Surveillance of Viral Hepatitis Infections

1 Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Jamaica Plain, MA, USA

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

Introduction

In the United States, public health surveillance activities for viral hepatitis vary among jurisdictions. At the national level, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide recommendations, guidance, and analysis. In addition to participating in the national surveillance network (National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System [NNDSS]), state and local health departments are responsible for the development and implementation of their own surveillance systems and adoption of national guidelines. Local policies and resources determine the extent to which surveillance and epidemiological strategies can be implemented and achieved. State and local health departments rely on the active participation of clinical providers and laboratories for key laboratory, clinical, and epidemiological information. Other data sources may also be utilized to further the understanding of the infections, diseases, and disease patterns.

Use of these data supports a range of public health activities. These may include disease prevention and control, program and policy development, evaluation, and resource allocation. However, because surveillance methodologies across the diseases have not been uniformly funded, established, or assessed, viral hepatitis surveillance systems are still evolving.

Clinical Background of Viral Hepatitis

Hepatitis—inflammation of the liver—can have many causes, both infectious and noninfectious. The hepatitis viruses (A through E) are unrelated viruses that primarily cause communicable hepatitis. Prior to the elucidation of specific viral etiologies for hepatitis in the 1960s and 1970s, hepatitis was classified as short-incubation “infectious” hepatitis and long-incubation “serum” hepatitis. Infectious hepatitis was characterized by acute infection, often foodborne with a fecal–oral route of transmission and occurrences in outbreaks or clusters. Serum hepatitis was most commonly recognized as a consequence of blood transfusion and injection drug use, as well as a complication of contaminated medical injections. Hepatitis A and E are etiologic agents causing hepatitis most consistent with what was called infectious hepatitis; and hepatitis B and C are long-incubation, bloodborne, and (particularly hepatitis B) sexually transmitted. Hepatitis D virus is a “defective” virus that depends completely on hepatitis B coinfection to replicate and generally causes more severe disease as a consequence of coinfection.

Blumberg reported Australia antigen in the serum of leukemia patients in 1965 [1] and recognized it as a marker for hepatitis B in 1968 [2]—first designated “hepatitis-associated antigen” (HAA) and then “hepatitis B surface antigen” (HBsAg). Hepatitis A virus (HAV) was identified in stool in 1973 [3], and a serologic test for IgM antibody became available after 1977 [4]. Once hepatitis A and B were defined etiologically, there remained hepatitis cases that were “non-A, non-B,” in particular long-incubation hepatitis, primarily related to transfusion of blood products, as well as some epidemic infectious hepatitis that was not hepatitis A. After years of seeking the etiologic agent, hepatitis C virus (HCV) was identified, and a serologic test for anti-hepatitis C antibody was reported in 1989 [5,6]. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) was originally thought to be a “delta antigen” of HBV [7]; but, subsequently, it was demonstrated to be a distinct agent that was completely dependent on hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection [8]. Hepatitis E virus (HEV), as a cause of epidemic hepatitis with a fecal–oral transmission route, was first identified in 1983 [9] and was associated retrospectively with earlier outbreaks.

Acute hepatitis of any cause has similar, usually indistinguishable, signs and symptoms. Acute illness is associated with fever, fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, followed by signs of liver dysfunction, including jaundice, light to clay-colored stool, dark urine, and easy bruising. The jaundice, dark urine, and abnormal stool are because of the diminished capacity of the inflamed liver to handle the metabolism of bilirubin, which is a breakdown product of hemoglobin released as red blood cells are normally replaced. In severe hepatitis that is associated with fulminant liver disease, the liver’s capacity to produce clotting factors and to clear potential toxic metabolic products is severely impaired, with resultant bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy. Characteristic laboratory findings of liver damage of any cause are elevations of bilirubin and liver enzymes, such as alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) [10]. Acute hepatitis may be associated with ALT (or AST) levels from 5 to greater than 100 times the upper limit of normal. Other tests used to evaluate liver function are tests for alkaline phosphatase (a measure of damage and dysfunction), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT, a measure of liver cell dysfunction), albumin (a protein product of reduced liver function), and measures of clotting. None of these tests is entirely specific to liver disease.

Chronic hepatitis—persistent and ongoing inflammation that can result from chronic infection—usually has minimal to no signs or symptoms; but it might result in fatigue and other nonspecific symptoms. There are a number of methods of assessing the extent of liver damage, including liver biopsy and other less-invasive procedures and tests. Ongoing chronic hepatitis can result in scarring (fibrosis) of the liver that can lead to progressive liver disease and severe damage characterized by cirrhosis (scarring with nodular distortion of the liver architecture) [11]. Cirrhosis leads to severe dysfunction in the metabolic clearing and synthetic functions of the liver, as well as restriction of the blood flow from the gastrointestinal tract through the portal vein to the liver. This portal hypertension leads to risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and shunting of blood to the systemic circulation, further reducing the clearance of potentially toxic substances by the liver tissue that remains. Portal hypertension and low serum albumin contribute to the collection of fluid in the abdominal cavity constituting ascites. A possible complication of chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the liver from any cause is liver cancer.

HAV and HEV infections cause acute disease worldwide, which is self-limited and associated with a low case fatality rate (<1% for A and ∼2–4% for E); but hepatitis E has approximately a 10-fold higher mortality rate in pregnant women. Many cases of both infections are subclinical (without recognized illness). The presentation of symptoms is age related. That is, among children <6 years of age, illness is mostly asymptomatic; whereas, among adults, illness is mostly symptomatic (Table 11.1). An effective vaccine to prevent hepatitis A has been available for more than 15 years, and incidence rates of hepatitis A are dropping wherever it is used in routine childhood immunization programs. Hepatitis E has 4 genotypes with different epidemiologic characteristics, but similar disease [12]. While primarily transmitted by the fecal–oral route, infection has also been described as resulting from exposure to products from infected animals.

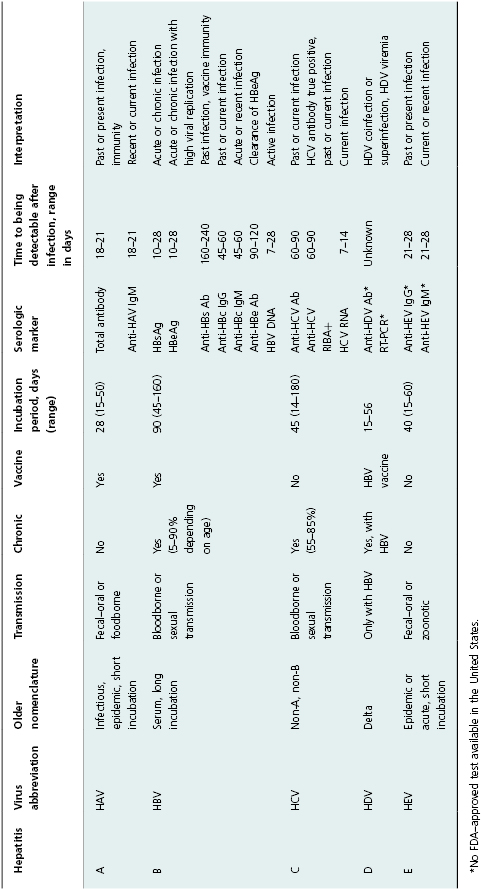

Table 11.1 Summary of viral hepatitis A–E, inclusive of serologic tests in clinical use.

Hepatitis B and C viruses cause acute hepatitis as well as chronic hepatitis. The acute component is often not recognized as an episode of acute hepatitis, and the chronic infection may have little or no symptoms for many years. With hepatitis B, clearance of infection is age related, as is presentation with symptoms. Over 90% of infants exposed to HBV develop chronic infection, while <1% have symptoms; 5–10% of adults develop chronic infection, but 50% or more have symptoms associated with acute infection. Among those who acquire hepatitis C, 15–45% clear the infection; the remainder have lifelong infection unless treated specifically for hepatitis C. (Currently available treatment can result in sustained viral response in 70–90% of those infected). HDV infection can occur as a coinfection with HBV, in which case the course is similar to HBV infection alone; HDV can also superinfect someone with chronic HBV infection, leading to a tendency for more progressive liver disease [13].

A number of laboratory tests (antibody, antigen, and nucleic acid) have provided markers of viral hepatitis that can be used to diagnose infection, monitor patients, and categorize cases for surveillance purposes. These laboratory tests and the basic characteristics and epidemiology of the forms of viral hepatitis are summarized in Table 11.1. Currently, acute hepatitis A, acute hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis B, HBV perinatal infection, acute hepatitis C, and past or present hepatitis C are nationally notifiable for public health surveillance purposes in the United States.

Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis

Much of what is known about the epidemiology of viral hepatitis was derived from observations of outbreaks prior to the identification of specific etiologic agents. The development of diagnostic laboratory tests enabled the investigation of cases that could be identified clinically or through serologic surveillance. Public health and military investigations helped define “infectious,” “epidemic,” and “serum” hepatitides as clinical and epidemiologic entities [14,15]. Specific diagnosis of hepatitis A, hepatitis B (and D), and later hepatitis C allowed for inquiry into risk factors and behaviors associated with infection. Current studies are further defining the epidemiology of hepatitis E.

Investigation of the incidence of viral hepatitis in the United States has been pursued in the past via sentinel surveillance studies of acute hepatitis that CDC funded in six counties around the United States [16]. The Sentinel Counties Study of Viral Hepatitis was a population-based study conducted in seven U.S. counties: Contra Costa, California; San Francisco, California; Multnomah, Oregon; Jefferson (Birmingham), Alabama; Denver (Denver), Colorado; Pinellas (St. Petersburg), Florida; and Pierce (Tacoma), Washington from 1996 to 2006 [17]. All patients in those regions who were identified with acute viral hepatitis were reported to the respective county health department. Case definitions used for this study required both clinical and serologic criteria. Serum specimens from patients with acute disease were collected within 6 weeks of onset of illness and tested for serologic markers of acute infection with known hepatitis viruses. To obtain epidemiologic information, each patient was interviewed by a trained study nurse, who used a standard questionnaire. The questionnaire collected select demographic, clinical, and risk-factor information for the 2–6 weeks preceding onset of illness. The data collected from this study have been instrumental in understanding the epidemiology of viral hepatitis infections in the United States. However, the understanding of the extent of the epidemics determined by this study and other ongoing disease surveillance is limited because data are only received on individuals accessing care. Asymptomatic acute infection and poor or unavailable measurements for high risk populations, including injection drug users and immigrants from endemic countries, have resulted in questionable estimates of the prevalence and incidence of hepatitis B and C. Further, a lack of understanding of the different types of viral hepatitis by many medical providers [18] has led to many undiagnosed individuals living with chronic infection, who are not captured in disease surveillance systems.

Serologic surveys of various population groups have helped to define demographic and risk correlates of infection. Clinical and population research and observation has produced a risk profile for all of the types of viral hepatitis. A summary of the major risk factors, correlates, and screening recommendations are presented in Table 11.2. These data inform understanding of transmission parameters and what is needed for prevention of transmission. A particularly valuable source of information on the correlates of infection with hepatitis viruses is the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [19]. This periodic survey that is performed by the CDC samples the general population. Medical and behavioral histories are collected, as well as clinical specimens that may be tested for markers of infection. However, institutionalized populations, including those that are incarcerated or live in college and university housing are not included in the sampling; and this likely contributes to underestimates of HCV infection [20].

Table 11.2 Summary of viral hepatitis A–E risk history and screening recommendations

Source: Except where noted, adapted from CDC, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, September 19, 2008; 57 (RR-8): 8–10 and October 16, 1998; 47 (RR-19): 20–26.

| Hepatitis type | Relevant risk behaviors/history | Screening recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| A |

|

|

| B |

|

|

| C |

|

|

| D |

|

|

| E |

|

|

Purpose of Viral Hepatitis Surveillance

The purpose of conducting surveillance is to inform public health action. Acute hepatitis infections are routinely investigated to determine a source of infection (e.g., food, healthcare facility, household contact), to identify contacts, and to limit further transmission [21,22]. Surveillance data can serve as infrastructure to conduct special studies that clarify the role of a specific mode of transmission. For example, concerns about outbreaks of hepatitis B and C among residents of assisted living facilities prompted a surveillance-based case control study among persons >55 years of age to assess risk factors for viral hepatitis [23].

Primarily because of resource constraints, the potential utility of chronic hepatitis surveillance registries for case management has not been established [24]. However, there are a number of reasons to perform surveillance of these infections. First, the routine screening, reporting, and subsequent case management of pregnant women for HBV infection can help insure prevention of chronic infection in the newborn [25]. Second, because acute HBV and HCV infections are frequently not clinically apparent and are underreported, reports of past or present infection may be the only way to identify likely acute infections. Third, surveillance of chronic infection is an important component in the determination of resource allocation and evaluation. Identification of populations at highest risk can guide development of appropriate services. These may include prevention services (e.g., provision of sterile needles and syringes), testing programs, and linkage to care. Finally, linkage to clinical care may be useful in ensuring that individuals with chronic viral hepatitis receive appropriate medical care, including antiviral treatment. It has also been suggested that identification and follow-up of all individuals with chronic HBV or HCV infection can be used to detect other at-risk or infected individuals (e.g., family and household contacts, drug sharing partners) and to ensure appropriate preventive screening or care [18]. Box 11.1 summarizes key reasons to conduct acute and chronic viral hepatitis surveillance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree