Practical Considerations in Implementation of Electronic Laboratory Reporting for Infectious Disease Surveillance

1 Department of Epidemiology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

2 Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, PA, USA

Introduction

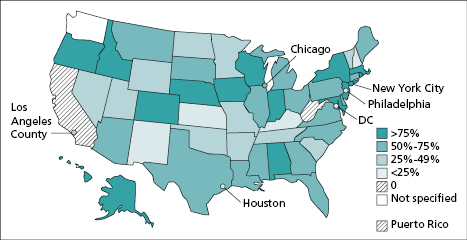

A primary objective in infectious disease surveillance through case reports is to trigger an appropriate public health response so that further illness can be prevented and public fears allayed [1]. Increasing timeliness and completeness of reporting are essential to achieving these objectives. Reporting to public health agencies of laboratory results indicative of the presence of a case of a reportable disease has been an important surveillance method in most states since the 1980s; 49 states had at least some laboratory reporting requirements by 1999 [2]. During the past decade, increasingly widespread use of electronic information systems by clinical laboratories enabled public health officials to receive these reports much more quickly, completely, and accurately [3]. By mid-2013, 54 of the 57 jurisdictions responsible for conducting surveillance (48 state and six large local health departments) were receiving at least some laboratory reports through electronic laboratory reporting (ELR) (Figure 19.1). Participation of clinical laboratories in ELR, however, remains suboptimal. Based on a 12-month estimate, approximately 62% of 20 million reports were submitted to the 54 public health jurisdictions via ELR in 2013 [4].

To enhance public health surveillance, ELR is included in the recent federally led initiative to transform healthcare delivery through incentives for meaningful use of ELR [5]. These incentives are expected to accelerate adoption of ELR by hospital laboratories. Implementation of ELR, however, is complex; a recent evaluation of the status of deployed ELR systems suggests a need for improvements in integrating data for diseases that have a high volume of laboratory reports (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases) [4]. This chapter focuses on the practical considerations for implementation of ELR including the development process and potential practical challenges. As an illustrative example, the chapter discusses experiences and lessons learned in implementation of ELR in Florida.

The Role of Clinical Laboratories in Surveillance

Case definitions for Nationally Notifiable Diseases

The role of clinical laboratories in infectious disease reporting has evolved over time, and it became increasingly important after the 1990 adoption of public health surveillance case definitions for nationally notifiable diseases by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Case definitions established uniform criteria, including specific laboratory criteria, for classifying (e.g., probable or confirmed) and counting cases consistently across jurisdictions [6].

Laboratory criteria are essential in some (e.g., meningococcal disease; hepatitis A, B, and C; salmonellosis; tuberculosis; gonorrhea; and campylobacteriosis) but not all surveillance case definitions. Diseases and conditions under public health surveillance change with clinical knowledge, advances in laboratory diagnostic technology, and changes in infectious disease incidence, as do case definitions. The CSTE annually adds or subtracts diseases from the list of Nationally Notifiable Diseases [7] and updates case definitions through position statements considered and adopted by its members [8]. For example, the HIV/AIDS surveillance case definition, first published in 1997, has undergone multiple revisions in response to improvements in diagnostic methods (see Chapter 12 for detailed discussion on HIV/AIDS including the evolution of the case definition).

Although each jurisdiction has its own list of reportable diseases, CSTE encourages all jurisdictions to submit data on nationally notifiable diseases to CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) [7]. The data in NNDSS allows public health jurisdictions to monitor their progress in meeting objectives for programs funded through CDC Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases (ELC) Cooperative Agreement. ELC grants support programs that focus on specific areas (e.g., foodborne diseases), and they support infrastructure for conducting surveillance. These grants are awarded to all jurisdictions that directly report data to NNDSS, and the local health departments in the six largest cities (e.g., Los Angeles County and Philadelphia) [9]. (See Chapter 3 for a fuller description of NNDSS and national, state, and local public health surveillance systems.) Studies conducted in jurisdictions that were leaders in requiring electronic laboratory reporting in the late 1990s document an increase in timeliness and completeness of case reporting when compared to passive reporting by physicians and laboratories [10,11].

Mandatory Reporting by Clinical Laboratories

For decades, public health officials have recognized the need to mandate disease reporting from a variety of sources. For example, an evaluation of a communicable diseases surveillance system in Vermont in the mid-1980s identified a need to mandate reporting by clinical laboratories. Aware of possible misinterpretation, the study cautioned that mandatory reporting by clinical laboratories would not “eliminate physician’s legal responsibility to report disease” [12]. Comprehensive surveys conducted since the mid-1990s by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists indicate that most diseases designated as nationally notifiable are reportable in most NEDSS jurisdictions by both clinical laboratories and physicians. For example, in 2010 laboratory evidence of anthrax was reportable in all 50 states and the District of Columbia; laboratory evidence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection was reportable in 50 of these 51 jurisdictions; cyclosporiasis in 41; and babesiosis in 17 [13].

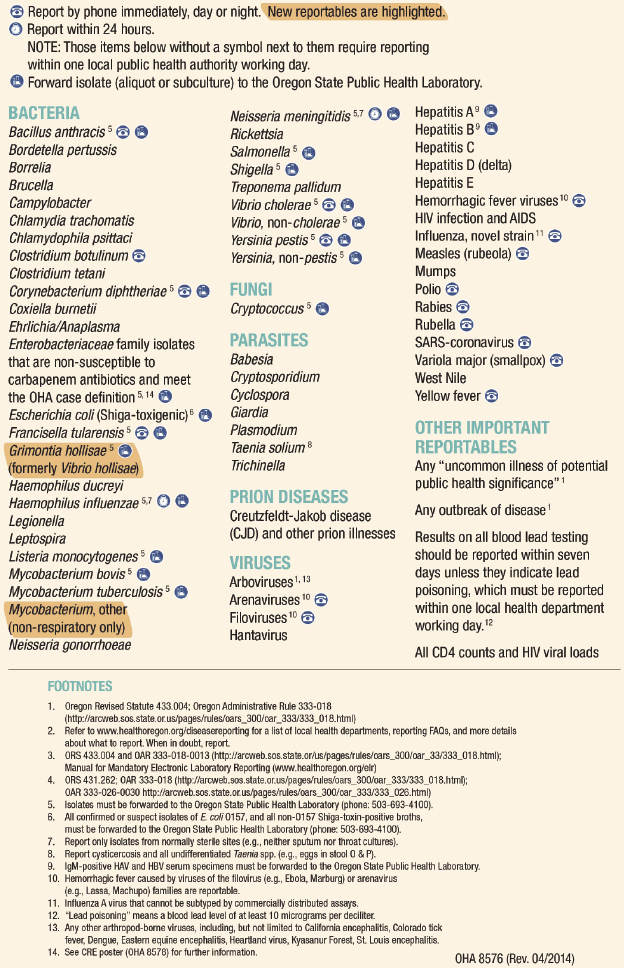

Public health reporting requirements vary by jurisdiction. Some provide a single list with distinct requirements for healthcare providers and clinical laboratories, whereas others have a separate list of requirements for clinical laboratories [14,15]. These requirements explicitly specify a timeframe for reporting specified conditions. Maryland’s list, for example, includes a category for conditions that necessitate immediate reporting (e.g., Bacillus anthracis) and a category for other conditions that are reportable within one working day (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes). In addition to an explicit requirement for immediate reporting by telephone for specified conditions (Figure 19.2), Oregon law requires clinical laboratories that report an average of >30 records per month to the local public health authority to submit data through ELR.

For specific diseases, many jurisdictions require that laboratories submit an isolate or a specimen to the state public health laboratory for confirmation and additional characterization. Wyoming, for example, requires that clinical laboratories submit isolates or other appropriate material indicative of certain conditions specified on a list of reportable diseases and conditions [16]. To facilitate surveillance and epidemiological investigations, laboratories are often required to include patient information (e.g., first and last name, date of birth, sex, home address) in their case reports. Additional information includes type of specimen (e.g., stool, urine, blood), collection date, test performed, and results. Details about the submitting provider (e.g., name and address) are also required. Some jurisdictions make information on what is reportable easily accessible by providing confidential case report forms on their websites [17].

Benefits and Challenges in Implementation of Electronic Laboratory Reporting

Electronic Laboratory Reporting Benefits to Surveillance

Attributes of surveillance systems are described in detail in the Updated Guidelines for Evaluating Public Health Surveillance Systems [18]. ELR can result in increased timeliness, sensitivity, positive predictive value, and acceptability (Box 19.1). When implemented effectively, ELR should result in more rapid reporting of cases requiring public health action and should facilitate tracing of contacts and provision of antimicrobial prophylaxis. Based on evidence from deployed systems, electronic case reports arrive approximately 4 days earlier than those from a paper-based system [10]. The benefits of receiving timely test results, however, depend on the necessity to initiate public health response. For example, if positive test results of organisms typically associated with outbreaks (e.g., Salmonella species) are received in a timely manner, this can trigger an investigation. ELR also provides documentation for conditions that are reportable by telephone (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes) [14].

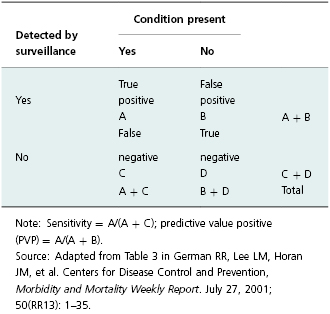

Increased sensitivity in this context refers to the ability of the system to ensure that reports are made for all positive test results (Table 19.1). When fully implemented, ELR systems are at least as sensitive as conventional paper-based systems [19,20]. Sensitivity is significantly higher for reports received through ELR for those diseases whose diagnosis requires laboratory testing (e.g., Chlamydia trachomatis) [11]. In addition, ELR systems typically result in higher positive predictive value (PPV). This concept in surveillance means that reported cases are more likely to represent true cases (Table 19.1). ELR systems can have high PPV for diseases that have laboratory tests that are specific with only rare false positives (e.g., culture for enteric organisms) [21]. Additionally, reduction in manual data-entry errors increases accuracy of case reports [19].

Table 19.1 Calculation for sensitivity and predictive value positive for a surveillance system.

Resource Needs and Challenges in Implementation of Electronic Laboratory Reporting

For clinical laboratories with automated information systems that offer electronic services such as order entry forms and results reporting to providers, ELR can be relatively inexpensive. The cost for software to extract reportable conditions from an existing system was estimated at $40,000 in Indiana [22], which would be reasonable given the relatively high cost of laboratory information systems. In some cases, however, data extraction and messaging with an existing laboratory information system may be difficult. Building an information system to capture reportable conditions from a wide of array of test types (e.g., microbiology, virology, parasitology) is a challenge for small clinical laboratories in hospitals. Typically, ELR messages must comply with specific information technology (IT) standards [23]. To offset the cost of participation in ELR, including cost for complying with these standards, qualified hospital facilities can take advantage of monetary incentives available through the EHR Incentive Program to offset the cost of adapting ELR [5].

In addition to monetary costs, clinical laboratories may encounter other barriers to implementation of ELR. Clinical laboratories may be unaware of reporting requirements, specifically what and how to report. To address this well-known barrier, jurisdictions provide guidance for electronic laboratory reporting [24]. Experience from New York City and elsewhere, however, suggests that in addition to guidance, there is a need for regular communication between public health officials and individuals who are responsible for reporting in clinical laboratories [20]. Transfer of electronic messages with reportable disease data can also present a practical challenge to clinical laboratories. Although approaches used to submit electronic data to public health authorities vary, laboratories are expected to comply with criteria set by public health authorities in each jurisdiction. Typically, laboratories identify reportable conditions in their test catalog and then map them into standard codes acceptable to the respective public health jurisdiction (Box 19.2). The codes used are typically LOINC and SNOMED, which respectively refer to Logical Observation Identifiers Names, Codes, and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [25,26]. Receipt of nonstandardized data is one of the main reasons for delays in automated processing of ELR cited by public health jurisdictions [27]. Recently, an ELR working group created an updated reportable condition–mapping table to facilitate extraction of LOINC and SNOMED codes for nationally notifiable diseases by clinical laboratories [28].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree