Central nervous system (CNS) relapse of aggressive B-cell lymphoma is a rare but serious complication with poor survival. Different approaches have been used to define risks factors for CNS relapse and establish prophylactic measures. Although patients with low or intermediate risk of CNS relapse should not undergo special diagnostic or therapeutic measures, CNS MRI as well as cytology and flow cytometry of the cerebrospinal fluid are suggested for high-risk patients (and patients with testicular involvement) at diagnosis, and prophylactic high-dose methotrexate in patients without proven CNS involvement. Future risk and treatment models may include molecular features and new treatment options.

Key points

- •

Central nervous system (CNS) relapse of aggressive B-cell lymphoma is a rare but serious complication with a short median survival.

- •

Different approaches have been used to define risks factors for CNS relapse and to establish efficient prophylactic measures.

- •

The CNS International Prognostic Index was established on patients treated in clinical trials of the German Aggressive non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) and in the Mabthera International Trial, and was validated on patients treated in British Columbia (British Columbia Cancer Agency).

- •

Although patients with low or intermediate risk of CNS relapse should not undergo special diagnostic or therapeutic measures, the authors suggest CNS MRI as well as cytology and flow cytometry of the cerebrospinal fluid for high-risk patients (and patients with testicular involvement) at diagnosis and to consider prophylactic high-dose methotrexate treatment of patients without proven CNS involvement.

- •

Future risk and treatment models may include molecular features (BCL2/MYK) and new treatment options like ibrutinib and lenalidomide.

Introduction

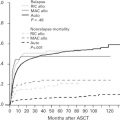

Secondary involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma is a serious complication with a median survival of only few months to less than 1 year. However, it is a rare event, with a recent meta-analysis of almost 5000 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or equivalent anthracycline-based chemotherapy showing a risk of CNS recurrence of only ≈5%. Thus, it is not rational to support prophylaxis in all patients. However, the risk is considerably greater in those with high-risk features at diagnosis, and identifying a high-risk group is key to guiding prophylactic strategies. In addition, the optimal type of CNS prophylaxis remains unknown. Intrathecal chemotherapy is commonly administered; however, most studies fail to show a protective effect ( Table 1 ); parenchymal relapse remains the predominant site in the rituximab era. Extrapolating from treatment paradigms in primary CNS lymphoma, high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX) has been explored for use in primary prophylaxis with encouraging results, but toxicities remain problematic and its use is restricted to younger patients. Further, systemic relapse also remains problematic in this high-risk group. This article reviews risk factors for CNS relapse with a focus on studies evaluating patients with DLBCL treated in the rituximab era as well as studies evaluating specific prophylaxis strategies. In addition, it discusses the role of further risk factors for CNS disease as well as the potential of novel therapies such as ibrutinib and lenalidomide in combination with R-CHOP.

| Study | Number of Patients | Systemic/IT Treatment | CNS Prophylaxis Indications | CNS Relapse (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmitz et al, 2012 | 2196 (1576 w/o R, 620 with R) | (R)-CHOEP a IT MTX | BM, testis, head, sinuses, orbits, oral cavity, tongue, and salivary glands | 2.6 (all pt) | .386 |

| Boehme et al, 2009 | 1222 (612 w/o R, 610 with R) | (R)-CHOP IT. MTX | BM, testis, head, sinuses, orbits, oral cavity, tongue, and salivary glands | 2.5 (w/o prophylaxis) 4.4 (with prophylaxis) | NS |

| Kumar et al, 2012 | 989 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT MTX ± IT Ara-C, IV MTX (28%) | At the discretion of investigator | 2.1 (w/o prophylaxis) 10.9 (with prophylaxis) | .007 |

| Tai et al, 2011 | 499 (179 w/o R, 320 with R) | (R)-CHOP IT. MTX | >1 ENS, orbits, sinuses, breast, testis, bone, BM | 5 (w/o prophylaxis) 11 (with prophylaxis) | NR |

| Tomita | 322 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT. MTX | ↑ LDH, bulk >10 cm, PS ≥2, BM, nasal, bone, breast, skin, testis | 2.8 (w/o prophylaxis) 7.5 (with prophylaxis) | .14 |

| Arkenau et al, 2007 | 259 (177 w/o R, 62 with R) | (R)-CHOP (R)-PmitCEBO IT. MTX ± Ara-C | BM, testis, sinuses, orbits, bone, blood | 1.1 (CI, 0%–2.5%) 2 pt w/o prophylaxis 1 pt with prophylaxis | NR |

| Guirguis et al, 2012 | 214 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT MTX (25 pt), IV MTX (17 pt) | ↑ LDH, >1 ENS, testis, epidural, sinuses, or skull | 2 (w/o prophylaxis) 1.9 (with prophylaxis) | NR |

a Includes patients treated with sequential high dose therapy and rituximab.

Introduction

Secondary involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma is a serious complication with a median survival of only few months to less than 1 year. However, it is a rare event, with a recent meta-analysis of almost 5000 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or equivalent anthracycline-based chemotherapy showing a risk of CNS recurrence of only ≈5%. Thus, it is not rational to support prophylaxis in all patients. However, the risk is considerably greater in those with high-risk features at diagnosis, and identifying a high-risk group is key to guiding prophylactic strategies. In addition, the optimal type of CNS prophylaxis remains unknown. Intrathecal chemotherapy is commonly administered; however, most studies fail to show a protective effect ( Table 1 ); parenchymal relapse remains the predominant site in the rituximab era. Extrapolating from treatment paradigms in primary CNS lymphoma, high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX) has been explored for use in primary prophylaxis with encouraging results, but toxicities remain problematic and its use is restricted to younger patients. Further, systemic relapse also remains problematic in this high-risk group. This article reviews risk factors for CNS relapse with a focus on studies evaluating patients with DLBCL treated in the rituximab era as well as studies evaluating specific prophylaxis strategies. In addition, it discusses the role of further risk factors for CNS disease as well as the potential of novel therapies such as ibrutinib and lenalidomide in combination with R-CHOP.

| Study | Number of Patients | Systemic/IT Treatment | CNS Prophylaxis Indications | CNS Relapse (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmitz et al, 2012 | 2196 (1576 w/o R, 620 with R) | (R)-CHOEP a IT MTX | BM, testis, head, sinuses, orbits, oral cavity, tongue, and salivary glands | 2.6 (all pt) | .386 |

| Boehme et al, 2009 | 1222 (612 w/o R, 610 with R) | (R)-CHOP IT. MTX | BM, testis, head, sinuses, orbits, oral cavity, tongue, and salivary glands | 2.5 (w/o prophylaxis) 4.4 (with prophylaxis) | NS |

| Kumar et al, 2012 | 989 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT MTX ± IT Ara-C, IV MTX (28%) | At the discretion of investigator | 2.1 (w/o prophylaxis) 10.9 (with prophylaxis) | .007 |

| Tai et al, 2011 | 499 (179 w/o R, 320 with R) | (R)-CHOP IT. MTX | >1 ENS, orbits, sinuses, breast, testis, bone, BM | 5 (w/o prophylaxis) 11 (with prophylaxis) | NR |

| Tomita | 322 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT. MTX | ↑ LDH, bulk >10 cm, PS ≥2, BM, nasal, bone, breast, skin, testis | 2.8 (w/o prophylaxis) 7.5 (with prophylaxis) | .14 |

| Arkenau et al, 2007 | 259 (177 w/o R, 62 with R) | (R)-CHOP (R)-PmitCEBO IT. MTX ± Ara-C | BM, testis, sinuses, orbits, bone, blood | 1.1 (CI, 0%–2.5%) 2 pt w/o prophylaxis 1 pt with prophylaxis | NR |

| Guirguis et al, 2012 | 214 (all with R) | R-CHOP IT MTX (25 pt), IV MTX (17 pt) | ↑ LDH, >1 ENS, testis, epidural, sinuses, or skull | 2 (w/o prophylaxis) 1.9 (with prophylaxis) | NR |

a Includes patients treated with sequential high dose therapy and rituximab.

Who: risk of central nervous system disease

There have been several studies evaluating potential risk factors for CNS recurrence in DLBCL. Originally, risk estimates were largely based on early experience of small studies from single institutions or cooperative groups. These series published decades ago do not reflect modern diagnostic and therapeutic standards and are now of limited value. In the last decade, there have been several studies evaluating the risk of CNS recurrence in patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP or an equivalent regimen either as post hoc analyses of prospective randomized studies or retrospective analyses performed on population-based cohorts of patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma, primarily DLBCL. Some of these studies compared the incidence and type of CNS disease in patients treated with R-CHOP or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP). Taken together, at best there has been a modest impact of rituximab on reducing the risk of CNS relapse. The RICOVER-60 trial evaluated 1112 patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma, primarily DLBCL (81.6%) and found that the 2-year incidence of CNS disease was 6.9% after CHOP14 (biweekly cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) and 4.1% after R-CHOP14 ( P = .046). A retrospective analysis from the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) found a similar trend in a higher risk population (3-year risk, 9.7% R-CHOP vs 6.4% CHOP; P = .085) and receiving rituximab was associated with a protective effect in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio = 0.045; P = .034); the impact of rituximab was more profound in patients in complete remission (3-year risk, 5.8% vs 2.2%; P = .009), suggesting that the predominant impact is in systemic disease control with secondary reduction in CNS disease. In 2016, only studies in patients treated with R-CHOP or combinations of rituximab with alternative chemotherapy regimens reflect current standard of care.

Before summarizing and discussing the key findings of recent studies investigating the risk of secondary CNS disease it is important to note the degree of heterogeneity across studies with regard to the definition of high-risk patients, CNS-directed diagnostic investigations used, and recommendations and type of CNS prophylaxis incorporated into first-line treatment. These differences may affect the proportion of patients diagnosed with CNS relapse and the identification of risk factors, and may also affect the evaluation of CNS prophylaxis.

Most importantly, proposals for future strategies (ie, who, what, and at which time) should take into account that the availability and more strict implementation of state-of-the-art diagnostic approaches like brain MRI and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) detect CNS disease at diagnosis in a greater but unknown proportion of patients who previously went undetected, leaving behind a remnant CNS-negative population with a risk of CNS disease that will be overestimated by applying current risk models. The dynamics of CNS relapse imply that a substantial proportion of patients already harbor lymphoma in the CNS at the time of diagnosis, rather than developing de novo CNS involvement after a remission in other compartments has been achieved.

Another limitation is that most information on CNS disease is restricted to patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP and may not apply to other aggressive B-cell lymphomas or alternative treatment regimens. For instance, the (R)-ACVBP (adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, prednisolone) regimen used in International Prognostic Index (IPI) high-intermediate or high-risk DLBCL is combined with an intensive consolidation phase including intravenous (IV) methotrexate (MTX), etoposide, ifosfamide, and cytosine-arabinoside. These drugs, all of which cross the BBB, likely contribute to the low frequency of CNS disease (<1%) seen in patients treated with this regimen even before rituximab was introduced into first-line therapy for DLBCL. Studies using the (R)-ACVBP regimen therefore should not be used to define risk groups or prophylactic strategies for patients treated with the standard R-CHOP regimen. Whether rates of CNS recurrences seen in patients treated with R-CHOEP or DA-EPOCH-R differ from those observed in R-CHOP–treated patients is unknown. The phase 3 study comparing DA-EPOCH-R with R-CHOP ( ClinicalTrial.gov number NCT00118209 ) has been completed and the results are eagerly awaited, including impact on the risk of CNS relapse. Etoposide crosses the BBB and earlier studies without rituximab showed that the addition of etoposide reduced the frequency of CNS relapse ; however, with the addition of rituximab, the effect is no longer apparent.

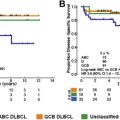

For reasons mentioned earlier, this article focuses on risk factor analyses and prophylactic strategies reported for patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP. Patients with rare subtypes of DLBCL (primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type; Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL of the elderly; intravascular large B-cell lymphoma) or patients who are HIV positive may have different (higher) incidences of CNS relapse. Table 2 summarizes risk factors for CNS relapse found in larger studies (>200 patients) of patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Some of these studies compared R-CHOP or CHOP ; for these studies, only patients treated with R-CHOP and the risk factors identified in R-CHOP–treated patients by multivariate analysis are reported. Altogether, the data confirm that secondary CNS involvement is a fairly rare complication of DLBCL, occurring in 2.3% to 8.4% of patients analyzed (with 2-year rates of 2.8%–4.8%). The overall variation in frequencies of CNS disease reported by different investigators reflects the differing patient populations studied and possibly prophylactic strategies used. Identified risk factors include the individual IPI risk factors (age >60 years, high lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] level, poor performance status, advanced stage, and >1 extranodal site). In addition, involvement of kidney, adrenals, female reproductive organs, testis, and bone have been reported to increase the risk of CNS disease. Bone marrow involvement has also been reported to be associated with increased risk of CNS recurrence, although studies do not always specify whether it is caused by involvement of DLBCL. In the largest study published so far, including 2164 patients treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOE(etoposide)P, of prospective trials conducted by the German High-grade Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL), a CNS risk model was developed, including all five IPI-factors and kidneys/adrenals (CNS-IPI). Patients were stratified as low risk (0, 1 factors), intermediate risk (2, 3 factors), or high risk (≥4 factors). Notably, the 12% of patients forming the high-risk group had a 2-year-rate of CNS disease of ≈10% ( Table 3 ). This clinical risk model has been validated in an independent data set of 1597 patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP from the BCCA ( Fig. 1 ). Meanwhile, other studies of PET-staged patients with DLBCL also applied this model and confirmed its validity (Gleeson and colleagues, personal communication, 2016). Although the CNS-IPI is a robust, reproducible model and serves as a useful benchmark to evaluate other risk factors, including biomarkers, a very-high-risk group was not identified.

| Study | Patients b | IPI | ↑ LDH c | >1 ENS | Advanced Stage | Extranodal Site | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmitz et al | 64 out of 2164 (3.0%) | S | S | NS | S | Kidney/adrenal | 2.8 | — |

| Skin | 7.5 | |||||||

| Savage et al, 2014 | 71 out of 1597 (4.4%) | S | S | S | S | Kidney/adrenal | 2.9 | — |

| Marrow | 1.7 | |||||||

| Testis | 6.6 | |||||||

| Tomita et al | 82 out of 1221 (6.7%) | NS | NS | NS | NS | Breast | 10.5 | Aged >60 y, 2.1 |

| Adrenal | 4.6 | |||||||

| Bone | 2.0 | |||||||

| Schmitz et al, 2012 | 14 out of 620 (2.3%) | Not applicable | 3.8 | NS | 5.4 | NS | R 0.3, not in high-risk patients | |

| Boehme et al | 22 out of 608 (3.6%) | NR | S | S | NS | NR | ECOG scale >1 | |

| Tai et al | 19 out of 320 (6.0%) | NS | NS | NS | NS | Kidney | 20.1 | ECOG scale >1, 2.0 Non-CR, 3.3 |

| Testis | 6.7 | |||||||

| Breast | 6.1 | |||||||

| Villa et al | 19 out of 309 (6.1%) | NS | NS | NS | Stage IV 8.0 | Kidney | 3.3 | — |

| Shimazu et al | 20 out of 238 (8.4%) | NR | 2.4 | 2.0 | NS | Marrow | 2.1 | Aged >60 y, 2.5 |

| Guirguis et al | 8 out of 214 (3.7%) | NS | NS | NS | NS | Testis | 33.5 | None |

| Yamamoto et al | 81 out of 203 (3.9%) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | — | |

| Chihara et al | 9 out of 203 (4.4%) | NS | NS | Any EN 2.9 | NS | NS | Bulk >7.5 cm, 3.34 ALC <1.0 × 10 9 /L, 2.38 | |

| Feugier et al | 11 out of 202 (5.4%) | S | S | NS | NS | NS | ECOG scale, >1 | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree