Fig. 46.1

Characteristic venous malformations on the sole of the foot of a blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) patient. This skin manifestation on the sole of the foot is pathognomonic for BRBNS

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually exhibit GI bleeding at an early age that continues throughout their life. Massive sudden hemorrhage rarely occurs. Patients typically present with iron-deficiency anemia with the presence of blood in stool. They require lifelong iron replacement and repeated blood transfusions [3].

Occasionally patients also present with a large primary lesion. The primary lesion consists of a large venous malformation (Fig. 46.2).

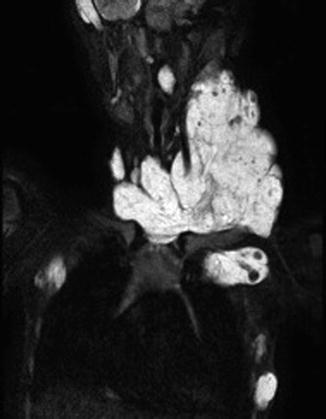

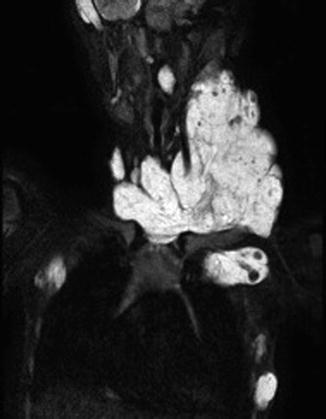

Fig. 46.2

BRBNS patient with a large venous malformation in the neck as the primary lesion. On MRI the muscle infiltrative VM is evident with multiple intralesional thrombophlebitis

Patients with massive presence of VM at any location are associated with the risk of Localized intravascular coagulopathy (LIC). These patients are at risk of local pain due to thrombosis in the venous malformations and the formation of phlebolithes.

LIC leads to a consumption coagulopathy with consumption of fibrinogen, platelets, and thrombocytes due to ongoing clotting within the malformations.

Patients with elevated D-dimer levels associated with low fibrinogen levels (severe LIC) have a high risk of hemorrhage, and if GI lesions are present, bleedings from them increase [4].

Investigation

Patients with BRBNS do not differ from other patients presenting with iron-deficiency anemia with the presence of blood in the stool.

The investigation starts with an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and coloscopy.

If the clinical picture is mild, a wireless capsule endoscopy can be performed in order to investigate the small intestines.

Clinical presentation with typical skin lesions for BRBNS (Fig. 46.1) and iron-deficiency anemia with the presence of blood in stool require an investigation with diagnostic laparoscopy. The diagnostic laparoscopy will confirm the presence of venous lesions prior to converting to open surgery and also will rule out other more common bleeding sources in this age group such as Meckel’s diverticulum.

The investigation of the small intestines is carried out with a push-enteroscopy where small incisions are made in the intestines and a sterile laparoscopic camera or a flexible gastro scope is inserted in the bowel and pushed through.

All patients are analyzed for coagulopathy. When there is evidence of LIC or severe LIC it is likely to be correlated with high presence of VM in the GI tract and often also a large primary lesion.

Treatment

The management of patients with BRBNS is built on several factors. Pharmacological treatment and aggressive surgical removals of lesions in the GI tract with multiple local resections will keep the patient free from bleeding. The management consists of extensive intestinal surgery with local excisions up to several hundred in one patient [3]. However the management also requires surgery or intervention to reduce the primary lesion.

If the lesions are within the reach of endoscopes, the treatment can be performed with endoscopic argon diathermia [11] (Fig. 46.3b, c).

Fig. 46.3

(a) Intestines with venous malformation associated with BRBNS. (b) Endoscopic view of venous malformation associated with BRBNS. (c) Endoscopic APC (Argon Plasma Coagulation) of venous malformation associated with BRBNS

Patients with high D-dimers as a sign of severe LIC and a presence of a large primary venous malformation must be treated with the aim to lower the overall presence of venous malformation. In these cases, the surgery and/or intervention is not limited to the GI tract but also to the primary venous malformation, in order to have less intralesional coagulation that causes LIC.

However BRBNS patients with severe LIC and ongoing bleedings that cannot be managed surgically or interventional are candidates for anticoagulation with low molecular heparin [4].

In addition to surgical and interventional treatment in severe cases of BRBNS with bleeding, there are some resent reports of the use of the immunosuppressant drug sirolimus also known as rapamycin that may be useful [2].

Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome, GI Tract Aspects

Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome is a triad that consists of the following: (a) cutaneous port-wine capillary malformation, (b) mixed venous and lymphatic anomalies, and (c) hypertrophy of a limb.

The lower limbs are more commonly affected often with pelvic extension. This syndrome is present at birth, but progression of venous anomalies and limb hypertrophy is observed during growth. GI involvement in Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome due to the pelvic extension of both venous and lymphatic malformation usually takes place in the colorectal area. The lymphatic extension may expand in the pelvis and press on anatomical structures such as the bladder and the rectum. Treatments of these lesions are planned according to the symptoms that they cause. The venous malformation in the GI tract is often present as dilated submucosal veins and occasionally causes GI bleedings (Figs. 46.4, 46.5, and 46.6).

Fig. 46.4

MRI shows pelvic expansion of lymphatic and venous malformation in a patient with KTS

Fig. 46.5

Endoscopic view, dilated submucosal veins in patient with KTS

Fig. 46.6

Endoscopic sclerotherapy with microfoam in the rectum on a KTS patient with bleeding from dilated hypertensive veins

Patients with KTS in accordance to other patients with massive presence of VM such as patients with BRBNS also often have high D-dimers associated with low fibrinogen as an evidence of LIC.

High venous congestion in the affected limb and high D-dimers as an evidence of severe LIC is correlated to high risk of bleeding from the vascular lesions including the VMs present in the GI tract.

Treatment Aspects

KTS patients with venous malformations involving the GI tract can be treated locally with endoscopic sclerotherapy to the dilated submucosal veins. This will stop ongoing bleedings (Fig. 46.6). Resection of rectum is rarely indicated; thus, if there is severe bleeding with no possibility of medical treatment or surgical stepwise intervention, resection may be mandated [5].

The presence of large ecstatic veins surrounding the rectum that are in connection with the inferior mesenteric vein is a significant risk factor of pulmonary embolism (PE). In such case, interventional coiling or surgery is mandated to prevent PE.

The main treatment strategy however in the management of KTS patients with GI tract involvement is to lower the tissue congestion in the patients affected limb in order to lower the risk of consumption coagulopathy and thus to lower the venous pressure. Both these aspects will lower the risk of bleedings and thromboembolism.

In KTS patients with high risk of PE and evidence of consumption coagulopathy with severe LIC should be considered antithrombotic therapy with low molecular heparin [4].

Lymphatic Malformations in the Viscera

Lymphatic malformations (LM) are defined as structural defects that occur because of defective lymphangiogenesis [6]. They may expand in the tissue with large cystic components (macrocystic LM) or infiltrative with small cysts (microcystic LM).

Histologically, LMs are benign lesions, but because of their localization and their size they can cause serious complications, i.e., compromise to vital anatomical structures. The incidence of abdominal lymphatic malformations is unknown; however, 75 % of all LMs occur in the head and neck region and the visceral LMs account for from 3 to 9 % of all pediatric LMs. LM recurrently get infected or inflamed causing peritonitis, pain, and septicemia. A sudden swelling within the malformation may also cause compromise to adjacent vital anatomical structures and functions [12].

Clinical Presentation

The majority of patients with LM in the viscera present in childhood. Abdominal cystic LM arise from the mesentery (59–68 %) (Fig. 46.7), omentum (20–27 %) (Fig. 46.8), and retroperitoneum (12–14 %) (Fig. 46.9) [13, 14].

Fig. 46.7

A six-year-old girl, 1 week vomiting, and abdominal distention. Last days increasing abdominal pain and fever. (a) MRI showing mainly large cysts intra abdominally. (b) Preoperative view showing abdominal distention. (c) Operative view showing visceral LM involving the mesentery of a limited part of the small intestine. (d) End-to-end anastomoses after resection of 25 cm affected bowel with lymphatic malformation in the mesentery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree