Adverse Events in Cancer Genetic Testing: Medical, Ethical, Legal, and Financial Implications

Karina L. Brierley

Erica Blouch

Whitney Cogswell

Jeanne P. Homer

Debbie Pencarinha

Christine L. Stanislaw

Ellen T. Matloff

Over the past decade, cancer genetic counseling and testing have become essential services in progressive cancer care. With this evolution, there has been much debate over who is best suited to provide genetic services. Traditionally, genetic counseling and testing have been provided by individuals with graduate education, specialized training, and board certification in genetics. However, the push in recent years by some professional organizations and genetic testing companies has been to suggest that all health care providers should provide genetic counseling and testing services themselves. The impetus for this push on the part of the genetic testing companies is controversial, in that the aggressive sales representatives from these companies receive financial incentives for every test ordered and every new ordering provider.

Some potential benefits for provision of genetic counseling and testing by all health care providers, and not just specialists, have been proposed.1,2 These benefits include that established providers have long-term relationships with their patients and thus deeper knowledge of the patient’s overall health and that this may allow greater access to genetic services particularly in underserved populations where there are geographical, cultural, or language barriers.1,2 Conversely, much of the literature over the past decade cites potential barriers, areas of concern, and negative outcomes from genetic counseling and testing being performed by providers without specialized training in this area.2,3 Besides a handful of well-known lawsuits, little has been published demonstrating actual clinical examples of adverse outcomes resulting from cancer genetic counseling and testing performed by clinicians without specialization in this area.

In 2010, we published the first known national series of cases of this kind.3 In this chapter, we will discuss additional cases and controversies. Both the cases in this chapter and those published in our previous series were obtained from genetic counselors who participate in the National Society of Genetic Counselors Cancer Special Interest Group listserv. For the current chapter, genetic counselors from the National Society of Genetic Counselors Cancer Special Interest Group were invited in January 2012 to

submit cases of adverse outcomes of cancer genetic counseling and testing performed by providers without specialization in this area for inclusion in a case series publication. Cases were chosen for inclusion that illustrated unique themes/major patterns of errors in cancer genetic counseling and testing. Cases included originated from five of the United States (California, Connecticut, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Tennessee). Multiple colleagues informally reported additional cases but were unwilling to formally report them for inclusion, citing fear of pushback from the clinicians involved and/or potential conflicts with the commercial company that performs much of the cancer genetic testing in the United States and is also the largest employer of genetic counselors in the United States.

submit cases of adverse outcomes of cancer genetic counseling and testing performed by providers without specialization in this area for inclusion in a case series publication. Cases were chosen for inclusion that illustrated unique themes/major patterns of errors in cancer genetic counseling and testing. Cases included originated from five of the United States (California, Connecticut, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Tennessee). Multiple colleagues informally reported additional cases but were unwilling to formally report them for inclusion, citing fear of pushback from the clinicians involved and/or potential conflicts with the commercial company that performs much of the cancer genetic testing in the United States and is also the largest employer of genetic counselors in the United States.

We will also review the literature on the factors that may contribute to these errors and the potential barriers and areas of concern related to clinicians without extensive knowledge, training, or certification in genetics providing cancer genetic counseling and testing.

Themes in Clinical Case Reports

Wrong Testing Ordered

In many of the reported cases, the wrong genetic test was ordered. In some cases, this led to inaccurate medical management recommendations, and in others, unnecessary testing and expenditure of health care dollars.

Wrong Testing Ordered, Resulting in Inaccurate Medical Management Recommendations

In one case, a 19-year-old unaffected female patient of Italian ancestry presented to a gastroenterologist for reflux and gastrointestinal symptoms. The doctor elicited a family history of polyposis in the patient’s father and documented that he had “screened the patient for an APC gene mutation” (associated with familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP]). The patient’s blood work from that visit indicated a normal complete blood count and F5L screen (i.e., a normal assay for activated protein C, also abbreviated “APC”). A colonoscopy was neither ordered, nor was the patient referred to genetics. Notes from the patient’s follow-up care with this physician make no further mention of genetics or FAP. A year later, the patient was seen by a new physician and referred for a colonoscopy and cancer genetic counseling. Testing ordered by the genetic counselor revealed that the patient carried a detectable APC gene mutation, and the patient was found to have polyposis upon colonoscopy. The original gastroenterologist in this case ordered the wrong test and apparently closed the case based on a false-negative result. Ninety-three percent of patients with classic FAP go on to develop colorectal cancer by the age of 50 years without colectomy.4 The average age at diagnosis of colon cancer in untreated individuals with FAP is 39 years.4

In another case, a 63-year-old unaffected woman of English, not Jewish, ancestry was seen by her primary care physician because of her concerns about her family history, which included a sister diagnosed with ovarian cancer and a mother who

died of early-onset breast cancer. The primary care physician ordered testing for the three BRCA mutations that are common among individuals of Jewish ancestry, which was negative. The patient received a copy of the test results with a note from her physician, “BRCA (smiley face).” The sister with ovarian cancer later had full sequencing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and was found to carry a BRCA2 mutation (not the one common among Ashkenazi Jews, as expected on the basis of their ancestry). Five years later, the original patient was referred to a cancer genetic counselor by her radiologist to make sure she had had the correct testing. The genetic counselor ordered testing for the familial BRCA2 mutation identified in the sister, and the patient, fortunately, tested true negative. However, if she had carried the mutation, many serious adverse consequences (including cancer diagnoses) could have resulted for her and her at-risk adult children from her not knowing her correct BRCA status for many years.

died of early-onset breast cancer. The primary care physician ordered testing for the three BRCA mutations that are common among individuals of Jewish ancestry, which was negative. The patient received a copy of the test results with a note from her physician, “BRCA (smiley face).” The sister with ovarian cancer later had full sequencing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and was found to carry a BRCA2 mutation (not the one common among Ashkenazi Jews, as expected on the basis of their ancestry). Five years later, the original patient was referred to a cancer genetic counselor by her radiologist to make sure she had had the correct testing. The genetic counselor ordered testing for the familial BRCA2 mutation identified in the sister, and the patient, fortunately, tested true negative. However, if she had carried the mutation, many serious adverse consequences (including cancer diagnoses) could have resulted for her and her at-risk adult children from her not knowing her correct BRCA status for many years.

In a third case, an oncologist referred a 23-year-old woman of Mexican, not Jewish, ancestry who was recently diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer for genetic counseling. The referral read “genetic counseling and BRCA testing for surgical decision making.” Upon taking the patient’s family history, the counselor learned that the patient had a sibling who was diagnosed with a glioblastoma at age 14 years and died at age 16 years. Based on the patient’s personal history of very early-onset bilateral breast cancer and family history of a childhood brain tumor, the genetic counselor instead ordered testing for mutations in the p53 gene associated with Li–Fraumeni syndrome. The patient was found to carry a p53 mutation, and therefore, learned she was not a good candidate for chest wall irradiation. The patient had previously been counseled by her physician that she would need a prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 23 years because of the association of BRCA mutations and ovarian cancer, and this suggestion (which would have been controversial, even in a BRCA carrier) was difficult to counter with the patient even after a p53 mutation had been identified.

Unnecessary Testing/Misuse of Health Care Dollars

Ordering the wrong genetic testing can also lead to the unnecessary expenditure of thousands of dollars, which is then charged to the insurance company and/or the patient. In one such example, a patient was seen by his surgeon based on the fact that his sister carried a known MSH2 mutation associated with Lynch syndrome. The surgeon ordered full sequencing of the MSH2 gene through his office’s laboratory, and the charge for this testing with the laboratory send-out fees was $4,700. The patient’s insurance, justly, denied payment for this test. The patient was then seen by a cancer genetic counselor when his daughter decided to pursue testing. He was very upset when he learned that the appropriate testing (for the single familial mutation) would have cost $475. The patient was also angry that, despite all of this extra expense, his doctor had given him little pertinent Lynch syndrome information except that he carried the same mutation that his sister carried; he had not been given detailed information about his cancer risks, screening recommendations, and risks and recommendations for other family members.

Results Misinterpreted

Misinterpretation of genetic test results was another common error observed in our series of cases. Many of the cases of result misinterpretation involved variants of uncertain significance, which are among the more difficult results to interpret. However, other cases demonstrated that result misinterpretation occurred in simple, straightforward cases.

Result Misinterpretation, Resulting in an Advanced Cancer Diagnosis

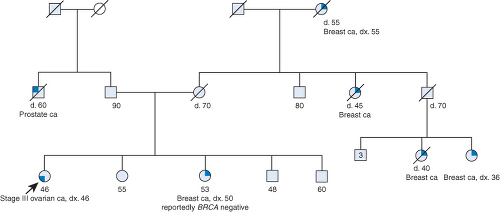

A 46-year-old woman of Polish, not Jewish, ancestry was referred to cancer genetic counseling because of her recent diagnosis of stage III ovarian cancer and strong family history of breast cancer (Fig. 4.1). She initially reported that one of her relatives who had breast cancer had BRCA testing in a different country and tested negative. At the end of her appointment, she recalled that she had BRCA testing through her gynecologist’s office 16 months earlier at age 45 years and was told it was “normal.” However, after discussing that she would now meet the testing company’s criteria for large rearrangement testing (BART) in BRCA1/2 at no additional cost, the patient chose to proceed with testing. Upon receiving the request for this additional testing, the laboratory sent the genetic counselor a fax indicating that the patient would not qualify for free BART rearrangement testing because her initial testing was positive for a deleterious mutation in BRCA1. The counselor contacted the ordering gynecologist to determine what had occurred and what the patient had been told about her results. The gynecologist was shocked, and very upset, to learn that the patient carried a mutation and to realize that she had misinterpreted the result, which was clearly printed in capital letters in a box at the top of the page. The gynecologist had noticed only the wording listed next to the BRCA2 gene and a targeted rearrangement panel that indicated that no mutation was detected in that gene. The gynecologist contacted the patient about this error, and the patient was then seen for follow-up genetic counseling.

The patient and her husband were painfully aware that if her results had been read correctly 16 months earlier, she could have had a prophylactic BSO and probably avoided a likely fatal advanced ovarian cancer diagnosis. The patient and her husband indicated that they planned to sue her gynecologist.

The patient and her husband were painfully aware that if her results had been read correctly 16 months earlier, she could have had a prophylactic BSO and probably avoided a likely fatal advanced ovarian cancer diagnosis. The patient and her husband indicated that they planned to sue her gynecologist.

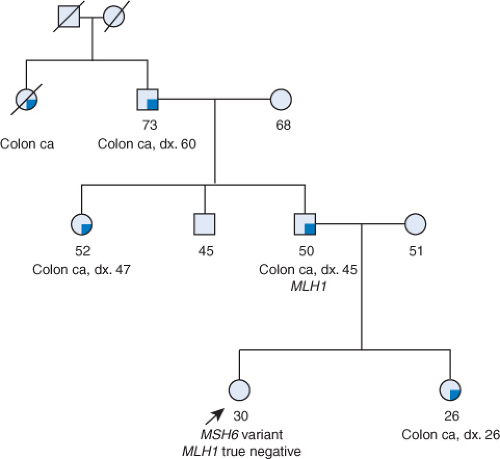

Figure 4.1. Pedigree for a female patient whose BRCA1 positive test result was misinterpreted as negative, resulting in an advanced ovarian cancer diagnosis. |

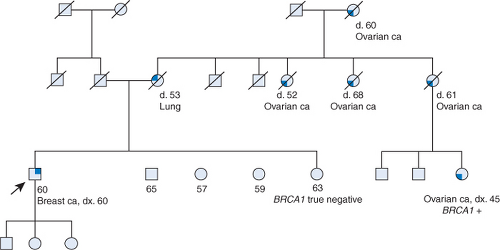

Figure 4.2. Pedigree for a male patient whose sister’s BRCA negative test result was misinterpreted leading to a delay in testing and an advanced male breast cancer diagnosis. |

Another case in which the significance of test results was misinterpreted demonstrates how inaccurate information given to one patient can impact multiple other family members. A 60-year-old man of Irish ancestry diagnosed with breast cancer was seen for cancer genetic counseling based on his personal history and his family history that included five cases of ovarian cancer (Fig. 4.2). One of his maternal cousins with ovarian cancer carried a known BRCA1 mutation. The patient reported that his sister was tested for this familial BRCA1 by her gynecologist and learned that she did not carry this mutation. She was told that since she did not have this mutation, none of her siblings (including this gentleman) would carry this mutation, and none of them needed testing. After his cancer diagnosis, this gentleman had testing and learned that he carried the familial BRCA1 mutation. He was angry that his sister and their family had been given misinformation about their risks. He indicated that he would have sought care for the lump he had found behind his nipple much sooner if he had known he was at increased risk, and this may have allowed him to be diagnosed at an earlier stage, avoid chemotherapy, and to have a better prognosis.

Result Misinterpretation, Leading to Unnecessary Prophylactic Surgery

A 42-year-old patient with a confirmed diagnosis of FAP and an APC gene mutation was referred for genetic counseling by her gastroenterologist because she had had genetic testing several years earlier through her colorectal surgeon, but had never had formal genetic counseling. When the genetic counselor took the

patient’s personal history, she learned that the patient had had a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 41 years based on her surgeon’s assessment that she “was at an increased risk for cancer there” because of her genetic test results. The surgeon had apparently confused the cancer risks associated with FAP with the ovarian and uterine cancer risks seen with Lynch syndrome. This patient had undergone unnecessary surgery and premature menopause because of this misinformation.

patient’s personal history, she learned that the patient had had a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at age 41 years based on her surgeon’s assessment that she “was at an increased risk for cancer there” because of her genetic test results. The surgeon had apparently confused the cancer risks associated with FAP with the ovarian and uterine cancer risks seen with Lynch syndrome. This patient had undergone unnecessary surgery and premature menopause because of this misinformation.

One of the more common result misinterpretations in this, and previous, case series was a variant of uncertain significance being falsely interpreted as a known disease-causing mutation. In one case, a 30-year-old woman was referred to a cancer genetic counselor after being tested by her gastroenterologist and told that she carried an MSH6 mutation (Fig. 4.3). The patient sobbed through her appointment with the genetic counselor indicating that her doctor had told her that she would need to have a hysterectomy, and therefore, would not be able to have children. She had never had a diagnosis of cancer but had a strong family history of colon cancer including her father, sister, paternal aunt, and paternal grandfather diagnosed at ages 45, 26, 47, and 60 years, respectively (Fig. 4.3). Upon reviewing her test results, the genetic counselor discovered that the patient actually carried a variant of uncertain significance. Many of the affected relatives were living, so genetic testing was recommended in an affected relative. Her father had genetic counseling and testing, and learned that he carried a deleterious MLH1 mutation. The patient subsequently had testing and learned that she did not carry the MLH1 mutation identified in her father that was responsible for the cancers in her family. She was thus not at increased risk for colon, uterine, and ovarian cancer, and did not need to have a prophylactic hysterectomy.

Inadequate Genetic Counseling

In some cases, inadequate genetic counseling was the main error that occurred and included incomplete information about implications and options for the patient and/or their family members and practices that go against widely accepted ethical principles in cancer genetic counseling and testing.

Ethical Issues

The parents of a 7-year-old healthy girl of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, at the urging of a relative who is a physician, obtained a test kit from a genetic testing company and requested that their daughter’s pediatrician order BRCA testing based on their Jewish ancestry and the father’s family history of ovarian cancer. The pediatrician complied with their request, and the child was found to carry a BRCA1 mutation. When the parents were seen for genetic counseling, they were upset to learn that this information would also directly impact whichever parent carried the mutation in terms of increased cancer risk and that either of them could carry this mutation and should have testing since they were both of Jewish ancestry. Upon learning the future impact of this mutation for their daughter and the fact that her medical management in childhood would not change based on this information, they left indicating that they wished they had not had her tested at this time. When there is no immediate medical benefit (i.e., interventions that can be offered in childhood), it is almost universally recommended that testing for adult-onset conditions be deferred until adulthood when the individual can make an informed decision about testing because there are potential risks or concerns about testing in childhood including adverse psychosocial reactions, discrimination, and stigmatization.5,6,7,8,9 This recommendation is also based on the ethical principles of respecting the autonomy of the child and their right not to know.5,6,7,8,9

Potential Factors Contributing to Errors in Cancer Genetic Counseling and Testing

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree