Neutropenia is a common reason for hematology consultations in the inpatient and outpatient settings and is defined as an absolute neutrophil count less than 1500 cells/μL. Neutropenia varies in severity, with more profound neutropenia being associated with higher rates of infections and infection-related deaths. The causes for neutropenia are diverse and include congenital and acquired conditions (ie, autoimmune, drugs, infection, and malignancy). This article outlines the most common causes of neutropenia and discusses differential diagnoses, treatment modalities, and the mechanisms by which neutropenia occurs.

Neutrophil overview

Neutrophils (also called granulocytes) are produced exclusively in the bone marrow during normal conditions. Approximately 10 12 neutrophils are produced per day in the bone marrow and then stored in the marrow until prompted for release by chemokines, cytokines, microbial products, or other mediators of inflammation. Once released into the bloodstream the average half-life of neutrophils is 6 to 8 hours. Circulating neutrophils, the ones reported in a standard complete blood count (CBC), account for only 2% to 3% of all neutrophils. Clearance occurs in the liver, spleen, or bone marrow and occurs through macrophage phagocytosis of aged or apoptotic neutrophils. The local production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines leads to neutrophil attachment to the vascular endothelium and the subsequent transmigration of neutrophils into tissue. The migration of neutrophils into tissue is a key component of the innate immune system, as evident by the increased risk of infections seen in the setting of neutropenia.

Neutropenia

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 1500 cells/μL; it may be mild (ANC 1000–1500 cells/μL), moderate (500–1000 cells/μL), or severe (<500 cells/μL) ( Table 1 ). In general, infection risk increases with ANC less than 1000 cells/μL; however, the risk for infections varies depending on the cause of neutropenia. For example, patients with neutropenia and acute leukemia seem to have a high risk for overwhelming infection in the setting of neutropenia, particularly in cases with ANC less than 500 cells/μL. Therefore, the context in which neutropenia occurs must be considered because some causes of neutropenia, namely ethnic neutropenia and chronic idiopathic neutropenia (CIN), have few overall infection risks.

| ANC | Risk of Infection | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild neutropenia | ANC <1500 but >1000 | Mild |

| Moderate neutropenia | ANC <1000 but >500 | Moderate |

| Severe neutropenia | ANC <500 but >200 | Severe |

| Agranulocytosis | ANC <200 | Severe |

Diagnostic workup

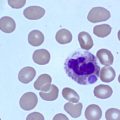

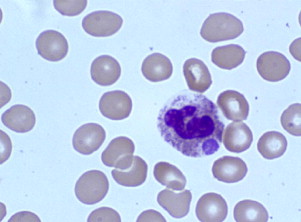

Initial workup consists of a CBC, with a differential count to evaluate the severity of the neutropenia. A full history is also essential to determine race, ethnicity, new medications (including over-the-counter and complementary medications), and potential infectious exposures. Review of systems should focus on fevers, chills, night sweats, weight loss, excess bleeding or bruising, or recurrent infections. A comprehensive physical examination should be performed, with a focus on an examination for signs of infection, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. After this examination, a detailed review of the peripheral smear should follow, to look for neutrophil abnormalities such as Döhle bodies (infection), immature neutrophil precursors (infection, myelodysplasia, myelopthisis), hypoplastic changes in the neutrophils (myelodysplasia), hyperlobulation (nutritional deficiencies), and white cell inclusions (eg, anaplasmosis ( Fig. 1 ), bartonellosis). Review of red cell morphology on peripheral smear may also offer clues to the cause of neutropenia because dacrocytes (teardrop cells) and nucleated red cells (myelodysplasia, fibrosis, myelopthisis) in addition to red cell inclusions (eg, babesiosis, malaria) may all be seen in disease states associated with neutropenia.

Additional routine blood work should include:

- •

Reticulocyte count

- •

Lactate dehydrogenase

- •

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- •

Rheumatoid factor/anticyclic citrullinated protein antibody

- •

Antinuclear antibodies

- •

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- •

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test with confirmation by Western blot

- •

Vitamin B 12 levels

- •

Folate levels.

In cases in which diarrhea is present, stool samples should be checked for the presence of fecal leukocytes and cultured for Shigella and Salmonella . If tick-borne illnesses are part of the differential diagnosis, then an ELISA for Borrelia burgdorferi , the causative agent of Lyme disease, should be ordered and, if positive, the result should be confirmed by Western blot. If babesiosis is suspected, Babesia immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests should be ordered. Anaplasma infection should be evaluated, if needed, by IFA, ELISA, or PCR tests. The granulocyte agglutination test or granulocyte immunofluorescence test for antigranulocyte antibodies to evaluate potential autoimmune neutropenic syndromes may be considered. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be reserved for those cases in which there is a high suspicion for malignancy, either hematologic or metastatic solid tumor.

Neutropenia

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 1500 cells/μL; it may be mild (ANC 1000–1500 cells/μL), moderate (500–1000 cells/μL), or severe (<500 cells/μL) ( Table 1 ). In general, infection risk increases with ANC less than 1000 cells/μL; however, the risk for infections varies depending on the cause of neutropenia. For example, patients with neutropenia and acute leukemia seem to have a high risk for overwhelming infection in the setting of neutropenia, particularly in cases with ANC less than 500 cells/μL. Therefore, the context in which neutropenia occurs must be considered because some causes of neutropenia, namely ethnic neutropenia and chronic idiopathic neutropenia (CIN), have few overall infection risks.

| ANC | Risk of Infection | |

|---|---|---|

| Mild neutropenia | ANC <1500 but >1000 | Mild |

| Moderate neutropenia | ANC <1000 but >500 | Moderate |

| Severe neutropenia | ANC <500 but >200 | Severe |

| Agranulocytosis | ANC <200 | Severe |

Diagnostic workup

Initial workup consists of a CBC, with a differential count to evaluate the severity of the neutropenia. A full history is also essential to determine race, ethnicity, new medications (including over-the-counter and complementary medications), and potential infectious exposures. Review of systems should focus on fevers, chills, night sweats, weight loss, excess bleeding or bruising, or recurrent infections. A comprehensive physical examination should be performed, with a focus on an examination for signs of infection, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. After this examination, a detailed review of the peripheral smear should follow, to look for neutrophil abnormalities such as Döhle bodies (infection), immature neutrophil precursors (infection, myelodysplasia, myelopthisis), hypoplastic changes in the neutrophils (myelodysplasia), hyperlobulation (nutritional deficiencies), and white cell inclusions (eg, anaplasmosis ( Fig. 1 ), bartonellosis). Review of red cell morphology on peripheral smear may also offer clues to the cause of neutropenia because dacrocytes (teardrop cells) and nucleated red cells (myelodysplasia, fibrosis, myelopthisis) in addition to red cell inclusions (eg, babesiosis, malaria) may all be seen in disease states associated with neutropenia.

Additional routine blood work should include:

- •

Reticulocyte count

- •

Lactate dehydrogenase

- •

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- •

Rheumatoid factor/anticyclic citrullinated protein antibody

- •

Antinuclear antibodies

- •

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- •

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test with confirmation by Western blot

- •

Vitamin B 12 levels

- •

Folate levels.

In cases in which diarrhea is present, stool samples should be checked for the presence of fecal leukocytes and cultured for Shigella and Salmonella . If tick-borne illnesses are part of the differential diagnosis, then an ELISA for Borrelia burgdorferi , the causative agent of Lyme disease, should be ordered and, if positive, the result should be confirmed by Western blot. If babesiosis is suspected, Babesia immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests should be ordered. Anaplasma infection should be evaluated, if needed, by IFA, ELISA, or PCR tests. The granulocyte agglutination test or granulocyte immunofluorescence test for antigranulocyte antibodies to evaluate potential autoimmune neutropenic syndromes may be considered. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be reserved for those cases in which there is a high suspicion for malignancy, either hematologic or metastatic solid tumor.

Causes

The most common causes of neutropenia are shown in Boxes 1–3 .

- 1.

Ethnic variations

- 2.

Immune-related

- a.

Primary immune neutropenia

- b.

Secondary immune neutropenia

- i.

Felty syndrome (FS)

- ii.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- iii.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- i.

- a.

- 3.

Infectious

- a.

Sepsis

- b.

Parasitic

- c.

Viral

- d.

Bacterial

- a.

- 4.

Malignancy

- a.

Acute leukemia

- b.

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

- c.

Myelophthisis

- d.

Large granulocytic lymphocytic leukemia

- a.

- 5.

Medication

- a.

Antibiotics

- b.

Cardiac

- c.

Anticonvulsants

- d.

Psychiatric

- e.

Antiinflammatory

- f.

Hypoglycemics

- g.

Antineoplastic agents

- a.

- 6.

Mechanical

- a.

Splenomegaly

- a.

- 7.

Nutritional deficiencies

- a.

Vitamin B 12 (cobalamin)

- b.

Folic acid

- c.

Copper

- a.

- 8.

Other

- a.

Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism

- a.

- 1.

Severe congenital neutropenia (SCN)

- 2.

Cyclic neutropenia

- 3.

WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome

- 4.

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome

- 5.

Barth syndrome

- 6.

Pearson syndrome

- 7.

Glycogen storage disease type 1B

- 8.

Cartilage-hair hypoplasia

- 9.

Dyskeratosis congenita

- 1.

Sepsis

- 2.

Parasitic

- a.

Malaria

- b.

Leishmaniasis (kala-azar)

- c.

Babesiosis

- a.

- 3.

Viral

- a.

HIV

- b.

Human herpesviruses

- i.

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2

- ii.

Varicella zoster virus

- iii.

Epstein-Barr virus

- iv.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- v.

Roseolovirus (sixth disease)

- i.

- c.

Parvovirus B19 (fifth disease)

- d.

Hepatitis A, B, and C virus

- e.

Measles

- f.

Rubella

- a.

- 4.

Bacterial

- a.

Shigella

- b.

Salmonella (typhoid fever)

- c.

Zoonotic diseases (tularemia, brucellosis)

- d.

Anaplasmosis

- e.

Lyme disease

- a.

- 5.

Mycobacterial

- a.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- b.

M avium

- a.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree