INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of the anal canal is a rare malignancy representing approximately 2.5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. It is estimated in 2015 that over 7,200 patients will be diagnosed with carcinoma of the anal canal in the United States, resulting in greater than 1,000 deaths (1). The incidence of this disease continues to rise steadily. A practicing oncologist will evaluate and treat less than one such patient per year. The majority of anal carcinoma arises within the mucosa of the anus and is of squamous cell histology (2). Traditionally, 74% to 90% of carcinomas of the anal canal are cured with the combined modalities of chemoradiation, reserving an abdominoperineal resection (APR) for salvage therapy of persistent or recurrent disease (3). This chapter focuses on treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal and the potential innovative strategies that lie ahead.

ANATOMY/HISTOLOGY

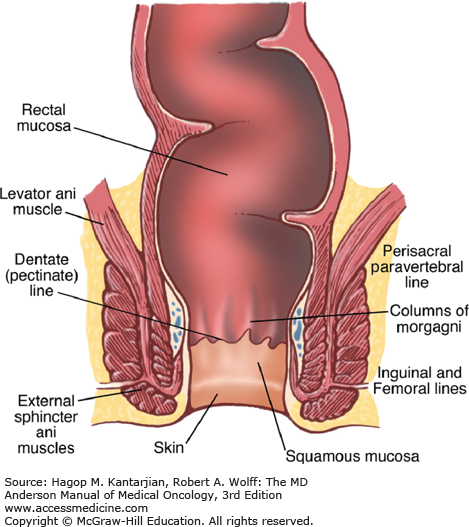

The anal canal is approximately 4 cm wide and is composed of the region extending from the proximal anorectal ring to the distal anal verge (margin) (Fig. 25-1). Because various definitions of the normal anal canal anatomy exist, classifying these tumors by a histologic definition based on the lining mucosa offers a more consistent approach to guide diagnosis and treatment (2).

Malignancies of the anal margin are treated as primary skin cancers and are often surgically excised. The rectal mucosa adjacent to the anorectal ring is composed of columnar epithelium. A transition zone of both cuboidal and columnar epithelium (6-12 mm in length) extends from the distal rectum to the dentate line. The dentate line separates the columnar epithelium (columns of Morgagni) of the proximal anal canal and the squamous epithelium of the distal canal, which extends to the anal verge. The anal verge is the convergence of squamous epithelium and the anal margin. The anal margin comprises the dermis, located within 5 cm of the anal verge.

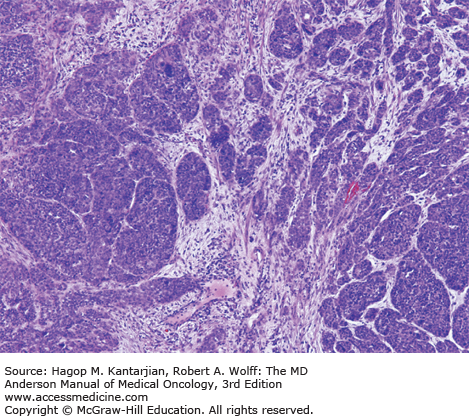

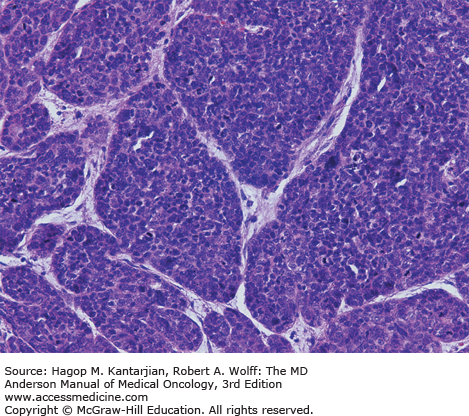

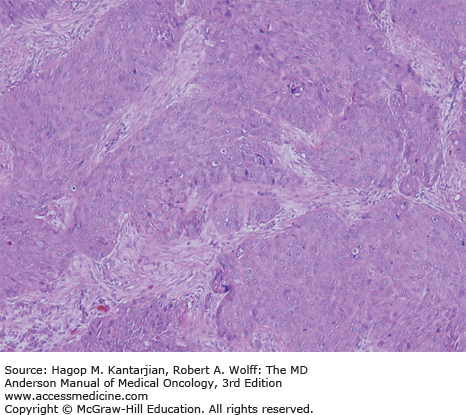

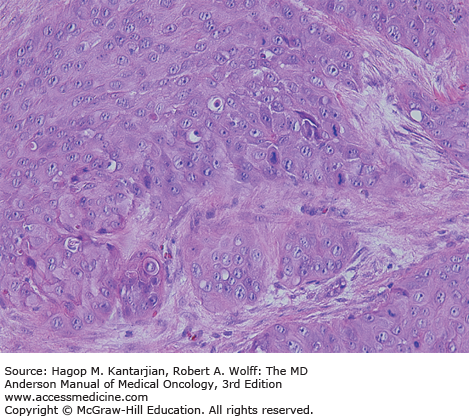

The mucosa of the transition zone, formally referred to as the cloacogenic mucosa, represents 66% of the lesions now commonly referred to as nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (Figs. 25-2 and 25-3) (4). Tumors distal to the dentate line are usually keratinizing SCC (Figs. 25-4 and 25-5).

The vascular supply of the anal canal consists of the superior, middle, and inferior rectal vessels that originate from the inferior mesenteric, internal iliac, and internal pudendal arteries, respectively. Lymphatic drainage superior to the dentate line is identical to rectal carcinomas flowing to the perirectal and paravertebral nodes. Tumors located inferior to the dentate line drain to the inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. A complete physical examination should include examination of the lymph nodes of the groin.

ETIOLOGY

Multiple risk factors have been associated with the development of carcinoma of the anal canal. Benign conditions such as hemorrhoids, fissures, and anal fistulas have not been determined to be causal factors (5). Rather, it has been postulated that these benign conditions may instead represent the initial symptoms of anal cancer (5).

The pathogenesis of developing anal cancer is largely related to infection with specific subtypes of human papillomavirus (HPV), most commonly with HPV-16 or HPV-18. Common risk factors associated with anal cancer include a history of more than 10 sexual partners; receptive anal intercourse before the age of 30; and sexually transmitted diseases, including condyloma acuminata (genital warts, attributed to HPV), gonorrhea, herpes virus, hepatitis, Chlamydia trachomatis, or a history of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (6,7,8). Women with a history of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer are three to five times more likely to develop anal cancer as opposed to stomach or colon cancer, demonstrating the link between sexual activity and likely field cancerization effects from prior high-risk HPV infection (9).

Human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted disease in the United States and has been strongly associated with the development of anal carcinoma (10). It is estimated that 75% of men and women of reproductive age have been infected with genital HPV.

High-risk subtypes HPV-16 and HPV-18 are associated with anal cancer—and also cervical dysplasia—and may result in anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). Human papillomavirus subtype 16 reportedly results in a greater incidence of high-grade AIN (11). However, unlike cervical dysplasia, AIN is a premalignant condition for which standard screening methods currently have not been universally recommended and have been limited to select high-risk individuals.

A systematic literature review on HPV type distribution in anal cancer showed a combined prevalence of HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 of 72% in invasive anal cancer, with the prevalence of HPV-16 being the highest in these cases, as in cervical cancer (12). A cohort of patients with metastatic SCC of the anal canal at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) revealed the presence of HPV, via detectable HPV DNA and/or expression of the protein p16, in 68 (95%) of 72 tumor samples analyzed (13). Therefore, HPV appears to be found in the vast majority of anal cancers.

The presence of HPV also has been reported to be a positive prognostic biomarker for patients with nonmetastatic SCC of the anal canal. In one study of patients with stages I to III anal cancer, HPV was detected in 120 (88%) of 137 tumors analyzed. In a multivariate analysis, p16 expression was determined to be associated with an improvement both in overall survival and disease-specific survival relative to patients with HPV-negative tumors (14).

Introduction in 2006 and 2009 of the prophylactic vaccines Gardasil and Cervarix, respectively, directed against primary infection by HPV has demonstrated efficacy in reducing precancerous anogenital lesions caused by the targeted subtypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 (15,16,17). In late 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the introduction of a nonavalent vaccine targeting nine HPV subtypes (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58). A large, double-blind placebo-controlled study of men who have sex with men between 16 and 26 years of age demonstrated that the use of a quadrivalent vaccine against HPV not only was safe and well tolerated but also decreased the incidence of precancerous AIN (18). These findings generate early optimism that this preventative approach may decrease the incidence of this disease in the future. Even though initially approved for the vaccination of adolescent females, Gardasil has subsequently received extended FDA approval for males of the same age category after it was shown to be efficacious and may offer a promising primary prevention strategy in both genders (19).

Although a direct relationship between HIV and carcinoma of the anal canal has not been clearly established, a strong correlation exists between HIV and HPV. Compared with HIV-negative patients, HIV-positive patients are two to six times more likely to be diagnosed with HPV regardless of sexual practices and are also more likely to have a persistent infection (20,21). Human immunodeficiency virus–positive men and women exposed to HIV are less likely to clear the virus and become HPV negative (21,22). For patients who are infected with HIV, the prevalence of anal carcinoma is greater and cancer presents at a younger age of onset than in HIV-negative patients (23).

Solid organ transplantation has been associated with a 10-fold increased risk of developing anal cancer and a 20-fold increased risk for vulvar and vaginal cancers (24). A recent population-based cohort study conducted using the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry (DCR) from 1978 to 2005 found that HIV infection, solid organ transplantation, hematologic malignancies, and a range of specific autoimmune diseases were strongly associated with increased risk of anal SCC (25).

Prior case-control studies have indicated that chronic tobacco use may result in a two- to five-fold increased likelihood of developing anal cancer (26). Moreover, tobacco smoking appears to be associated with recurrence of anal carcinoma and is related to increased mortality; thus, smoking cessation should be encouraged once a diagnosis of anal carcinoma is made (27).

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

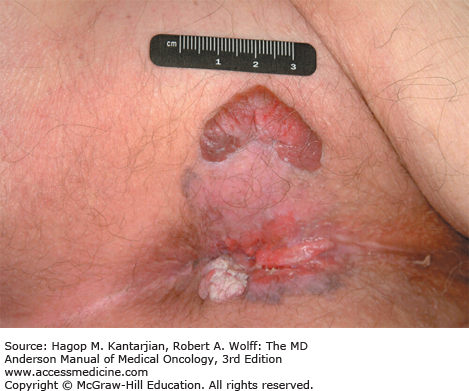

The mean age of diagnosis is approximately 62 years (28). The most common presenting complaint is rectal bleeding. Other symptoms may include tenesmus, pain, local irritation, discharge, or a change in bowel habits. Clinically enlarged lymph nodes are present in 15% to 25% of patients at presentation (29). Extreme case presentations may include a fungating perianal mass or a verrucous mass, as seen in Figs. 25-6 and 25-7.

A diagnostic evaluation should consist of a complete physical examination including examination of the inguinal lymph nodes, a digital rectal examination (DRE), and evaluation of the surrounding mucosa of the anus. Diagnostic studies should include proctosigmoidoscopy or anoscopy, chest x-ray, and computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis to rule out distant disease. A transrectal or transvaginal ultrasound may be of added benefit in accurate disease staging (30,31,32,33). Histologic confirmation is recommended, with a tissue biopsy of the suspected area and/or fine-needle aspiration of any palpable inguinal lymph nodes because this may impact the radiation fields. An HIV test should be considered in all patients, and a one-time test for hepatitis C infection may also be considered for patients born before the year 1965 given the disproportionately high risk of incidence of viral infection for patients in this age range (34).

STAGING AND PROGNOSIS

The staging classification system for anal cancer was adopted by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The T stage, unlike most gastrointestinal malignancies, is not dependent on the degree of tumor tissue penetration but rather on the size of the primary tumor site.

Carcinomas of the anal margin are commonly excised with complete resolution of the tumor. Independent poor prognostic features include tumor size (T stage) with a clear distinction in prognosis between T2 and T3 tumors (23,35,36). Patients with T1 to T2 tumors have an expected 5-year survival of 80%, whereas patient with T3 to T4 tumors have an expected median 5-year survival of <20% (28). Inguinal lymph node involvement may reduce the cure rate by 50%, with increased nodal stage also being a significant prognostic factor (37,38,39,40). Multivariate analysis of the results from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 98-11 trial indicates that tumor-related prognosticators for poorer overall survival included node-positive status (hazard ratio [HR], 1.88), large tumor diameter >5 cm (HR, 1.30), and male sex (HR, 1.38; P = .031) (41).

CHEMORADIATION—NIGRO REGIMEN

A pivotal approach led to the anecdotal finding that surgery may not be necessary for curative intent in the treatment of SCC of the anal canal (42). The benefits of combined chemoradiation in other gastrointestinal malignancies prompted Nigro and colleagues to consider the use of chemotherapy as a radiation sensitizer. Patients received concomitant 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C, which was administered along with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (30 Gy). The pathologic specimens in three of three patients failed to demonstrate any viable tumor. This observation culminated in the use of chemoradiation as the primary treatment modality for the treatment of anal cancer and revolutionized the approach to its treatment. The Nigro approach of chemoradiation has subsequently been evaluated in several other small phase II studies with radiation doses ranging from 30 to 60 Gy.

A retrospective analysis from the Princess Margaret Hospital reviewed the outcomes of patients who had been treated with (1) radiation alone, (2) 5-FU/mitomycin C, (3) split-course 5-FU/mitomycin C, or (4) split-course 5-FU (43). The 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) was significantly improved in the 5-FU/mitomycin C arms versus 5-FU alone (76% vs 64%). Although the combination of 5-FU/mitomycin C was superior in locoregional control (LRC) with the addition of mitomycin C (86% vs 60%), the use of split-course radiation resulted in decreased morbidity, notably acute skin toxicities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree