Axillary Lymphadenectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Identification of Anatomical Structures for Level I and II Axillary Dissection

Removal of Level III Nodes

Removal of Rotter Nodes

Removal of a Sufficient Number of Lymph Nodes for Axillary Staging

Identification and Preservation of the Long Thoracic, Thoracodorsal, and Medial Pectoral Nerves

Identification and Preservation of the Second and Third Intercostobrachial Nerves

Drain Placement

1A. IDENTIFICATION OF ANATOMICAL STRUCTURES FOR LEVEL I AND II AXILLARY DISSECTION

Recommendation: Identification of the axillary vein and latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, serratus anterior, and subscapularis muscles is essential for the resection of sufficient level I and II axillary nodes for breast cancer staging and adjuvant treatment planning.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Strength of Recommendation: The consensus of the group supports this guideline based on historic evidence.

Rationale

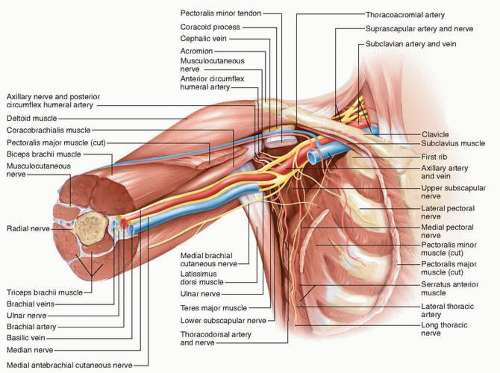

Breast cancer typically spreads to the axillary lymph nodes first, and axillary dissection is important for both local control and treatment planning. The anatomic borders of the axilla must be identified to adequately resect level I and II axillary lymph nodes (see Fig. 3-1). The axilla is a triangular space that is delineated by the axillary vein

superiorly, the latissimus dorsi muscle laterally, the serratus anterior muscle medially, the subscapularis muscle posteriorly, and the pectoralis minor and major muscles anteriorly. Lymph nodes in the axilla are identified by their location in one of three anatomical levels. Level I contains the axillary lymph nodes between the latissimus dorsi and the lateral border of the pectoralis minor muscle; level II contains the axillary lymph nodes between the lateral and medial borders of the pectoralis minor muscle; and level III encompasses the lymph nodes between the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle and Halsted’s ligament. Level III axillary nodes can be exposed by resecting or dividing the pectoralis minor muscle. Axillary lymph nodes are located primarily in level I (60% to 70% of nodes), followed by level II (20% to 30%) and level III (10% to 20%).1,2,3 Axillary metastases are most often identified in level I nodes followed by level II nodes. Single-node metastasis occurs in level I nodes almost exclusively.1,2 Metastases that occur in level II or III nodes in the absence of level I metastasis (“skip” metastases) are rare and typically occur in level II nodes.2,4

superiorly, the latissimus dorsi muscle laterally, the serratus anterior muscle medially, the subscapularis muscle posteriorly, and the pectoralis minor and major muscles anteriorly. Lymph nodes in the axilla are identified by their location in one of three anatomical levels. Level I contains the axillary lymph nodes between the latissimus dorsi and the lateral border of the pectoralis minor muscle; level II contains the axillary lymph nodes between the lateral and medial borders of the pectoralis minor muscle; and level III encompasses the lymph nodes between the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle and Halsted’s ligament. Level III axillary nodes can be exposed by resecting or dividing the pectoralis minor muscle. Axillary lymph nodes are located primarily in level I (60% to 70% of nodes), followed by level II (20% to 30%) and level III (10% to 20%).1,2,3 Axillary metastases are most often identified in level I nodes followed by level II nodes. Single-node metastasis occurs in level I nodes almost exclusively.1,2 Metastases that occur in level II or III nodes in the absence of level I metastasis (“skip” metastases) are rare and typically occur in level II nodes.2,4

1B. REMOVAL OF LEVEL III NODES

Recommendation: The removal of level III axillary nodes is not typically indicated for patients with stage I or II breast cancer but should be considered to facilitate local disease control in patients with locally advanced breast cancer or N2 disease and patients in whom the nodes are identified by palpation intraoperatively.

Type of Data: Randomized controlled trials.

Strength of Recommendation: There is strong evidence to support this recommendation.

Rationale

Level III nodes account for less than 20% of axillary lymph nodes and are the least likely to have metastases.1 Skip metastases in level III nodes occur in less than 1% of patients.4 Two randomized controlled trials enrolling primarily patients with stage I or II disease revealed no differences in breast cancer staging or disease-free or overall survival rates between patients who underwent level I and II axillary dissection and those who underwent level I, II, and III axillary dissection after 10 years of follow-up. However, the patients who underwent level I, II, and III dissection had significantly longer operative times and more blood loss than patients who underwent level I and II dissection.5,6 In patients with T3 breast cancer, who have a 32% risk of having positive nodes in all three levels, resection of level III nodes is reasonable if level I or II nodes are positive. Furthermore, in patients with more than four positive level I nodes, who have a >60% likelihood of level II and III metastases,3 level III nodes can be resected to facilitate local control if clinically suspicious nodes are identified by digital palpation.7

1C. REMOVAL OF ROTTER NODES

Recommendation: The removal of Rotter nodes (i.e., the interpectoral nodes) is not typically recommended for patients with stage I or II breast cancer but should be considered to facilitate locoregional disease control in patients with locally advanced breast cancer or N2 disease and in patients for whom preoperative imaging studies reveal the nodes to be suspicious.

Type of Data: Case studies, retrospective reviews.

Strength of Recommendation: There is only retrospective data to support this recommendation. The consensus is that the risk of routine resection of asymptomatic Rotter nodes outweighs the small potential benefit.

Rationale

Rotter nodes were once routinely removed as part of radical mastectomy, which included the resection of the pectoralis major and minor muscles. Following the adoption of modified radical mastectomy, which included the dissection of level I and II lymph nodes but not the resection of the pectoralis major and minor muscles, several retrospective studies evaluated the clinical significance of Rotter nodes. These studies assessed the number of Rotter nodes that were positive for metastatic carcinoma, the tumor characteristics associated with positive Rotter nodes, and the frequency with which Rotter nodes were identified as the only positive nodes.8,9,10,11,12 Positive Rotter nodes were more frequently identified in patients who had tumors in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, T3 disease, and/or positive axillary lymph nodes.10 In case

series, the incidence of isolated positive Rotter nodes was 0.3% among patients with stage I or II invasive breast cancer8 but as high as 13% among patients with stage III disease, who comprised 50% of the cohort.9

series, the incidence of isolated positive Rotter nodes was 0.3% among patients with stage I or II invasive breast cancer8 but as high as 13% among patients with stage III disease, who comprised 50% of the cohort.9

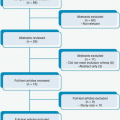

2. REMOVAL OF A SUFFICIENT NUMBER OF LYMPH NODES FOR STAGING

Recommendation: A target minimum of 10 axillary lymph nodes should be removed to ensure a high level of confidence that the remaining lymph nodes are negative.

Type of Data: Several well-designed, nonrandomized controlled trials.

Strength of Recommendation: There is moderate evidence to support this recommendation.

Rationale

Before Chemotherapy

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) provides important prognostic information that can affect treatment decisions. The primary role of ALND is to provide a means of accurately staging breast cancer. ALND can also affect recurrence risk.

ALND primarily includes the resection of level I and II axillary lymph nodes. Fineneedle aspiration (FNA) can be performed to identify metastatic disease in level III nodes or Rotter nodes that positron emission tomography/computed tomography or infraclavicular ultrasonography reveal to be suspicious for disease involvement. Level III nodes or Rotter nodes that have biopsy-proven metastasis should be removed along with the level I and II nodes. Level I and II ALND should include tissue inferior to the axillary vein as well as tissue lateral to the latissimus dorsi muscle and medial to the pectoralis minor muscle.

Studies reviewing lymph node status and treatment outcomes in patients undergoing ALND have shown that a sample size of a minimum of 10 lymph nodes is needed to provide sufficient information to make sound treatment decisions in breast cancer patients.13 Given the current practice of sentinel node biopsy for axillary staging in most breast cancer patients, an axillary dissection is now reserved as more of a therapeutic rather than diagnostic operation. The emphasis now is to use anatomical landmarks to guide therapeutic dissection of the axilla without concentration on number of nodes removed in order to provide sufficient local control for the axilla.

After Chemotherapy

The surgical techniques that guide axillary dissection are the same regardless of whether ALND is performed before or after chemotherapy. In both instances, the area of dissection is the same, and therapeutic dissection using anatomical landmarks is performed to clear the axillary nodes to provide local control of potential regional disease.

In contrast to patients undergoing surgery prior to any systemic treatment, some studies have shown that fewer lymph nodes are retrieved following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.14 However, other investigations have found that axillary dissections

performed before chemotherapy and axillary dissections performed after chemotherapy yield similar numbers of lymph nodes.15,16 Therefore, adequate axillary node dissection after chemotherapy should include level I and II lymph nodes within the previously outlined boundaries rather than the absolute node count.

performed before chemotherapy and axillary dissections performed after chemotherapy yield similar numbers of lymph nodes.15,16 Therefore, adequate axillary node dissection after chemotherapy should include level I and II lymph nodes within the previously outlined boundaries rather than the absolute node count.

3A. IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE LONG THORACIC, THORACODORSAL, AND MEDIAL PECTORAL NERVES

Recommendation: Complete axillary dissection should include the identification and preservation of the long thoracic, thoracodorsal, and medial pectoral nerves. The nodal tissue should be dissected from these nerves with minimal nerve manipulation and without skeletonization to ensure adequate oncologic resection with minimal nerve morbidity. The nodal contents between the long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves should be dissected to achieve optimal axillary nodal clearance.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Strength of Recommendation: Although the data is retrospective, there is strong consensus of the panel to follow this recommendation based on historical evidence and to limit patient morbidity.

Rationale

A major detraction from routine use of ALND is the increased morbidity and sequelae from nerve injury, which is a major complaint of breast cancer survivors. Nerve injury can cause muscle weakness or pain, limit movement, and result in anatomical abnormalities. Thus, the preservation of the main nerves in the axilla is necessary to help ensure optimal physical outcomes. The long thoracic nerve, which innervates the serratus anterior muscle, originates from the cervical nerve roots and travels within a fatty layer along the muscle surface. However, its exact anatomy varies among patients. Intentional or inadvertent transection of the nerve results in serratus muscle palsy that manifests as pain, weakness, limited shoulder elevation, and scapular winging.17 Additional surgery and/or years of therapy may be necessary to recover function that is lost as a result of transecting the nerve.18,19

The thoracodorsal nerve, which innervates the latissimus dorsi muscle, arises primarily from the C7 and C8 cervical nerve roots and descends behind the axillary vein before joining with the thoracodorsal artery and vein to form the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle. Although contemporary practice favors preserving the thoracodorsal nerve, this nerve can be resected if the nerve is encased by tumor. However, resecting the nerve is rarely necessary given the widespread use of systemic neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Transection of the thoracodorsal nerve results in weakness or atrophy of the latissimus dorsi muscle.

A complete ALND should include resection of the tissue between the long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves. Retrospective studies have reported that nodal tissue anterior to the subscapularis muscle in this area is present in 56% to 67% of patients and that 10% of these nodes are positive.20,21

The medial pectoral nerve, which innervates the lower parts of the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles, arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and is located lateral to the lateral pectoral nerve.22 Transection of this nerve causes weakness and atrophy of the pectoralis minor muscle and the lateral and inferior portions of the pectoralis major muscle and results in muscle fibrosis. The nerve can be divided in cases of dense tumor involvement.

3B. IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE SECOND AND THIRD INTERCOSTOBRACHIAL NERVES

Recommendation: The axilla should be carefully dissected to identify and preserve the intercostobrachial nerves (ICBNs). In the level I axilla, these nerves exit the chest wall through the intercostal and serratus anterior muscles and cross the axilla parallel to the axillary vessels. The second ICBN, which provides sensation to the skin of the medial and posterior upper arm, is generally the largest and most superior of the ICBNs. Unless the nerve is encased by tumor, this nerve should be spared by dissecting it from the axillary fat. Once released, the nerve is positioned inferior to the axillary vein.

Type of Data: Small prospective trials and a larger retrospective dataset.

Strength of Recommendation: There is moderate evidence to support this recommendation.

Rationale

Four small prospective trials with follow-up durations ranging from 3 to 38 months have investigated the value of ICBN preservation by randomizing patients to ALND with ICBN preservation or ALND without ICBN preservation. These trials, each of which enrolled fewer than 130 patients, revealed no significant difference in the rates of survival or axillary disease recurrence between patients who did and patients who did not have ICBN preservation. However, whereas Freeman et al,23 Abdullah et al,24 and Torresan et al25 found that patients with ICBN preservation had significantly fewer sensory deficits and symptoms than patients with no ICBN preservation, Salmon et al26 found that ICBN preservation provided no functional advantage. Findings from a retrospective study with a larger patient cohort and longer follow-up suggest that ligating or damaging the ICBNs during axillary surgery exacerbates sensory changes in the arm that may persist for years.27

4. DRAIN PLACEMENT

Recommendation: Optimal drain placement following standard level I, II, and/or III ALND is essential to preventing seroma in order to avoid delays to adjuvant treatment.

Type of Data: Multiple randomized trials and two meta-analyses.

Strength of Recommendation: There is strong evidence to support this recommendation.

Rationale

One of the most common complications of ALND is seroma. Seromas or subcutaneous fluid collections are often painful for patients and can increase infectious complications. Persistent seroma can lead to mild or severe infections and/or delays in adjuvant therapy, thus potentially affecting oncologic outcomes. Two meta-analyses have systematically reviewed nine randomized controlled trials that compared the outcomes of patients who underwent ALND with drainage to those of patients who underwent ALND with no or short-term drainage.28,29 The numbers of patients included in each of these trials ranged from 40 to 227; more than 950 patients total were included.28,29 Compared with patients who had no or only short-term drainage, patients who had volume-controlled axillary drainage (in whom drain removal was performed only after fluid volumes decreased to <30 to <50 mL/day) were significantly less likely to develop clinically significant seroma. Patients with drains had significantly fewer seromas, fewer aspirations, and smaller aspiration volumes. Overall, these findings were consistent regardless of whether ALND was performed with segmental resection or mastectomy. Although multiple studies have compared the different techniques and instruments or devices used for ALND, as well as the use of different pharmacologic agents to potentially decrease drainage following ALND,30 comparisons of these studies and their patient cohorts are hindered by potential differences in techniques, drain usage, drain removal criteria, and extent of disease and axillary dissection.

REFERENCES

1. Berg JW. The significance of axillary node levels in the study of breast carcinoma. Cancer 1955;8(4):776-778.

2. Veronesi U, Luini A, Galimberti V, et al. Extent of metastatic axillary involvement in 1446 cases of breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 1990;16(2):127-133.

3. Veronesi U, Rilke F, Luini A, et al. Distribution of axillary node metastases by level of invasion. An analysis of 539 cases. Cancer 1987;59(4):682-687.

4. Boova RS, Bonanni R, Rosato FE. Patterns of axillary nodal involvement in breast cancer. Predictability of level one dissection. Ann Surg 1982;196(6):642-644.

5. Tominaga T, Takashima S, Danno M. Randomized clinical trial comparing level II and level III axillary node dissection in addition to mastectomy for breast cancer. Br J Surg 2004;91(1): 38-43.

6. Kodama H, Nio Y, Iguchi C, et al. Ten-year follow-up results of a randomised controlled study comparing level-I vs level-III axillary lymph node dissection for primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95(7):811-816.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree