Thomas A. Russo

Agents of Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is an indolent, slowly progressive infection caused by anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria, primarily from the genus Actinomyces, which normally colonize the mouth, colon, and vagina. Disruption of mucosa may lead to infection of virtually any site. When the organisms invade tissue, they form tiny, sometimes visible clumps, called grains or “sulfur granules,” named for their yellow color. Lesions of actinomycosis are purulent foci surrounded by dense fibrosis. Clinical presentations are myriad. Once common in the preantibiotic era, today the incidence of actinomycosis is diminished and, as a result, so is its timely recognition.1,2 At the time actinomycosis was much more common, it was called “the most misdiagnosed disease” and it was stated that “no disease is so often missed by experienced clinicians.”3 Needless to say, actinomycosis still remains a diagnostic challenge today despite technologic advances.4 Three clinical presentations that should prompt consideration of this unique infection are (1) the combination of chronicity, progression across tissue boundaries, and masslike features, which mimics malignancy (with which it is often confused); (2) the development of a sinus tract, which may spontaneously resolve and recur; and (3) a refractory or relapsing infection after a short course of therapy, because cure of established actinomycosis requires prolonged treatment. An awareness of the full spectrum of disease manifestations prompting clinical suspicion will expedite diagnosis and treatment and minimize unnecessary surgical interventions and morbidity and mortality that all too often occur with actinomycosis.

Etiologic Agents

Actinomycosis is most commonly caused by the gram-positive higher bacterium Actinomyces israelii.5 Additional species that are established but less common causes of actinomycosis include A. naeslundii,6 A. viscosus,7 A. odontolyticus,8 A. meyeri,9 and A. gerencseriae (formerly A. israelii serotype II). Propionibacterium propionicum (formerly Arachnia propionica) has been described as a cause of actinomycosis,5 but most recent reports primarily describe this pathogen as causing lacrimal canaliculitis,10 although a case of pelvic disease was recently described.11

Until recently, classification of Actinomyces spp. was based on differences in phenotypic testing (see “Diagnosis” later). However, advances in microbiologic taxonomy, using genotypic methods such as comparative 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA)10,12 or sequencing of alternative genes,13 have led to the identification of many new Actinomyces species from both human and animal specimens. These methods have also led to the reclassification of certain “classic” Actinomyces species as Arcanobacterium, Actinobaculum, or Cellulomonas.10,14,15 Presently, 46 species and 2 subspecies have been recognized (www.bacterio.cict.fr/a/actinomyces.html). Although the syndrome of actinomycosis can be caused by these more recently described agents,16,17 most of the infections are not “classic” actinomycosis. Actinomyces europaeus,10,14,18–20 Actinomyces neuii,19,21–24 Actinomyces radingae,10,14,19,25,26 Actinomyces graevenitzii,27 Actinomyces turicensis,10,14,17,19,25 Actinomyces georgiae,28 Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes,29 Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) bernardiae,30,31 Actinomyces funkei,19,32,33 Actinomyces lingnae,19 Actinomyces houstonensis,19 Actinomyces massiliiensis,34 Actinomyces timonensis,35 and Actinomyces cardiffensis16,36 are capable of causing a variety of human infections. Infections due to A. neuii have been increasingly recognized, with endovascular infection and abscesses most commonly described. Interestingly, thoracic or abdominal infection due to A. neuii has not yet been described.37

When an adequate bacteriologic evaluation is performed, most if not all actinomycotic infections are polymicrobial in nature.1,5 Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans, Eikenella corrodens, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, Capnocytophaga, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterobacteriaceae have been commonly isolated in various combinations, depending on the site of the infection. The contribution of these additional isolates to the pathogenesis of actinomycosis is difficult to assess; however, it seems reasonable to consider them as being potential copathogens when designing therapeutic regimens.

Epidemiology

The agents of actinomycosis have been clearly established as members of the endogenous flora of mucous membranes. The frequency of oral cavity colonization with Actinomyces is nearly 100% by 2 years of age.38 It is also often cultured from the gastrointestinal tract, bronchi, and female genital tract. It has never been cultured from nature, and there are no documented cases of person-to-person transmission.39 Although the normal habitats for the more recently identified Actinomyces spp. have not been optimally defined, data available to date suggest that these species are also members of the endogenous oral, gastrointestinal, and genital flora.19 Possible transmission via a lamb bite has been described in a single report.40

Actinomycosis has no geographic boundaries. Infection may occur in individuals of all ages. The peak incidence of actinomycosis is reported to be in the mid-decades, with cases in individuals younger than 10 and older than 60 years being less frequent.5,41 Nearly all series have reported males to be infected more frequently than females, at a ratio of approximately 3 : 1.1,5,41,42 Plausible but unproven explanations for this discordance include poorer dental hygiene and increased oral trauma in males.41

Studies on the occurrence of actinomycosis estimated a yearly incidence of 1 : 100,000 in the Netherlands and Germany in the 1960s and 1 : 300,000 in the Cleveland area during the 1970s, making this disease uncommon but not rare.41 Its frequency is undoubtedly diminished since the preantibiotic era, when this disease was not only common but more malignant in nature. Improved dental hygiene and early antimicrobial treatment of infections before the development of a characteristic actinomycotic syndrome are likely contributing factors. However, individuals or populations that do not have access to dental or medical care, or both; prolonged use of an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) (see “Pelvic Disease” later); and bisphosphonate use (see “Oral-Cervicofacial Disease” later) are likely at higher risk. Furthermore, many unrecognized cases probably occur, especially oral-cervicofacial disease, and are successfully treated empirically.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

A pivotal step in the pathogenesis of actinomycosis is disruption of the mucosal barrier. Oral and cervicofacial disease is frequently associated with dental procedures, trauma, oral surgery, head and neck radiotherapy, or oncologic surgical procedures.43 Pulmonary infections often arise in the setting of aspiration, and abdominal infection is usually preceded by conditions that result in loss of mucosal integrity, such as gastrointestinal surgery, diverticulitis, appendicitis, or foreign bodies (e.g., fish bones).1,41 Recognition of factors that enable bacterial entry into deep tissues, however, may be absent.42 The lack of such a history should not prevent consideration of this disease when the clinical circumstance is appropriate.

Other bacterial species concomitantly present have been designated “companion organisms.” They may serve as copathogens by aiding in the inhibition of host defenses or by reducing oxygen tension. The difficulty in establishing an animal model of infection with Actinomyces alone and enhancement of infection by coinoculation of E. corrodens support the concept that additional organisms are important for the initiation of infection.44 Further, coaggregation of Actinomyces and Streptococcus spp. occurs and results in increased resistance to phagocytosis and killing.45

An acute inflammatory phase manifested by a painful cellulitic reaction is occasionally observed with oral-cervicofacial disease or with soft tissue infection elsewhere in the body. The chronic phase of this disease is more often seen.42 Classic disease is characterized as a densely fibrotic lesion that undergoes slow, contiguous spread and ignores tissue planes. However, no studies have addressed the bacterial factor(s) responsible for the unique pathogenesis of this disease. Lesions usually appear as either single or multiple indurated swellings. As the lesion matures, it becomes soft and fluctuant and suppurates centrally. The fibrous walls of the mass have been characteristically described as “wooden” and, in the absence of suppuration, have been frequently confused with neoplasms. This extensive fibrosis, which is one of the hallmarks of this disease, may be minimal, especially in pulmonary and central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Given time, sinus tracts will often extend from the abscess to either the skin or adjacent organs or bone, depending on the location of the lesion. Sinus tracts can spontaneously close and then reform. Overlying skin may assume a red to bluish hue. Hematogenous dissemination can occur from these local sites and occasionally be fulminant, although in the antibiotic era this clinical syndrome has become rare.

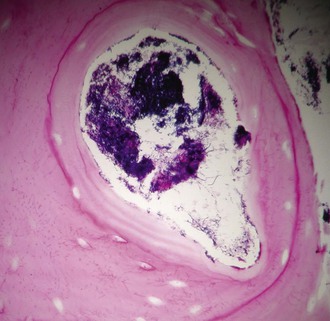

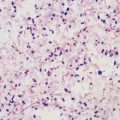

Microscopically, lesions have an outer zone of granulation, consisting of collagen fibers and fibroblasts. There is a central purulent loculation that contains neutrophils that surround the sulfur granules present. Granules are conglomerations of organisms and are virtually diagnostic of this disease. Bacterial biofilms may contribute to granule formation.46 One to six may be present per loculation, and they range from microscopic to macroscopic in size (see “Diagnosis” later). As many as 50 loculations may be present per lesion, and these loculations are separated by granulation tissue or foamy macrophages and may undergo coalescence. Lymphocytes and plasma cells are usually present, and eosinophils are seen in 15% of abscesses. Multinucleated giant cells are occasionally seen, primarily in pulmonary lesions, but they have also been described in disease elsewhere.42 Suppuration is a constant feature of active disease but may not be present in all areas of the lesion.

The association of pelvic actinomycosis with IUCDs suggests that at least this foreign body contributes to pathogenesis, perhaps enabled by biofilm formation.47 Associations with actinomycosis and foreign material elsewhere are less strong. Several reports describe periapical actinomycosis associated with root canal fillings, mandibular osteomyelitis associated with wire used in the treatment of a fracture, infection of the tongue in the presence of a foreign body, and a transobturator sling.48 Actinomyces infecting prosthetic joints, through presumed hematogenous spread, is rare but reported.49 Aspirated or ingested foreign bodies may contribute to pathogenesis via facilitating the growth and survival.

Cases of actinomycosis have been described in the setting of steroid use,50 infliximab treatment,51,52 bisphosphonate treatment,53 acute leukemia during chemotherapy,54 organ transplantation,55 common variable immunodeficiency,40 chronic granulomatous disease,56 and human immunodeficiency virus infection.57 Ulcerative mucosal lesions (herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, chemotherapy) and abnormalities in host defenses likely facilitated the development of actinomycosis in some human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated cases; however, it remains unclear which arm(s) of the host defense are critical in preventing or controlling this infection and the degree to which the incidence of infection is increased in these settings.

Clinical Manifestations

Oral-Cervicofacial Disease

Actinomycosis most commonly occurs and is best recognized in this location, with a mean of 55% of cases.41

Oral-cervicofacial disease can present as a soft tissue swelling, an abscess, a mass lesion,41,58 or, occasionally, an ulcerative lesion.59 The diagnosis of actinomycosis should not only be considered in the classic setting of a painless mass at the angle of the jaw (Fig. 256-1) but should be included in the differential diagnosis of any lesion in the head and neck region. When lesions appear solid, neoplasm is the usual diagnostic consideration. Soft tissue infections of the head and neck may also present as chronic, recurring abscesses. This common scenario of temporary improvement with a short course of empirical antibiotic therapy, followed by relapse, should always arouse suspicion for actinomycosis, regardless of the location. As the disease spreads to adjacent structures, there is little regard for normal tissue planes. Lymphatic spread and associated lymphadenopathy are uncommon. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance images usually reveal an infiltrative, well- or ill-defined mass with inflammatory changes.60 Extension to any contiguous structure may occur, including the carotid artery, orbital cavity, cranium, cervical spine, trachea, or thorax.61,62,63,64 Pain, fever, and leukocytosis are variably present.41

Periapical and endodontic infection caused by Actinomyces probably occurs far more frequently than is recognized.65 Appropriate dental intervention and antibiotic therapy usually result in cure before more extensive disease develops.

The most common location for diagnosed actinomycosis is the perimandibular region. Periapical infection or trauma is often, but not always, the inciting event. The classic lesion located at the angle of the jaw is the most frequent location (submandibular), but the cheek, submental space, retromandibular space, and temporomandibular joint may be affected.66,67 As noted, a hallmark of this disease is the potential for contiguous extension. Spread to the skin may result in sinus tract(s) formation, and these can spontaneously close and open elsewhere. The overlying skin often develops a bluish or purplish red hue. Involvement of the muscles of mastication frequently occurs, resulting in trismus.1 Associated mandibular periostitis or osteomyelitis may also be present but is surprisingly infrequent.68 A lytic lesion, rarefaction with sclerosis, or sclerosis alone may be seen, and this latter pattern may be confused with tumor.69 Maxillary disease, including osteomyelitis, occurs less frequently.70 Associated soft tissue lesions and maxillary sinus or cutaneous fistulas, or both, can occur. Maxillary and ethmoid sinusitis may present as isolated disease or can be concomitant with infection of the maxilla.71,72 The hard palate may also be involved, with presentation as a mass lesion.1

Two clinical settings have been recently recognized for contributing to an increased incidence of actinomycotic infection of the mandible and maxilla.53 The first is infected osteoradionecrosis, a complication of radiation therapy used in the treatment of head and neck cancer. The second has been termed bisphosphate-associated osteonecrosis (Fig. 256-2). Bisphosphonates are increasingly used to reduce bone disease, particularly due to multiple myeloma and for the prevention of osteoporosis. Although our understanding of the pathogenesis of these syndromes is evolving, it appears that the first insult is radiation therapy or bisphosphonates, or both, altering the local host defenses followed by disruption of the mucosa, usually from dental procedures, thereby enabling Actinomyces to access and infect the gingiva and bone.73

Isolated masses or ulcerative lesions can also occur in the tongue,74 vallecula,75 nasal cavity,76 nasopharynx,77 soft tissues of the head and neck,41,78 salivary glands,79 patent thyroglossal duct,80 thyroid,81 branchial cleft cyst, and hypopharynx, larynx, or both.82 Although grains are frequently seen in tonsilar clefts on histopathology of excised tonsils, they appear not to be the cause of recurrent tonsillitis or obstructive tonsillar hypertrophy. The absence of a pathologic tissue reaction around the grain makes a causal role for both of these entities unlikely.83–86

Actinomycosis is also an uncommon but important cause of otitis media; untreated cases may result in fatal extension into the mastoid and then the CNS. It is characterized by numerous episodes of otitis media that transiently respond to conventional short-course therapy and resistance to myringotomy. Diagnosis can be made by the pathologic and microbiologic examination of infected material from the affected middle ear that may appear to be a cholesteatoma.87 Infection of the external ear and temporal bone may occur from the spread of facial disease.

Actinomyces and P. propionicum can cause lacrimal canaliculitis.88 Actinomyces has also caused postoperative endophthalmitis after intraocular lens implant89 and keratitis after laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis.90 Rarely, secondary extension into the orbit from infected maxillary or ethmoid sinuses can occur.

Thoracic Disease

Thoracic involvement comprises approximately 15% of cases of actinomycosis.91 Aspiration of organisms from the oropharynx is the usual source of infection, which may be facilitated by foreign material/bodies. Direct extension can occur from disease in either the head and neck or abdominal cavity; however, such secondary spread has become increasingly uncommon since the advent of efficacious antimicrobial therapy.

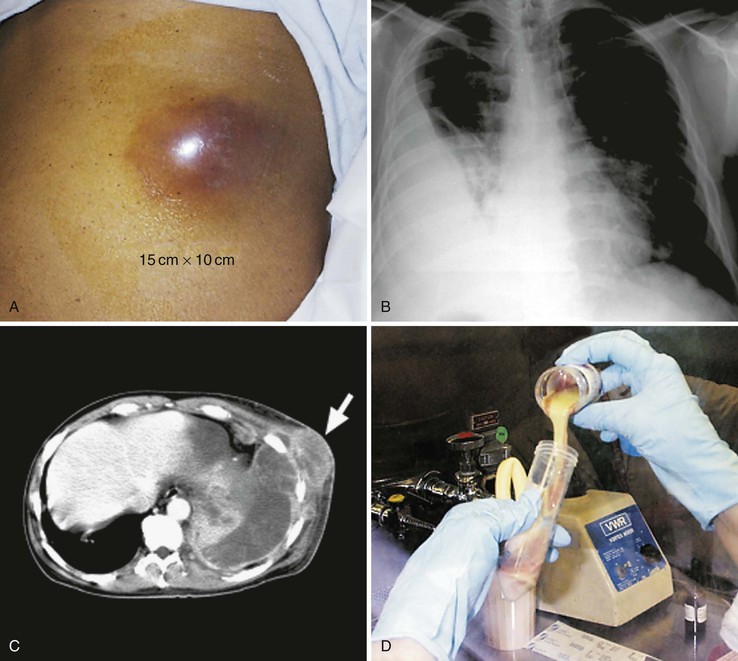

The most common clinical presentation is an indolent, slowly progressive process that involves some combination of the pulmonary parenchyma and pleural space. Chest pain, fever, weight loss, and, less commonly, hemoptysis are prominent symptoms, and a cough, when present, is variably productive.91 A relapsing pneumonia after a short treatment course should make actinomycosis a consideration. There are no specific radiographic manifestations, and any lobe may be involved. The usual appearance is either a mass lesion or pneumonia with or without pleural involvement (Fig. 256-3).92 Pleural thickening, effusion, or empyema is present in greater than 50% of cases of thoracic actinomycosis (see Fig. 256-3B). Rarely, actinomycosis may present as an isolated effusion. The spontaneous drainage of an empyema through the chest wall should raise suspicion for this disease.93 Cavitary disease may develop and is more readily detected by computed tomography (CT) scans because multiple small cavities are more common than large ones.94 Hilar or mediastinal adenopathy may be present. Pulmonary disease that extends across fissures or pleura (see Fig. 256-3C), involves the mediastinum, or has contiguous bony disease should suggest actinomycosis and is also more readily appreciated by CT.92 Likewise, extension to the chest wall with the development of a soft tissue mass, a draining sinus, or both, are telltale signs when present (see Fig. 256-3A). In the absence of these classic scenarios, however, thoracic actinomycosis is almost never suspected. It is mistaken for either malignant disease, with the diagnosis made by the pathologist postresection, or for an empyema or pneumonia secondary to more usual causes. Tuberculosis, nocardiosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, mixed anaerobic infection, bronchogenic carcinoma, lymphoma, mesothelioma, and pulmonary infarction are among the entities confused with pulmonary actinomycosis.

Other less common manifestations of thoracic actinomycosis include multiple pulmonary nodules, miliary disease, infection of surgical bronchial stumps, and endobronchial lesions, which may be associated with aspirated foreign bodies.95,96 Primary breast disease either presents as a persistent or recurring abscess(es) or mimics malignancy,20 and infection of a mammary prosthesis has also been described.97

Endocarditis, Pericarditis, and Mediastinal Disease

Mediastinal actinomycosis is an uncommon event. The structures within the superior, anterior, middle (heart), or posterior mediastinum can be involved alone or in combination, resulting in a diverse array of clinical presentations. Infection usually results from contiguous spread from the thorax but can arise from perforation of the esophagus, chest trauma, or extension of head and neck or abdominal disease.98 Involvement of cardiac structures represents the majority of mediastinal infections reported. Pericarditis is most common and may be initially asymptomatic or hemodynamically insignificant, but if allowed to progress, cardiac tamponade and constrictive or adhesive pericarditis will develop.4 Less frequently, myocardial or endocardial infection occurs, either via extension from the pericardium99 or by initial hematogenous seeding of the endocardium.100 Involvement of the left common carotid, left subclavian, and aortic arch can occur with superior mediastinal disease.101 Anterior mediastinal involvement may present as an isolated mass or, rarely, superior vena cava syndrome.102 Concomitant anterior chest wall infection is common, but associated sternal disease is rare. Posterior mediastinal involvement may result in paraspinous muscle and soft tissue disease, esophageal fistula or encasement, or vertebral body infection, or both. Because of the slow progression of the disease, both vertebral body destruction and new bone formation occur, resulting in a mottled, saw-toothed, or honeycombed appearance of bone on radiograph. The transverse processes, and with disease progression the pedicles and spinous processes, are similarly involved as the bodies, in contrast to their usual sparing with tuberculosis. The corresponding posterior ends of ribs are usually involved, and a typical wavy periostitis may be present, but, unlike tuberculosis, vertebral body collapse and disk space narrowing are not usually seen. Extension to the epidural space with spinal cord compression may occur.103 Primary esophageal disease with and without HIV infection has also been described.57

Abdominal Disease

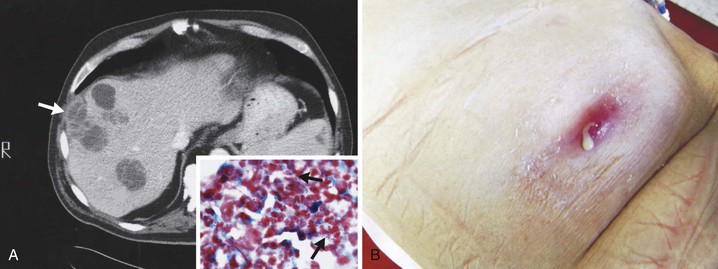

The proportion of reported cases involving the abdomen averages 20%.41 Any disease or event that allows the agents of actinomycosis to breach the gastrointestinal mucosa has the potential to be complicated by this infection. The majority of abdominal infections are due to this mechanism, although the inciting conditions are not always apparent. However, it is important to note that ascension from the female genital tract of IUCD-associated actinomycosis has become an increasingly recognized source of abdominal disease.104 Hematogenous dissemination, extension from the thorax, and spillage of bile or gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy105 are other portals of entry. As a consequence of the flow of peritoneal fluid, direct extension of primary disease, or both, virtually any abdominal organ, region, or space can be involved either alone or in combination regardless of the initial site of infection. Abdominal actinomycosis is perhaps the greatest diagnostic challenge. This infection is rarely considered before the clinical laboratory or pathologist establishing the diagnosis. Months to years usually pass from the time of the inciting event to clinical recognition of this indolent disease.42 Associated symptoms are generally nonspecific, with fever, weight loss, change in bowel habits, abdominal pain, or a sensation of a mass being most common. Abdominal actinomycosis usually presents either as an abscess or as a firm to hard mass lesion that is often fixed to the underlying tissue and mistaken for tumor.106 Sinus tracts or extension to either the abdominal wall or perianal region may develop (Fig. 256-4). CT findings usually demonstrate a mass lesion with focal areas of decreased attenuation or a thick-walled cystic mass, both of which frequently enhance with contrast. Lesions often appear invasive, suggesting a tumor, but associated lymphadenopathy is uncommon.107,108 With colonic involvement, mucosal nodules with associated inflammation may be observed.109

Appendicitis, especially with perforation, is the most common predisposing event and is associated with 65% of the cases of actinomycosis originating in the abdomen. As a result, the right iliac fossa is the most frequent primary site of abdominal disease and right-sided abdominal infection is more common than left. It is also one of the potential inciting events for tubo-ovarian infection. Diverticulitis or foreign body perforation of the transverse or sigmoid colon tends to be associated with left-sided disease and accounts for 7.3% of cases, a surprisingly low percentage considering the incidence of diverticulitis. The loss of gastric mucosal integrity from peptic ulcer disease or gastrectomy may result in abdominal infection and is associated with 4.4% of cases. Isolated gastric disease, including a case after gastric bypass, has also been described.110 Additional associations with abdominal infection include antecedent bowel surgery, typhoid fever, amebic dysentery, chicken or fish bones, trauma, and hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Interestingly, actinomycosis rarely develops as a consequence of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Perirectal or perianal disease may result from extension of pelvic infection or, less commonly, abdominal disease. Primary disease occurs with either local mucosal damage or infection of anal crypts. The most common presentation is single or multiple perianal abscesses, sinus or fistula tract formation, or both. Infiltrating masses may develop in the buttock, posterior thigh, scrotum, or inguinal region.111 Recurrent disease over months to years or wounds that fail to heal after drainage or fistulotomy are clues that should suggest actinomycosis, particularly in the absence of documented inflammatory bowel disease. Strictures of the rectum can also occur and cause an alteration of bowel habits, mimicking primary bowel or metastatic prostatic or pelvic tumors.112 This presentation is most often due to extension of pelvic disease.

Hepatic infection was present in 5% of all cases of actinomycosis.42 Spread to the liver occurs via extension from a contiguous abdominal focus or hematogenously from more distant but established abdominal or extra-abdominal foci. A case associated with a pancreatic stent has also been described.113 Hepatic involvement is common in disseminated actinomycosis. The entity of primary or isolated disease is presumably hematogenous seeding from cryptic foci. Single or multiple abscesses or lesions suggesting neoplasia are the usual presentation (Fig. 256-5).114 Generally, a more indolent course is observed compared with the more usual causes of pyogenic hepatic abscesses, but “companion organisms” may contribute to a more acute presentation.115 Symptoms and laboratory findings often point to the right upper quadrant, but liver functions tests may be normal. The presently available imaging modalities and percutaneous diagnostic techniques have allowed for an increasing number of cases to be diagnosed without surgery. Uncommon presentations or sequelae of hepatic actinomycosis include cholangitis, portal vein occlusion/thrombosis, cholestasis, and extension into the thorax.116,117 Splenic infection is less common.118