Lessons Learned in Epidemiology and Surveillance Training in New York City

1 Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA

2 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Queens, NY, USA

Introduction

Infectious disease surveillance is a complex and continuously evolving practice, requiring coordinated efforts of highly trained public health professionals. Early in the 1900s, as the first schools of public health were established in the United States, early leaders in public health education recognized the value of field experience as a counterpoint to coursework. In 1915, the Rockefeller Foundation published the seminal Welsh-Rose report, which called for the close collaboration of these schools with local, state, and federal agencies to ensure adequate training of future health professionals [1]. The New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) was an ideal setting for such collaboration because of its history of innovation, including controlling cholera and typhus by using the first municipal laboratory to test and quarantine passengers arriving by ship into New York Harbor in the 1890s. Other innovations included controlling diphtheria by providing free antitoxin to the poor in 1906 and initiation of the largest-ever rapid vaccination campaign to thwart a smallpox epidemic in 1947 [2].

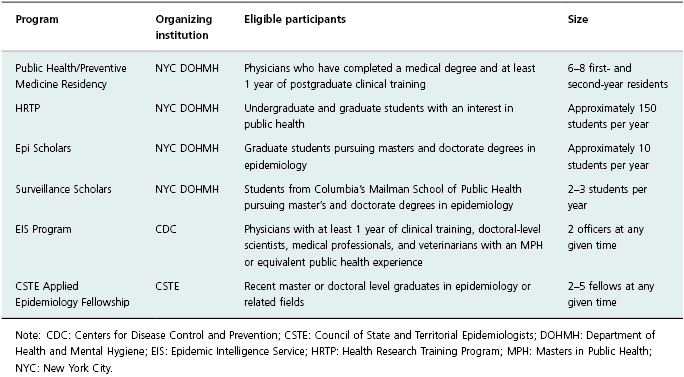

DOHMH currently runs four formal training programs. The Public Health/ Preventive Medicine Residency Program is a 2-year postgraduate training program for physicians. The Health Research Training Program (HRTP) provides year-round field opportunities in public health for undergraduate and graduate students from a variety of disciplines. The Epi Scholars Program is a summer internship in applied public health research for graduate students in epidemiology, and the Surveillance Scholars program offers summer internships in applied surveillance to graduate students at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health (MSPH). In addition to running local training programs, DOHMH hosts trainees from national public health training programs including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists’ (CSTE) Applied Epidemiology Fellowship (Table 22.1).

Table 22.1 Formal training programs available at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The shifting of public health priorities over time continues to offer compelling training experiences: fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic since the 1980s, controlling a resurgence of tuberculosis in the 1990s, identifying risk factors for chronic diseases, and preparing for bioterrorism threats in the twenty-first century. Even as the increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases has led to seismic changes in public health priorities [3], the DOHMH has recognized the imperative to maintain the capacity to conduct rigorous infectious disease surveillance. Field experience at DOHMH allows all trainees to begin to appreciate the rewards and challenges of conducting public health surveillance at the local level and inspires many to pursue careers in applied public health.

The Public Health/Preventive Medicine Residency Program: Training Physicians in Public Health Theory and Methods

The Public Health/Preventive Medicine Residency Program, originally accredited in 1959, is one of the oldest such programs in the country [4]. The residency works in partnership with the MSPH at Columbia University, which enables residents to obtain a Masters in Public Health (MPH) degree during their 2 years of residency training. The aims of the program are to train physicians in health promotion and disease prevention on a population level and to develop leaders in epidemiological and clinical research, public health practice, and clinical preventive medicine. Applicants to the program must have completed a medical degree and at least 1 year of postgraduate training in a clinical residency program.

Residents are expected to gain competency in conducting surveillance; analyzing data; planning, implementing, and evaluating disease prevention and control initiatives; communicating with the public, policymakers, and health-care providers; promoting health and preventing disease in healthcare institutions and the community; and formulating policy [5]. Residents gain these competencies through a combination of hands-on experience, observation and didactic sessions. While they are enrolled in the MSPH master’s program during both years of residency, they conduct several short-term projects in various work units of the DOHMH during the first year and complete a year-long practicum during the second year.

Examples of Surveillance Activities

The DOHMH provides unique opportunities for residents to participate in infectious disease surveillance projects. For example, the DOHMH initiated the Primary Care Information Project (PCIP) in 2005, which allows the department to receive de-identified aggregate data from primary care practices that have adopted electronic health record systems with the department’s assistance. One resident piloted a project to link laboratory-confirmed influenza cases with outpatient visits for influenza-like illnesses. She coordinated with four PCIP primary care sites to collect data and specimens from patients with influenza-like illness. Specimens were analyzed in the DOHMH public health laboratory by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the presence of influenza virus. The resident ensured accurate data collection, reported aggregate data to the CDC weekly, and distributed weekly epidemic curves for use by the DOHMH.

Residents also have the opportunity to work with many of the rich data sets available at the DOHMH, including NYC’s Citywide Immunization Registry (CIR). One resident used the CIR to determine the geographic distribution of underimmunized children. Initiated in 1997, the CIR combines birth information from vital records with mandatory vaccine administration reports from pediatric providers. The resident used the data in the CIR to map immunization coverage by zip code using geographic information systems (GIS). She identified the 10 zip codes with the lowest immunization coverage for targeted outreach by the DOHMH.

Residents also have the opportunity to lead at least one outbreak investigation and to participate in tuberculosis contact investigations. One resident completed a practicum project on a tuberculosis cluster investigation. Since 2001, the DOHMH has used genotyping to enhance cluster investigations and to distinguish between reactivation and exogenous reinfection. Using genotyping, the resident was able to show probable transmission of tuberculosis within NYC in 2009, which informed the activities of the Bureau of Tuberculosis Control.

Many other resident projects have involved aspects of infectious disease surveillance and epidemiology. Two residents assisted on a quality improvement project for cause-of-death reporting on death certificates. As a result of this project, overreporting of heart disease deaths and underreporting of other causes of death including pneumonia and influenza were corrected [6]. This helped residents understand the importance of monitoring the quality of data sources for surveillance. Another resident created a report on the epidemiology of meningococcal disease in NYC, and one resident used hospital discharge data to document the rising incidence of community-onset, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

The on-Call Experience

Residents spend time on call for the DOHMH on some weekends and evening hours, allowing them to experience first-hand how to respond to a wide variety of questions and reports that the health department receives from the provider community. On-call experiences frequently allow residents to participate in the initial response to an outbreak. In 2001, a resident was on call when the first case of cutaneous anthrax was reported to the DOHMH and was able to participate in the earliest stages of the investigation. During the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, when providers began to report multiple cases of influenza, an on-call resident assisted in collecting and recording information for analysis by the swine flu investigation team. These activities gave residents experience in communicating during public health emergencies, and they demonstrated the role of the local health department in high-profile infectious disease control.

In addition to learning from hands-on experience, there are numerous formal and informal didactic opportunities for residents. Residents are required to take introductory epidemiology and biostatistics courses for their MPH degree and some elect to take advanced infectious disease epidemiology coursework. Coursework often directly informs the residents’ ongoing work at the DOHMH, and residents choose elective courses that build the necessary skill sets to complete their practical experience. In addition, the residency holds weekly formal didactic sessions that include journal club, presentations of public health topics by outside speakers and preparation for certification tests. Residents are encouraged to attend the DOHMH Division of Epidemiology grand rounds and methods seminars in the Bureaus of HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis Control where they learn how data are interpreted and used and see first-hand how surveillance data influence activities of the department.

Lessons Learned

The success of the residency program is dependent on the development of projects that meet residents’ interests and skill sets and that complement their coursework while fostering professional competency. Projects must be feasible with respect to time and resources available. Public Health/Preventive Medicine Residents must balance a full-time MPH course load with their work at the DOHMH and are not always available to work daily on time-sensitive projects such as outbreak investigations. Residency directors have learned to carefully screen projects for feasibility and ensure that preceptors document the expected time commitments for projects carefully prior to accepting the project.

The residency director collaborates closely with the MSPH to ensure that residents take appropriate courses that build the skill sets necessary for successful completion of their projects. This requires regular communication as curricula and course content are frequently updated. Funding for resident stipends must be pursued. For example, since 2004, one resident per year has been funded through a grant from the American Cancer Society.

Program Impact

Several graduates of the public health/preventive medicine residency program currently serve in leadership positions within DOHMH. Others have gone on to work for other local health departments, international nongovernmental organizations, academic medical centers, public hospitals and schools of public health [5]. Some graduates return to clinical medicine where they may be more likely to participate in public health initiatives and to apply population health principles in their practices.

The Health Research Training Program: Fostering Interest in Public Health across Disciplines:

Building on the success of the Public Health Preventive Medicine Residency, HRTP was created in 1960 in order to include undergraduate and graduate students from a variety of disciplines. The current aims of the program are “to orient students to the principles and practices of public health planning, policy, research, administration and evaluation; to broaden students’ concept of public health by increasing their awareness of needs, challenges and career opportunities in the field; and to assist the DOHMH in recruiting skilled, professional candidates with proven potential” [7]. HRTP accepts about 30 part-time interns for each of the fall and spring sessions, and 70–100 full-time interns for the summer session. Applicants are undergraduates in any field and graduate students from varying disciplines including public health, nursing, and occasionally even law school.

HRTP interns participate in applied public health projects and didactic sessions. Eligible projects are those that will develop core public health skills such as data collection, data analysis, survey design, health promotion, community health outreach, program planning, and evaluation. The summer weekly didactic sessions provide a robust curriculum and are taught by DOHMH staff members who volunteer their time. Lectures cover the agency’s priority public health initiatives. Workshops include SAS statistical software training, program evaluation and GIS. Additionally, interns are invited to attend a career panel comprised of a diverse group of public health professionals. Some students attend staff, agency, and citywide task force meetings that give them a better understanding of the scope of local public health work. HRTP also promotes networking among interns through an interactive orientation, a midsummer feedback session and other events.

Examples of Surveillance Activities

In recent years, the number of projects involving noncommunicable diseases has increased, yet the DOHMH continues to offer numerous infectious disease–related training opportunities. One HRTP intern has been involved in maintaining the DOHMH’s hepatitis A database. Other HRTP interns have contributed to the DOHMH’s enhanced surveillance for salmonellosis. The DOHMH uses the Minnesota protocol under which a centralized team conducts rapid assessment of effected individuals using hypothesis-generating telephone interviews as soon as possible after cases are reported through NYC laboratories to the DOHMH. In order to reach cases quickly during foodborne outbreaks, interns conduct patient interviews both during and after regular business hours. Interns also develop databases for data entry, clean and analyze the data, and write outbreak reports. These experiences allow interns to understand how surveillance systems operate from case identification through analysis to data dissemination.

Lessons Learned

Formalizing and centralizing the internship experience through HRTP has significant benefits for both interns and the DOHMH. HRTP staff members identify and recruit exceptionally skilled and dedicated preceptors. HRTP monitors the quality of intern projects by requiring potential preceptors to submit a project summary that is explicit about the skills the trainee will bring to the project and the skills the trainee will develop. In addition, providing a formal didactic curriculum allows interns to make connections between their course work and practical experience.

Having a centralized program also makes it easier for programs to bring in high-quality interns, because the formal, rigorous application and selection process for all trainees is standardized and handled by HRTP staff. HRTP encourages paid internships, because this allows the DOHMH to recruit talented interns who might not otherwise be able to participate due to financial constraints.

Program Impact

HRTP is a highly successful program. In 2011, the department contacted 343 HRTP alumni for whom contact information was available. Of the 238 (69%) who confirmed participation in HRTP and responded to questions about their experience, the vast majority indicated that HRTP had assisted them in their educational goals (94%) and their career goals (90%); 95% stated that HRTP had positively influenced their career. Of the 178 (52%) who answered questions related to employment, 74% were employed in a public health agency, 59% were employed in the local public health setting, and 37% had been employed at DOHMH at some point in their career after completing HRTP [8].

Because of the program’s longevity, professionals at the DOHMH are familiar with HRTP and are experienced in initiation of discrete projects that benefit both the intern and the program. Since many HRTP interns have subsequently been hired by DOHMH, these graduates of the program serve as ideal mentors for new students. Many DOHMH projects are only completed because of the availability of highly motivated HRTP interns. HRTP is a model for successfully integrating field training into public health education.

The Epi Scholars Program: Providing Hands-on Training for Future Epidemiologists

The World Trade Center and anthrax attacks of 2001 led to a renewed national interest in investing in public health infrastructure, setting the stage for expanding training [9]. In 2007, DOHMH secured funding from the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation to launch the Epi Scholars Program. This program accepts graduate students in epidemiology to work closely with a mentor at the DOHMH on an analytic project during a 12-week paid summer internship. The program aims to cultivate leadership in applied epidemiology, to advance public health research at DOHMH and other participating health departments, to provide applied public health research experience to epidemiology graduate students, and to attract graduate epidemiology students to public health as a career choice [10].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree