Urothelial Neoplasms With Inverted Growth Patterns

INVERTED UROTHELIAL PAPILLOMA

This is a benign tumor of the urinary bladder constituting less than 1% of urothelial neoplasms. Cystoscopically, they appear as solitary, raised, pedunculated, or, rarely, polypoid lesions with a smooth surface (1). Lesions occur in a wide age range of patients (10 to 94 years), with a peak frequency in the sixth and seventh decades; there is a striking male predilection (2, 3), as is the case with most urothelial neoplasms. Tumor size varies from small (less than 1 to 50 mm, mean 12.8 mm). Most lesions are solitary (less than 5% are multifocal) and present with hematuria (4).

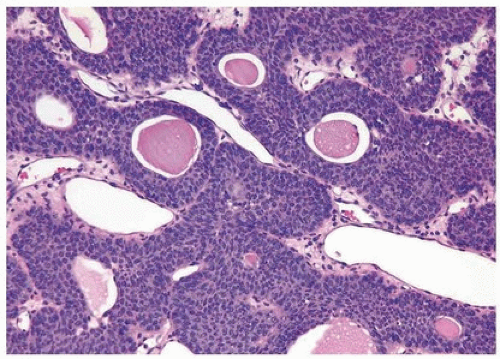

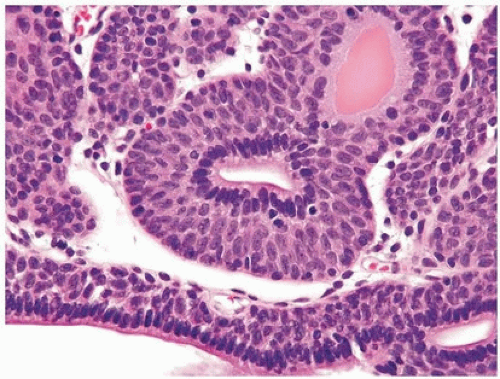

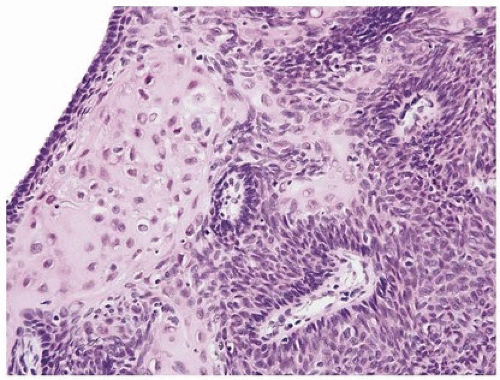

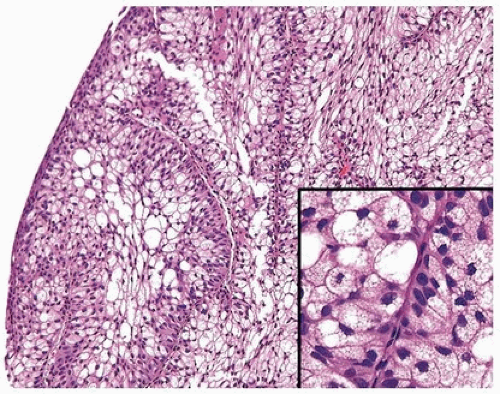

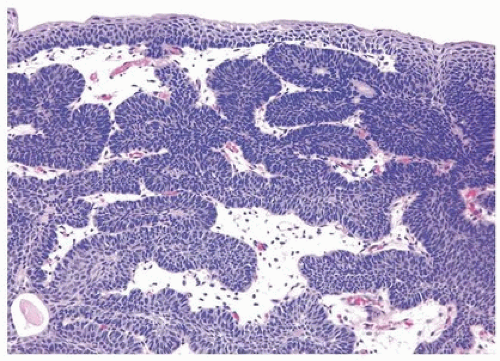

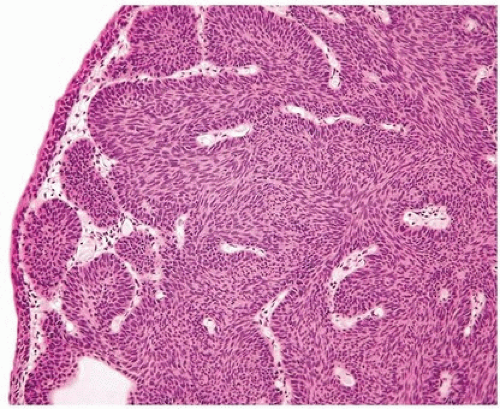

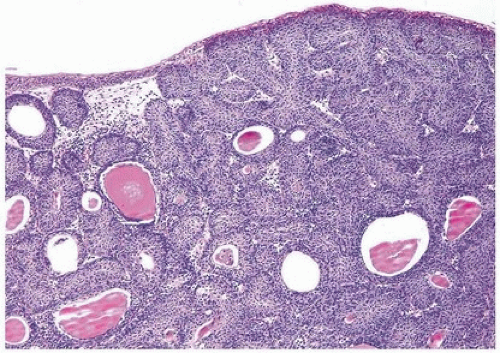

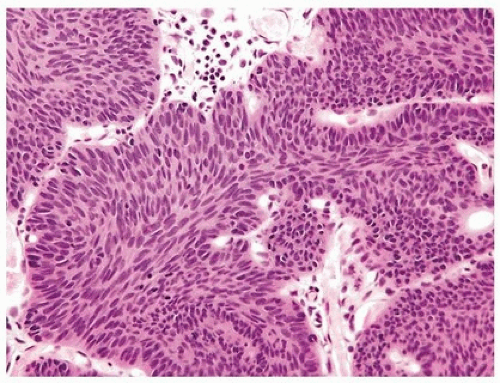

Histologically, two variations have been described: trabecular and glandular. The trabecular type is the classic lesion that most pathologists think of when considering inverted papilloma, histologically showing cords and trabeculae of cells arising from a smooth surface and invaginating into the lamina propria (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.3) (efigs 4.1-4.22). Because these endophytic proliferations represent inversion of papillae, the periphery is composed of darker cells that are often palisaded (the basal cells), and the central portions show maturing cells occasionally with superficial cells lining central luminal spaces filled with colloid material (Figs. 4.4, 4.5, 4.6). It is not uncommon to see focal nonkeratinizing squamous and occasionally true glandular differentiation (so-called glandular type) within the center of the urothelial cords (Figs. 4.7, 4.8). In the latter setting, mimicry with florid cystitis cystica is considerable, and we rely on the overall organization and architecture of the lesion to designate a lesion as inverted neoplasia. The surrounding stroma is fibrotic and nonreactive without inflammation.

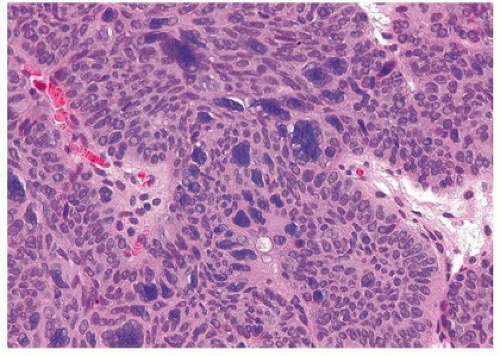

Cytologic atypia is minimal to absent, although occasionally degenerative atypia may be present, albeit focally (Fig. 4.9) (efigs 4.23, 4.24). Exceptional cases may have the classic features of benign inverted urothelial papilloma, yet have focal nondegenerative atypia. One of the authors has studied inverted papillomas with very focal atypia subdivided into the following groups: (a) areas containing prominent nucleoli, (b) foci with atypical squamous features, and (c) foci with areas of dysplasia,

approaching the level of carcinoma in situ (Fig. 4.10) (efigs 4.25-4.32). These lesions are controversial, as some experts consider that any neoplastic (nondegenerative) atypia should lead to the diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma with inverted features. Others consider that if the lesion is otherwise architecturally and cytologically classic for inverted papilloma with the exception of focal cytological atypia, it is justified to diagnose these lesions as inverted papilloma with a comment on the atypia. In the only study to investigate this phenomenon, albeit with only a few cases and limited follow-up, the clinical course was benign (5). Regardless of the nomenclature used, any atypical features in an inverted urothelial papilloma warrant periodic cystoscopic follow-up.

approaching the level of carcinoma in situ (Fig. 4.10) (efigs 4.25-4.32). These lesions are controversial, as some experts consider that any neoplastic (nondegenerative) atypia should lead to the diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma with inverted features. Others consider that if the lesion is otherwise architecturally and cytologically classic for inverted papilloma with the exception of focal cytological atypia, it is justified to diagnose these lesions as inverted papilloma with a comment on the atypia. In the only study to investigate this phenomenon, albeit with only a few cases and limited follow-up, the clinical course was benign (5). Regardless of the nomenclature used, any atypical features in an inverted urothelial papilloma warrant periodic cystoscopic follow-up.

FIGURE 4.1 Inverted urothelial papilloma with focal downgrowth from overlying benign urothelium (upper right). |

FIGURE 4.2 Inverted urothelial papilloma with undermining overlying benign urothelium. There is prominent spindling in this case with peripheral palisading. |

FIGURE 4.3 Inverted urothelial papilloma with undermining overlying benign urothelium. Note colloid cysts. |

FIGURE 4.4 Inverted urothelial papilloma with cords of epithelium showing peripheral palisading and central streaming of urothelium parallel to the cords. High power of Figure 4.2. |

FIGURE 4.5 Inverted urothelial papilloma with peripheral palisading and central streaming of urothelium. |

Mitotic figures are rare and are only seen at the periphery of the trabeculae. The trabeculae are orderly, of relatively uniform width, with considerable ramifications and interanastomosis. The urothelium in the center of the trabeculae tends to stream parallel to the cords. Occasionally, there may be marked von Brunn nest proliferation in the adjacent mucosa. Paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation is exceptionally rare (6). Other unusual variants include those with xanthomatous or vacuolated cytoplasm (Figs. 4.11, 4.12) (6).

Inverted urothelial papillomas may have focal polypoid exophytic areas, yet lack true papillae (Figs. 4.13, 4.14) (efig 4.19). Within these broader projections are solid nests and cords of urothelium, cytologically characteristic of inverted urothelial papilloma, differing from a central fibrovascular core lined by urothelium seen in urothelial carcinoma and exophytic urothelial papilloma. Exceptionally, classic inverted papillomas may have one or two small apparently true fronds; in these cases, a diagnosis of inverted papilloma is still acceptable as the fronds may represent a tangential section off of a polypoid growth (Fig. 4.15). In rare cases, there may be the classic findings of benign inverted urothelial papilloma with areas typical of exophytic urothelial papilloma. These cases are referred to as mixed inverted and exophytic urothelial papilloma. There are only

anecdotal data on the behavior of these hybrid lesions, most behaving indolently although it is recommended that they be followed as if they had an exophytic papilloma with repeat periodic cystoscopic examinations (7).

anecdotal data on the behavior of these hybrid lesions, most behaving indolently although it is recommended that they be followed as if they had an exophytic papilloma with repeat periodic cystoscopic examinations (7).

Inverted urothelial papilloma is a benign neoplasm, which if completely resected does not need routine cystoscopic follow-up, in contrast to what is performed for urothelial carcinoma and exophytic urothelial papilloma. Older studies suggested that inverted urothelial papilloma, especially in the upper urinary tract, was associated with an increased likelihood of prior, concurrent, or subsequent urothelial carcinoma (8, 9). However, multiple more recent studies have not shown an increased risk of urothelial carcinoma (10, 11). A recent review of the literature of over 348 cases has shown that 1.7% of inverted papillomas of the bladder had previous urothelial carcinoma, 1.4% had synchronous urothelial carcinoma, and 1.1% had subsequent urothelial carcinoma; time to recurrence was less than 45 months, average approximately 28 months (4).

Bladder urothelial papillomas are typically not associated with urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract such that surveillance of the upper tract in patients with inverted papilloma of the lower tract is not deemed necessary (4). Several recent studies have explored molecular changes in inverted lesions (studied by immunohistochemistry, fluorescence, in situ hybridization, microsatellite and loss of heterozygosity analysis, and mutational analyses), but none of these studies to date have applications to routine diagnostic surgical pathology, although they support the benign nature of these lesions (5, 11, 12, 13, 14). HRAS and fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutations have been detected in a small subset of cases (5, 15).

Bladder urothelial papillomas are typically not associated with urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract such that surveillance of the upper tract in patients with inverted papilloma of the lower tract is not deemed necessary (4). Several recent studies have explored molecular changes in inverted lesions (studied by immunohistochemistry, fluorescence, in situ hybridization, microsatellite and loss of heterozygosity analysis, and mutational analyses), but none of these studies to date have applications to routine diagnostic surgical pathology, although they support the benign nature of these lesions (5, 11, 12, 13, 14). HRAS and fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutations have been detected in a small subset of cases (5, 15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree