9111

Anxiety and Depression in Older Cancer Patients

Rebecca Saracino, Christian J. Nelson, and Andrew J. Roth

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with cancer often develop symptoms of anxiety and depression, which are associated with decreased quality of life, significant deterioration in physical activities, relationship difficulties, and greater pain (1,2). Additionally, comorbid depression and anxiety are of great concern given their negative impact on treatment compliance and adherence (3,4). It is understandable that patients may experience symptoms of general distress, worry, and anxiety given the severity of a cancer diagnosis. However, distress is often experienced on a continuum from minor situational anxiety and transient depressive symptoms to more severe disorders that may interfere with daily functioning and require intervention and treatment.

Several barriers impede the identification of psychopathology in older patients with cancer. For example, the acceptance of significant mood symptoms in people with cancer as “normal” and “expected” by both patients and clinicians is common and therefore may go without mention, discussion, or treatment (5–7). Similarly, there is often pressure on those involved in the patient’s care to “think positively.” Depression may also be normalized in older adults, as somatic symptoms and depressive cognitions are viewed as a routine part of the aging process (8). However, depression, anxiety, and other forms of psychopathology are not an inevitable part of aging or a cancer experience. In fact, most adults report overall increases in well-being as they age (9,10). Therefore, careful consideration and evaluation of these symptoms are warranted in older adults with cancer.

DEPRESSION

The rates of depression in older cancer patients range from 15% to 37% (11–14). Unfortunately, depression can be difficult to recognize in older adults, as they are less likely to report depressed mood, and more likely to present with an anhedonic depression. Anhedonic depression occurs when people lose the capacity to experience pleasure, which must be distinguished from physical limitations of pleasurable behavior (15). The presence of cancer also complicates the ability of clinicians to accurately identify depressive symptoms (16,17). The difficulty in diagnosing depression lies in 92the overlap between the common symptoms of depression and symptoms of cancer and/or side effects of cancer treatment, such as changes in appetite, sleep, energy, and concentration (18–20). Thus, the same symptoms may arise from depression, from the cancer itself, from treatment side effects, or from some combination of the three, thereby leading to incorrect diagnostic assumptions (21–24).

Diagnostic Criteria

A diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) in physically healthy people requires the presence of at least one of the two “gateway” symptoms (i.e., depressed mood, anhedonia) for a minimum period of 2 weeks, most of the day, most days, together with either distress or impaired functioning (25). Additional symptoms of MDD are biophysical (i.e., weight loss or appetite changes, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation, or retardation) and cognitive (i.e., worthlessness or guilt, diminished concentration or indecisiveness, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation). These symptoms are graded by severity (i.e., mild, moderate, severe). The diagnosis of depressive disorder due to another medical condition is given when an individual reports prominent depressed mood and/or anhedonia, and there is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition (25). In cancer, this might be the most appropriate diagnosis when the depressive disorder is clearly associated with the underlying disease or its treatment, even if all diagnostic criteria are not met for MDD.

Diagnostic Considerations for Older Adults With Cancer

Additional key symptoms in older patients that may be helpful to clinicians working in oncology settings (18,26) include “general malaise,” as opposed to being depressed or having loss of interest due to pain or fatigue, or “general” aches and pains or stomach aches, as opposed to specific tumor-site pain or specific side effects of cancer treatment. Many patients with cancer express some hope for a meaningful future regardless of prognosis; thus, reports of little or no hope may be a sign of depression. Sleep may be problematic for all patients with cancer. If the patient wakes up in the middle of the night (middle insomnia), it is important to ask if this is due to a physical issue (e.g., pain, urination, or gastric distress). If the patient has difficulty getting back to sleep, and this is due to worry, ruminative thoughts, or feeling anxious, then this may be an indication of a depressive symptom. An older depressed patient may also report mood variation during the day as opposed to the typical picture of depression—mood may be worse in the morning and may improve as the day continues or vice versa.

ANXIETY

Recent studies found that 25% to 44% of older patients with cancer reported anxiety at levels high enough to warrant referral and treatment (11,12–14). As with sadness or depression, anxiety and stress may be a normal and adaptive initial reaction to a cancer diagnosis. Anxiety can motivate an individual to mobilize his or her practical 93and emotional coping resources in order to respond effectively to a cancer diagnosis. The course of anxiety typically vacillates in parallel with the illness course and events over time, such as awaiting a scan; waiting for the results of a scan or tumor marker test; finding out about a failed treatment or recurrence; or beginning a more aggressive treatment (4,27). However, prolonged and distressing symptoms of anxiety that interfere with an individual’s ability to function optimally warrant intervention.

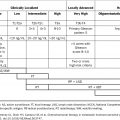

TABLE 11.1 Acute Anxiety Symptoms in the Cancer Setting

■ Uneasiness, unpleasant feeling of arousal, restlessness ■ Irritability ■ Inability to relax; tendency to startle ■ Difficulty falling asleep (leads to fatigue and low tolerance to frustration) ■ Recurring, intrusive thoughts and images of cancer ■ Occasionally, sense of impending doom ■ Distractibility ■ Helplessness and a sense of loss of control over one’s own feelings ■ Symptoms of autonomic arousal: rapid or forceful heartbeat, sweating, unpleasant tightness in stomach, shortness of breath, dizziness ■ Vegetative disturbances: loss of appetite, decreased sexual interest ■ Parasympathetically mediated symptoms: abdominal distress, nausea, diarrhea |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree