Second-line therapy options for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that is refractory to, or relapses after, current rituximab-containing primary therapy continue to evolve. For younger patients, salvage therapy followed by intensive therapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) remains the treatment of choice for those with chemotherapy-sensitive disease. Combination therapy may be used for those who are not candidates for ASCT. In contrast, patients with DLBCL refractory to 2 lines of therapy have a very poor prognosis and generally short survival, and should be carefully considered for participation in clinical trials of novel approaches.

Key points

- •

Although the addition of rituximab to primary chemotherapy has reduced the incidence of primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the outcome of such patients remains very poor.

- •

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) remain standard for patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL after rituximab-containing primary chemotherapy.

- •

Patients older than 60 years benefit from attempts at salvage therapy; data in patients older than 70 years are more limited.

- •

Current evidence suggests that rituximab should be included with second-line therapy.

- •

For those relapsing after, or who are not eligible for, ASCT, median survival is 6 to 8 months, and eligible patients should be enrolled in clinical trials of new agents for DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of B-cell lymphoma in North America, representing 30% of all lymphomas in adults. The incidence of this lymphoma increases with age, and, in North America, median age at diagnosis is approximately 65 years. Although overall survival (OS) has improved with the addition of the CD20 antibody rituximab to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy, treatment failure still occurs in a significant proportion of patients with limited stage disease at presentation, and up to half of patients with advanced stage disease. With a median follow-up of 10 years, results from the GELA (Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte) randomized trial showed that 40% of patients in the R-CHOP arm developed progressive disease: more than 80% of progression events occurred within the first 3 years after treatment, 10% occurred within years 4 and 5, and 10% after 5 years. Ongoing recurrence risk is much lower in patients with stage I and II disease, but late recurrences do occur. Some late recurrences may represent reemergence of an indolent lymphoma histology, emphasizing the need for biopsy of all such patients before the initiation of therapy. In a series of patients with recurrence of lymphoma more than 5 years from completion of therapy (median time to relapse 7.4 years, range 5–20 years), two-thirds had stage I/II disease at diagnosis and more than 80% had low-risk International Prognostic Factors Index (IPI). Assessment of cell of origin according to the Hans algorithm showed that such recurrences have a germinal center B-cell immunophenotype, and have other characteristics of germinal center B cells.

What is the expected outcome of patients who progress or relapse after initial treatment? In the pre-rituximab era, despite the availability of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), median survival after progression or relapse for patients treated with CHOP or equivalent combination regimens was only 9 months, and 2-year survival was 30%. In more than 3000 patients with aggressive lymphoma treated on GELA trials over the last 20 years, OS of patients with primary refractory lymphoma was 12% at 7 years; those with late relapse more than 1 year after therapy had 7-year OS of 38%. Among the patients with late relapse more than 5 years after primary therapy reported by Larouche and colleagues, 5-year event-free survival from relapse was only 17% and OS 27%, suggesting that late relapse did not portend a good prognosis. Event-free survival seemed to be better for patients who underwent intensive therapy with ASCT compared with standard-dose treatments (56% vs 18%), although patient selection and inclusion of those refractory to salvage chemotherapy in the standard-dose therapy group likely account for some of this apparent difference.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of B-cell lymphoma in North America, representing 30% of all lymphomas in adults. The incidence of this lymphoma increases with age, and, in North America, median age at diagnosis is approximately 65 years. Although overall survival (OS) has improved with the addition of the CD20 antibody rituximab to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy, treatment failure still occurs in a significant proportion of patients with limited stage disease at presentation, and up to half of patients with advanced stage disease. With a median follow-up of 10 years, results from the GELA (Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte) randomized trial showed that 40% of patients in the R-CHOP arm developed progressive disease: more than 80% of progression events occurred within the first 3 years after treatment, 10% occurred within years 4 and 5, and 10% after 5 years. Ongoing recurrence risk is much lower in patients with stage I and II disease, but late recurrences do occur. Some late recurrences may represent reemergence of an indolent lymphoma histology, emphasizing the need for biopsy of all such patients before the initiation of therapy. In a series of patients with recurrence of lymphoma more than 5 years from completion of therapy (median time to relapse 7.4 years, range 5–20 years), two-thirds had stage I/II disease at diagnosis and more than 80% had low-risk International Prognostic Factors Index (IPI). Assessment of cell of origin according to the Hans algorithm showed that such recurrences have a germinal center B-cell immunophenotype, and have other characteristics of germinal center B cells.

What is the expected outcome of patients who progress or relapse after initial treatment? In the pre-rituximab era, despite the availability of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), median survival after progression or relapse for patients treated with CHOP or equivalent combination regimens was only 9 months, and 2-year survival was 30%. In more than 3000 patients with aggressive lymphoma treated on GELA trials over the last 20 years, OS of patients with primary refractory lymphoma was 12% at 7 years; those with late relapse more than 1 year after therapy had 7-year OS of 38%. Among the patients with late relapse more than 5 years after primary therapy reported by Larouche and colleagues, 5-year event-free survival from relapse was only 17% and OS 27%, suggesting that late relapse did not portend a good prognosis. Event-free survival seemed to be better for patients who underwent intensive therapy with ASCT compared with standard-dose treatments (56% vs 18%), although patient selection and inclusion of those refractory to salvage chemotherapy in the standard-dose therapy group likely account for some of this apparent difference.

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Although understanding of the diverse biology of DLBCL has evolved, and patient subsets defined by molecular profiles such as cell of origin may start to guide therapy at the time of diagnosis and at relapse, high-dose chemotherapy with ASCT support is still regarded as the standard of care for eligible patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL. The randomized trial reported by Phillip and colleagues in 1995 forms the basis of this recommendation even now. To be eligible for the Parma trial, all patients had a complete response (CR) to prior anthracycline-containing induction treatment, and patients with central nervous system (CNS) or bone marrow involvement at the time of relapse were excluded. Salvage therapy consisted of dexamethasone, cisplatin, and cytarabine (DHAP) and bone marrow was the source of stem cells, harvested following 1 course of DHAP. Patients with a CR or partial response (PR) after 2 cycles of DHAP were randomized to continuation with DHAP for 4 cycles or high-dose chemotherapy with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and cyclophosphamide (BEAC). Radiotherapy was indicated in both arms for bulky disease larger than 5 cm at the time of relapse, using involved field radiation according to Ann Arbor staging. For patients in the high-dose therapy arm, the total dose of radiation was 26 Gy given twice daily before transplant, whereas in the standard arm radiation was 35 Gy in 20 fractions given following completion of DHAP.

Patients undergoing ASCT for DLBCL now differ from those enrolled in this small trial reported 20 years ago: patients in the Parma trial all had a CR to first-line therapy, and were less than or equal to 60 years of age at randomization; none had transformed lymphoma, and no patient had received the CD20 antibody rituximab. Patients currently considered for salvage chemotherapy with curative intent are up to age 70 years or older, may have relapsed with CNS involvement, may have primary refractory disease, and have been treated with chemoimmunotherapy including rituximab. Although the treatment environment is currently different, other lessons from this trial remain important, including the influence of disease biology on treatment outcome: patients with higher number of IPI risk factors at relapse, and those with remission less than 1 year, derive less benefit from attempts at salvage therapy and ASCT, and these factors have been used to stratify patients in recent randomized trials of salvage therapy. Tissue biomarkers for response to salvage therapy and ultimate outcome of stem cell transplant have been evaluated in the context of single-center reports and the randomized CORAL (collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma) trial, suggesting that further evaluation of results according to cell of origin or presence of high-risk cytogenetic changes such as CMYC translocation are warranted. At present, tissue biomarkers have not identified a population of patients who have an excellent prognosis, wherein omission of ASCT from second-line therapy could be considered, or a subgroup destined to receive no benefit from aggressive salvage therapy. The specific application of intensive therapy to patients with transformed lymphoma or those with dual translocation (double-hit) DLBCL are discussed elsewhere.

Choice of salvage therapy before autologous stem cell transplant

Recent randomized trials have explored essential questions in the application of high-dose therapy for relapsed or refractory DLBCL ( Table 1 ). An important study by the HOVON (Dutch-Belgium cooperative trial group) showed that the addition of rituximab to salvage chemotherapy for relapsed DLBCL expressing CD20 resulted in significant improvement in response rate (75% vs 54%), failure-free survival at 24 months (50% vs 24%), and progression-free survival (PFS; 52% vs 31%). Cox analysis adjusted for duration of first remission, performance status, and relapse IPI showed an improvement in OS at 24 months favoring the addition of rituximab; most importantly, most patients enrolled in this trial were rituximab naive.

| N | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| CD20 Antibody | ||

| DHAP/VIM/DHAP ± rituximab | 239 | RR: R-chemo, 74%; chemo, 54% PFS: R-chemo, 52%; chemo, 31% |

| Rituximab + DHAP vs ofatumumab + DHAP | 447 | RR: ofatumumab, 38%; R, 42% 2-y PFS: ofatumumab, 21%; R, 28% 2-y OS: ofatumumab, 41%; R, 36% |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| R-ICE vs R-DHAP | 477 | CR/CRu R-ICE, 36%; R-DHAP, 40% RR R-ICE, 63%; R-DHAP, R-ICE, 64% 3-y PFS, 31% vs 42% 3-y OS, 47% vs 51% |

| GDP vs DHAP | 619 | CR/CRu GDP, 13.5% vs DHAP, 14.3% RR GDP, 45.1% vs DHAP, 44.1% 4-y EFS, 26% vs 28% 4-y OS, 39% vs 39% |

Two randomized trials have addressed choice of the optimum salvage chemotherapy before ASCT. The CORAL trial conducted by Gisselbrecht and colleagues compared ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide plus rituximab (R-ICE) with DHAP plus rituximab (R-DHAP). The primary end point of this superiority trial was mobilization-adjusted response rate after 3 cycles of chemotherapy (considering patients whose stem cell mobilization failed to achieve the target of 2 × 10 6 CD34 cells/kg as having experienced treatment failure, regardless of response). This trial showed a similar CR rate for R-ICE versus R-DHAP (36% vs 40%), overall response rate (63% vs 64%) and mobilization-adjusted response (52% vs 54%); ASCT with BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) was performed in 51% of patients receiving R-ICE and 55% of patients receiving R-DHAP. Event-free survival and PFS were similar between the two induction regimens. The NCIC-CTG study LY.12 compared gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin (GDP) with DHAP in a noninferiority design; secondary end point was stem cell mobilization rate. Rituximab was added to both chemotherapy arms for patients with CD20+ lymphoma part way through this study, through protocol amendment. This study was positive, reaching its noninferiority threshold of a difference between the study arms of less than 10%: overall response rate (CR/complete response unconfirmed (CRu), PR) following 2 cycles of GDP was 45%, compared with 44.1% for DHAP. Transplantation rates were also similar between the two study arms: GDP 51.0%, DHAP 48.9%. PFS and OS at 4 years were not different between the two arms. However, DHAP chemotherapy produced significantly greater acute toxicity and need for hospitalization to manage adverse events, and GDP represents a highly cost-effective alternative to DHAP.

In an effort to improve results of salvage therapy, alternative antibodies to rituximab have been tested. Matasar and colleagues reported a phase II trial of the addition of the fully human monoclonal CD20 antibody ofatumumab to ICE or DHAP chemotherapy before ASCT, with an overall response in patients with refractory disease or early relapse of 55% and CR rate of 30%. However, in a randomized comparison of ofatumumab with rituximab in combination with the same salvage therapy, no differences in response rate or PFS were observed.

Conditioning regimens for autologous stem cell transplant for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

The rationale for ASCT is to use high doses of chemotherapy to overcome drug resistance, and several regimens have historically been used based on institutional experience. There are no prospective randomized comparisons of the chemotherapy components of the high-dose therapy regimens with stem cell support for aggressive lymphomas. The impact of conditioning regimen on outcome with ASCT for lymphomas was recently reported by collaborators at the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, including 1837 patients treated with ASCT for DLBCL. The key outcomes of this large registry analysis are shown in Table 2 . There were differences observed among the most commonly used intensive therapy regimens in recipient age, duration of follow-up, and prior rituximab exposure; age-adjusted IPI was similar across the cohorts. The choice of regimen had no independent influence on treatment-related mortality (TRM), which was higher patients who were older, had worse performance status, had chemotherapy-resistant disease, and had a larger number of prior therapy regimens. The incidence of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS), an important cause of transplant-related morbidity and mortality, at 1 year ranged from 3% to 6% and was related to carmustine (BCNU) doses more than 300 mg/m 2 , age, and chemotherapy-resistant disease; patients who experienced IPS had higher TRM. In this analysis, for patients with DLBCL undergoing ASCT with high-dose cyclophosphamide carmustine etoposide (CBV), relapse rate was similar to other high-dose regimens but overall mortality was higher, and the use of this regimen is not recommended.

| Outcome at 3 y | BEAM N = 731 | CBV LOW N = 465 | CBV HIGH N = 187 | BU-CY N = 273 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse/Progression (%) | 44 (40–47) | 40 (36–45) | 46 (40–54) | 41 (35–47) |

| PFS (%) | 47 (44–51) | 47 (43–52) | 39 (32–44) | 45 (39–52) |

| OS (%) | 58 (55–62) | 55 (50–59) | 43 (35–51) | 52 (46–58) |

| 1-y Treatment-related Mortality (%) | 4 (3–5) | 7 (5–8) | 8 (6–11) | 7 (6–9) |

In order to improve the efficacy of the BEAM regimen, trials of the addition of a radioimmunoconjugate to high-dose chemotherapy have been performed, with encouraging results. The Bone Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network performed a randomized phase III trial comparing BEAM combined with rituximab or with 131 I tositumomab in patients with chemotherapy-sensitive DLBCL. Patients with persistent (PR to initial therapy) or relapsed DLBCL were included: after a median follow-up of 25 months, PFS was 48.6% for patients receiving rituximab-BEAM and 47.9% for patients receiving 131 I tositumomab-BEAM, with no difference in OS. Time to neutrophil recovery and platelet transfusion independence were similar between the 2 high-dose treatments; grade 3 or greater mucositis was the only significant toxicity that was more frequent in the tositumomab arm. Day 100 transplant-related mortality was also similar in both arms (4.1% vs 4.9%).

The problem of primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Failure to achieve at least a PR following initial chemotherapy, or progression within 3 months of treatment completion, have been used to define primary refractory DLBCL. Although the addition of rituximab has reduced the incidence of this from between 10% and 20% to between 5% and 10% in trials of up-front therapy, the outcome of this patient population remains poor. Several studies suggest that this population may be enriched with lymphoma bearing molecular features such as dual expression of BCL2 and CMYC protein and presence of cmyc translocation, alone or with bcl2 or bcl6 translocation (double-hit lymphoma). The response rate to salvage therapy in patients with primary refractory DLBCL who are potentially eligible for ASCT is significantly lower than for those who experience relapse after achieving complete remission. Although patients with primary refractory DLBCL may still be considered for ASCT, the limitations of current salvage therapy regimens in this patient population need to be acknowledged in discussions of treatment options and outcomes, and enrollment of such patients in clinical trials of novel salvage therapy approaches is encouraged.

Patients with relapsed or primary refractory DLBCL whose lymphoma does not respond to initial salvage treatment (refractory relapse) represent an additional therapeutic challenge. Although many centers routinely offer second-line salvage (third-line chemotherapy) to this patient population, the proportion of patients who are able to proceed to ASCT is small. Seshadri and colleagues evaluated 120 patients with DLBCL who had no response to or progression after cisplatin-containing salvage treatment before intended ASCT; the response rate to a second salvage regimen was 14% (10 out of 71; 1 CR, 9 partial PRs) and only 1 of 43 patients who were primary refractory to CHOP responded to third-line therapy. In this series, only 8 of 71 patients receiving second-line salvage therapy were able to proceed to ASCT, with PFS at 2 years of 31%. In an analysis of patients in the CORAL trial who did not proceed to ASCT because of treatment failure after initial salvage with R-ICE or R-DHAP, the response rate to second salvage for those with stable or progressive disease was 32% (43 out of 135), and 44 patients ultimately underwent autologous (n = 37) or allogeneic (n = 7) transplant. Median survival for those undergoing transplant was 10.6 months, and 2-year OS was 34%; PFS for this group of patients was not reported. Patients with low-risk IPI scores and who are not refractory to primary therapy may benefit from a second salvage attempt, but the probability of undergoing ASCT and long-term PFS are very low in this population.

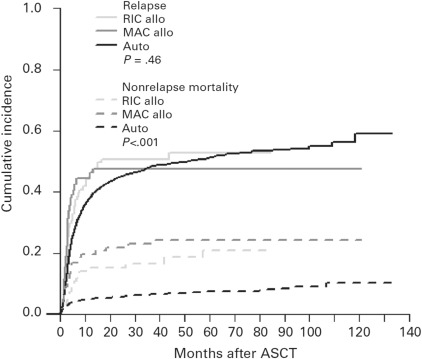

There are currently no data to support the notion that patients with primary refractory DLBCL derive greater benefit from matched related or unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplant compared with ASCT. A recent report from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Lymphoma Working Party showed that 4-year non-relapse mortality is significantly higher for patients receiving allogeneic transplant (either myeloablative or reduced-intensity conditioning), and 4-year PFS and OS were superior for patients undergoing ASCT for relapsed or refractory DLBCL. After adjusting for baseline factors (including chemotherapy-resistant lymphoma, which was more common in patients receiving an allotransplant), relapse incidence was not different between patients undergoing ASCT or allogeneic transplant, although mortality was significantly worse for patients receiving an allogeneic transplant ( Fig. 1 ). PFS at 4 years for patients with chemorefractory disease was 23% for ASCT, 20% for myeloablative allotransplant, and 4% for reduced-intensity allotransplant.

Central nervous system recurrence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Relapse or progression in the CNS is an uncommon but generally fatal event in patients with DLBCL. There is considerable controversy over the population of patients who are at increased risk of CNS relapse, and the benefit of prophylactic therapies such as intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy or high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) in reducing the rate of relapse in the CNS. In the pre-rituximab era, most CNS progression occurred during or within 3 months of completion of systemic therapy. Data from trials evaluating the addition of rituximab to CHOP suggest that CNS progression may be an early event in younger patients with high-intermediate or high IPI score at presentation, and the addition of rituximab has done little to reduce this risk. In older patients, addition of rituximab has reduced the risk of CNS progression, although IPI at the time of diagnosis remains the most relevant risk factor for relapse in the CNS. Risk of treatment failure in the CNS is very low in patients with low IPI regardless of age: the 2-year rate of CNS failure in the recent Cancer Research UK comparison of R-CHOP-21 with R-CHOP-14 was less than 1%. Although specific sites of extranodal involvement have generally not been reliable predictors of CNS relapse, it has been reported that CNS involvement at diagnosis and as a site of relapse is more common in patients with dual translocation or dual protein expression DLBCL, as discussed elsewhere.

CNS recurrence of DLBCL portends a poor prognosis, with median survival ranging from 2 to 7 months. Patients with isolated parenchymal brain recurrence after induction therapy may represent a unique patient subgroup with regard to treatment options and outcomes. In one retrospective analysis of 113 patients (83% DLBCL), the median time to recurrence was 1.8 years, and following CNS-directed therapy with HD-MTX, whole-brain radiotherapy or both, median PFS was 1.0 years, with 23% of patients alive at 3 years. PFS and OS seemed to be better with the use of HD-MTX compared with whole-brain irradiation, although most second progression events still occurred in the CNS. These results must be interpreted cautiously, because considerable selection bias may underlie the choice of treatments received in this patient cohort collected from a large number of centers; specifically, the ability to administered HD-MTX versus whole-brain irradiation. HD-MTX is a reasonable treatment option for fit patients with good performance status and normal renal function. For most patients, whole-brain irradiation represents an important palliative treatment option, with an overall response rate of 67% and median survival of 8.6 months reported by Khimawi and colleagues with 40-Gy whole-brain radiotherapy.

Earlier reports highlighted the poor outcome of patients with CNS involvement undergoing ASCT with CNS involvement, compared with patients with systemic relapse alone. However, recent case series have suggested that long-term survival may be achieved in selected patients undergoing intensive therapy and ASCT. A recent international retrospective collaboration reported that patients treated with ASCT (most commonly using thiotepa and carmustine) had improved 3-year survival compared with those not receiving intensive therapy (42% vs 14%). It is likely that patient selection is partly responsible for these improved results, because the cohort reported was younger overall (median age 58 years) than expected for patients with DLBCL, and those undergoing ASCT had better performance status and chemotherapy-sensitive disease, compared with those not transplanted.

However, prospective trials of ASCT have recently been reported, supporting the observation from retrospective series that some patients with secondary CNS lymphoma may benefit from this approach. Korfel and colleagues evaluated induction treatment in 30 patients (6 with systemic involvement at study entry) with 2 cycles of HD-MTX and ifosfamide and IT liposomal ara-C, followed by high-dose cytarabine and thiotepa for stem cell mobilization. Twenty patients had a CR or PR to induction treatment and 24 proceeded to high-dose therapy with carmustine, thiotepa, and etoposide. Two-year time to treatment failure (TTF) was 49% for the whole cohort and 58% for those undergoing ASCT; OS at 2 years was 63%. Thirteen of 16 patients with treatment failure had CNS progression.

Ferrari and colleagues reported a phase II multicenter study of high-dose sequential therapy in 38 patients with secondary CNS involvement with (n = 23) or without (n = 15) concomitant systemic lymphoma. Induction therapy consisted of rituximab with HD-MTX, cytarabine, and IT liposomal ara-C; responding patients had stem cell mobilization with ara-C or MTX, followed by additional therapy for those with systemic DLBCL. Twenty patients underwent intensive therapy with carmustine and thiotepa followed by ASCT. The CR rate to all therapy was 20 out of 38; event-free survival at 5 years was 40%, with events including progressive disease (PD) in 10 patients, relapse from CR in 7, and toxic death in 4 patients. Thirteen patients experienced relapse or progression in the CNS.

Intensive therapy and ASCT are appropriate therapy for patients with CNS relapse, with or without systemic recurrence, following response to CNS-directed therapy; high-dose therapy regimens containing agents that cross the blood-brain barrier, such as thiotepa and carmustine (with or without etoposide), seem to produce the best results. Regimen-related toxicity is significant but manageable with these approaches, and long-term follow-up of neurocognitive function in survivors is needed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree