements radiate. The scar may vary through the full range of histologic appearances of the breast, including cystic dilation and units demonstrating hyperplasia and lobulocentric sclerosis, like that of SA. Myoepithelial markers may be reduced or lost in these sclerosing lesions. The microscopic features are determined by the degree of maturation; the classic appearance ( Fig. 8.12 ) represents the well-developed stage II. Lesions at an earlier stage show noticeable spindle cells and chronic inflammatory cells around the central parenchymal components, which are less distorted. The association of hyperplasia and cystic and apocrine change becomes more evident as the lesion matures.

The progressive nature of these lesions was studied ultrastructurally by Battersby and Anderson. A feature associated with early lesions was myofibroblasts in close proximity to degenerating parenchymal structures. Mature radial scars showed relatively few, sparsely distributed stromal myofibroblasts. Within the central scar, there are entrapped epithelial elements that mimic an invasive process ( Fig. 8.13 ). Although these are the elements that most commonly mimic carcinoma histologically, atypical hyperplastic lesions may be found within the preformed epithelial spaces in the outer portions of the lesion. The entrapped epithelial units may closely mimic tubular carcinoma, especially on core biopsy.