(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

Some primary tumors in the pelvis (usually soft tissue sarcomas) extend to the greater pelvis with lateral extension often to one of the iliac fossae, distending the lower abdominal wall forward and reaching all the way to the level of the umbilicus or higher. Similarly, tumors arising in the mid abdomen, as they grow, may descend and adhere to the walls of the pelvis creating difficulty for the surgeon to come around their distal surface for control of the major vessels (external iliac). These tumors often have been called unresectable because the surgeon cannot achieve distal exposure, and therefore is unable to perform a dissection between the distal portion of the tumor and the external iliac or femoral vessels, or an en bloc resection of the tumor with the iliofemoral vessels. The external iliac and femoral vessels are referred to as distinct entities in anatomical texts, because the lower musculoaponeurotic layers of the anterior abdominal wall and the inguinal ligament conceal the former when the groin is opened, and the intact groin conceals the latter when the lower abdomen is opened. The abdominoinguinal incision imposed by the needs of exposure for the dissection of tumors in this area shows the iliac and femoral vessels in their continuity and functional unity, suggesting the term iliofemoral vessels as expressive of this unity when surgically considered in the resection of tumors in their vicinity. A midline abdominal incision cannot expose the iliac or femoral vessels distally, so the surgeon cannot combine the exposure of the lower abdominal aorta, common iliac vessels, with the distal external iliac and femoral vessels on the same side in continuity. In the past patients with tumor presenting with unilateral fixation to the wall of the pelvis, external iliac vessels, and iliac fossa were offered and often were treated with hemipelvectomy. Actually, the tumor in the pelvis may extend to both sides, so it may be necessary to expose the external iliac and femoral vessels on both sides in continuity with the common iliac vessels and the lower abdominal aorta. Because the iliopsoas inserts in the lesser trochanter, sarcomas located in the area of the iliac fossa may extend behind the inguinal ligament into the groin and thus present difficulty in their exposure through an abdominal or flank incision, neither of which provides in continuity exposure of the groin. Tumors also may adhere to or invade the external iliac vessels. If this occurs all the way down to the inguinal ligament, their resection is difficult because the usual incisions cannot expose simultaneously in one field the lower abdominal aorta–inferior vena cava and the common iliac, external iliac, and femoral vessels on one or both sides. Soft tissue or other tumors with fixation to the lateral wall of the lesser pelvis also present difficulty in resection and often are called unresectable because a midline incision cannot give adequate exposure of the obturator foramen and the external iliac vessels down to the level of the inferior epigastric vessels. Furthermore, some tumors that are in the lesser pelvis adhering to the pelvic wall also infiltrate the ipsilateral pubic bone and extend through the obturator foramen to involve the adductor group of muscles. Tumors in these locations have often been called unresectable, or they have been resected via a hemipelvectomy of the ipsilateral extremity.

From the above discussion, it is obvious that an incision is needed that would provide not only the exposure of the lower abdominal cavity provided by a midline incision, but also exposure in continuity of the same groin as the tumor location. This kind of incision may be called an abdominoinguinal incision, as it provides in-continuity exposure of both the lower abdomen and the groin on one or both sides [1–7].

Abdominoinguinal Incision: The Making of the Incision and Its Applications

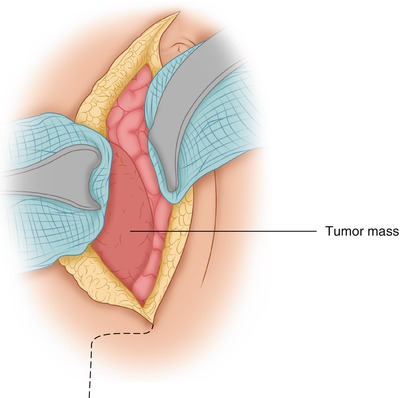

We performed the first abdominoinguinal incision on March 16, 1979 (Fig. 41.1). It was several months later, after the performance of a few similar cases, that we realized that despite the specificities of the individual operations arising from the specificities of the individual tumors and patients, there was a common structure in the sequence and aim of the operative steps, which was the in continuity exposure of the lateral pelvis (and by extension, of the peritoneal cavity) to the involved groin. The need for in continuity exposure was predicated by the need to preserve the vascular supply of the ipsilateral lower extremity while a satisfactory margin was attained around the tumor. By the time of publication of the Atlas of Operations for Soft Tissue Tumors, in 1985 [1], we had performed 22 cases with the abdominoinguinal incision, and by October 2012 about 150 such operations. In the following, the main features of this incision are presented with each operation described along with the more common deviations from the basic technique, in order to counter specific circumstances.

Fig. 41.1

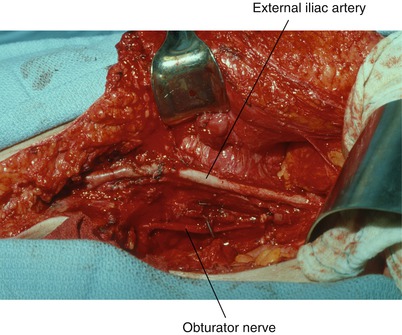

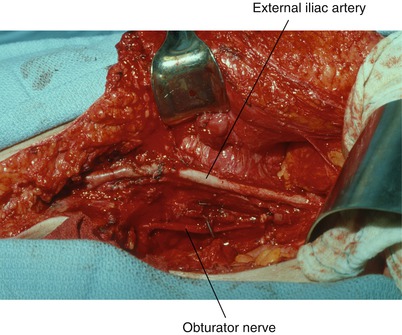

The operative field is shown after resection of sarcoma of the right groin and right lateral pelvis. The right iliofemoral vein, which was occluded, has been removed. A small vein patch repaired the wall of the artery. This was the first abdominoinguinal incision that we used, done on the guidance provided by the needs to resect the tumor. After a few similar cases, we realized that this could be a formal incision

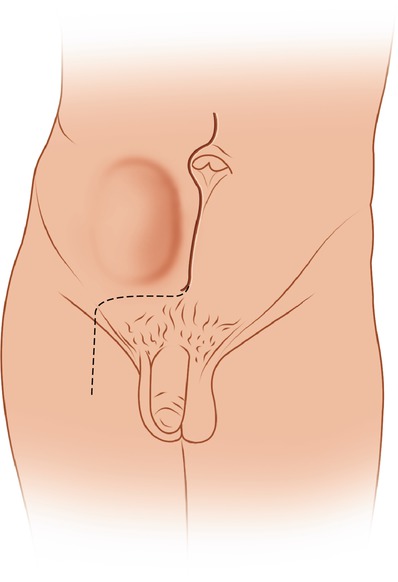

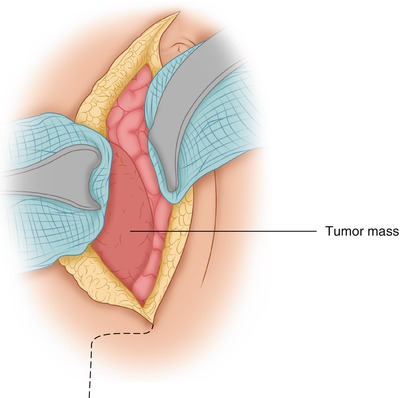

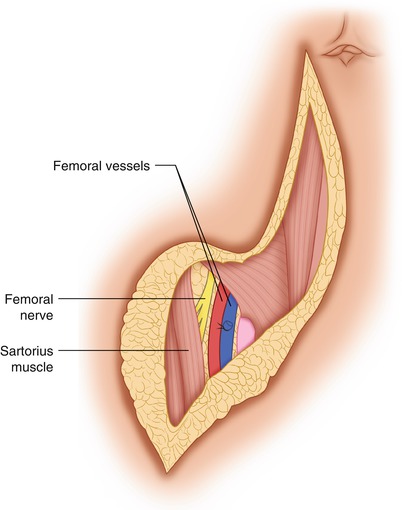

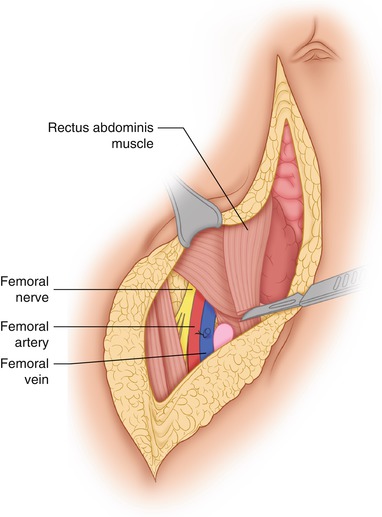

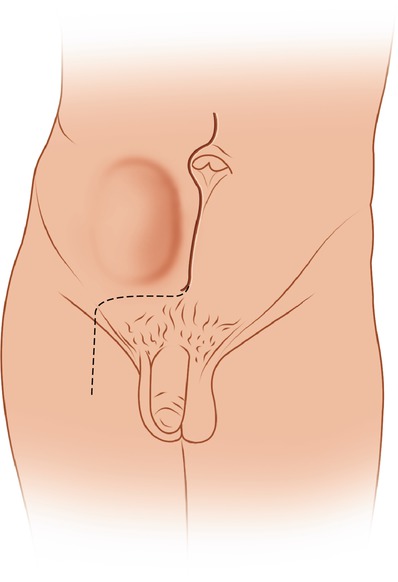

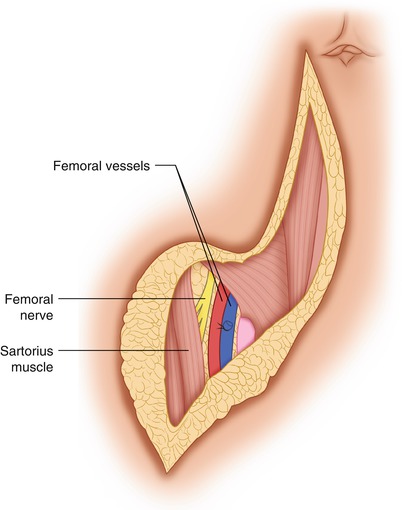

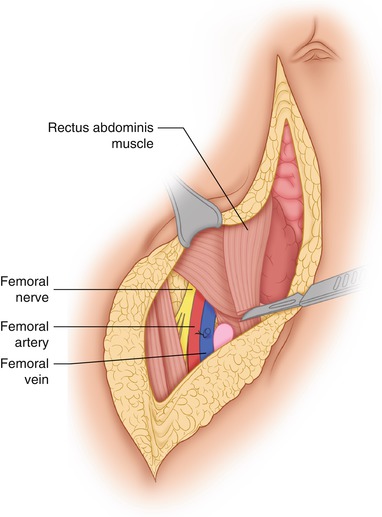

An incision starting in the midline a few centimeters or more above the umbilicus, depending on the proximal extent of the tumor, is carried around the umbilicus on the same side as the tumor and then along the midline all the way down to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 41.2). The linea alba is incised, followed by the peritoneum, allowing exposure of the medial surface of the tumor mass and exploration of the abdomen to search for evidence of metastatic disease to the liver or other sites (Fig. 41.3). Some preliminary dissection may be carried out between the tumor and adjacent loops of small or large bowel. The lower end of the peritoneal incision is continued around the bladder toward the obturator foramen. The skin incision then is extended from the pubic symphysis transversely to the mid-inguinal point on the same side, and then vertically in the femoral triangle for several centimeters, enough to allow exposure of the femoral vessels. The femoral artery and vein are exposed (Fig. 41.4). If exposure of the femoral vein is required further down, one may have to ligate and divide the great saphenous vein at the level of its entry into the femoral vein. The femoral artery is exposed, as well as the femoral nerve, which is found lateral and at a plane posterior to the artery. The rectus abdominis sheath and muscle are divided off the pubic crest (Fig. 41.5).

Fig. 41.2

A lower midline incision extends from just above the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis and then horizontally to the mid-inguinal point on the side of involvement. From this point, it continues vertically in the femoral triangle to allow exposure of the femoral vessels

Fig. 41.3

Through the abdominal part of the incision, the tumor is exposed and a preliminary dissection between the tumor and adjacent structures may be performed. The opportunity for exploration of the abdominal cavity also gives the surgeon a chance to make certain that there is no other metastatic, unresectable disease that might negate the advisability of resecting this tumor

Fig. 41.4

The femoral vessels are exposed in the femoral triangle

Fig. 41.5

The rectus abdominis sheath and muscle are divided off the pubic crest

Dissection of Large Inguinal, Obturator, Iliac Nodes

Although the initial steps of the abdominoinguinal incision are shown above with a large mass in the right iliac fossa, subsequent steps are shown with in continuity dissection of larger inguinal, iliac and obturator nodes which allows a clearer view of the sequential steps of this procedure compared to the dissection of a large mass in the same area.

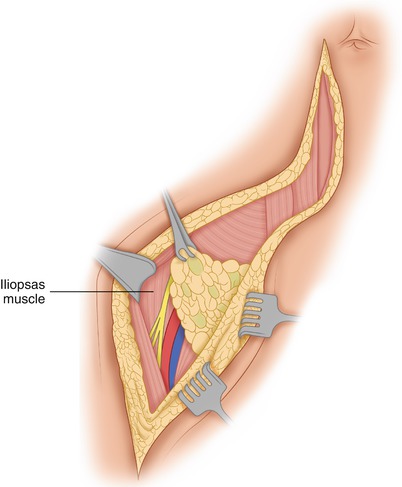

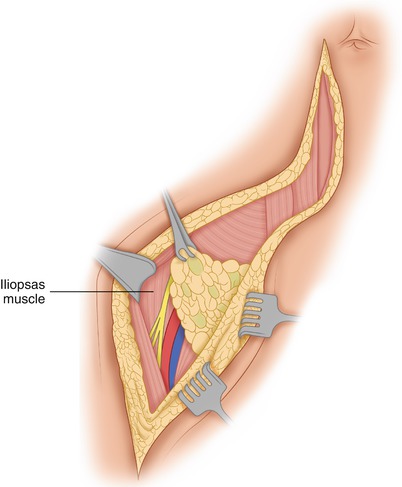

In the case of large retroperitoneal lymph nodes from melanoma or other tumor, which may start in the groin but extend into the external iliac nodal chain—lymph nodes of such size that they cannot be removed through the usual incision for the radical groin dissection—one may use the abdominoinguinal incision. In these patients, the part of the incision that extends into the groin is made longer, to the apex of the femoral triangle, and flaps are developed medially to the medial edge of the adductor longus and laterally to the lateral edge of the sartorius. The inguinal nodes are dissected off the surface of the femoral artery and vein. If dissection of the deep nodes (obturator, iliac) is done through this incision, the lymph nodes in the inguinal area are mobilized and left to be removed in continuity with the lymphatic tissue of the femoral canal and the deep nodes (Fig. 41.6). The inguinal ligament is lifted after it is divided at the pubic tubercle, and the inferior epigastric vein and artery are ligated and divided serially (Fig. 41.7). The lateral third of the inguinal ligament, which is fused with the iliac fascia, is separated from the fascia with care to avoid the deep iliac circumflex artery and vein, which course along the underside of the inguinal ligament in a sheath provided by the edge of the iliac fascia. For a tumor in the iliac fossa, these vessels must be ligated and divided medially as well as laterally. The retroperitoneal space is widely open after the inguinal ligament is separated off the iliac fascia in its lateral third; the inferior epigastric vessels have been divided, the inguinal ligament is detached off the pubic tubercle, and the anterior rectus sheath and muscle is divided off the pubic crest. There is now in continuity exposure of the lower abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, common iliac vessels, external iliac vessels, and femoral vessels on the side of involvement. Any lymph nodes from the area of the obturator fossa are mobilized, exposing the obturator nerve posteriorly (Fig. 41.8). The lymph nodes are dissected off the iliac vessels all the way to the bifurcation of the aorta, and at a higher level if necessary. The ureter is exposed as it courses over the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels, and the specimen is removed after some medial attachments to the adipose tissue around the urinary bladder are divided (Fig. 41.9). In a woman, there is no problem in dividing the anterior rectus sheath and the rectus abdominis muscle off the pubic crest and then continuing to divide the inguinal ligament off the pubic tubercle. In men, however, the spermatic cord is in front of the pubic tubercle in its way to the subcutaneous (superficial) inguinal ring and through the inguinal canal to the internal ring. Therefore, the incision from the superficial inguinal ring is extended in the direction of the fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis for a few centimeters in order to expose the spermatic cord (Fig. 41.10). Then, as the spermatic cord is retracted, the transversalis fascia is incised on the posterior wall of the inguinal canal all the way to the internal inguinal ring (Fig. 41.11), being careful of the inferior epigastric vessels, which course on the medial side of the internal ring and therefore must be ligated and divided. This procedure allows medial displacement of the spermatic cord and preservation of the ipsilateral testicle. The alternative is to divide the inguinal floor from inside, following the division of the anterior rectus sheath and rectus abdominis off the pubic crest and then of the inguinal ligament off the pubic tubercle. In other words, one can expose and incise from inside the transversalis fascia, which forms the inguinal floor, again allowing the medial extrication of the spermatic cord and preservation of the blood supply to the testicle. Deep to the internal inguinal ring, the spermatic cord bifurcates as it separates into its two main components, the vas deferens, which follows a medial direction to the spermatic vesicles, and the internal spermatic artery and vein, which follow a cephalad, slightly medially inclined direction toward their communication with the aorta and inferior vena cava. The internal spermatic artery and vein may be ligated and divided in the retroperitoneal space without affecting the viability of the ipsilateral testicle. Indeed, the spermatic cord also may be divided in the inguinal canal while the viability of the ipsilateral testicle is preserved, as long as one does not separate the testicle off the scrotal skin, from which it receives small blood vessels that are capable of hypertrophy to carry an adequate blood supply to maintain its viability, although some atrophy may occur. After the exposure provided through the abdominoinguinal incision, the resection of the tumor mass with adjacent organs or the dissection of nodes is completed.

Fig. 41.6

When dissection of the inguinal nodes is performed through this incision, flaps are developed medially to the medial border of the adductor longus and laterally to the lateral border of the sartorius muscle, and the nodes are dissected off these muscles and the femoral nerve, as well as the femoral vessels. The nodes are left attached to the femoral canal area so they can be removed in continuity with the deep nodes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree