Testicular GCT comprise approximately 98% of all testicular neoplasms and are the most common malignancy in males between the ages of 15 and 35 years (

15) (

Table 31.1). They are relatively uncommon; approximately 5,500 to 6,000 new cases will be diagnosed in the United States during this calendar year. Because of their relative rarity, they present a diagnostic challenge to most practicing pathologist. It is remarkable that tumors of such diverse morphology and clinical behavior should be considered as variants of one entity. Nevertheless, there is circumstantial and laboratory evidence to support this practice. First of all, these tumors tend to arise along the axial skeleton, be it the pineal gland, anterior mediastinum, retroperitoneum, or gonads. Second, mixed histologic patterns predominate over tumors with one histologic type. A third compelling piece of evidence relates to the so-called precursor lesion. When these tumors arise in the gonad, irrespective of the morphology, one is likely to identify intratubular germ cell neoplasia (IGCNU), also known in some circles as

in situ carcinoma, in the adjacent seminiferous tubules. A fourth important piece of evidence linking these tumors comes to us from genetics, since approximately 80% of tumors, regardless of the primary site and histology, will have at least one isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12, which is known

as i(12p). This genetic abnormality is not pathognomonic of germ cell neoplasia, yet it is a very useful diagnostic tool in selected circumstances due to its rare occurrence in other solid tumors (

16,

17,

18).

Testicular GCT can be divided into three groups (infantile/prepubertal, adolescent/young adult, and spermatocytic seminoma [SS]), each with its own constellation of clinical histology, molecular and clinical features (

19,

20). They originate from germ cells at different stages of development. The most common testicular GCT arise in postpubertal men, are characterized genetically by having one or more copies of i(12p), and exhibit other forms of 12p amplification and aneuploidy (

21). The consistent gain of genetic material from chromosome 12 seen in these tumors suggests that it has a crucial role in their development. IGCNU is the precursor to these invasive tumors. Their incidence is approximately 6.0 per 100,000 per year with the majority being discovered between 15 and 40 years of age. Several factors have been associated with their pathogenesis, including cryptorchidism, elevated estrogens in utero, and gonadal dysgenesis. Tumors arising in prepubertal gonads are either teratomas or yolk sac tumors (YSTs), tend to be diploid, and are not associated with i(12p) or with IGCNU. The annual incidence is approximately 0.12 per 100,000. SS arises in older patients. These benign tumors may be either diploid or aneuploid and have losses of chromosome 9 rather than i(12p). Intratubular SS is commonly encountered but IGCNU is not. Their annual incidence is approximately 0.2 per 100,000. The pathogenesis of prepubertal GCT and SS is poorly understood.

Intratubular Germ Cell Neoplasia

This term refers to the lesion initially described by Skakkebaek as “carcinoma in situ” (CIS) as well as to other “differentiated” forms of IGCNU (

22,

23,

24,

25). Strictly speaking, the lesion originally described by Skakkebaek is now called “Intratubular germ cell neoplasia, unclassified” (IGCNU) by most, at least in the Western Hemisphere.

The story of testicular “CIS”/IGCNU is fascinating and serves as a paradigm for the concept of progression from incipient or preinvasive neoplasia to invasive disease (

24,

26,

27). In 1972, Skakkebaek reported “atypical spermatogonia” in two men undergoing testicular biopsies during a workup for infertility who subsequently developed invasive TGCT. He hypothesized that these cells constituted “CIS.” Two subsequent seminal studies by his group proved that this was indeed the case. In 1978, he reported a series of 555 men who underwent testicular biopsies for infertility (

26,

27). They identified six patients with evidence of “CIS.” With a median follow-up period of approximately 3 years, three of these patients developed evidence of an invasive germ cell tumor; one of them with bilateral disease. The remaining 449 patients were tumor free during the same follow-up period.

In 1986, the Skakkebaek group reported their experience with contralateral biopsies in 500 patients with unilateral GCT (

28). Twenty seven patients (5.4%) were found to have “CIS.” Eight patients received systemic chemotherapy for advanced disease. Of the remaining 19 patients, 7 (37%) developed invasive GCT at this site within the follow-up period. Mathematical modeling suggested that 50% of biopsy-positive cases would develop disease within 5 years. Remarkably, not a single case of contralateral GCT developed in the remaining 463 biopsy-negative patients during the same follow-up period. In a subsequent report, the authors revealed that at least two of the biopsy-positive cases that received systemic therapy subsequently developed contralateral tumors, suggesting that systemic therapy is not always effective against preinvasive disease (

29).

It is clear that the original lesion described by Skakkebaek is the precursor to all types of GCT, at least for those that originate in postpubertal gonads, other than SS. In early 1980, a group of distinguished pathologists including Drs. Robert Scully, Juan Rosai, F.K.K. Mostofi, and Robert Kurman met in Minnesota to discuss nomenclature of incipient germ cell neoplasia. They agreed that “CIS” was a poor choice to describe this lesion since it had no features of epithelial differentiation. They suggested the term “IGCNU,” because it was associated with all morphologic types of GCT with the exception of SS. It also underscores the fact that differentiated forms of IGCN may occur, including intratubular embryonal carcinoma.

IGCNU can be seen adjacent to invasive GCT in virtually all cases in which residual testicular parenchyma is present (

22,

30). As previously mentioned, it is present in up to 4% of cryptorchid patients, in up to 5% of contralateral gonads in patients with unilateral GCT, and in up to 1% of patients biopsied for oligospermic infertility. Its association with TCGT arising in prepubertal patients is still a source of controversy (

19,

31,

32) While some authors suggest that it does not occur,

others state that it does. In either case, we can state with reasonable certainty that, if IGCNU does occur in childhood tumors, it is certainly less apparent.

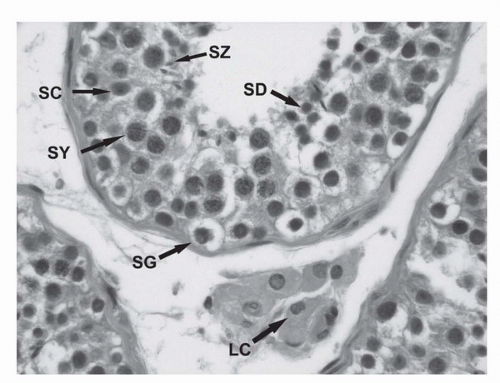

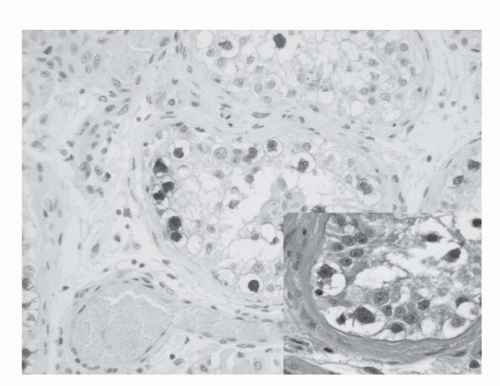

IGCNU is characterized morphologically by the presence of enlarged, atypical germ cells located immediately above a usually irregularly thickened basement membrane (

Fig. 31.3). The atypical cells are either isolated or form a single row along the basement membrane. They are typically larger than spermatogonia, the other cell that usually resides near the basement membrane. IGCNU cells have clear cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, coarse chromatin, and enlarged nucleoli, which may be single or multiple. On the other hand, spermatogonia may also have clear cytoplasm but the cells are small, have round and regular nuclear contours, densely packed chromatin, and absent nucleoli (

Fig. 31.2). In most cases, tumor-bearing tubules do not have active spermatogenesis and contain mostly Sertoli cells. Sertoli cells may be displaced toward the tubular lumen. Characteristically, they contain a single nucleolus that is small and regular. The nuclei are oval or round with regular borders and the chromatin is fine. The cytoplasm is amphophilic/eosinophilic and not vacuolated.

In essence, the cytologic features of classic IGCNU are those of seminoma. The relationship is supported by the coexpression of a host of histochemical and immunohistochemical markers among both cell types. Further evidence comes from electron microscopy, which has shown that both share common ultrastructural features including the absence of well-developed cytoplasmic intermediate filaments, inconspicuous organelles, glycogen particles, lack of mature desmosomes and cell junctions, and nucleoli with ropy nucleolonema. Tubules whose lumen is filled with these cells may be regarded as “intratubular seminoma.”

IGCNU may extend into the rete testis, usually undermining the epithelium in a “pagetoid” pattern. At times, the epithelium may become hyperplastic and in this setting, it is important not to confuse this finding with the presence of nonseminomatous germ cell tumor.

IGCNU cells contain glycogen and thus are PAS positive, diastase sensitive. Rarely will other intratubular cells, either spermatogonia or Sertoli cells, show similar positivity. Placental-like Alkaline Phosphatase (PLAP) is one of the isoforms of alkaline phosphatase (

Table 31.2). PLAP antibodies will stain IGCNU as well as the majority of seminomas and embryonal carcinomas (EC) as well as a smaller percentage of YSTs. Immunoreactivity is seen in virtually all cases of IGCNU and the staining pattern is usually membranous or cytoplasmic. None of the other nonneoplastic intratubular cells are immunoreactive for PLAP, but immunoreactivity may be seen in other types of non-germ cell malignancies (

33,

34,

35,

36). C-kit (CD 117) is expressed in a large percentage of IGCN as well as seminomas, but not in other GCT (

37). Once again, the staining pattern is cytoplasmic/membranous. Despite the overexpression of this antigen, c-kit is rarely mutated in these tumors. Other antibodies which immunoreact with IGCNU but are rarely used in clinical practice include M2A and 43-F (

36,

38,

39). POU5F1 (Oct3/4) is a very interesting marker which was described earlier in this decade (

40). The gene serves as a transcription factor and its product is expressed in pluripotent mouse and human embryonic stem cells and is downregulated during differentiation. Since the gene is also required for self-renewal of embryonic stem cells, knocking out the gene is lethal. Early reports suggest that this antigen is expressed solely in IGCNU, seminoma and embryonal carcinoma, suggesting that these are the types of GCT cells with pluripotency, that is, with capacity to differentiate. In any event, it provides us with yet another marker for IGCNU (

Fig. 31.3).

It is important to keep in mind that the presence of neoplastic cells within tubules does not always constitute IGCNU and that one must adhere strictly to the established diagnostic criteria. Besides intratubular seminoma, one can encounter intratubular embryonal carcinoma, intratubular SS, and even metastatic disease such as melanoma and prostatic carcinoma. Intratubular lymphoma and even mesothelioma may also be confused with IGCNU.