National, State, and Local Public Health Surveillance Systems

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

2 Tennessee Department of Health, Nashville, TN, USA

Organization and Roles of Public Health Infectious Disease Surveillance Infrastructure in the United States and Steps in the Surveillance Process

State and Local Public Health Organization and Roles

Organization of state, territorial, and local public health entities is varied across the United States. Each state and territory has a department of health (DOH) with legal responsibility for protection of the public’s health, including surveillance, investigation, and control of infectious diseases. States and territories may be further subdivided into regions and local health departments. Regions may consist of individual counties (common in metropolitan areas) or a collection of counties or other geographic subdivisions. In some states, particularly in the Northeast, local or regional areas may be further divided into local boards of health. Local jurisdictions may have additional authorities granted to them by state law. Jurisdictions divided in this way are often referred to as “home rule” states. Some large metropolitan areas (such as New York City) function in the same capacity as a state or territorial DOH and are independent to some extent from the state in which they are located. In some cases, they may even share surveillance data with federal public health authorities directly rather than through the state DOH in which they are located.

Several models for surveillance, investigation, and control responsibilities exist; and some public health jurisdictions have a combination of models. Models can typically be classified into three primary categories: centralized, decentralized, and a combination of both. In centralized models, the state or territorial public health entity coordinates surveillance, investigation, and control efforts at the local, regional and state/territorial levels. In decentralized models, primary investigation and control responsibilities are delegated to local and regional levels with the state serving a coordination and strategic role. Some public health jurisdictions have a combined model. For example, metropolitan areas within the state may carry primary responsibility for surveillance and control whereas these activities in more rural areas may be centralized by the state or territorial authority.

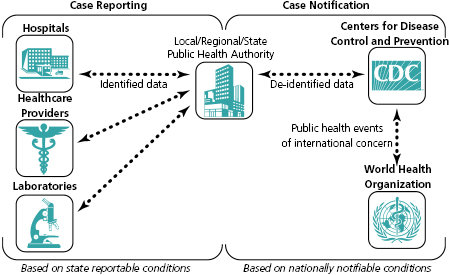

Disease reporting in the United States is mandated by law or regulation only at the local, state, or territorial levels [1,2]. Each state and territory determines which conditions to include on their reportable disease lists; these conditions are designated reportable conditions. Each state and territory also designates who (i.e., healthcare providers, laboratories) is required to report these conditions, what information should be reported, how to report, and how quickly disease information must be reported to public health authorities. The list of reportable conditions varies across states and from year to year. The term case reporting refers to healthcare entities (i.e., healthcare providers, laboratories, and hospitals) identifying reportable conditions and submitting information about these conditions to a local, county, state, or territorial public health agency (Figure 3.1). Individual case reporting requires patient information such as name, address, and phone number. Healthcare entities report suspected or confirmed diagnoses, laboratory tests and results, or information about outbreaks to public health using case morbidity report forms. These report forms can usually be either mailed, faxed, phoned, or submitted electronically. Following submission of the report, public health staff conducts follow-up investigations to confirm the cases based upon the criteria in the surveillance case definition (defined later in this chapter) for the reported disease and identify information needed for prevention and control.

Public health surveillance data are primarily collected at the local public health level where prevention and control activities occur. Then, data are reported in a hierarchical fashion to the regional, state, or territorial health departments. If a condition is considered important at the national level, it is defined as nationally notifiable and the reporting hierarchy continues from the state or territorial department to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (see Figure 3.1 and the section “State-reportable and national notifiable condition surveillance” in this chapter). Table 3.1 lists how each level of public health uses infectious disease surveillance data [3]. Under this system, CDC is not the primary party responsible for public health surveillance; instead, this is the responsibility of local, state, and territorial public health authorities. CDC provides assistance or consultative services to local, state, and territorial health departments in performing and evaluating surveillance as well as in planning and implementing disease control and prevention. For example, CDC plays an important role in developing guidelines (e.g., surveillance system evaluation guidelines) to help assess the adequacy of existing systems [7–12].

Table 3.1 Potential uses of infectious disease surveillance data by level of the public health system.

Source: Adapted from Jajosky RA, Groseclose SL. Evaluation of reporting timeliness of public health surveillance systems for infectious diseases. BMC Public Health 2004; 4:29;1–9. Available from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/4/29.

| Intended uses | Public health system level of use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Identify individual cases or clusters in a jurisdiction to prompt intervention or prevention activities. | Local, state (national) | Meningococcal disease occurring in a college student living in a dormitory requires not only immediate treatment for the patient but also identification of close contacts so that antibiotic prophylaxis can be administered to those potentially exposed. |

| Identify multistate disease outbreaks or clusters. | State, national | In 2011, a multistate listeriosis outbreak was associated with contaminated cantaloupes that had been distributed from a farm in Colorado and associated with infections in 139 people from 28 states [4]. |

| Monitor trends to assess the public health impact of the condition under surveillance. | State, national (local) | After the licensure of the varicella vaccine in the United States, public health monitored the impact of the vaccine to document the decline in disease incidence and to identify whether disease was occurring in fully vaccinated persons. |

| Demonstrate the need for public health intervention programs and resources, as well as allocate resources. | State, national (local) | Surveillance data may identify demographic groups with higher disease incidence than others, which may merit targeted intervention, such as the targeted tuberculosis program for foreign-born residents who have immigrated from countries with high tuberculosis rates [5]. |

| Formulate hypotheses for further study. | National (state) | Surveillance data may suggest an outbreak-specific or previously unknown risk factor associated with a disease, but public health needs to perform a study to ascertain the associations (e.g., Turkish pine nuts and salmonellosis) [6]. |

Note: A public health system level appearing in parenthesis represents secondary use of the data for that purpose.

CDC surveillance systems receive data collected by local, county, state, and territorial public health officials. Data reported to CDC may include information about laboratory tests and results; the healthcare provider’s diagnosis; vaccine history; signs and symptoms recorded by the healthcare entity; as well as demographic data, geographic information, risk factor information, and information about which criteria in the national surveillance case definition was met. No direct personal identifier, such as name, is sent to CDC. Data that are shared with CDC are a subset of the data collected and used by local or state level, including data collected during public health investigations to determine if public health intervention is appropriate and to further make the determination if a suspected case meets the surveillance case definition(s).

Public health surveillance case definitions may include combinations of clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory criteria used to define what a “case” of disease is for surveillance purposes. These definitions enable public health to classify and enumerate cases consistently across reporting jurisdictions. National case definitions are used by states and territories to guide what data are sent to CDC in a case notification, to ensure CDC aggregates data across reporting jurisdictions consistently. States and territories may adopt national surveillance case definitions for use within their jurisdictions or may develop additional case definitions for surveillance or outbreak purposes. Surveillance case definitions are not intended to guide healthcare providers in making medical decisions about individual patients [13].

Surveillance Process Roles and Responsibilities

The primary purpose of public health surveillance for infectious diseases is to identify problems amenable to public health action aimed at controlling or preventing disease spread. When a potential case of infectious disease is identified through surveillance activities, the response will vary depending on the disease as well as other factors. For example, whether further investigation into the suspected case is undertaken depends on many factors, including but not limited to likelihood of transmission, availability of effective interventions, severity of the disease and public health impact, local and state priorities, and available resources. Once the decision is made to perform a public health investigation, additional data are usually collected. An investigation may be as simple as a phone call to the physician who provided the case report, or it may involve other actions such as performing an inspection at a facility that may be the site of exposure, as well as extensive interviews with multiple individuals.

Public health investigation processes vary across jurisdictions. Typically, a laboratory report or a report of a suspected case of disease is identified, either through passive or active surveillance systems, and triggers the investigation process. Note, however, that not all reports of suspected cases trigger further investigation. Public health staff conducting the investigation will collect clinical, epidemiologic and laboratory data from multiple sources and combine them to confirm the case and determine which public health actions are needed. The investigation may be completed by a single person (such as a public health nurse) or by a multidisciplinary team (common with outbreak investigations), which may consist of a public health physician and nurse, an epidemiologist, an environmentalist, a laboratorian, a veterinarian, or another specialist. If the investigation is part of an emergency response effort, law enforcement, emergency management officials, and other partners outside core public health may be involved in the investigation. During an investigation, data may also be exchanged across jurisdictional boundaries (such as across states). Other entities (such as CDC, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or United States Department of Agriculture for a multistate foodborne outbreak) may also need to be engaged, depending on the type of investigation.

Control of disease spread is achieved through public health actions. Public health actions resulting from information gained during the investigation usually go beyond what an individual physician can provide to his or her patients presenting in a clinical setting. Examples of public health actions include identifying the source of infection (e.g., an infected person transmitting disease or a contaminated food vehicle); identifying persons who were in contact with the index case or any infected person who may need vaccines or antiinfectives to prevent them from developing the infection; closure of facilities implicated in disease spread; or isolation of sick individuals or, in rare circumstances, quarantining those exposed to an infected person.

Analysis and Use of Surveillance Data

Monitoring surveillance data enables public health authorities to detect sudden changes in disease occurrence and distribution, identify changes in agents or host factors, and detect changes in healthcare practices [1]. An example of a change in healthcare practice is the increasing use of nonculture-based testing (e.g., enzyme immunoassay for campylobacter) to verify the etiologic organism responsible for an infection. It is important to understand how changes in testing practices affect surveillance and laboratory criteria for surveillance case confirmation. Public health officials need to review new laboratory testing methods to help guide analysis and interpretation of data.

The primary use of surveillance data at the local and state public health level is to identify cases or outbreaks in order to implement immediate disease control and prevention activities. CDC works collaboratively with states to identify and control multistate disease outbreaks. Surveillance data are also used by states and CDC to monitor disease trends, demonstrate the need for public health interventions such as vaccines and vaccine policy, evaluate public health activities, and identify future research priorities. See Table 3.1 for a description of how surveillance data are used by all levels of public health.

CDC routinely aggregates and analyzes data across reporting jurisdictions and shares the analytical results with the data providers [1,14–16]. Analyses of public health surveillance data on nationally notifiable conditions enables public health authorities to monitor disease trends, assess the effectiveness of prevention and control measures, identify high-risk populations or geographical areas, allocate resources appropriately, formulate prevention and control strategies, and develop public health policies [1,2,17].

One example of an analysis CDC performs weekly on aggregated provisional data reported to CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) represents the application of the historical limits aberration detection algorithm, run at the national level and published as Figure I in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) [18]. This method compares the number of cases reported in the current 4-week period for a specific disease with the historical mean for that disease. The historical mean is based on the cases reported for 15 4-week periods comprised of the previous, comparable, and subsequent 4-week periods for the past 5 years. This analysis assists epidemiologists in identifying departures from past disease reporting patterns, which may require further investigation. CDC subject matter experts also monitor the provisional surveillance data on a weekly basis, comparing current case counts with incidence for the same time period in past years in order to detect changes in reporting patterns which may merit further study or investigation.

State Reportable and National Notifiable Condition Surveillance

Many reportable conditions are designated by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) as being nationally notifiable [1,19]. CSTE is an organization that represents the collective public health interests of state and territorial epidemiologists. Figure 3.1 illustrates the components of surveillance data flow that relate to public health case reporting within states and territories and those that relate to case notification from state or territorial health departments to CDC for Nationally Notifiable Conditions (NNC). Annual changes to the list of infectious (and noninfectious) NNC, as well as new and revised national surveillance case definitions, are decided upon and implemented through CSTE.

The official CSTE NNC list classifies the conditions according to the time frames in which CDC should be notified [19]. Three categories of time frames for case notification exist; these include immediate extremely urgent, immediate urgent and standard notification. Data on each of these three notification categories use the same electronic submission protocol, although they differ in terms of the recommended timeliness for each category of case notification [20]. In addition, the protocol for the two immediate notification categories includes a step requesting an initial voice notification to CDC’s Emergency Operations Center in order to facilitate timely communication about details and circumstances of the event between subject matter experts in the state or territory and CDC. A subset of NNC case notifications may be notified to the World Health Organization (WHO) as per the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) because of the potential for a public health emergency of international concern (see Figure 3.1) [21]. In the United States, the CDC notifies the Department of Health and Human Services, which submits events under IHR to the WHO.

When proposing revisions to the list of NNC, CDC, and CSTE collaboratively consider the goals, purposes, and objectives of surveillance, as well as factors such as incidence (how frequently new cases of the condition occur in the population); severity of the condition, such as the case-fatality rate; communicability (how readily the disease is spread); preventability; impact on the population or community; and need for public health action. The CSTE recommends that all states and territories enact laws or regulations making NNC reportable in jurisdictions [22]. State and territorial health departments voluntarily submit data about NNC to CDC. The term case notification refers to the submission of electronic data by states and territories to CDC about nationally notifiable disease cases (see Figure 3.1 and Table 3.2). This differs from case reporting, which represents reporting of identifiable information from health care, laboratories, and other reporting entities to local/state/territorial public health in accordance with reporting laws and regulations (see Figure 3.1 and Table 3.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree