Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Ikuo Hirano

Nirmala Gonsalves

Anne Marie Ditto

Epidemiology and Demographic Characteristics

Over the last several years, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has become increasingly recognized as an important disease by allergists, internists, and gastroenterologists caring for both pediatric and adult patients. Although often abbreviated as EE in the literature, there is movement to use EoE to refer to eosinophilic esophagitis since EE has long been used by gastroenterologists to refer to erosive esophagitis. EoE may occur in isolation or in conjunction with eosinophilic gastroenteritis (1).

Previously considered a rare condition, there has been a dramatic increase in reports of EoE from North and South America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East over the last several years (2–11). The cause for this rise is likely a combination of an increasing incidence of EoE and a growing awareness of the condition among gastroenterologists, allergists, and pathologists. Noel et al. suggest that the incidence of EoE has been rising in a population of children residing in Hamilton, Ohio. In 2000, the authors estimated the incidence to be 0.91 per 10,000 with a prevalence of 1 per 10,000 compared to 1.7 in 10,000 and a prevalence of 10.4 in 10,000 in 2007 (12). Straumann et al. studied a population of adults in Olten County, Switzerland, and found a similar trend. They estimated an incidence of 0.15 cases per 10,000 adult inhabitants with a prevalence of 3 per 10,000 inhabitants of their catchment area in Switzerland (13). These numbers are likely to underestimate the true incidence and prevalence of EoE in the general population since these data are based on patients with symptoms sufficient to warrant endoscopy. A population-based study in Sweden randomly surveyed 3,000 adult members of the population, and 1,000 healthy adults underwent endoscopy with esophageal biopsies. This group found that histologic eosinophilia meeting their criteria for definite and probable EoE was present in 1% of the population (14). These numbers suggest that EoE is becoming as common as other immunologic disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (15). In addition, increasing publications about EoE in the last several years are contributing to the awareness of this condition in both the gastroenterology and pathology community (9). For instance a PubMed search of articles using the term eosinophilic esophagitis resulted in 365 publications from 2000 to November 2008 compared to only 38 publications prior to this time.

Eosinophilic esophagitis has a male predilection. Results from 323 adult patients from 13 studies observed that 76% were males with a mean age of 38 years (range 14 to 89 years). Results from 754 pediatric patients from 16 studies found that 66% were male with a mean age of 8.6 years (range 0.5 to 21.1 years) (16). EoE has been described in patients with varied ethnicities including those of Caucasian, African American, Latin-American, and Asian descent (16). One pediatric review suggested that there was a racial predilection with 94% of the patients being Caucasian (17). A familial pattern has been recognized in the pediatric population. In a case series of 381 children with EoE, 5% of patients had siblings with EoE and 7% had a parent with either an esophageal stricture or a known diagnosis of EoE (18). One study showed that eotaxin-3, a gene encoding an eosinophil-specific chemoattractant, was the most highly induced gene in pediatric EoE patients (19). This finding supports the previous reports suggesting a potential genetic predisposition to EoE. Although formal genetic studies have not yet been pursued in adults, several case reports also suggest familial clustering of this condition in adults; therefore, a workup of patients should include a thorough family history (20–22).

Clinical Features

The clinical features of EoE in both adults and children are described in Table 40.1. As with other diseases, some age-related differences in clinical presentation are noted. The most common presenting symptoms in adults include dysphagia, food impaction, heartburn, and chest pain (16,23). In one study, as many as 50% of adults presenting with food impaction were ultimately diagnosed with EoE (24). In children, the most common presenting symptoms include vomiting,

heartburn, regurgitation, emesis, and abdominal pain (16,18). While younger children rarely present with dysphagia and food impaction, these presentations were more commonly seen in older children and adolescents (12,25). In adults, this diagnosis has often been overlooked and many patients have had endoscopies with alternate diagnoses, including Schatzki rings or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) prior to a diagnosis of EoE (26,27). In many cases, these patients had undergone repeated endoscopies, esophageal dilations, and a delay in the institution of appropriate medical therapy (26,27). In previous years, the presence of eosinophils in esophageal mucosal biopsies was equated with GERD and therefore some specimens may have been classified as reflux (28). Due to this potential overlap, gastroenterologists who suspect a diagnosis of EoE should specifically request tissue eosinophil counts by the pathologist to help differentiate this diagnosis from GERD.

heartburn, regurgitation, emesis, and abdominal pain (16,18). While younger children rarely present with dysphagia and food impaction, these presentations were more commonly seen in older children and adolescents (12,25). In adults, this diagnosis has often been overlooked and many patients have had endoscopies with alternate diagnoses, including Schatzki rings or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) prior to a diagnosis of EoE (26,27). In many cases, these patients had undergone repeated endoscopies, esophageal dilations, and a delay in the institution of appropriate medical therapy (26,27). In previous years, the presence of eosinophils in esophageal mucosal biopsies was equated with GERD and therefore some specimens may have been classified as reflux (28). Due to this potential overlap, gastroenterologists who suspect a diagnosis of EoE should specifically request tissue eosinophil counts by the pathologist to help differentiate this diagnosis from GERD.

Table 40.1 Clinical Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children and Adults | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

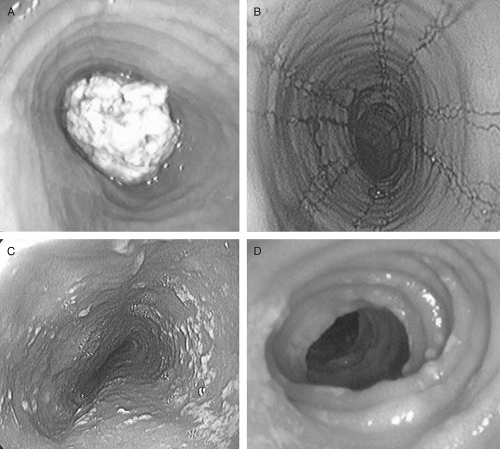

Endoscopic Findings

The most common endoscopic features in adults with EoE include linear or longitudinal furrows (80%), mucosal rings (64%), small caliber esophagus (28%), white plaques and/or exudates (16%), and strictures (12%) (23) (Fig. 40.1). In a large clinical series of 381 children,

the most common endoscopic features were linear furrows (41%), normal appearance (32%), esophageal rings (12%), and white plaques (15%) (18). It is important to note that the classic endoscopic features may be subtle and missed during endoscopy (16). Therefore, it is suggested that biopsies be taken for the clinical indication of unexplained dysphagia, refractory heartburn, or chest pain despite normal endoscopic findings (16).

the most common endoscopic features were linear furrows (41%), normal appearance (32%), esophageal rings (12%), and white plaques (15%) (18). It is important to note that the classic endoscopic features may be subtle and missed during endoscopy (16). Therefore, it is suggested that biopsies be taken for the clinical indication of unexplained dysphagia, refractory heartburn, or chest pain despite normal endoscopic findings (16).

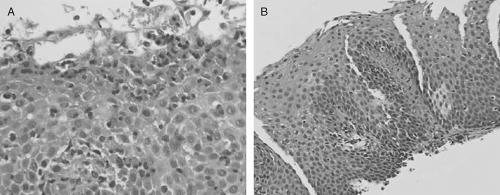

Histologic Features

While certain endoscopic features are characteristic of EoE, this condition is ultimately diagnosed by obtaining biopsy specimens which demonstrate histologic findings of increased intramucosal eosinophils in the esophagus without concomitant eosinophilic infiltration in the stomach or duodenum (16) (Figure 40.2). Other histologic features of this condition include superficial layering of the eosinophils, eosinophilic microabscesses (clusters of ≥4 eosinophils), intercellular edema, and degranulation of eosinophils. Other inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and mast cells may be present in the epithelium (29–31). Another histologic finding in EoE is epithelial hyperplasia, defined by papillary height elongation and basal zone proliferation (31). Epithelial hyperplasia is also a cardinal feature of the histopathology of reflux esophagitis. Studies have also shown presence of subepithelial fibrosis in biopsies of adults and children with eosinophilic esophagitis suggesting that deeper layers of the esophagus may be involved (3,32,34). Involvement of deeper layers of the esophagus has further been supported by the use of endoscopic ultrasound (35–37). It is speculated that this mucosal and submucosal fibrosis may lead to esophageal

remodeling and decreased compliance of the esophagus thus contributing to the symptoms of dysphagia even in the absence of an identifiable stricture.

remodeling and decreased compliance of the esophagus thus contributing to the symptoms of dysphagia even in the absence of an identifiable stricture.

Although a single diagnostic threshold of eosinophil density has not been determined, a recent consensus statement suggests using a threshold value of ≥15 eosinophils per high power field to diagnose EoE (16). It has also been demonstrated that the eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus may not be evenly distributed within the esophagus (27). Therefore, it is suggested that biopsies be obtained from both the proximal and distal esophagus to obtain a higher diagnostic yield and perhaps increase the specificity of the diagnosis. A retrospective study of adult EoE patients found that obtaining more than five biopsies maximizes the sensitivity based on a diagnostic threshold of ≥15 eosinophils per high power field in the adult population (27). A follow-up study using a pediatric cohort demonstrated that 3 biopsies yielded a diagnosis of EoE in 97% of patients (38). In both the adult and pediatric studies, biopsies taken of only the proximal or distal esophagus missed the diagnosis in up to 20% of cases emphasizing the importance of taking biopsies from different locations.

Diagnostic Criteria

Recent consensus recommendations based on a systematic review of the literature and expert opinion have led to the following diagnostic criteria. EoE is a clinico-pathological disease characterized by (a) the presence of symptoms including but not limited to dysphagia and food impaction in adults and feeding intolerance and GERD symptoms in children, (b) ≥15 eosinophils per high power field in the esophageal tissue, and (c) exclusion of other disorders associated with similar clinical, histologic, or endoscopic features such as GERD with either the use of high dose acid suppression prior to biopsy procurement or normal pH monitoring (16).

Additional Diagnostic Testing

Intraesophageal pH Testing

There have been nine adult studies and 11 pediatric studies reporting data from pH monitoring. Of 228 adult patients, 40% had pH monitoring with normal results in 82% of patients. Of 223 children, 78% had pH monitoring with normal results in 90% of patients (16).

Radiography

Radiologic studies such as barium esophagrams may be used in the workup of patients with EoE but are sometimes nondiagnostic. A recent study that correlated endoscopic and radiologic features in EoE demonstrated that both esophageal strictures as well as esophageal rings may be identified on barium studies of patients with EoE (8). In addition to identifying a stricture, the use of upper GI contrast studies may better characterize the length of a stricture as well as its caliber. This information may be helpful prior to subsequent upper endoscopy by alerting the endoscopist to use a smaller caliber endoscope or to proceed more cautiously with passage of the endoscope (16).

Manometry

Esophageal manometry was studied in 77 adults in seven studies and 14 children in three studies (16). Esophageal manometry was found to be abnormal in 41 of 77 adult patients. In the adults, the lower esophageal sphincter was normal in 66 of 77, hypotensive in 10 of 77, and hypertensive in 1 patient. Peristaltic abnormalities were seen in 30 of 77 patients and 28 of 30 patients had nonspecific peristaltic abnormalities. One patient each had diffuse esophageal spasm and nutcracker esophagus, which is defined by peristaltic pressure >180 mm Hg. Compared to these abnormalities in

adults, all 14 children had a normal esophageal manometry. A recent study by Chen et al. used the newer technique of high resolution manometry in 24 adult patients with EoE (39). The most common abnormality noted was elevation in peristaltic velocity. Some patients also had failed esophageal peristalsis, repetitive simultaneous esophageal contractions, and impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Such manometric abnormalities may provide an explanation for the symptoms of dysphagia that occur in patients without a discernable esophageal stricture.

adults, all 14 children had a normal esophageal manometry. A recent study by Chen et al. used the newer technique of high resolution manometry in 24 adult patients with EoE (39). The most common abnormality noted was elevation in peristaltic velocity. Some patients also had failed esophageal peristalsis, repetitive simultaneous esophageal contractions, and impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Such manometric abnormalities may provide an explanation for the symptoms of dysphagia that occur in patients without a discernable esophageal stricture.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of EoE is not known although it is thought to be allergic owing to the prominent presence of eosinophils as well as pathologic findings that share similarity with other allergic diseases such as asthma, e.g., thickened mucosa and basal layer hyperplasia. TH2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, Il-5 and Il-13 have been shown to be upregulated (40) with IL-5 induced tissue specific eosinophilia causing remodeling (41,42) as well as reversibility of Il-13 induction with glucocorticoids (43). Blanchard et al. showed marked upregulation of eotaxin-3 gene expression in patients with EoE and interaction between eotaxin-3 and its receptor CCR 3 in EoE (19). Furthermore, peripheral blood eosinophils with CCR3 expression and increased CD4+ cells expressing IL-5 have been demonstrated. These correlate with eosinophils in the esophagus and also with disease activity, being lower in patients whose disease is in remission (44). Kirsch et al. demonstrated increased numbers of mast cells and activation of mucosal mast cells distinguishing EoE from GERD (45). In addition, there is a high incidence of atopic disease such as allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma (46).

Allergens

Although EoE is thought to be allergic, the allergen remains elusive. The concept of food as the allergenic cause was first introduced by Kelly et al. who described 10 children with severe GERD symptoms unresponsive to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy (47). Eight patients had resolution and 2 had improvement in symptoms when placed on an elemental diet (ELED) for 6 weeks (Neocate One+, SHS North America, Gaithersburg, MD; EleCare, Ross Pediatrics, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Histologically patients improved as well; eosinophil numbers decreased from a median of 41 per hpf (range 15 to 100) to a median of 0.5 (range 0 to 22) eos/hpf. The demonstration of recurrent symptoms on food reintroduction added credence to the role of food allergy. Markowitz et al. showed similar results in a study of 51 children diagnosed with EoE, using strict criteria to rule out GERD (48). For 3 months, 346 children with symptoms of GERD were treated with a PPI. Those who clinically responded to empiric PPI therapy or demonstrated an abnormal 24-hour pH study after treatment were excluded from the study. The remaining 51 children were treated with an ELED for 4 weeks with marked response. Eosinophil counts per hpf decreased on average from 34 to 1. Symptoms recurred with reintroduction of food. Similar results have been reproduced in several studies in children from multiple centers with larger cohorts showing resolution of symptoms and histologic evidence of EoE (18,49,51). However, elemental diets are unpalatable and very difficult to maintain and oftentimes require tube feedings. In the study by Liacouras et al., 80% of the children were fed by nasogastric tube and eight patients were unable to tolerate the diet (18). This poor tolerability has led to trials of empiric and allergy testing directed food elimination. Kagalwalla et al. retrospectively studied children with EoE, comparing those treated with an ELED to those treated with a diet eliminating the eight (six) most common food groups involved in allergy: nuts (tree nuts and peanuts), seafood (fish and shellfish), wheat, soy, milk, and eggs. This empiric approach was termed the six food elimination diet (SFED) (49). There were 60 children studied, 35 on SFED, and 25 on ELED. Twenty five of the 35 patients (69%) on SFED and 22 of 25 (88%) on ELED showed improvement in symptoms and resultant eosinophil counts ≤ 10 per hpf.

Work has been done to try to identify culprit foods for more directed rather than empiric food elimination. However, identification of the food with traditional methods of testing for food allergy has had limited success. Since EoE patients do not have reactions that are typical of immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergic reactions such as urticaria or anaphylaxis, and since reactions may not be immediate, it has been difficult to identify responsible foods by history. In addition, studies show that symptoms do not necessarily correlate with disease (39). Children, however, tend to have more immediate symptoms such as vomiting and it is possible that their histories and allergy test results may be more reliable. Traditional tests used for determining food allergy, skin-prick test (SPT) and ELISA ImmunoCAP, are used to detect IgE antibodies and therefore may have a limited role in predicting food allergens in EoE. Furthermore, the sensitivity, specificity, as well as positive and negative predictive values for these tests, have shown substantial variability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree