Total Mastectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Incision Placement

Boundaries of Mastectomy

Mastectomy Flap Elevation

Excision of the Pectoralis Major Muscle

Prevention of Seroma/Drain Placement

1. INCISION PLACEMENT

Recommendation: Incisions for total mastectomy should be placed to facilitate the removal of the preponderance of breast tissue to achieve local disease control and decrease the risk of recurrent breast cancer.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Strength of Recommendation: The consensus of the group supports this guideline based on historic evidence.

Rationale

Incision placement for total mastectomy is dictated by whether immediate reconstruction of the affected breast will be performed. The type of total mastectomy planned—simple total mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, or nipple-sparing mastectomy—also guides incision placement.

Mastectomy without Immediate Breast Reconstruction

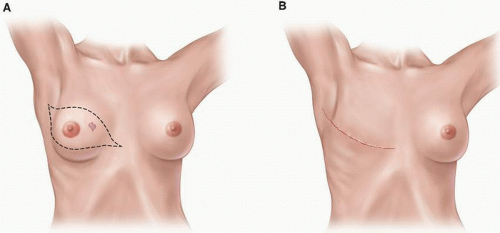

In patients not undergoing immediate breast reconstruction, a simple total mastectomy is performed. In these cases, an elliptical incision that encompasses the nipple-areola complex (NAC) and removes enough skin to achieve a smooth, even chest wall

without tension or redundant skin (“dog ears”) is made (Fig. 2-1). Although no strong data support the excision of percutaneous core biopsy scars not incorporated within the planned mastectomy incision, the general consensus is that any scar resulting from previous open biopsy or lumpectomy should be removed at the time of mastectomy, ideally within the ellipse of removed skin. The removal of a remote scar caused by previous open biopsy or lumpectomy may necessitate a separate incision.

without tension or redundant skin (“dog ears”) is made (Fig. 2-1). Although no strong data support the excision of percutaneous core biopsy scars not incorporated within the planned mastectomy incision, the general consensus is that any scar resulting from previous open biopsy or lumpectomy should be removed at the time of mastectomy, ideally within the ellipse of removed skin. The removal of a remote scar caused by previous open biopsy or lumpectomy may necessitate a separate incision.

Special consideration must be given to patients with inflammatory breast cancer. These patients have a very high rate of local disease recurrence. They are most successfully treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by a modified radical mastectomy (i.e., a simple total mastectomy plus axillary lymph node dissection) and subsequently adjuvant therapy with irradiation of the chest wall and regional lymphatics. Modified radical mastectomy involves the resection of all involved skin, confirmation of negative surgical margins, and closure resulting in a flat chest wall without redundancy to facilitate the delivery of adjuvant radiotherapy. Any skin with evidence of residual disease following neoadjuvant chemotherapy must be resected to negative margins. A similar incision is made for modified radical mastectomies as total or simple mastectomies; however, for modified radical mastectomies, the surgeon may extend the incision more laterally to get a complete exposure of the axillary nodes. In simple mastectomies, many surgeons will have a small separate axillary incision for the sentinel node biopsy.

Mastectomy with Immediate Breast Reconstruction

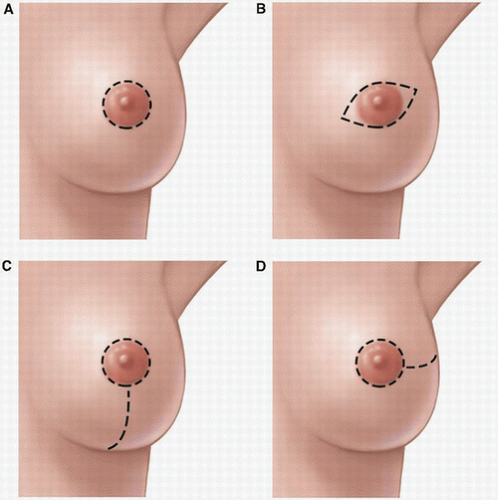

Compared with mastectomy without immediate breast reconstruction, mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction has more options for incision placement. In patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction, a skin-sparing mastectomy is performed, and the surgical oncologist and reconstructive surgeon must work together to plan the mastectomy incision(s). In the case of a small or moderately sized breast,

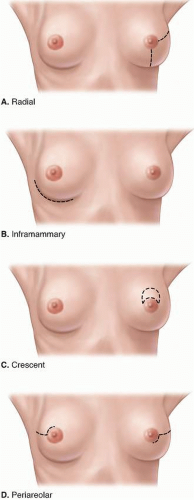

a circular incision around the edge of the areola with or without lateral extension is employed for skin-sparing mastectomy (Fig. 2-2). In the case of a large breast or mild or moderate breast ptosis, the volume of the skin envelope must be reduced, and this can be achieved by increasing the size of a central elliptical incision or by using a reduction pattern incision according to the plastic surgeon’s preference (see Fig. 2-2).

a circular incision around the edge of the areola with or without lateral extension is employed for skin-sparing mastectomy (Fig. 2-2). In the case of a large breast or mild or moderate breast ptosis, the volume of the skin envelope must be reduced, and this can be achieved by increasing the size of a central elliptical incision or by using a reduction pattern incision according to the plastic surgeon’s preference (see Fig. 2-2).

FIGURE 2-2 Incisions for skin-sparing mastectomy. A: Round periareolar, (B) small elliptical periareolar, (C) perioareolar with inferior extension, (D) perioareolar with lateral extension. |

Nipple-sparing mastectomy, a type of skin-sparing mastectomy that preserves not only the breast skin but also the NAC, may also be employed in patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction (Fig. 2-3). For best results, in nipple-sparing mastectomy, a periareolar incision not exceeding 30% of the circumference of the areola can be used. Incisions that encircle the areola should be avoided, as incisions exceeding 30% of the areolar circumference increase the risk of nipple necrosis.1 Other incisions associated with a low risk of nipple necrosis include the inframammary fold incision and the radial incisions (see Fig. 2-3). The crescent incision is often utilized in women with breast ptosis, as it allows the surgeon good exposure and lifts the NAC to a more cosmetically appropriate position (see Fig. 2-3). At the time of nipple-sparing mastectomy, the mastectomy incision or a separate axillary incision can be accessed to perform nodal staging with either sentinel lymph node surgery or axillary lymph node dissection.

2. BOUNDARIES OF MASTECTOMY

Recommendation: Although the options for incisions and the amount of skin excised for simple total mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, and nipple-sparing mastectomy vary, the anatomical boundaries guiding mastectomy remain uniform in order to remove the entire breast parenchyma.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Strength of Recommendation: The consensus of the group supports this guideline based on historic evidence.

Rationale

The boundaries of the breast include the second rib superiorly, the upper border of the rectus sheath inferiorly, the lateral border of the sternum medially, and the latissimus dorsi muscle laterally.2 The superior lateral boundary of any mastectomy should include the tail of the breast, which extends into the axilla a variable distance beyond the lateral margin of the pectoralis major muscle. Care should be taken to remove any glandular breast tissue that extends into the axilla. The breast should be dissected off the underlying pectoralis major muscle. Removal of the pectoral fascia with the breast is commonly but not uniformly advised. The fascia overlying the serratus anterior muscle and the rectus sheath should be preserved. Sutures should be placed to provide specimen orientation. Most mastectomies remove more than 95% of the breast; some breast tissue invariably remains. Thus, new primary cancers can, although rarely do, occur even after mastectomy. Therefore, meticulous resection and thorough removal of the breast tissue is essential to achieving optimal outcomes.

3. MASTECTOMY FLAP ELEVATION

Recommendation: Mastectomy flaps should be elevated in a manner that facilitates the removal of essentially all breast tissue to reduce the risk of recurrence and that preserves the overlying subcutaneous tissue and its vascular plexus to minimize the risk of flap necrosis.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Strength of Recommendation: The consensus of the group supports this guideline based on historic evidence.

Rationale

Mastectomy flap thickness varies greatly among patients; the subcutaneous layer in thin patients may be only 2 to 3 mm thick. Persistent glandular tissue and residual disease have been reported to be more prevalent in patients with mastectomy flaps thicker than 5 mm.3 Anatomic studies have confirmed the interdigitation of the subcutaneous fat and the underlying glandular portion of the breast. Because the border between the subcutaneous tissue and the breast may be poorly defined in patients with excessive adipose tissue in the breast, care must be taken to not extend mastectomy flaps into the

deeper glandular plane and thus leave breast tissue in the mastectomy flap.4 Thin mastectomy flaps dissected at the level of the dermis are predisposed to necrosis, whereas thick mastectomy flaps may include residual breast tissue that increases the risk of recurrence. Meticulous flap elevation is especially important in cases of skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, in which the smaller incision may limit visualization of the upper and lateral borders of dissection depending on which incision is used. All margins at the site of known malignancy should be examined grossly and pathologic analysis of frozen sections performed as indicated to ensure that clear surgical margins are obtained. For patients in whom mammography has revealed diffuse microcalcifications, mammography of the mastectomy specimen with serial sections may be considered; if microcalcifications near a superficial margin are observed, additional skin or subcutaneous tissues can be excised at that site to obtain an adequate final margin.5 In cases in which the tumor is close to the dermis, a negative margin of skin directly overlying the tumor must be achieved, or the skin must be excised.

deeper glandular plane and thus leave breast tissue in the mastectomy flap.4 Thin mastectomy flaps dissected at the level of the dermis are predisposed to necrosis, whereas thick mastectomy flaps may include residual breast tissue that increases the risk of recurrence. Meticulous flap elevation is especially important in cases of skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, in which the smaller incision may limit visualization of the upper and lateral borders of dissection depending on which incision is used. All margins at the site of known malignancy should be examined grossly and pathologic analysis of frozen sections performed as indicated to ensure that clear surgical margins are obtained. For patients in whom mammography has revealed diffuse microcalcifications, mammography of the mastectomy specimen with serial sections may be considered; if microcalcifications near a superficial margin are observed, additional skin or subcutaneous tissues can be excised at that site to obtain an adequate final margin.5 In cases in which the tumor is close to the dermis, a negative margin of skin directly overlying the tumor must be achieved, or the skin must be excised.

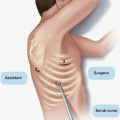

Technical Considerations for Flap Elevation

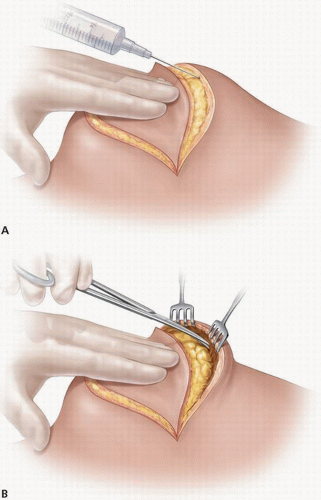

Mastectomy flaps were historically developed using sharp dissection with a scalpel or scissors. Sharp dissection as the primary method of flap elevation for most surgeons was eventually replaced by electrocautery, which resulted in significantly less blood loss (Fig. 2-4).6 Now, low-energy dissection devices provide an alternative to both sharp dissection and electrocautery for flap elevation. These devices generate temperatures that seal vascular and lymphatic structures, and they divide tissue with less collateral tissue injury and lower seroma volumes compared with sharp dissection or electrocautery.7,8 To date, however, no specific device has been associated with better oncologic outcomes.

One optional adjunct to flap elevation with sharp dissection is tumescent solution injection, which has been reported to reduce operating room time without the blood loss or thermal injury associated with sharp dissection or electrocautery alone.9 The tumescent solution is composed of normal saline, lidocaine, and epinephrine. After skin incision, a 20-gauge spinal needle is used to inject the solution into the space between the subcutaneous and glandular tissue to develop a bloodless plane (see Fig. 2-4). The blades of the scissors are opened approximately 1 to 1.5 cm and the scissors are pushed through the developed plane tissue to elevate the flap.10 Although many breast surgeons have adopted this technique, some groups have reported that tumescent solution injection results in higher rates of flap necrosis than electrocautery does, possibly owing to the vasoconstriction it causes.10,11,12 Surgeons should select the technique that they are confident will enable them to completely remove the breast with the fewest associated complications.

4. EXCISION OF THE PECTORALIS MAJOR MUSCLE

Recommendation: Although neoadjuvant systemic therapy should minimize the amount of direct muscle invasion encountered during mastectomy, localized excision of the pectoralis major muscle is sometimes necessary to achieve clear margins.

Type of Data: Older prospective trials and more recent case series.

FIGURE 2-4 Flap elevation done sharply after injection of tumescent solution. Part A shows injection of tumescent solution with spinal needle and part B shows flap elevation with scissors. |

Strength of Recommendation: The consensus of the group supports this guideline based on historic evidence.

Rationale

Resection of the pectoral muscle, an element of the classic Halstead radical mastectomy described in 1894,13 was routinely performed during mastectomy for more than 70 years. However, the clinical benefit of such radical surgery was questioned once effective adjuvant radiotherapy and systemic therapies came into use. In 1978,

Baker et al found no difference between the 5-year survival rates of 144 breast cancer patients who underwent radical mastectomy and 188 patients who underwent mastectomy without removal of the pectoralis major muscle at the discretion of the operating surgeon.11 Although radical mastectomy did not result in lower local recurrence rates among patients with stage I or II breast cancer, it did appear to result in lower recurrence rates among patients with stage III disease. On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that compared with mastectomy without removal of the pectoralis major muscle, radical mastectomy provided a better chance of local control but not survival in patients with stage III breast cancer. The results of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-04 trial, first published in 1977 and most recently updated with 25-year follow-up data in 2002,12 demonstrated that there was no significant difference in rates of overall survival or local control in patients who underwent total mastectomy with postmastectomy radiation (PMRT) compared to patients who had radical mastectomy. Local control was inferior in patients with positive nodes without radiation. As a result of this study, the routine en bloc resection of uninvolved pectoralis major muscles was abandoned. However, removal of the pectoralis major muscle during mastectomy may be indicated in those patients with diffuse pectoral muscle involvement at diagnosis.

Baker et al found no difference between the 5-year survival rates of 144 breast cancer patients who underwent radical mastectomy and 188 patients who underwent mastectomy without removal of the pectoralis major muscle at the discretion of the operating surgeon.11 Although radical mastectomy did not result in lower local recurrence rates among patients with stage I or II breast cancer, it did appear to result in lower recurrence rates among patients with stage III disease. On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that compared with mastectomy without removal of the pectoralis major muscle, radical mastectomy provided a better chance of local control but not survival in patients with stage III breast cancer. The results of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-04 trial, first published in 1977 and most recently updated with 25-year follow-up data in 2002,12 demonstrated that there was no significant difference in rates of overall survival or local control in patients who underwent total mastectomy with postmastectomy radiation (PMRT) compared to patients who had radical mastectomy. Local control was inferior in patients with positive nodes without radiation. As a result of this study, the routine en bloc resection of uninvolved pectoralis major muscles was abandoned. However, removal of the pectoralis major muscle during mastectomy may be indicated in those patients with diffuse pectoral muscle involvement at diagnosis.

Removal of the pectoralis major muscle during mastectomy may be indicated in some patients who present with focal or a large area of muscle involvement. Most patients presenting with focal muscle invasion have stage III, locally advanced cancers and should receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormonal therapy to facilitate obtaining clear margins at surgery. In patients whose tumors have limited response to neoadjuvant therapy, muscle excision may have a limited treatment role; it may also have clinical benefit in patients who have local recurrences that are refractory to treatment.14 In these patients, resection of the pectoralis major muscle at the site of focal invasion to obtain negative margins for improved local control seems prudent. The only aim of this resection should be to achieve a clear margin, and this rarely requires the removal of a large portion of the muscle. In most patients with focal tumor involvement of the pectoralis major muscle, a combination of resection of the area of involved pectoralis muscle plus PMRT are recommended.

Muscle invasion or T4 disease is considered a definite indication for PMRT in patients undergoing mastectomy. Several authors have demonstrated that in the absence of PMRT, close or positive margins and invasion of the pectoralis major muscle or its fascia increase the risk of local recurrence. For example, researchers in the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82B and C trials studied a group of more than 1,500 high-risk patients who received no radiation and found that fascial invasion was an independent predictor of locoregional recurrence.14 Similarly, a group from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reported that in high-risk patients who did not receive PMRT, positive margins and fascial invasion were significant predictors of locoregional recurrence.15 A systematic review confirmed that muscle or fascial invasion increased the relative risk for local recurrence (relative risk, 1.7) in patients who did not receive PMRT.16 Although excision of focal muscular

involvement followed by PMRT is often used to achieve clear margins, strong data supporting the benefit of muscle excision in this setting are lacking.

involvement followed by PMRT is often used to achieve clear margins, strong data supporting the benefit of muscle excision in this setting are lacking.

5. PREVENTION OF SEROMA/DRAIN PLACEMENT

Recommendation: Drains must be optimally placed to prevent seroma formation and reduce seroma-related morbidity after total mastectomy in order to avoid delays to adjuvant treatment.

Type of Data: Small prospective and multiple retrospective trials.

Strength of Recommendation: The group strongly recommends drain placement to limit seroma formation which could delay adjuvant treatment.

Rationale

Drains are placed at the completion of total mastectomy to evacuate fluid from the surgical site and prevent seroma formation. Seromas form from the inflammatory reaction to the surgical trauma. Electrocautery, which is widely used for mastectomy flap elevation, has been shown to exacerbate the inflammatory processes that lead to seroma formation.17,18 With the exception of a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2, which is associated with prolonged seroma drainage,19 no patient-, procedure-, or tumor-related factors have been found to affect seroma extent or duration. In patients at high risk of persistent seroma following total mastectomy, closure of the dead space with sutures and/or tissue sealants may be considered; however, this approach offers limited benefit in patients undergoing uncomplicated simple total mastectomy that does not include extensive axillary node dissection.

Persistent seroma can lead to mild or severe infections and/or delays in adjuvant therapy, thus potentially affecting oncologic outcomes.20,21 The most widespread approach to reducing seroma-related morbidity after mastectomy is the use of closedsuction drainage. Small prospective trials have shown no difference in benefit between the use of multiple drains and a single drain21,22,23 or between the use of low-pressure and high-pressure suction.24 At least one closed suction drain should be placed at the time of wound closure; this drain should extend across the pectoralis major muscle towards the axillary space. Data from one randomized controlled trial supports placing a chlorhexidine disc at the drain site and using antiseptic bulb irrigation to reduce drain colonization.25

Various strategies have been employed to limit seroma formation without drain placement. For example, prospective trials have shown that fibrin sealant reduces the duration and quantity of wound drainage in patients undergoing total mastectomy and concomitant axillary node dissection.26,27 Fixation of the flap with sutures may also result in earlier drain removal, although this approach is not widely used.28,29 In most settings, removing the drain only after an output of <30 mL/day has achieved results in optimal outcomes.30 Early drain removal without consideration of drainage volume is not recommended because it has been associated with a higher rate of postoperative complications.28

REFERENCES

1. Kuerer HM, ed. Kuerer’s Breast Surgical Oncology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010.

2. Garwood ER, Moore D, Ewing C, et al. Total skin-sparing mastectomy: complications and local recurrence rates in 2 cohorts of patients. Ann Surg 2009;249:26-32.

3. Harris JR, Lippman ME, Osborne CK, et al. Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

4. Torresan RZ, dos Santos CC, Okamura H, et al. Evaluation of residual glandular tissue after skin-sparing mastectomies. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:1037-1044.

5. Nickell WB, Skelton J. Breast fat and fallacies: more than 100 years of anatomical fantasy. J Hum Lact 2005;21:126-130.

6. Newman LA, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK, et al. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of local recurrence afterskin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 1998;5:620-626.

7. Yilmaz KB, Dogan L, Nalbant H, et al. Comparing scalpel, electrocautery and ultrasonic dissector effects: the impact on wound complications and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in wound fluid from mastectomy patients. J Breast Cancer 2011;14(1):58-63.

8. Cortadellas T, Córdoba O, Espinosa-Bravo M, et al. Electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing system in axillary dissection: a prospective randomized clinical study. Int J Surg 2011;9(8):636-640.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree