Asymmetry and Architectural Distortion

Asymmetry of the parenchyma is a common finding on mammography, and it is observed when the same mammographic views are visualized together as mirror images. The observation of asymmetry may be related to a greater degree of parenchyma in one breast, loss of parenchyma through surgery, superimposition of parenchyma, or a true lesion that may be benign or malignant. In the current Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) lexicon (1), three terms are used to describe nonmass densities: focal asymmetry, global asymmetry, and architectural distortion. A previously used term for a potential abnormality on a screening study was a density on one view. In this chapter, the etiologies and management of these findings will be described.

A Density Seen on One View

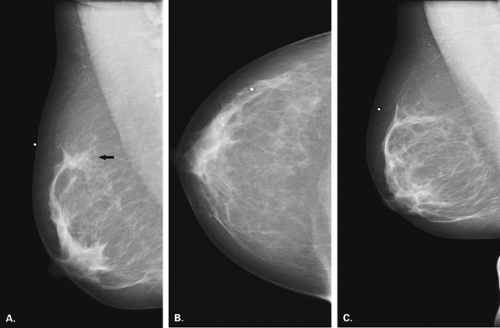

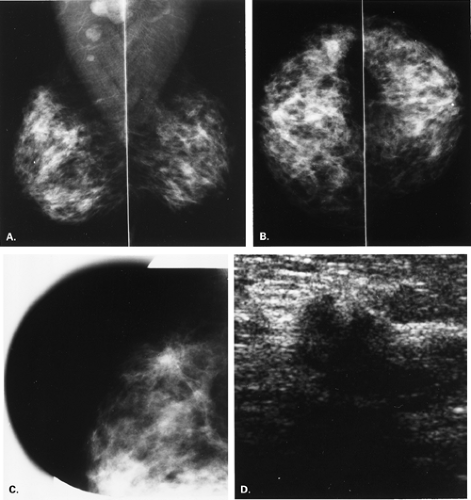

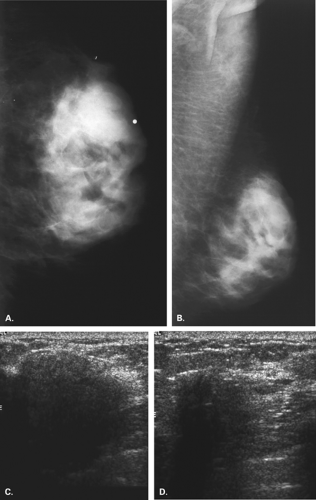

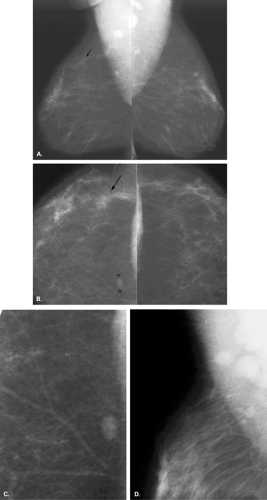

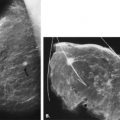

Overlying glandular tissue can be visualized on one projection as a focal density, but on the orthogonal view, it is seen to disperse. Such density may be a pseudolesion that is related to superimposition of the parenchyma, creating the appearance of an asymmetry or mass on one view. A density seen on one view also may be caused by a true lesion that is obscured by dense parenchyma on the other view (Fig. 8.1). In many cases, a single additional image provides sufficient information to differentiate overlapping tissue from a true lesion (2,3,4,5). Spot compression views of the area may be of help in its evaluation and in displacing the surrounding glandular tissue. In addition, off-angle views such as rolled craniocaudal (CC), 90-degree lateral, or step-obliques are used to confirm that a density is a real finding and to verify its location.

The step-oblique mammography technique is used to determine with confidence whether a mammographic finding visible on one projection only represents a summation artifact or if it is a true mass. Pearson et al. (6) described this technique, in which serial images are obtained at 15-degree intervals from the view on which the finding is seen, moving toward the view in which it is not seen. Based on the persistence of the finding or its disappearance on the additional views, the nature of the density can be elucidated (6).

Asymmetry

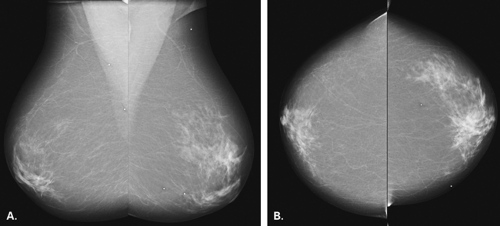

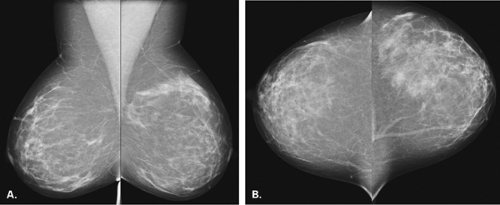

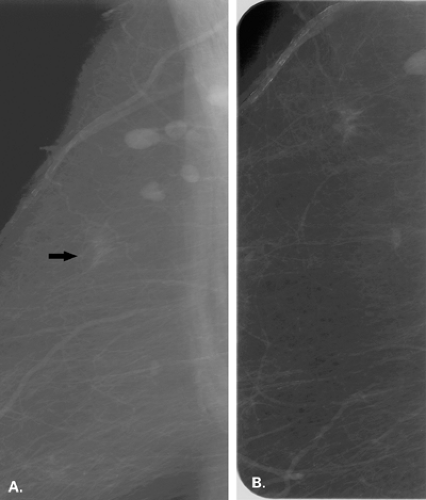

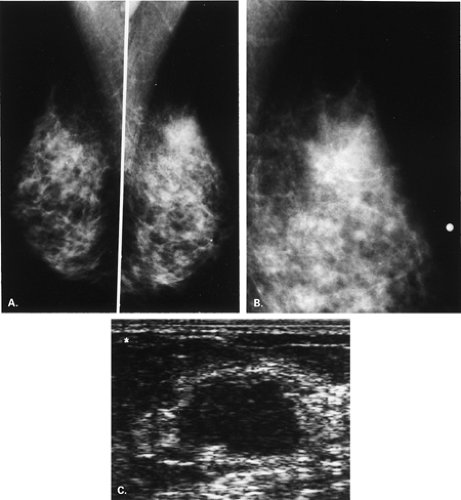

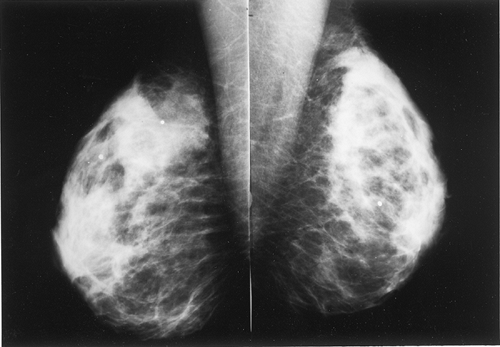

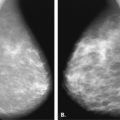

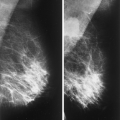

The BI-RADS® lexicon (1) describes a global asymmetry as asymmetric breast tissue or a greater volume of breast tissue in comparison with the corresponding region of the opposite breast. Global asymmetry is usually a normal variant, but when it is palpable or associated with other suspicious findings, it may be significant. For global asymmetry to be considered benign based on mammography, it should not be associated with a mass, architectural distortion, or suspicious microcalcifications. Global asymmetry may be related to a greater volume of parenchyma in one breast, a hypoplastic breast, or the removal of parenchyma in one breast (Figs. 8.2,Figs. 8.3,8.4).

Asymmetric breast tissue has been reported to occur on 3% of mammograms and is most often benign (7). However, asymmetric breast tissue that is new, enlarging, or more dense than on prior mammograms may prompt further evaluation. Piccoli et al. (8) found that a common histopathologic finding in cases of developing asymmetric breast tissue that was biopsied was pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH). In 13 biopsied cases of an enlarging asymmetry, the authors (8) found that PASH was extensive in 12 cases, and in 9%, it was the predominant feature.

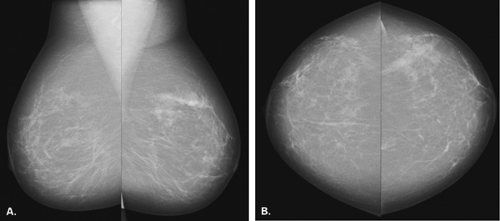

A focal asymmetry, also sometimes called an asymmetric density, refers to an area of tissue that is visible on two views. A focal asymmetry has a similar shape on two views, but it does not have the conspicuity or the borders of a mass (1). A focal asymmetry can represent an island of normal breast tissue, or it can be caused by a variety of benign and malignant conditions. A focal asymmetry that is new or enlarging, palpable,

associated with suspicious microcalcifications or architectural distortion, or that is evident on ultrasound as a solid mass necessitates further evaluation with biopsy. The types of focal asymmetries that may require biopsy are shown in Table 8.1.

associated with suspicious microcalcifications or architectural distortion, or that is evident on ultrasound as a solid mass necessitates further evaluation with biopsy. The types of focal asymmetries that may require biopsy are shown in Table 8.1.

|

The mammographic evaluation of a focal asymmetry is to determine if it has a similar appearance on two views, where it is located, and if it has associated findings (Figs. 8.5 and 8.6). If the asymmetry is most evident on the CC view, rolled lateral and medial CC views are most helpful in addition to the spot compression to determine whether a focal asymmetry is real or not. In addition, the rolled view helps to establish the location of an asymmetry (9). Spot compression magnification helps to identify suspicious microcalcifications associated with the asymmetry as well as the margins of the abnormality.

In addition to the diagnostic mammographic evaluation of a focal asymmetry, ultrasound is also important. Sonography may reveal a solid or cystic mass that accounts for the asymmetric density. The presence of a solid mass that is associated with a focal asymmetry

should be viewed with suspicion. A negative ultrasound may also be helpful to confirm that a focal asymmetry thought to be breast tissue on mammography is benign.

should be viewed with suspicion. A negative ultrasound may also be helpful to confirm that a focal asymmetry thought to be breast tissue on mammography is benign.

The etiologies of focal asymmetries range from normal glandular tissue to benign and malignant entities (Table 8.2). Normal fibroglandular tissue may be the cause of a focal asymmetry on mammography. Normal fibroglandular tissue should not be palpable or associated with distortion or microcalcifications (Table 8.3). Such asymmetries are sensitive to hormonal stimulation and may occur in women on oral contraceptives or on hormone replacement therapy (10). Because of this, a follow-up mammogram in 3 to 4 weeks after discontinuation of hormones may be performed for a questionable asymmetry. Normal fibroglandular tissue usually regresses and may be followed with mammography rather than evaluated further. A persistent new focal asymmetry that developed when the patient was placed on hormones, but that does not diminish with discontinuation of hormonal therapy, should be biopsied.

|

Benign Causes of Asymmetry

Benign etiologies of focal asymmetries are the same as the causes of indistinct masses. Fibrocystic changes (Figs. 8.7 and 8.8), particularly focal fibrosis, and sclerosing adenosis often appear as a focal asymmetry. Sclerosing adenosis is a proliferation of ductules and lobular glands (adenosis) with intralobular and perilobular sclerosis that constricts and distorts the lobular structures. Often lobular-type punctate and round microcalcifications are associated

with this condition. Sometimes, because of the constric- tion of the ductules of the lobule, the microcalcifications contained within these spaces are very small and amorphous.

with this condition. Sometimes, because of the constric- tion of the ductules of the lobule, the microcalcifications contained within these spaces are very small and amorphous.

|

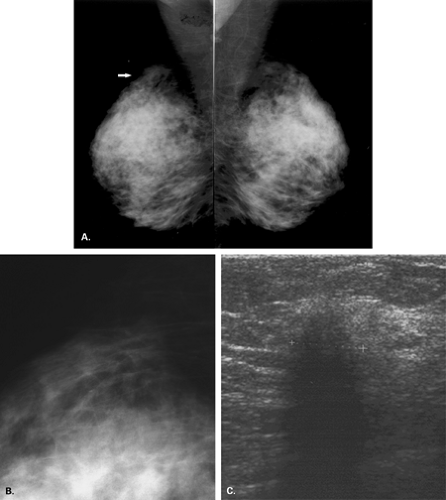

Another benign etiology of focal asymmetry is diabetic fibrous mastopathy (Fig. 8.9). This condition occurs in patients with insulin-resistant type 1 diabetes, who usually present with a palpable breast mass several decades after their diagnosis of diabetes. These patients have impaired breakdown of collagen (11,12), which is thought to be related to the mammographic finding. On mammography, the breast tissue is very dense, and a focal asymmetry may correspond to the palpable mass. Sonography shows dense shadowing that has an appearance suspicious for carcinoma. Needle biopsy confirms the benign nature of the lesion.

In patients who have sustained trauma, a hematoma may be visualized on mammography. Although more commonly presenting as a round mass or indistinct mass, some hematomas may dissipate and have the appearance of a focal or global asymmetry. Clinical correlation is key in suggesting the diagnosis.

Malignant Causes of Asymmetry

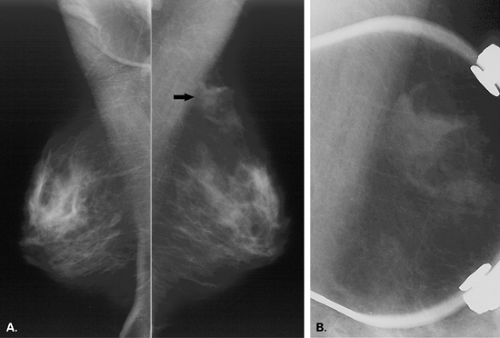

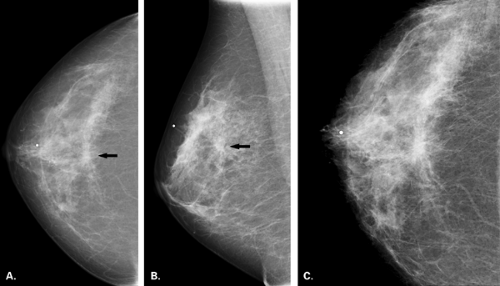

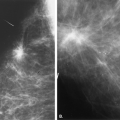

Malignant causes of a focal asymmetry include carcinoma and lymphoma, with lymphoma less likely. Although breast cancer most often presents as a discrete mass with spiculated, indistinct, or microlobulated margins, or as microcalcifications, carcinoma occasionally is evident on mammography as a focal asymmetry (Figs. 8.10,Figs. 8.11,Figs. 8.12,Figs. 8.13,8.14). In a study of 300 patients with mammographically detected clinically occult breast cancers, Sickles (13) found that about two thirds presented with nonclassical findings of breast cancer. Included in these nontypical presentations were a focal asymmetric density and a developing density (13). Because invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) has a diffusely invading pattern of involvement in the tissue, the mammographic manifestations are often subtle and may include an area of focal asymmetry or distortion (14). In addition, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) or even ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) may be diagnosed based on a focal asymmetry on mammography. Of particular concern for malignancy are those asymmetries that are new or associated with a palpable or a sonographic mass, or those with associated suspicious microcalcifications.

Architectural Distortion

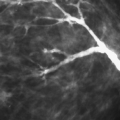

Architectural distortion is spiculation without a central dense mass (1). This finding is visualized in dense parenchyma as a tethering, indentation, or straightening of the breast tissue. In very dense breasts, architectural distortion may appear almost lucent as fat is trapped within the spiculations. In architectural distortion, the spiculation is usually fine and surrounds the center of the lesion. The disruption of the architecture and the spiculation are the findings that allow observation of the distortion in dense breasts.

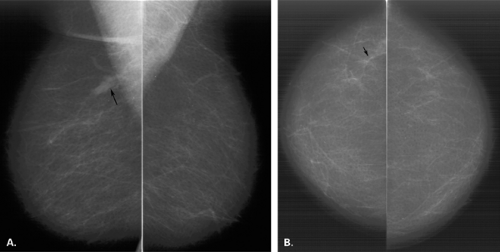

The imaging evaluation of an area of architectural distortion often includes the use of spot compression with magnification (Fig. 8.15). If the distortion is not as clearly evident on one of the routine views as the other, additional off-angle views are important to elucidate the lesion and to help identify its exact location. These views may include rolled CC views if the distortion is best seen on the CC and the mediolateral (ML) view or step-obliques if the lesion is best seen on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view.

In addition to mammographic evaluation, ultrasound (Fig. 8.16) and clinical examination are important in the assessment of an area of architectural distortion. The finding of an associated palpable mass or palpable thickening is suspicious for malignancy. The observation of a scar on the skin under the area of distortion suggests that it might be a surgical scar. In cases of ILC, a palpable mass may not be present even when the tumor is large. However, subtle dimpling of the skin, retraction of the nipple, or deviation of the nipple-areolar complex may occur when the ILC involves the Cooper’s ligaments. On ultrasound, the presence of a solid mass or shadowing is suspicious for malignancy. When this is observed, ultrasound guidance is often used for needle biopsy of the lesion.

Postsurgical Scar

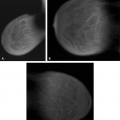

A common benign cause of architectural distortion is a postsurgical scar (Figs. 8.17 and 8.18). Initially after lumpectomy, mammography often demonstrates a hematoma or seroma at the surgical site. Subsequently, as the fluid collection resolves, scarring occurs. The scar may be nearly imperceptible on mammography, or it may be evident as a spiculated mass or as an area of architectural distortion (15). Postsurgical scars usually have a different appearance on the standard mammographic views. On one view, the scar may appear dense and spiculated, but on the other view, it has a more longitudinal shape, and the center appears more radiolucent. The placement of a wire or radiopaque markers on the skin over the surgical scar is helpful to correlate the position of an area of architectural distortion with the prior surgical site.

Comparison with prior images is also helpful to verify that a distortion represents a scar. Importantly, a scar should remain stable or decrease in size on subsequent mammography. An increase in the size of an area of distortion should be regarded as suspicious for malignancy.

In postlumpectomy patients, serial mammography usually allows for the diagnosis of a normal postsurgical scar because of the lack of increase in size of the distortion. However, in questionable cases, magnetic resonance imaging is most helpful to differentiate scar from recurrent tumor.

Other Benign Causes of Architectural Distortion

Sclerosing adenosis is a benign lesion that is a form of fibrocystic change, and it has a pathologic appearance somewhat similar to that of a radial scar. Sclerosing adenosis is a proliferative lesion containing increased ductules and sclerosis that distorts the glands. Microcalcifications are commonly present. The mammographic appearance of sclerosing adenosis may be architectural distortion or a focal asymmetry.

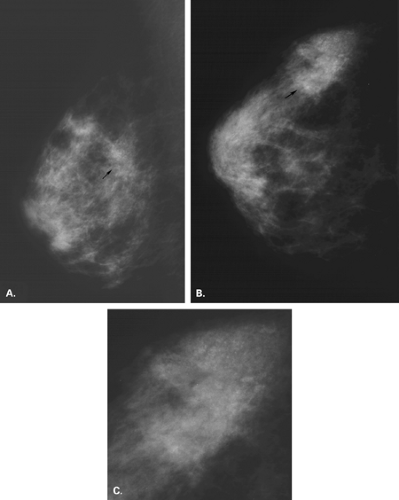

Other forms of fibrocystic change may be identified on biopsy of an area of architectural distortion. Hyperplasias of the common and atypical types, as well as focal fibrosis, may be identified on biopsy of a distortion. Most often, these lesions are smaller, more subtle areas of distortion and not the larger, highly spiculated lesions seen in malignant etiologies (Figs. 8.19,Figs. 8.20,8.21).

Plasma cell mastitis, which is part of the spectrum of duct ectasia, may occasionally present as an area of architectural distortion or focal asymmetry. This is usually located in the immediate subareolar area, where the ducts are ectatic. Like fibrocystic change, plasma cell mastitis is not highly spiculated (Fig. 8.22). In this condition, the inspissated secretions in the ectatic ducts may leak and cause a periductal inflammatory response with fibrosis. Nipple retraction occurs secondary to this response in about 20% of patients.

Radial Scar

Radial scar is a rosettelike proliferative breast lesion (16) that has also been described as sclerosing papillary

proliferation (17), benign sclerosing ductal proliferation (18), nonencapsulated sclerosing lesion (19), infiltrating epitheliosis, and indurative mastopathy (20). The lesion has been confused with cancer by mammographers (21) and pathologists. Most radial scars are microscopic, but some are larger and at gross examination may appear as fine gray to white irregular lesions with central chalky streaks (22).

proliferation (17), benign sclerosing ductal proliferation (18), nonencapsulated sclerosing lesion (19), infiltrating epitheliosis, and indurative mastopathy (20). The lesion has been confused with cancer by mammographers (21) and pathologists. Most radial scars are microscopic, but some are larger and at gross examination may appear as fine gray to white irregular lesions with central chalky streaks (22).

Radial scar or complex sclerosing lesion of the breast is a pathologic entity characterized by a fibroelastic core surrounded by a spoke-wheel pattern of proliferative ducts. The ducts that are trapped in the radial scar often appear sclerosed, and varying degrees of sclerosing adenosis and cyst formation may be seen in the periphery of the lesion (23). Radial scars are also called radial sclerosing lesions, because they contain a sclerosing papillary ductal proliferation (11). Occasionally carcinoma (especially DCIS) or atypical ductal hyperplasia may occur within the ducts of the radial scar. Because of this, most radiologists recommend excision of a radial scar identified on core needle biopsy of the breast.

In a study of 32 cases of radial scars, Andersen and Gram (16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree