Infectious Disease Surveillance and Global Security

1 Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA

2 Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Columbia, MD, USA

Introduction

Current State of Global, Regional and National Disease Surveillance

The World Health Organization (WHO) serves as the universally recognized steward for global health with a mandate from the United Nations (UN) and all 195 member states to coordinate global health efforts including disease surveillance and outbreak detection and response [1]. The WHO relies on numerous tools to implement its mission, including binding treaties such as the International Health Regulations (IHR) [2]. The new guidelines were significant in that they increased the visibility of public health within the greater global foreign policy and diplomatic communities. Despite unanimous agreement to comply with the IHR, most UN member countries do not yet have the capability to detect, analyze, report, and respond to an outbreak of a disease with the potential to spread globally, commonly referred to as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [2]. To date, only 30 member states have claimed the full capacity to comply with the IHR [3].

In 2000, WHO created an operational response unit called the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) with the primary goal of improving global health security [3]. The WHO itself does not possess the numbers of technically trained personnel that would be required to meet this goal, so it relies on a voluntary network of institutions and personnel organized through the GOARN operational framework. The GOARN works to prevent the international spread of epidemics by assuring that the correct technical expertise is provided to a location in need in a timely fashion helping to build sustainable response capacities on the local level. Members of the GOARN include laboratory networks, scientific institutions in UN member states, surveillance networks, UN organizations such as UNICEF, and medical nongovernmental organizations such as Medecins sans Frontieres. The GOARN has established Guiding Principles that describe expectations for preparedness and response to epidemics, as well as procedures that attempt to standardize operations. The GOARN network has demonstrated its effectiveness in responses to over 50 events in 40 countries, including the SARS epidemic, H5N1 avian influenza outbreaks, and several cholera outbreaks around the world [4].

The WHO’s headquarters is located in Geneva, Switzerland, but many public health activities are delegated to regional offices. These regional offices are: the Regional Office for the Americas, also known as the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), in Washington, DC, United States; the Regional Office for Europe (EURO) in Copenhagen, Denmark; the Regional Office for South-east Asia (SEARO) in New Delhi, India; the Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO) in Manila, Philippines; and the Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO) in Cairo, Egypt [1]. The capability of these regional offices depends on the commitment of the countries in the region and their relationship with WHO headquarters.

A limited number of organizations with financial resources and regional governance structures that allow for such activities also conduct regional disease surveillance. Among these are the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the Asia Pacific Economic Council’s Emerging Infections Network (APEC EIN) [5,6]. The ECDC was established in 2005 by the European Union to strengthen defenses against contagious infectious diseases in Europe through comprehensive disease surveillance and early response to potential threats. In addition to surveillance and response activities, ECDC provides timely and relevant data and technical expertise to the Europe Union countries. The ECDC was crucial in the response to the recent outbreak of Escherichia coli O1:O4 that led to hemolytic uremic syndrome in Europe because of contaminated food. Other regional networks such as APEC EIN are less formalized and more narrowly focused on emerging infections and their impact on trade [6].

Role of the Military in Global Infectious Disease Surveillance

Other organizations with longstanding interest in disease surveillance are the world’s militaries. Timely detection of new diseases and epidemics is important to for protection of service members. It is also a key requirement for global public health security, increasingly recognized as crucial to stability. Timely detection of disease outbreaks requires adequate infectious disease surveillance, the ability and willingness to report to global public health authorities, and a meaningful mechanism for providing response to control an outbreak. The global presence of militaries in support of peacekeeping or strategic missions makes these requirements even more relevant for the military, especially when reporting of potential disease outbreaks among personnel in a foreign country is required. Additionally, military, government, and nongovernmental personnel dispatched around the world have a special responsibility to prevent the spread of contagious diseases through their travels. In the past, militaries have inadvertently contributed to the spread of infectious diseases, including influenza during the 1918–1919 pandemic and, more recently, cholera in Haiti [7]. Because of this reality and the recognized responsibility to the overall public health, militaries continue to make significant contributions to global infectious disease surveillance efforts, often in direct support of the IHR mission [8]. As discussed later in this chapter, the United States Department of Defense supports development of electronic systems to facilitate disease reporting within partner host countries [9].

U.S-Based Global Disease Surveillance

Global Disease Detection Program

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a major role in disease surveillance and response throughout the world. Initially charged with a domestic responsibility, CDC over time has developed an increasingly global presence. The Global Disease Detection Program and Emergency Response (GDDER), begun in 2004, is CDC’s lead initiative for developing and strengthening global capacity to rapidly detect, accurately identify, and promptly contain emerging infectious disease and bioterrorist threats that occur internationally [10]. The GDDER was created to “mitigate the consequences of a catastrophic public health event, whether by an intentional act of terrorism, or the natural emergence of a deadly infectious virus” [10].

CDC approaches its mission of improving global health security through building cooperative partnerships. The GDDER program was designated as the first WHO Collaborating Center for Implementation of International Health Regulations, National Surveillance and Response Capacity [10]. In this role, the GDDER program partners with Ministries of Health, WHO, and already established CDC programs to improve core public health capacities in developing countries targeting early identification and control of emerging infectious diseases. Some of these established programs include the influenza surveillance network, field epidemiology and laboratory training programs emerging infections and zoonotic disease surveillance, laboratory strengthening and capacity building, and risk communication and emergency response.

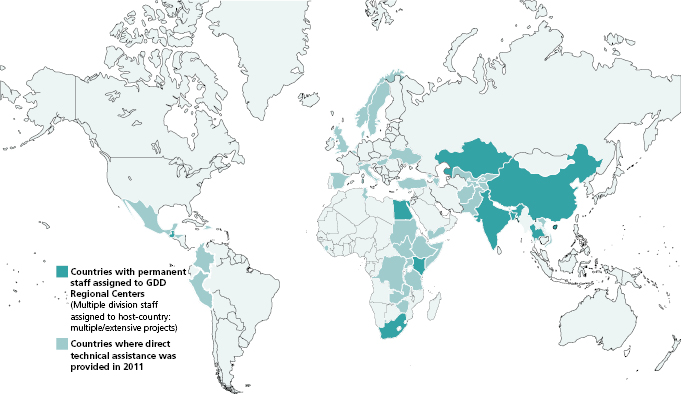

The GDDER program has centers throughout the world that are located in places where their expertise may be maximally leveraged by the host countries and regions (Figure 17.1). Centers are currently located in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Georgia, Guatemala, Kazakhstan, Kenya, India, South Africa, and Thailand. Several of these grew from existing CDC activities. For example, the laboratory in Guatemala was founded in 1978 as a parasitic diseases research center. Other GDDER centers have built strategic partnerships such as with the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research in Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) and the Naval Medical Research Unit 3 (NAMRU-3) in Cairo, Egypt. The most recent GDDER sites include collaborations in China and South Africa, two additional hot spots in terms of emerging infectious diseases. Sites are chosen in close consultation with the host countries and WHO; new sites are planned but their realization depends, largely, on availability of funding.

Over the period 2006–2011, the GDDER regional centers have responded to more than 900 outbreaks around the world. Provided at the request of the host government, this support is especially important for countries with limited resources or in countries experiencing outbreaks caused by dangerous pathogens such as Ebola virus, Marburg virus, SARS, or Nipah virus. In 2011, the GDD program was responsible for detecting seven pathogens new to their region and three organisms that were new to the world [10].

Much of the value of the GDDER program is realized through building public health capacity in host countries. Since 2006, over 65,000 public health officials had been trained, including 74 graduates of the prestigious Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP).

Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) created the Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System (GEIS) in 1997, soon after a presidential decision directive (PDD-7) mandated that all agencies within the government increase capabilities to detect and respond to global emerging infectious diseases [11]. Through this program, the DoD created a global network based on regional surveillance efforts utilizing DoD overseas medical research laboratories that had been working with host countries for decades on infectious diseases of common interest. These laboratories work side by side with host country scientists in Egypt, Cambodia, Peru, Thailand, Kenya, and numerous other countries. (Figure 17.2). For example, the Naval Medical Research Unit Three (NAMRU-3) based in Cairo, Egypt, was first established to confront typhus during World War II. Over the ensuing decades, the success of NAMRU-3 in this initial control program led to broad infectious diseases research and surveillance initiatives that were mutually beneficial to both countries.

One mission of the GEIS program is to develop, implement, support, and evaluate an integrated global emerging infectious disease (EID) surveillance and response system. Protection of U.S. and allied service members is also a strategic focus. Equally important and well aligned with its primary focus of global public health security is the recognition that adequate health allows for country-level security and, thus, contributes to regional stability—one of the stated strategic goals of the DoD and the U.S. government [12]. By 2012, the GEIS network included 33 partners in 76 countries (Figure 17.2). Key partners continued to be the five DoD overseas research laboratories, each of which has numerous collaborations in their respective regions in Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. The GEIS program has also supported reference laboratories that develop and test diagnostic assays for deployment overseas in addition to conducting disease surveillance in military and nonmilitary associated populations within the United States.

Today, medical research laboratories established by U.S. military are vital to infectious disease surveillance efforts in host countries. Despite political and social strife during the past 60 years, NAMRU-3 remains active in face of infectious disease threats such as avian influenza (influenza A/H5N1). The U.S. Army Medical Research Unit–Kenya (USAMRU–K) has also collaborated in surveillance efforts with national ministries of health and defense for over four decades. The collaborative research partnerships in each of these settings have been responsible for numerous scientific discoveries concerning emerging and tropical infectious diseases, including the isolation of novel pathogens, the first description of artemesinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum, and several reference strain contributions to Northern and Southern hemisphere influenza vaccines (including the seed strain for the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 virus) [11].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree