Urticaria, Angioedema, and Hereditary Angioedema

Carol A. Saltoun

The earliest texts called urticaria and angioedema “a vexing problem” (1). Little has changed since that assessment. Today’s clinician is still faced with a common syndrome that affects 20% of the population at some time in their lives (2), but there is no cohesive understanding of the many clinical mechanisms, presentations, or clinical management of the urticarias. For the clinician, this requires a broad knowledge of the many clinical forms of urticaria and an even more extensive familiarity with the creative ways that medications and treatment can be applied. Modern concepts of allergen-induced cellular inflammation, late-phase cutaneous responses, adhesion molecules, cytokines, inflammatory autocoids, and autoantibodies are leading to a better understanding of pathogenesis and treatment. Meanwhile, clinicians should formulate a rational approach to the care of patients with these conditions.

Urticarial lesions can have diverse appearances. Generally they consist of raised, erythematous skin lesions that are markedly pruritic, tend to be evanescent in any one location, are usually worsened by scratching, and always blanch with pressure. Individual lesions typically resolve within 24 hours and leave no residual skin changes. This description does not cover all forms of urticaria, but it includes the features necessary for diagnosis in most clinical situations. Angioedema is associated with urticaria in 40% of patients, but the two may occur independently (3). Angioedema is similar to urticaria, except that it occurs in deeper tissues and is often asymmetric. Because there are fewer mast cells and sensory nerve endings in these deeper tissues, pruritus is less common with angioedema, which more typically involves a tingling or burning sensation. Although urticaria may occur on any area of the body, angioedema most often affects the perioral region, periorbital regions, tongue, genitalia, and extremities. In this review, angioedema and urticaria are discussed jointly except where specified.

The incidence of acute urticaria is not known. Although it is said to afflict 10% to 20% of the population at some time during life, it is most common in young adults (1). Chronic urticaria occurs more frequently in middle-aged persons, especially women. In a family practice office, its prevalence has been reported to be 30% (4). If patients have chronic urticaria for more than 6 months, 40% will continue to have recurrent wheals 10 years later (5). The presence of angioedema, severity of symptoms, and evidence of autoimmune mechanism have been shown to prognosticate longer duration of disease; however, race, education, smoking, comorbidity and atopy did not influence duration (3,6,7). It is possible that the true prevalence of urticaria is higher than reported owing to many acute, self-limited episodes that do not come to medical attention.

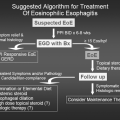

Acute urticaria is arbitrarily defined as persisting for less than 6 weeks, whereas chronic urticaria refers to episodes lasting more than 6 weeks. When considering chronic urticaria, an etiologic agent or precipitating cause such as a physical urticaria is established in up to 30% of patients who are thoroughly evaluated (8). However, most chronic urticaria is idiopathic. Success rates of determining an inciting agent are higher in acute forms. Because of the sometimes extreme discomfort and cosmetic problems associated with chronic urticaria, a thorough evaluation to search for etiologic factors is recommended. This evaluation should rely primarily on the history and physical examination as well as response to therapy; limited laboratory evaluation may be indicated based on history and physical exam findings (Fig. 31.2). In a study of 238 consecutive new patients with chronic urticaria and/or angioedema, subjects were initially worked up with a questionnaire and limited laboratory tests. Subsequently they were evaluated with a rigorous screening program including biopsy, extensive blood tests, radiography, provocation tests, and elimination diets. After the rigorous workup,

only one patient was found to have a cause for their urticaria that would not have been found with the initial workup alone (9).

only one patient was found to have a cause for their urticaria that would not have been found with the initial workup alone (9).

Pathogenesis

There is no unifying concept to account for all forms of urticaria; however, because erythema, edema, and localized pruritus are mimicked by intracutaneous injection of histamine, its release is thought to be the underlying mediator. The hypothesis that histamine is the central mediator of urticaria is bolstered by (a) the cutaneous response to injected histamine; (b) the frequent clinical response of various forms of urticaria to therapeutic antihistamines; (c) the documented elevation of plasma histamine or local histamine release from “urticating” tissue in some forms of the condition; and (d) the apparent degranulation of skin mast cells. Tissue resident mast cells or circulating and/or tissue-recruited basophils continue to be the presumed source of the released histamine. Understanding the mechanisms responsible for the release of histamine in the various forms of urticaria continues to be the focus of current research.

Several potential mechanisms for mast cell activation in the skin are summarized in Table 31.1 and include (a) immunoglobulin E (IgE) immediate hypersensitivity such as occurs with penicillin or foods, (b) activation of the classical or alternative complement cascades such as occurs in immune complex disease like serum sickness or collagen vascular disease, (c) direct mast cell membrane activation such as occurs with injection of morphine or radio contrast media, and (d) generation of thrombin from the extrinsic coagulation pathway with mast cell activation and increase in vascular permeability (10). The presence of major basic protein in biopsy samples of chronic urticaria (11) makes the eosinophil suspect as an effector cell. Prolonged response to histamine, but not leukotrienes, in the skin of patients with chronic urticaria may suggest abnormal clearance of mediators locally (12).

Table 31.1 Potential Mechanisms of Mast Cell Activation in Urticaria or Angioedema | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recent efforts in studying the pathogenesis of chronic urticaria has resulted in the belief that serological mediators such as autoantibodies or histamine-releasing factors (HRFs) which are not autoantibodies in addition to/or an alteration in mast cell or basophil responsiveness to histamine-releasing agents can lead to chronic urticaria. Evidence for an autoimmune cause of chronic urticaria came to light when it was reported that 14% of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) had antithyroid antibodies (13). Treatment of

these patients with thyroid hormone has not changed the natural course of the disease, but it may have variable benefit to severity and duration of urticarial lesions (14). Because of the association between autoimmune thyroid disease and urticaria, other autoantibodies in patients with chronic urticaria were sought. Greaves reported a 5% to 10% incidence of anti-(IgE) antibodies in these patients (15). Next, the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) was identified and isolated. Shortly thereafter, it was reported that 45% to 50% patients with CIU have anti–IgE-receptor antibodies that bind to the α subunit of the IgE receptor, causing activation of mast cells or basophils (16). A more recent study of 78 patients with CIU found that one-third of patients had functional (histamine releasing) autoantibodies directed against either (17). Patients with CIU and presence of these autoantibodies are now classified as chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU) by some investigators.

these patients with thyroid hormone has not changed the natural course of the disease, but it may have variable benefit to severity and duration of urticarial lesions (14). Because of the association between autoimmune thyroid disease and urticaria, other autoantibodies in patients with chronic urticaria were sought. Greaves reported a 5% to 10% incidence of anti-(IgE) antibodies in these patients (15). Next, the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) was identified and isolated. Shortly thereafter, it was reported that 45% to 50% patients with CIU have anti–IgE-receptor antibodies that bind to the α subunit of the IgE receptor, causing activation of mast cells or basophils (16). A more recent study of 78 patients with CIU found that one-third of patients had functional (histamine releasing) autoantibodies directed against either (17). Patients with CIU and presence of these autoantibodies are now classified as chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU) by some investigators.

The presence and clinical relevance of autoantibodies to FcεRI or IgE can be identified by both in vivo and in vitro tests. The autologous serum skin test (ASST) consists of a cutaneous injection of autologous serum resulting in a wheal-and-flare at 30 minutes; however, healthy patients without urticaria have been found to have positive ASST(18). Due to the occurrence of immunoreactive but nonhistamine releasing autoantibodies in some CIU patients and their presence in patients with autoimmune connective tissue diseases without CIU, immunoassays for these antibodies have not been useful. Instead, methods for measuring the release of histamine have been developed where the sera of patients with CIU is incubated with donor basophils, then measured directly for histamine or indirectly through basophil activation marker CD203c (19). These assays are limited by the variability of releasibility between donor basophils from different sources and it has yet to be proven that the presence of functional autoantibodies in CIU patients are pathogenic.

The suggestion of the presence of a nonantibody HRF such as complement, chemokines, or cytokines, comes from the finding that over 50% of CIU patients do not have autoantibodies. In support of this notion, it has been shown that IgG-depleted serum can cause a positive ASST (20). Evidence for alterations in basophil function comes from the finding of 2 basophil phenotypes in patients with CIU with differing IgE receptor responsiveness (21). In addition to differences in histamine releasability, patients with CIU have been found to have decreased numbers of serum basophils which suggests that basophils are recruited to the skin in CIU (22). This was confirmed by observations that both lesional and nonlesional skin of patients with CAU contained increased basophils after ASST compared to healthy controls (23).

Products from the kinin-generating system are now known to be important in hereditary angioedema (HAE) (24) and angioedema resulting from angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (25). In addition, bradykinin has been reported to be capable of causing a wheal-and-flare reaction when injected into human skin. Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are capable of altering arachidonic acid metabolism and can result in urticaria without specific interaction between IgE and the pharmacologic agent.

Nonspecific factors that may aggravate urticaria include fever, heat, alcohol ingestion, exercise, emotional stress, peri-menopausal status, and hyperthyroidism. Anaphylaxis and urticaria due to progesterone have been described (26) but seem to be exceedingly rare, and progesterone has been used to treat chronic cyclic urticaria and eosinophilia (27). Certain food additives such as tartrazine or monosodium glutamate have been reported to aggravate chronic urticaria (25,28). Many experts experienced in urticaria believe that progesterone is not a cause or a treatment and that food preservatives do not aggravate chronic urticaria. There have been studies showing no relationship between urticaria and monosodium glutamate as well as aspartame (29,30).

Biopsy

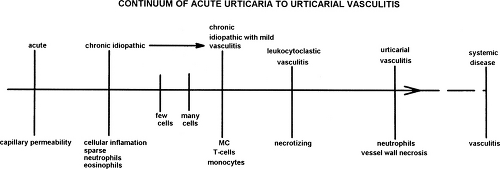

Biopsy of urticarial lesions has accomplished less than expected to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of urticaria, but may help guide therapy in refractory cases. Three major patterns are currently recognized (Table 31.2). Acute and physical urticarias

show only dermal edema without cellular infiltrate, whereas chronic urticaria typically shows a perivascular mononuclear or lymphocytic infiltrate with an increased number of mast cells. Urticarial vasculitis—in which lesions last more than 24 hours, may be purpuric, and may heal with residual hyperpigmentation—show neutrophil infiltration and vessel wall necrosis with or without immunoprotein deposition. A subset of patients (up to 19% in one study) with acute or chronic urticaria will have a neutrophil predominant dermal infiltrate without evidence of vasculitis (31). Further studies may determine if these several pathologic forms of urticaria represent a continuum of disease (Fig. 31.1) or separate pathophysiologic entities.

show only dermal edema without cellular infiltrate, whereas chronic urticaria typically shows a perivascular mononuclear or lymphocytic infiltrate with an increased number of mast cells. Urticarial vasculitis—in which lesions last more than 24 hours, may be purpuric, and may heal with residual hyperpigmentation—show neutrophil infiltration and vessel wall necrosis with or without immunoprotein deposition. A subset of patients (up to 19% in one study) with acute or chronic urticaria will have a neutrophil predominant dermal infiltrate without evidence of vasculitis (31). Further studies may determine if these several pathologic forms of urticaria represent a continuum of disease (Fig. 31.1) or separate pathophysiologic entities.

Figure 31.1 A hypothetical model for describing the range of histology of chronic idiopathic urticaria. |

Table 31.2 Biopsy Patterns of Urticarial and Angioedema Lesions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Studies of the cellular infiltrate of CIU patients both with and without functional antibodies to FcεRIα found no difference in either the type or number of inflammatory cells or the cytokine pattern between the two groups. In addition, the histological findings were similar to that of the late-phase reaction in atopic individuals. CIU skin biopsies demonstrated increased levels of IL-4, IL-5, and INF-γ while late-phase reactions biopsies revealed increased IL-4, IL-5, but not IFN-γ, suggesting the involvement of a mixture of TH1 and TH2 cells or alternatively TH0 cells in CIU (32).

Classification

Classification in terms of known causes is helpful in evaluating patients with urticaria. Table 31.3 presents one classification that may be clinically useful. Additional knowledge of precipitating events or mechanisms may simplify this classification (33).

Table 31.3 Classification of Urticaria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nonimmunologic

Physical Urticaria

The physical urticarias are a unique group that constitute up to 17% of chronic urticarias and several reviews have been published (34–36). They are frequently missed as a cause of chronic urticaria, and more than one type may occur together in the same patient. Most forms, with the exception of delayed pressure urticaria (DPU), occur as simple hives without inflammation, and individual lesions resolve within 24 hours. As a group, they can be reproduced by various physical stimuli that have been standardized in some cases (Table 31.4).

Table 31.4 Test Procedures for Physical and Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dermographism literally means “write on skin.” This phenomenon, also called factitious urticaria, may be detected unexpectedly on routine examination, or patients may complain of pruritus and rash, frequently characterized by linear wheals. When questioned carefully, they may state that itching precedes the rash, causing them to scratch and worsen the condition. The cause of this lesion is unknown. Because it appears in approximately 5% of people, it may be a normal variant. Its onset has been described following severe drug reactions and may be confused with vaginitis in evaluating genital pruritus (37). A delayed form has been recognized with onset of lesions 3 to 8 hours after stimulus to the skin, which may be related to DPU. It may accompany other forms of urticaria. The lesion is readily demonstrated by lightly stroking the skin of an affected patient with a pointed instrument or tongue depressor. This produces erythema, pruritus, and linear streaks of edema or wheal formation. No antigen, however, has been shown to initiate the response, but dermographism has been passively transferred with plasma. Antihistamines usually ameliorate symptoms if they are present. Cutaneous mastocytosis may be considered under the heading of dermographism, because stroking the skin results in significant wheal formation (Darier sign). This disease is characterized by a diffuse increase in cutaneous mast cells. The skin may appear normal, but is usually marked by thickening and accentuated skin folds.

Delayed pressure urticaria, with or without angioedema, is clinically characterized by the gradual onset of wheals or edema in areas where pressure has been applied to the skin. Onset is usually 4 to 6 hours after exposure, but wide variations may be noted. An immediate form of pressure urticaria has been observed. The

lesion of DPU can be reproduced by applying pressure with motion for 20 minutes (38). DPU lesions can be pruritic and/or painful and may be associated with malaise, fever, chills, arthralgias, and leukocytosis. The mechanism of these reactions is unknown, but biopsy samples of lesions show a predmoninantly eosinophilic cell infiltrate located in the deep dermis (39). In addition, increased levels of TNF-α have been found in many cell types of patients with DPU (40). A recent case report demonstrated successful treatment of DPU with anti-TNF-α, suggesting that TNF-α may play an important role in DPU (41). The incidence of DPU has been reported as 2% of all urticarias; however, one recent study has found that 37% of patients with CIU have associated DPU (9,42). Treatment is based on avoidance of situations that precipitate the lesions. Antihistamines are generally ineffective, and a low-dose, alternate-day corticosteroid may be necessary for the more severe cases. NSAIDs (43), dapsone, montelukast, and colchicine have occasionally been helpful in case reports (42).

lesion of DPU can be reproduced by applying pressure with motion for 20 minutes (38). DPU lesions can be pruritic and/or painful and may be associated with malaise, fever, chills, arthralgias, and leukocytosis. The mechanism of these reactions is unknown, but biopsy samples of lesions show a predmoninantly eosinophilic cell infiltrate located in the deep dermis (39). In addition, increased levels of TNF-α have been found in many cell types of patients with DPU (40). A recent case report demonstrated successful treatment of DPU with anti-TNF-α, suggesting that TNF-α may play an important role in DPU (41). The incidence of DPU has been reported as 2% of all urticarias; however, one recent study has found that 37% of patients with CIU have associated DPU (9,42). Treatment is based on avoidance of situations that precipitate the lesions. Antihistamines are generally ineffective, and a low-dose, alternate-day corticosteroid may be necessary for the more severe cases. NSAIDs (43), dapsone, montelukast, and colchicine have occasionally been helpful in case reports (42).

Solar urticaria is clinically characterized by development of pruritus, erythema, and edema within minutes of exposure to light. The lesions are typically present only in exposed areas. Diagnosis can be established by using broad-spectrum light with various filters or a spectrodermograph to document the eliciting wavelength (44). Treatment includes avoidance of sunlight and use of protective clothing and various sunscreens or blockers, depending on the wavelength eliciting the lesion (45). An antihistamine taken 1 hour before exposure may be helpful in some forms, and induction of tolerance is possible.

Cholinergic urticaria (generalized heat), a common form of urticaria (5% to 7%), especially in teenagers and young adults (11.2%), is clinically characterized by small, punctate hives surrounded by an erythematous flare, the so-called “fried egg” appearance. These lesions may be clustered initially, but can coalesce and usually become generalized in distribution, primarily over the upper trunk and arms. Pruritus is generally severe. The onset of the rash is frequently associated with hot showers, sudden temperature change, exercise, sweating, or anxiety. A separate entity with similar characteristic lesions induced by cold has been described (46). Rarely, systemic symptoms may occur. The mechanism of this reaction is not certain, but cholinergically mediated thermodysregulation resulting in a neurogenic reflex has been postulated, because it can be reproduced by increasing core body temperature by 0.7°C to 1°C (47). Histamine and other mast cell mediators have been documented in some patients (48) and increased

muscarinic receptors have been reported in lesional sites of a patient with cholinergic urticaria (49). The appearance and description of the rash are highly characteristic and are reproduced by an intradermal methacholine skin test, but only in one-third of the patients. Exercise in an occlusive suit or submersion in a warm bath is a more sensitive method of reproducing the urticaria. Passive heat can be used to differentiate this syndrome from exercise-induced urticaria or anaphylaxis. Nonsedating antihistamines are the treatment of choice; however, some patients require combination treatment including a first-generation antihistamine such as hydroxyzine.

muscarinic receptors have been reported in lesional sites of a patient with cholinergic urticaria (49). The appearance and description of the rash are highly characteristic and are reproduced by an intradermal methacholine skin test, but only in one-third of the patients. Exercise in an occlusive suit or submersion in a warm bath is a more sensitive method of reproducing the urticaria. Passive heat can be used to differentiate this syndrome from exercise-induced urticaria or anaphylaxis. Nonsedating antihistamines are the treatment of choice; however, some patients require combination treatment including a first-generation antihistamine such as hydroxyzine.

A form of “autonomic” urticaria called adrenergic urticaria has been described and can be reproduced by intracutaneous injection of noradrenaline (3–10 ng in 0.02 ml saline) (50). This unique form of urticaria is characterized by a “halo” of white skin surrounding a small papule. It may have been previously misdiagnosed as cholinergic urticaria because of its small lesions and its association with stress. In this case, however, relief can be provided with β blockers.

Local heat urticaria, a rare form of heat urticaria (51), may be demonstrated by applying localized heat to the skin. A familial localized heat urticaria also has been reported (52) and is manifested by a delay in onset of urticarial lesions of 4 to 6 hours following local heat exposure.

Cold urticaria is clinically characterized by the rapid onset of urticaria or angioedema after cold exposure. Lesions are generally localized to exposed areas, but sudden total body exposure, as in swimming, may cause hypotension and result in death (53). Although usually idiopathic (primary acquired cold urticaria), cold urticaria has been associated with cryoglobulinemia, cryofibrinogenemia, cold agglutinin disease, and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (secondary acquired cold urticaria) (54

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree