Surveillance for HIV in the United States

1 HIV Counts, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

2 South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (Retired), Columbia, SC, USA

Introduction: Biology and Natural History of HIV

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that contains a reverse transcriptase enzyme. When HIV enters the human cell, it transcribes the viral RNA into host-recognizable DNA that directs the cell to manufacture more copies of the virus. When persons first become infected with HIV via sex or exposure to blood, they usually undergo a brief illness resembling infectious mononucleosis but then have no remarkable symptoms for approximately 8–10 years until they develop stage 3 HIV infection (AIDS). As the immune system is progressively damaged by HIV infection, the patient becomes more susceptible to certain infections and cancers, many of which were extremely uncommon before the HIV epidemic; these are referred to as “opportunistic illnesses” (OIs). Presence of these OIs or a very low level of CD4 cells define stage 3 (Table 13.1) [1]. Common HIV-related OIs include Pneumocystis pneumonia, candida esophagitis, and Kaposi’s sarcoma. It was the increase in incidence of such OIs in the early 1980s that allowed the initial detection of the HIV epidemic and that was the initial hallmark of AIDS.

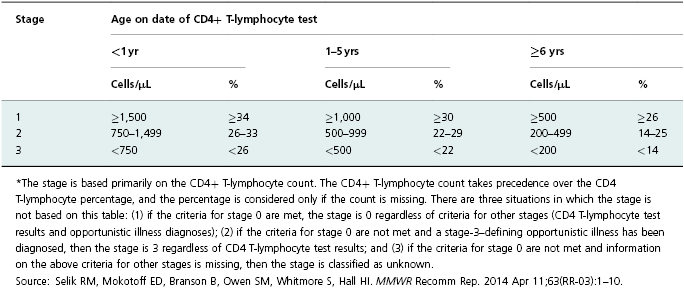

Table 13.1 HIV infection stage* based on age-specific CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes.

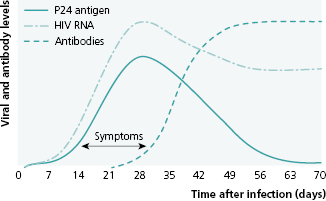

When a person is first infected with HIV, the amount of virus in his blood peaks within 3 weeks and then drops (Figure 13.1). The probability of transmitting HIV to another person is roughly proportional to the concentration of virus in a person’s blood, known as “viral load,” which is an indicator of both the patient’s health status and his potential to infect others. Although it is not yet routinely possible to cure HIV infection (i.e., eliminate the virus from the person’s body), the development of effective and safe antiretroviral drugs has radically changed the natural course of disease. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can slow or stop production of new virus, rendering the person’s viral load undetectable. This can bring the HIV-infected person back to health; but even with an undetectable viral load, the infected individual still has HIV-infected cells and must take antiretroviral treatments (ART) for life. This is very difficult to do consistently; yet it is critical, because the virus is capable of very rapid mutation; and intermittent medication adherence will cause resistance of the patient’s virus to the drugs he is receiving, necessitating a change to other antiretroviral drugs that may be more toxic and expensive.

Source: Das G, Baglioni P, Okosieme O. Easily Missed? Primary HIV Infection. BMJ 2010; 341:c4583. Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

During the time after initial infection when a person displays minimal symptoms (usually years) a person’s HIV status is only detectable by testing. Thus the number of newly identified HIV infections in a population in a year is not a measure of the true incidence of infection, but rather reflects new diagnoses and is related to the intensity and effectiveness of testing in that community. True incidence is currently measured using a special testing algorithm that integrates information on the testing history of all persons diagnosed with HIV in the population [2].

The initial indicator of the course of the epidemic, the AIDS death rate, is no longer useful for that purpose because of prolonged survival of persons in care. Today at least four key characteristics of the epidemic should be monitored: (1) rate of occurrence of new infections and the demographic and behavioral characteristics of those persons, (2) proportion of diagnosed HIV-infected persons in care and taking treatment consistently, (3) proportion with an undetectable viral load, and (4) rate of antiviral drug resistance. Measurement of all these parameters is the responsibility of the HIV surveillance program.

Surveillance Implications of the Unique Epidemiology of HIV

The surveillance systems for all stages of HIV infection, including stage 3 (AIDS), are the most highly developed, complex, labor-intensive, and expensive of all routine infectious disease surveillance systems. This additional complexity and cost is justified by the enormous cost of HIV disease to society and by the numerous opportunities for prevention of the disease and its complications [3].

The epidemiology of HIV impacts surveillance and data use in ways that are nearly unique among human diseases. Its natural course with a long period of asymptomatic infectivity, usually ending in stage 3 and death when untreated, and its modes of transmission often determined by specific behaviors that carry social stigma (e.g., men having sex with men, sharing of intravenous drug equipment) contribute to HIV’s distinctiveness. These special characteristics of the natural course and distribution of HIV disease determine the design and methods of HIV surveillance (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2 How HIV’s epidemiology and its natural course, as well as the use of data, differ from most infectious diseases.

| Disease characteristic/Data Use | Implications for Surveillance |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic infectious latent period 8–10 years. Much transmission occurs during early acute phase. |

|

| Long, natural course without Rx. There is no cure, but expensive Rx prolongs life. |

|

| Clinical disease presentations are diverse and vary by age group. |

|

| Surveillance data are used to allocate substantial prevention and care dollars. |

|

| Transmission is determined by specific personal behaviors (risk factors). |

|

| There is serious stigma in many communities throughout the United States and overseas. |

|

Although some behaviorally based prevention interventions (e.g., individual counseling and testing) are relatively inexpensive and simple to implement, others are expensive and difficult to maintain. Consequently, HIV control programs have added more treatment-based methods in recent years. These consist primarily of routine and, in some populations, repeated and frequent testing for HIV with an emphasis on diagnosing every infected person as quickly as possible, linking them to clinical care, prescribing ART, monitoring for retention in care, and maintaining an undetectable viral load. This approach is referred to as “treatment as prevention.” Another treatment-based strategy is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) which consists of giving ART to uninfected people before they are exposed to HIV [4]. Surveillance data are used to evaluate the success of these strategies, increasing the need to collect ongoing detailed patient care data and broadening the scope of HIV surveillance.

HIV surveillance data are used for many purposes: delivering direct patient services (prevention counseling, linkage to and retention in care, adherence to ART, and assisting patients with notifying their sexual partners), monitoring the scope, geographic distribution and secular trends of HIV infection, monitoring risk behavior to target prevention and planning, evaluating prevention and care programs, and contributing to applied research.

The Impact of Stigma on the Development of HIV Surveillance Systems

In the United States, initial cases of AIDS were described in 1981 among young, white, gay men with very high numbers of sexual partners [5]. The need for public health to conduct surveillance for a disease that was spreading rapidly with high mortality rates and engendering fear among the first-infected populations was urgent. Surveillance was viewed with suspicion among the affected groups, who had already experienced discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation. However, because of the urgency to understand this frightening syndrome, name-based AIDS surveillance was not opposed by AIDS advocacy groups. Public health officials at the state or local health-department level established a traditional surveillance system based on collection of name, address, date of birth, and presumed mode of transmission. Names are collected by state and local health departments for several reasons: (1) they enable state and local public health officials to determine if subsequent case reports are the same or a different person; (2) they facilitate contact with the patient to assist in notifying sex- or needle-sharing partners about their potential exposure to HIV; (3) they allow updating of the case reports with vital status (i.e., death) and, in the current era of ART, with laboratory data that measure immune system status and viral load; and (4) they allow the health department to contact the patient to assist with linkage to and reengagement in care. Contacting partners of persons diagnosed with HIV has increased in importance as we have gained evidence that getting HIV infected persons into care early can decrease their viral load improving their long-term health and decreasing their risk of transmitting HIV [6]. Contacts who are found to be HIV-negative can be provided with risk-reduction counseling. Confidentiality concerns were lessened by removing names of cases from data forwarded to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Instead, in national data, cases were identified only by Soundex code [7] and date of birth.

Surveillance data could describe how and to whom HIV was spreading; but, during the early course of the HIV epidemic, the political context of discrimination against gay men produced opposition to surveillance of persons with HIV who had not progressed to AIDS. This opposition was widespread because persons who had not yet progressed to severe HIV disease had more to lose if their infection status was known because of ongoing stigma associated with a positive status [8]. Nonetheless, by 2006, 21 years after the virus was identified and an antibody test was developed to diagnose it, all 50 states had name-based HIV surveillance systems.

The unique epidemiology and political context of HIV have important implications for the public health response. HIV’s social stigma underscores the need for surveillance programs to maintain the highest standards of data security and confidentiality, and also emphasizes that public health must justify mandatory reporting.

Surveillance Methods for HIV

Case Identification

Surveillance for any disease must begin with a case definition so that a single standard is used to decide who to include as a case. The HIV case definition varies by age group, because the human immune and clinical response to HIV infection and the interpretation of the different tests varies with age (Table 13.1). For example, for the first 12–18 months of life a perinatally infected infant will have circulating antibodies from maternal infection, which mask the presence or absence of an infant immune response [9].

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, case definitions for HIV infection and AIDS have undergone several revisions to respond to changes in methods of diagnosis of HIV infection and the opportunistic illnesses (OIs) that defined AIDS. By 2008, HIV testing was more integrated into medical care, and laboratory tests for HIV became extraordinarily sensitive and specific. These changes continued and are reflected in the 2014 revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection [1]. Unlike case definitions before 2008, which were separate for non-AIDS HIV infection and AIDS, the 2014 version is an HIV definition and classification system presenting AIDS as stage 3—the most severe stage of a continuum of HIV infection based on either a low CD4 count or percentage or one or more stage 3 defining opportunistic illnesses (Table 13.1) [1]. The 2014 definition also includes a stage for early HIV infection (stage 0) recognized by a negative HIV test within 6 months of HIV diagnosis, because current (2014) testing algorithms are more sensitive during early infection than previous tests. This is important for public health purposes because early infection includes the most highly infectious period when intervention might be most effective in preventing further transmission. The HIV case definitions described here are for public health surveillance only and are too rigid to be a basis for making a clinical diagnosis [1].

Data Sources and Case-Finding

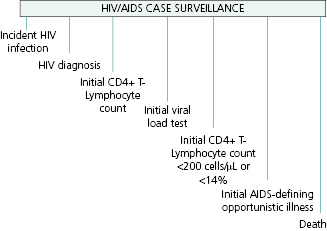

HIV infection may be detected at any point during the progression of the disease, and thus the reportable events range from detection in an asymptomatic person, through occurrence of initial symptoms of disease, low CD4 counts, an OI defining stage 3, or detection only at death (Figure 13.2).

Reporting of HIV by healthcare providers and clinical laboratories is mandated in all jurisdictions in the United States. However, because of underreporting, active surveillance is necessary to ensure complete ascertainment. Active surveillance involves health department staff regularly contacting potential sources of new cases such as hospitals, physicians’ offices, and correctional facilities to obtain case reports. Case reports can be completed by health department staff through review of paper or electronic medical records at provider sites and/or through securely accessing their electronic medical record off site. Public health departments may also help sites to complete case report forms using health department telephone support, or they may simply require the site to complete the case report form and mail it in or submit it electronically. Some health departments encourage sites to complete the HIV case report form online, using electronic disease reporting systems that are used for all notifiable diseases.

Establishing an active surveillance system for HIV involves the following basic activities:

- Identifying reporting sources

- Establishing reporting routines with the laboratories that perform diagnostic tests

- Establishing communication with clinicians who diagnose and care for persons living with HIV and motivating them to report and/or establishing a procedure for reviewing medical records to complete case report forms including ascertainment of risk factors

- Establishing electronic reporting of laboratory tests

- Analyzing the data and distributing statistical reports—both so the data are used and as feedback to reporting sources

When a case report is first received in the surveillance unit from a reporter outside of the health department it must be reviewed by trained staff to ensure that it is complete, meets the case definition, and is not missing required variables such as name, race, sex, or date of birth. CDC will not accept as a valid case one that is missing a required variable: state ID number, last name Soundex code, sex at birth, date of birth, vital status, date of death (if dead), race/ethnicity, date of first positive HIV test result or physician diagnosis of HIV, and (if applicable) date of first condition qualifying the case as stage 3 using the current case definition. Although not required by CDC, mode of transmission (risk) is critically important for the users of surveillance data. When it is missing, follow-up is done to obtain the information.

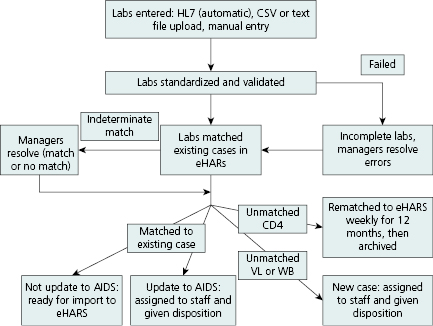

Electronic Laboratory Reporting

Electronic laboratory reporting (ELR) is laboratory data (results) that arrive in an electronic format (e.g., HL- 7, ASCII, spreadsheet). However, once they arrive at the health department results must be standardized, validated, entered, and/or uploaded or transferred into an electronic database that can be matched to the HIV registry. Reported laboratory results that do not match previously reported HIV cases must be distributed to staff for follow-up and reporting. The complex process includes monitoring data quality for errors and missing values, parsing, and uploading the data automatically into the database. Figure 13.3 illustrates the flow of ELR for HIV surveillance in Michigan.

Reporting of individual HIV-related laboratory results (e.g., positive confirmatory HIV antibody tests, viral detection results, and CD4 counts) directly by laboratories to surveillance programs can support key surveillance objectives and facilitate timely case ascertainment [10]. Receipt of laboratory results that indicate a new case leads to (1) medical chart abstractions done either electronically at the health department, (2) visiting the site, or (3) triggering a reminder to a healthcare provider to report. Laboratory reporting has become the most frequent mechanism for both learning of new cases and staging a case of HIV, for example, as stage 3 if a CD4 count <200 cells/μL or <14% in a person age 6 or older is reported (Table 13.1). Laboratory results are also used to monitor access to care for persons newly diagnosed, estimate the level of unmet need for medical care, and assess viral load.

Prior to the advent of HAART in the mid-1990s, surveillance consisted primarily of collecting initial HIV diagnosis, followed by monitoring of progression to AIDS and death. The current need to monitor adherence to treatment and care has led to surveillance to collect results of all CD4 count and viral load tests conducted on HIV-infected persons. Treatment guidelines recommend such testing quarterly [11], leading to dozens of laboratory tests being reported for each HIV-infected person in care; hence, the need to receive laboratory results electronically and efficiently has increased. While all states require reporting at some level of CD4 count or viral load results (e.g., <200 μL or detectable viral loads), not all states require reporting of all levels and not all send these data to the CDC for inclusion in national reports. As of January 2013, 39 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia required reporting of all levels of CD4 and viral load test results; 19 of these areas had reported at least 95% of the results to CDC [12].

Surveillance Activities Specific to HIV

The activities listed in the previous section, including establishing a case definition, conducting active surveillance, and relying upon laboratory reporting, can apply to surveillance for other infectious diseases. There are other approaches used specifically in surveillance for HIV: linkage with other disease registries, evaluation requirements and published performance standards established by the funding agency (CDC) and local jurisdictions, and the requirement to analyze and distribute the data.

Data Sources and Data Flow

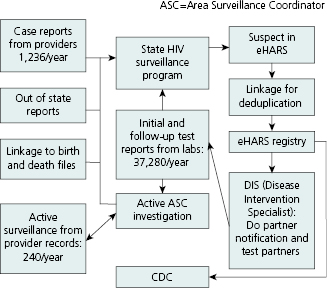

Although data flow varies somewhat from one jurisdiction to another, the basic reporting sources and processes are the same. Figure 13.4 shows the main data sources and routing for the South Carolina HIV Surveillance Program in 2010. To maximize case detection, programs seek patient-level data on HIV test results from a variety of sources. Data are received from medical provider case reports, laboratories doing diagnostic or other clinical tests regarding HIV, linkages to files of death and birth certificates, other state health departments, and active surveillance by area surveillance coordinators (ASCs). Prompted by lab reports of positive HIV tests, ASCs obtain completed case report forms from provider medical records and collect other key information such as patient race/ethnicity and risk-factor behavior.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree