Chapter 42 Bartonellosis

BARTONELLA INFECTIONS

Clinical Presentation

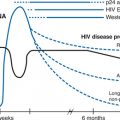

The spectrum of disease caused by Bartonella species includes cat scratch disease (B. henselae), bacillary angiomatosis (B. henselae and B. quintana), bacillary peliosis (B. henselae), endocarditis (B. henselae, B. quintana, and B. elizabethae), bacteremia (B. henselae, B. quintana, and B. vinsonii subsp arupensis), trench fever (B. quintana), meningitis/neuroretinitis (B. henselae, B. grahamii, and B. vinsonii subsp arupensis), Oroya fever (B. bacilliformis) and verruga peruana (B. bacilliformis).1,2 Bartonella infections occur in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, but some of the disease manifestations are related to the degree of immunocompromise (see Table 42-1). Cat scratch disease, a granulomatous lymphadenitis, usually occurs in immunocompetent individuals, or in patients early in the course of HIV infection. In contrast, bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis occur almost exclusively in severely immunocompromised individuals, especially in patients with late stage HIV infection (the median CD4 cell count in a series of patients with bacillary angiomatosis and peliosis was 22/mm3).3

Table 42-1 Manifestations of Bartonella Infection in HIV-Infected Patients

| Manifestation | Diagnostic Approach |

|---|---|

| Skin | |

| May resemble Kaposi sarcoma | Biopsy with W-S staining |

| Angiomatous nodule | |

| Friable vascular lesion | |

| Red papule | |

| Pedunculated lesion | |

| Deep subcutaneous mass | |

| Bone | |

| Extremely painful osteolysis | Biopsy with W-S staining |

| Lytic lesions on radiograph (technetium-positive) | |

| Lymph nodes | |

| Enlargement | Biopsy with W-S staining |

| Heart | |

| Valve vegetation | Echo, blood culture (lysis-centrifugation method or EDTA tube) |

| Valve insufficiency | |

| Blood | |

| Thrombosis, fever | Blood culture (echo to rule out endocarditis) |

| Liver/Spleen | |

| Hypodense lesions – CT | Biopsy with W-S staining (monitor for bleeding) |

| Hepatosplenomegaly – CT | |

| Elevated LFTs (alkaline phosphatase) | |

| Pancytopenia | |

| Thrombocytopenia | |

| Other | |

| Brain, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, others | Biopsy with W-S staining |

CT, computed tomography; echo, echocardiography; LFT, liver function tests; W-S, Warthin–Starry stain.

From Koehler JE. Bartonella-associated infections in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Clin Care 7:97, 1995. Copyright 1995, Massachusetts Medical Society.

Bacillary angiomatosis lesions are caused by infection with B. henselae or B. quintana.4,5 These lesions often are not recognized for several reasons: they can be impossible to distinguish clinically from Kaposi sarcoma lesions,6 and can have very diverse presentations.7 Bacillary angiomatosis has been described most frequently in skin (as angiomatous papules, pedunculated lesions or subcutaneous masses). These vascular proliferative lesions also occur in bone, the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, lymph nodes, and the central nervous system. A closely related angiomatous lesion of the liver and spleen is known as parenchymal bacillary peliosis8 and is caused by B. henselae.5

Some manifestations of Bartonella infection, including endocarditis, bacteremia or meningitis, occur in patients regardless of the degree of immunocompromise. In immunocompetent individuals, cat scratch disease is usually self-limited and the need for treatment of immunocompetent patients is controversial. In contrast, Bartonella infections occurring in HIV-infected patients are more severe and can even be fatal,9 and therefore all immunocompromised patients with Bartonella infection should be treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy.10

Taxonomy

Infections with Bartonella were first identified in the United States because of the AIDS epidemic. In 1983, Stoler et al identified an HIV-infected patient with subcutaneous lesions.11 They subsequently identified numerous bacilli within the lesions by electron microscopy, and treated the patient with erythromycin. The lesions resolved and little additional information became known about the causative organism until 1990, when bacterial DNA was extracted from biopsied bacillary angiomatosis tissue from HIV-infected and organ transplant patients. This molecular analysis led to identification of the organism as closely related to the agent of trench fever, Rochalimaea quintana.12 The new species also was isolated from the blood of HIV-infected patients,13 and subsequently was named R. henselae.14,15 This species was thought to be the sole agent of bacillary angiomatosis until the bacilli were isolated directly from cutaneous bacillary angiomatosis lesions, and R. quintana also was found to cause bacillary angiomatosis in immunocompromised patients.4

Brenner et al found that members of the Rochalimaea genus were very closely related to the sole species of the genus Bartonella, B. bacilliformis, and in 1993 all Rochalimaea species (R. henselae, R. quintana, R. elizabethae, and R. vinsonii) were merged into the Bartonella genus.16 Another genus, Grahamella, was subsequently merged with Bartonella, adding three more species to the genus, all of which infect small mammals: B. taylorii, B. grahamii, and B. doshiae.17 An additional eleven species were isolated from small mammals, including B. clarridgeiae, B. tribocorum, B. alsatica, B. koehlerae, B. birtlesii, B. bovis, B. capreoli, B. chomelii, B. schoenbuchensis, B. phoceensis, and B. rattimassiliensis. There are currently 19 extant species of Bartonella, five of which have been isolated from humans: B. bacilliformis, B. elizabethae, B. henselae, B. vinsonii subsp arupensis, and B. quintana. Only B. henselae and B. quintana have been associated with disease in HIV-infected patients.

Biology and Epidemiology

Before the bacillary angiomatosis bacillus was identified, epidemiological studies revealed that development of bacillary angiomatosis was statistically significantly associated with cat contact, cat scratches and cat bites.18 Further investigation of household cats belonging to four patients who developed bacillary angiomatosis revealed that all seven cats of these patients were bacteremic with B. henselae, the same species that caused the bacillary angiomatosis in these patients.19 Surveys of the cats in the greater San Francisco Bay area demonstrated that 41% of the 61 pet and pound cats were bacteremic with B. henselae, although no illness could be demonstrated in any of the infected cats.19

Because of this high prevalence of B. henselae bacteremia, and the demonstration that viable B. henselae could be cultured from cat fleas infesting bacteremic cats, the cat flea was suspected to be a vector of B. henselae. Further evidence implicating the cat flea as an arthropod vector of B. henselae was provided by the correlation between the increased prevalence of flea infestation and increased B. henselae seroprevalence in cats tested in different regions of the United States.20 Definitive demonstration of transmission of B. henselae from cat to cat was provided when fleas were combed from cats bacteremic with B. henselae and placed on specific pathogen free cats in an arthropod-free university facility. The recipient cats developed high level B. henselae bacteremia within 2 weeks of experimental infestation and seroconverted several weeks later.21

From the initial epidemiologic study in 1993,18 it was evident that although most of the patients had developed bacillary angiomatosis after traumatic cat contact, nearly one-third of the patients had no cat contact prior to developing bacillary angiomatosis. After the second species, B. quintana, was found to cause bacillary angiomatosis, it was suspected that these patients without cat contact might have developed bacillary angiomatosis infection caused by B. quintana. By determining the infecting species for 49 patients with bacillary angiomatosis and comparing exposures of these patients with their 96 matched controls, it was demonstrated that patients infected with B. henselae had a statistically significant association with cat contact including having received cat bites, cat scratches, and cat flea bites, as previously demonstrated.5 The patients with bacillary angiomatosis caused by B. quintana, however, had a statistically significant exposure to the body louse and were of lower socioeconomic status than their matched controls.5 This contemporary association between the body louse and B. quintana corroborates historical data demonstrating that the spread of B. quintana among the soldiers occurred via the body louse, causing an epidemic of trench fever affecting tens of thousands of troops in World War I.22

Each Bartonella species is believed to have one or more mammalian reservoir(s): the domestic cat for B. henselae, B. koehlerae, and B. clarridgeiae, the human for B. quintana and B. bacilliformis, rabbits for B. alsatica, cows for B. bovis, deer for B. capreoli and B. schoenbuchensis, and moles, voles, rats, and mice for B. vinsonii, B. taylorii, B. doshiae, B. grahamii, B. elizabethae, and B. tribocorum. Arthropod vectors of Bartonella species have not been studied as extensively as reservoirs, but in addition to the cat flea vector (Ctenocephalides felis) of B. henselae,21 another flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, transmitted Bartonella spp to voles.23 The sand fly Lutzomyia verrucarum is the natural arthropod vector known to transmit B. bacilliformis among humans in the Peruvian Andes,24 and little information is currently known about arthropod vectors of other Bartonella species.

Microbiology

Bartonella species are small, slowly growing, and very fastidious gram-negative rods. Five species have flagella and are motile, B. bacilliformis, B. clarridgeiae, B. chomelii, B. capreoli, and B. schoenbuchensis.25 The Bartonella bacilli are relatively inert biochemically and are not able to oxidize glucose. Bartonella species are able to utilize glutamate and succinate as carbon sources, and hemin or serum supplementation of growth media permits optimal growth on artificial media.26 The colony morphology of primary isolates differs for B. henselae (rough, with pitting of the agar) and B. quintana (smooth, without pitting of the agar).5

DIAGNOSIS

Direct Detection

Bartonella species can be detected in biopsied bacillary angiomatosis tissue using hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining and optimally, the Warthin–Starry silver stain (Table 42-2). For cutaneous bacillary angiomatosis lesions, a 5 mm punch biopsy specimen usually provides adequate tissue for diagnosis (for small papules or subcutaneous nodules). The vascular proliferative changes identified by H and E staining are usually very characteristic.27 Newly formed, capillary-sized blood vessels can be identified and are lined with protuberant endothelial cells. Adjacent to these regions of vascular proliferation are clusters of granular, amphophilic material that represent microcolonies of Bartonella bacteria; distinct bacilli are revealed in these granular deposits when the Warthin–Starry silver stain is used. In situ immunohistochemical staining also has been useful in direct visualization of Bartonella bacilli in biopsied tissue from bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis lesions.28

Table 42-2 Bartonella Laboratory Diagnosis

| Method | Comments |

|---|---|

| Histopathology | Check for (H&E staining) |

| Lobular, vascular proliferation | |

| Neutrophils and debris | |

| Basophilic granular material | |

| Protruberant endothelial cells | |

| Check for darkly staining bacilli (Warthin–Starry stain) | |

| Blood culture | Lysis-centrifugation or EDTA tubes, onto fresh chocolate and rabbit blood agars |

| Incubate in 5% CO2 at 35°C for 21 days | |

| Culture of tissue biopsy | Experimental |

| Co-cultivation of endothelial cells with homogenate | |

| Serology | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indirect immunofluorescence antibody test |

From Koehler JE: Bartonella-associated infections in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Clin Care 7:97, 1995. Copyright 1995, Massachusetts Medical Society.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree