Because of its rarity and high curability, progress in advancing therapeutics in Burkitt lymphoma (BL) has been difficult. Over recent years, several new mutations that cooperate with MYC have been identified, and this has paved the way for testing novel agents in the disease. One of the challenges of most standard approaches typically used is severe treatment-related toxicity that often leads to discontinuation of therapy. To that point, there has been recent success developing intermediate intensity approaches that are well tolerated in all patient groups and maintain high cure rates in a multicenter setting.

Key points

- •

While Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is highly curable with short duration, intensive therapies in children these are poorly tolerated in middle-aged and older adults and immunosuppressed patients.

- •

Some novel less intensive approaches that maintain high cure rates while significantly decreasing treatment-related toxicity compared with traditional strategies are promising.

- •

There have been great strides in the molecular elucidation of BL that have provided several new targets for novel drug development in the disease.

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL), first described by Denis Burkitt in African children over 50 years ago, is a rare and highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma. In Burkitt’s initial paper, he reported unusual jaw tumors associated with a specific distribution pattern of anatomic sites in a group of 38 Ugandan children. This endemic variant, which was the first to be described, occurs in equatorial Africa and some other specific regions of the world, peaks in incidence in 4- to 7-year–old children, and has a predilection for males ( Table 1 ). Two other epidemiologic variants are recognized. Sporadic BL typically affects children and young adults, presents worldwide, and is the most common variant in the Western world. Immunodeficiency-associated BL occurs in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and is approximately 1000 times more common in HIV-infected individuals compared with HIV-negative counterparts. Over recent years, the understanding of the biology of BL has advanced significantly with the identification of novel mutations that cooperate with MYC , and there has also been therapeutic progress with the development of less toxic strategies that maintain the high cure rates of historical high-dose, intensive strategies.

| Endemic | Sporadic | HIV-Associated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Equatorial Africa and Papua, New Guinea Geographic association with malaria | Worldwide | Worldwide |

| Incidence | 5–10 cases per 100,000 population | 2–3 cases per million population | 6 per 1000 AIDS cases |

| Age and Gender | Malignancy of childhood | Malignancy of childhood and young adults | Malignancy of adults |

| Peak Incidence: 4–7 y | Median age: 30 y | Median age: 44 y | |

| Male:female ratio of 2: 1 | Male:female ratio of 2–3:1 | Associated with higher CD4 counts >100/mm 3 | |

| EBV association | 100% | 25%–40% | 25%–40% |

| Genomics | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 40%; CCND mutations 1.8% | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 70%; CCND mutations 38% | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 67%; CCND mutations 67% |

| Clinical Presentation | Jaw and facial bones in approximately 50%; Also involves mesentery and gonads Increased risk of CNS dissemination | Abdomen most common presentation often involving the ileo-cecal region Other extranodal sites include bone marrow, ovaries, kidneys, and breasts Increased risk of CNS dissemination | Nodal presentation most common with occasional bone marrow Increased risk of CNS dissemination |

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL), first described by Denis Burkitt in African children over 50 years ago, is a rare and highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma. In Burkitt’s initial paper, he reported unusual jaw tumors associated with a specific distribution pattern of anatomic sites in a group of 38 Ugandan children. This endemic variant, which was the first to be described, occurs in equatorial Africa and some other specific regions of the world, peaks in incidence in 4- to 7-year–old children, and has a predilection for males ( Table 1 ). Two other epidemiologic variants are recognized. Sporadic BL typically affects children and young adults, presents worldwide, and is the most common variant in the Western world. Immunodeficiency-associated BL occurs in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and is approximately 1000 times more common in HIV-infected individuals compared with HIV-negative counterparts. Over recent years, the understanding of the biology of BL has advanced significantly with the identification of novel mutations that cooperate with MYC , and there has also been therapeutic progress with the development of less toxic strategies that maintain the high cure rates of historical high-dose, intensive strategies.

| Endemic | Sporadic | HIV-Associated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Equatorial Africa and Papua, New Guinea Geographic association with malaria | Worldwide | Worldwide |

| Incidence | 5–10 cases per 100,000 population | 2–3 cases per million population | 6 per 1000 AIDS cases |

| Age and Gender | Malignancy of childhood | Malignancy of childhood and young adults | Malignancy of adults |

| Peak Incidence: 4–7 y | Median age: 30 y | Median age: 44 y | |

| Male:female ratio of 2: 1 | Male:female ratio of 2–3:1 | Associated with higher CD4 counts >100/mm 3 | |

| EBV association | 100% | 25%–40% | 25%–40% |

| Genomics | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 40%; CCND mutations 1.8% | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 70%; CCND mutations 38% | MYC mutation 100%; ID3 and/or TCF3 mutations 67%; CCND mutations 67% |

| Clinical Presentation | Jaw and facial bones in approximately 50%; Also involves mesentery and gonads Increased risk of CNS dissemination | Abdomen most common presentation often involving the ileo-cecal region Other extranodal sites include bone marrow, ovaries, kidneys, and breasts Increased risk of CNS dissemination | Nodal presentation most common with occasional bone marrow Increased risk of CNS dissemination |

Pathobiology of Burkitt lymphoma

The pathobiology of BL is unique and distinct from that of other aggressive B-cell lymphomas. BL is characterized by an extremely high proliferation fraction and a high fraction of apoptosis, and this accounts for its starry sky appearance at low magnification under the microscope. The cells are intermediate in size, have little pleomorphism, and contain basophilic cytoplasm that contains small vacuoles and characteristically round nuclei with little variation in size and shape. The nuclear chromatin is granular and contains small nucleoli with frequent mitoses. Biologically, BL is derived from a germinal center B cell, and the cells are positive for CD10, BCL6, CD20, CD79a, and CD45. The cells are negative for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) as well as BCL2. The growth fraction as measured by Ki67 staining approaches 100%. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is virtually always detected in endemic BL and is present in 25% to 40% of sporadic and immunodeficiency-associated cases. Typically, latency type 1 is observed with restricted EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) expression, and there is evidence for EBV’s oncogenic role. In endemic BL, EBV has been shown to contribute to genomic instability, and interestingly, cases are also linked to malaria prevalence. The incidence is highest in people with high titers of Plasmodium falciparum .

Virtually all cases of BL harbor a MYC translocation—usually at 8q24—and leading to deregulation of the MYC gene. In over 80% of cases, the translocation partner is the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus on chromosome 14; in the remaining cases, κ and λ light chain loci on chromosomes 2 and 22 are involved. MYC breakpoints can vary in their location between sporadic and endemic cases, suggesting that there may be some distinct pathogenetic mechanisms at play depending on the epidemiologic variant. Recently, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) studies have demonstrated that other genes in addition to MYC are frequently mutated in sporadic BL cases. In approximately 70% of cases, there are mutations in TCF3 or its negative regulator ID3 , which encodes a protein that blocks TCF3 action. Thirty-eight percent of sporadic cases harbor a mutation in CCND3 , which is activated by TCF3 and encodes cyclin D3, which promotes cell cycle progression. TCF3 and/or ID3 mutations are found in 67% and 40% of HIV-associated and endemic cases, respectively, and the ongoing Burkitt lymphoma Genome Sequencing Project (BLGSP) aims to further characterize the genomics of these different variants ( https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/cgci/projects/burkitt-lymphoma ). Gene expression profiling studies have revealed that BL cases have a distinct molecular signature that is derived from a germinal center B-cell. There is high expression of c- MYC target genes as well as germinal center-associated B-cell genes. Low expression of MHC class 1 molecules and NF-kappa B target genes is characteristic. In these molecular studies, a subset of aggressive B-cell lymphomas was identified that were diagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by current classification criteria but by gene expression, clearly fell into the BL category. Given that BL does not respond well to CHOP-based treatments, this distinction by molecular profiling is important, and gene expression profiling may be useful in rare cases that would otherwise be diagnosed as DLBCL. Additionally, there are cases with a profile intermediate between that of DLBCL and BL; these cases typically harbor MYC and have a poor outcome with CHOP-based regimens.

Recently, lymphomas that have intermediate morphologic features between DLBCL and BL (B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and BL) have been identified. Many of these were previously classified as Burkitt-like lymphoma. Although they are distinct from BL, they share many genetic and clinical features with the former, although there is no preferential predilection for the ileo-cecal region or jaws.

Clinical presentation and work-up

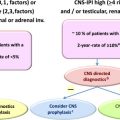

The clinical presentation of BL is variable and depends on the epidemiologic variant and other factors. In endemic BL, patients commonly present with jaw and other facial disease, and other extranodal sites of involvement include the ileum and cecum, gonads, kidneys, and breasts. The ileo-cecal area is the most common site of disease involvement in sporadic BL, and unlike endemic BL jaw involvement, is very rare. In immunodeficiency-associated BL, involvement of the ileum and cecum, lymph nodes, and bone marrow is commonly observed. Central nervous system (CNS) disease may occur at presentation with all variants, particularly when there is advanced-stage disease, and leptomeningeal rather than parenchymal brain involvement is typically seen. Patients often present with advanced-stage and bulky disease caused by the short doubling time of the tumor. It is common for patients to develop tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) after the institution of therapy, and this needs to be anticipated.

It is critical that the histologic diagnosis is made by a hematopathologist with expertise in the diagnosis of lymphoma, as it may be challenging in some cases to distinguish BL from other aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Laboratory tests should include routine hematology and biochemistry panels to include lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid, and testing for HIV and hepatitis B should be performed routinely. Staging should include computed tomography imaging with or without positron emission tomography, and a bone marrow biopsy is essential. A lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis by cytology and flow cytometry should also be performed.

Therapeutic approach to Burkitt lymphoma

BL is a systemic disease that requires chemotherapy for all disease stages. In early development of therapeutic strategies for BL, the high proliferation rate of the tumor and the risk of kinetic failures in between cycles of therapy were deemed to be key to overcome, and therefore early strategies, modeled on approaches in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), employed short-duration, dose-intensive, multiagent regimens. Standard approaches today typically include multiple chemotherapy agents administered in alternating cycles. These agents are administered in a variety of combinations and schedules, indicating the empiric nature of the combinations. One of the greatest challenges with standard BL therapy is toxicity, and although children and young adults can tolerate standard aggressive approaches, this is not the case with older or immunosuppressed adults. Although risk-adaptive therapy (ie, administering less toxic therapy to patients with lower-risk disease) has been somewhat helpful, there is a need to improve BL therapeutics and develop less toxic approaches while maintaining the high cure rates associated with standard regimens. The risks of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) and propensity for CNS dissemination in BL are also important therapeutic considerations when selecting up-front therapy. To reduce TLS, which can produce life-threatening renal failure and electrolyte imbalances, many regimens employ a pre-phase, whereby relatively low-dose cyclophosphamide and prednisone are administered. This strategy has been incorporated into the regimens of several groups. The high risk of CNS involvement is typically addressed by the use of high-dose intravenous methotrexate and cytarabine, both of which have CNS penetration, as well as intrathecal administration of these agents. An important advance over the years has been to eliminate whole-brain radiation for prophylaxis, which has significantly reduced CNS toxicity. Interestingly, a study published by the French, American, British/lymphomes malin B (FAB/LMB) demonstrated that patients with early stage BL had a high cure rate and low rate of CNS relapse without the use of intrathecal chemotherapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree