Unusual Tumors in Children

Some unusual and rare childhood tumors are comparable to those that occur in the adult population and require the same therapeutic strategy, with particular attention given to late sequelae. Some of these tumors are more characteristic of children and require specific radiotherapeutic strategies.

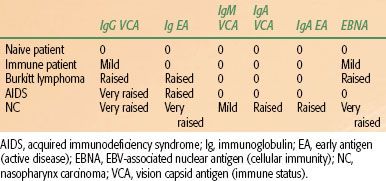

TABLE 90.1 ANTIGEN AND ANTIBODY EPSTEIN–BARR VIRUS TITERS

NASOPHARYNGEAL CARCINOMA IN CHILDHOOD

NASOPHARYNGEAL CARCINOMA IN CHILDHOOD

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a rare malignant tumor in childhood and adolescence (<1% of pediatric malignancies). The frequency differs greatly by geographic area: 1 case per 100,000 in Europe, the United States, and Australia; 10 per 100,000 in North Africa; and 80 per 100,000 in South China, Malaysia, and Greenland. According to the World Health Organization, there are three distinct classification groups: type I, keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma; type II, nonkeratinizing carcinoma; and type III, undifferentiated carcinoma. Most pediatric NPC cases are type III.1 As in older patients, Epstein–Barr virus is associated with this type of NPC. The virus is found in the tumoral cells and not in the surrounding lymphocytes. Antibody and antigen titers are useful for both diagnosis and follow-up (Table 90.1).2 The association between dietary factors and NPC has been suspected in China and seems to be confirmed in the last case–control study published by Jia et al.3

Clinical Presentation

The mean age at presentation is 14 years; boys are more often affected than girls.4 The tumor usually originates in the fossa of Rosenmuller, followed early on by locoregional extension, including extensive pharyngeal involvement and often bone, lung, and cervical lymph node metastases. The most frequent clinical symptoms are nasal obstruction, epistaxis, otitis, and neck and facial pain.

On clinical examination, bilateral lymphadenopathy and cranial nerve palsies are found; a nasopharyngeal mass can be seen by direct or indirect nasopharyngoscopy, and sometimes a protruding mass can be seen in the oral cavity.

The diagnostic workup must include a cranial and neck computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a thorax CT scan, and bone scintigraphy. Pathologic confirmation is obtained by biopsy. Commonly used staging systems are the TNM/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJC), Kyoto, and Ho classifications. The Ho and Kyoto systems are based on topographic extension; the more commonly used TNM/AJC classification is based on tumor volume and CT information.5

Treatment

In adult NPC, concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy (cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil) is the standard of care.6,7 Because of the scarcity of pediatric NPC cases, it is not feasible to perform randomized studies in this age group. Based on adult trials, multimodality treatment is generally accepted as standard of care for children. Usually two courses of 5-fluorouracil/cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (cisplatin) are given on weeks 1 and 5 of radiotherapy.8 Others have used neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy, followed by radiation.9

Radiation Therapy

A dose–response relationship for local control with a threshold at 60 Gy has been reported in a number of series.4,8,10 However, more recently Habrand et al.11 reported interesting results with lower doses of radiation therapy (50 Gy) in patients with good response to chemotherapy. These results are in accordance with the reports of Polychronopoulou et al.12 and Orbach et al.13 In this series, 70% of children achieved local control with doses of <60 Gy (50% received only 52 Gy). A recent study from St. Jude also reported a better outcome for patients receiving cisplatin and dose of radiotherapy >50 Gy.14 Techniques include CT for dosimetric purposes, three-dimensional (3D) dosimetry, customized blocking, and, if possible, MRI/CT scan image fusion for intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Proton beam therapy is appropriate where available.

The target volume encompasses the tumor site and the neck (even in N0 disease) due to the severity of late sequelae after standard techniques. The standard of care for radiotherapy is IMRT, if available.15 High–dose-rate, pulsed low–dose-rate, or conventional low–dose-rate intraluminal brachytherapy is used for the boost at some institutions. For some physicians, hyperfractionated radiotherapy is believed to be standard of care. A recent publication concerning hyperfractionated radiotherapy shows an increased rate of neurologic complication.16 The overall survival for T1-T2 disease is 70% to 90%. The survival for T3-T4 disease using combined modality is 50% to 60%. For advanced stage, innovative targeted therapies are in the development process. These include induction of the lytic viral cycle with ganciclovir, gene therapy, or antitumor vaccination against the viral protein LMP2.17,18

Late Effects

Xerostomia is the main side effect of treatment, followed by dental caries, trismus, muscular atrophy, nerve palsies, and endocrine dysfunction resulting from pituitary irradiation. Significant auditory late toxicity and sporadic cases of visual morbidity, secondary to radiotherapy with or without cisplatin-based chemotherapy have been reported.19 The St. Jude retrospective analysis reported a rate of 8.5% of subsequent malignancies 8.6 to 27 years after treatment.14

New techniques such as IMRT or radioprotective drugs such as amifostine may be able to decrease late sequelae.

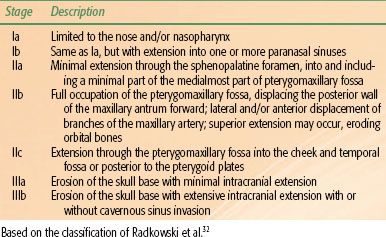

TABLE 90.2 STAGING CLASSIFICATION FOR JUVENILE NASOPHARYNGEAL ANGIOFIBROMA

OTHER HEAD AND NECK TUMORS

OTHER HEAD AND NECK TUMORS

Carcinoma of the Oropharynx and Salivary Glands

Schwaab et al.20 reported the largest pediatric series, with only 2% squamous cell carcinoma among 380 head and neck tumors. The more frequent sites of disease are the tongue, lip, tonsil palate, and salivary glands. Cigarette smoking or use of smokeless tobacco have been shown to be the etiologic factors for adolescent tongue carcinoma.21 For other sites, passive smoking, poor oral hygiene, or genetic predispositions (xeroderma pigmentosum or retinoblastoma) have been suggested.

Special attention must be paid to larynx carcinoma because some of the cases may develop from juvenile papillomatisis, a benign condition of the aerodigestive tract that may undergo malignant degeneration. Guidelines for surgery and radiation therapy are the same as those for adults. Combined chemotherapy and radiation can be attempted for organ conservation.22 The node area to treat does not differ from adults and must follow the Gregoire definition.23

Psychological support and rehabilitation programs are an essential part of the comprehensive treatment for children who undergo major surgical resection.

Esthesioneuroblastoma

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a malignant tumor arising from the olfactory nerve in the upper nasal cavity. Intracranial extension is common at the time of diagnosis. Esthesioneuroblastoma is mostly seen in patients in their 20s or 60s. Positive S-100 and neuron-specific enolase stains combined with negative epithelial markers strongly suggest a neurogenic origin.24 The clinical presentation includes nasal obstruction, loss of smell, epistaxis, and, sometimes, enlarged cervical lymph nodes. Bony structures are often involved, as well as the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses. The most commonly used staging/grouping system is by Kadish et al.24 and is based on degree of local tumor extension.

Standard treatment has not yet been defined. Localized tumors are often treated by surgery alone, but local relapse is very frequent. Therefore, postoperative radiotherapy is often proposed. In patients treated by combined surgery and irradiation, local control can be obtained in >75% of cases.25 Eich et al.26 and Broich et al.27 recommend combined surgery and radiotherapy in all stages. Demiroz et al.28 reviewed 26 patients treated between 1995 and 2007. The relapse rate for patients treated with surgery alone was 29% versus 0% for those treated by surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. The recommended dose is 50 to 60 Gy. Elective neck irradiation or dissection is not advocated because <10% of early-stage cases exhibit nodal involvement. However, node metastases are frequent if the tumor extends beyond the paranasal sinuses. In this case, lymph node dissection or prophylactic irradiation should be considered. Chemotherapy has not yet been accepted as part of routine first-line treatment, although responses to chemotherapy have been reported.29 Chemotherapy can be employed to reduce tumor volume prior to surgery or radiotherapy, as well as for palliative purposes in advanced cases. Promising results with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, cis-platinum, and etoposide, combined with radiotherapy and stem cell support, have been reported recently by Mishima et al.30 They obtained 8 complete responses in 12 Kadish stage C and D patients. Neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy as preoperative treatment for locally advanced esthesioneuroblastoma has been reported by Sohrabi et al.31 with very promising results.

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a malignant vascular tumor most often arising from the posterior lateral wall of the nasopharynx. The lesion tends to extend into the nasal cavities, maxillary and sphenoid sinuses, orbit, and infratemporal fossa. Several classifications have been proposed, but the classification of Radkowski et al.32 appears to be the most appropriate, at least for the surgical purposes (Table 90.2). Common symptoms are epistaxis, cheek swelling, a visible orbital tumor, and cranial nerve palsies. JNA is more frequent in familial adenomatous polyposis patients. A mutation in the cluster region of the APC gene was reported in several studies, suggesting that JNA is perhaps a familial adenomatous polyposis tumor.33,34

Treatment consists of surgery for small lesions, often with preoperative embolization or hormone therapy. Surgery carries a risk of significant operative blood loss. For localized JNA, the cure rate obtained by surgery alone can be as high as 90%. Resection with negative margins is required because inadequate margins will result in a high local failure rate.35 Minimally invasive endoscopic resection has recently been proposed for early-stage JNA. Lesions limited to the nasal cavity and/or nasopharynx or lesions with minimal extension through the sphenopalatine foramen are suitable for this procedure. A craniofacial approach is recommended for lesions extending into the pterygoid plates.36,37 Radiation therapy is used either as adjuvant treatment or as sole treatment in locally advanced lesions. Modern techniques such as IMRT have been successfully applied in unresectable and recurrent tumors.38 A wide range of doses have been used, but there is no proof that doses of >36 Gy are advantageous. Chakraborty et al.39 treated eight patients with intensity-modulated radiotherapy with a median dose of 39 Gy. The local control rate was 87% with a mean of follow-up of 2 years. There is no role for cytotoxic chemotherapy in JNA. The role of antiangiogenesis agents is speculative.

LUNG CANCER

LUNG CANCER

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

Pediatric bronchogenic carcinoma is extremely rare, and its management does not differ from that of adults. Most of the tumors occur during adolescence. Histology is more frequently undifferentiated adenocarcinoma or carcinoid tumors rather than squamous cell carcinoma.40

Of 230 cases of primary pulmonary neoplasms of childhood reviewed by Hartman and Shochat,41 <25% were bronchogenic carcinoma. The survival rate was very similar to that of adults, stage for stage.

Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

Fewer than 100 cases of pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) have been reported. This tumor can occur from the neonatal period up to 12 years of age.42 PPB was often mixed with pulmonary blastoma until it was accepted that PPB is purely a pediatric tumor. The main histologic difference between pulmonary blastoma and PPB is the absence of epithelial carcinomatous components in PPB; PPB consists of mesenchymal stroma only. The tumor usually begins in pulmonary tissue, but it can also originate in the pleura or mediastinum.43 According to the Dehner et al.44 classification, three pathologic features can occur: cystic, mixed, and solid. However, it seems that this subdivision has neither prognostic nor therapeutic value.45,46 Some reports also described PPB associated with pre-existing pulmonary cyst.47 It is unclear whether PPB arises in pre-existing malformation or whether PPB induces cystic lesion formation. The report from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry showed that great vessel or cardiac extension is present at diagnosis in 3% of cases.48

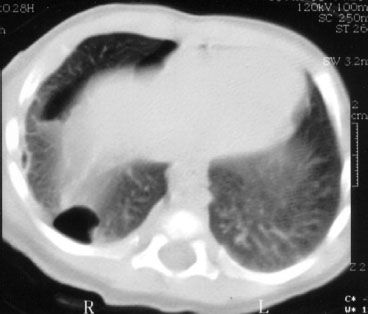

Clinically, PPB exhibits no specific symptoms. The usual presentation is cough, thoracic pain, and fever. Respiratory impairment is unusual. Radiologic findings depend on the extent of the cystic component (Fig. 90.1). The standard treatment is surgery, which can be curative in early-stage disease, but the prognosis is often poor even after complete excision, especially if the size of tumor exceeds 5 cm.49

Priest et al.42 reported only 8% survival rate at 5 years among 50 patients.50 Postoperative radiation therapy can be offered for a positive margin resection or in recurrent disease. The recommended dose is 50 Gy to the tumor bed and, because most of the relapses are local or metastatic, it is our opinion that lymphatic irradiation is not necessary. The value of chemotherapy is controversial. There are, however, long-term survivals reported with multiagent combinations such as actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, etoposide, Adriamycin, and vincristine.43,51–53,54 Multimodal therapy with surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy (10.5 Gy) has been reported with good results at 3 years,55 and recommendations have been published by the International PPB Registry.48

FIGURE 90.1. Pleuropneumoblastoma in a 1-year-old girl.

BREAST TUMORS

BREAST TUMORS

Malignant breast tumors account for <1% of all childhood cancers and <0.1% of all breast cancers.56–59

A review of adolescents seen at the MD Anderson Cancer Center during a 40-year period identified breast cancer in 16 patients <20 years of age. Ten patients had primary adenocarcinoma of the breast, 4 had cystosarcoma phylloides, and 2 had breast metastases from other primary tumors. Four of the 16 patients had a family history of breast disease.60 Roisman et al.61 reported seven female patients, ages 14 to 17 years, who were treated in various hospitals in Israel for malignancy of the breast during 1967 to 1989. There were two cases of undifferentiated carcinoma with positive axillary lymph nodes, two cases of cystosarcoma phylloides, one case of rhabdomyosarcoma, and two cases of malignant lymphoma, one of them Burkitt’s type. Umanah et al.62 reported 1 case (1.2%) of an invasive ductal carcinoma among 84 breast tumor materials from patients aged 10 to 19 years in a Nigerian city.

Breast self-examination is recommended for girls who carry the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, beginning at age 18 to 21 years.63,64 Ultrasonography is the most appropriate initial investigation in any adolescent patient with a breast mass because dense breast tissue adversely affects the quality of mammography.65 MRI is recommended for diagnosing breast cancer when conventional imaging is complex and indeterminate, especially in young patients with dense mammographies.

Juvenile secretory carcinoma of the breast is rare and was first described by McDivitt and Stewart66 in 1966 in seven girls ages 3 to 15 years, all of whom had a benign clinical course. The tumor cells are characterized by abundant mucin- and mucopolysaccharide-containing materials.67 Hormonal receptors are generally negative.68 Local tumor excision alone may be adequate therapy, although simple and radical mastectomies have also been used.68–70

The histology and patterns of spread of adenocarcinoma of the breast in children and adolescents are similar to those in adults. Because most publications refer to isolated cases, neither a consensus of opinion nor specific guidelines exist with regard to treatment. In general, principles of clinical management established for adults should be adopted. Because recurrences were found in 25% of patients treated with excisional biopsy alone, this seems inadequate, and a simple mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection should probably be performed.71 Sentinel lymph node biopsy offers an approach to stage the axillary lymphatic drainage with a lower complication rate than formal dissection.72 On the other hand, McDivitt and Stewart66 believed that the disease tends to run a relatively favorable course and that radical therapy is therefore unnecessary. Hartman and Magrish73 considered it important to avoid radiotherapy in young children, and instead they recommended radical mastectomy.

Inflammatory carcinoma of the breast is extremely rare in children.74,75

There have been case reports of primary lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, radiation-induced sarcoma, and cystosarcoma phylloides of the breast in children.76–81

Cystosarcoma phylloides appears as a large breast mass; in 25% of cases it is bilateral. Norris and Taylor80 were the first to separate benign from malignant lesions in this disorder. The distinction is based on tumor size, stromal invasion, cellular atypia, degree of mitotic activity, focal calcification, and/or patterns of infiltration. Metastases occur in the lungs and bones. Lymph node metastases are extremely rare. Simple or wide local excision or simple mastectomy, with rare local recurrences, may adequately treat histologically benign lesions. In malignant cystosarcoma phylloides some authors recommend radical mastectomy with or without axillary lymph node dissection, and others are in favor of simple mastectomy.82–86 The use of radiotherapy and postoperative chemotherapy in cystosarcoma phylloides is controversial. These modalities should be reserved for locally advanced, palliative, and disseminated cases.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the breast, either primary or metastatic, is rare. Billroth87 reported the first case of primary rhabdomyosarcoma in a 16-year-old girl in 1860. In a series of 108 patients <20 years of age with this malignancy, Howarth et al.88 reported 7 patients who had metastatic tumors to the breast with primary rhabdomyosarcoma located on an extremity or buttock. Six of the 7 patients had alveolar histology. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the breast and other sarcomas of the breast are treated primarily by surgery followed, in most cases, by adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy.

Breast metastases in the pediatric age group include hepatocarcinoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma Hodgkin disease, neuroblastoma, and adenocarcinoma.89

GASTROINTESTINAL TUMORS OF CHILDHOOD

GASTROINTESTINAL TUMORS OF CHILDHOOD

Gastrointestinal tract malignant tumors are relatively rare in children. Carcinoid and hepatobiliary tumors are the most common.90 Others are adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and leiomyosarcoma. More common are benign tumors such as hamartoma, leiomyoma, neurofibroma, and hemangioma.

Esophagus

In most cases, an esophageal tumor is of epithelial origin, either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma. Rarely, sarcomas may develop in the esophagus (leiomyosarcoma, carcinosarcoma, malignant schwannoma). Malignization of a chemical injury to the esophagus has been described.91 Carcinoma of the esophagus may develop in association with Barrett’s esophagus and Cornelia de Lange syndrome.92,93 The most common benign tumor of the esophagus in the pediatric age group is leiomyoma; desmoid and teratoma may also occur.94–96 The management of esophageal cancer in the pediatric age group follows the same guidelines of treatment as in adults.97

Stomach

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the most frequent gastric malignancy in the pediatric age group, followed by leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoblastoma.98 Adenocarcinoma is extremely rare; it may arise in association with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.99 The management of non-Hodgkin lymphoma follows the treatment guidelines of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in adults.

Leiomyosarcoma of the stomach is treated primarily with surgery. Postoperative irradiation is given to patients with high risk of local recurrence (such as positive surgical margins or extension into the retroperitoneum).

As in the adult age group, subtotal gastrectomy with resection of associated lymph nodes is the treatment of choice for children with gastric carcinoma. No data are available on adjuvant radiation–chemotherapy in the pediatric age group. However, based on the results of a randomized study in adult patients with locoregionally advanced gastric carcinoma,100 one could assume that the use of combined irradiation and chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil and leucovorin) after surgery is beneficial.

Radiotherapy guidelines are similar to those for the adult age group. At the time of radiotherapy planning, attention should be given to vital structures such as spinal cord, kidneys, small bowel, and liver. During treatment, acute side effects may occur, such as nausea, weight loss, and fatigue.

Several combination chemotherapy regimens have been used in the adjuvant setting and for locally advanced or metastatic gastric carcinoma. Numerous phase II and phase III studies were reported in the adult age group.101 More than 20% of gastric cancers and up to 33% of gastroesophageal junction tumors show HER2 overexpression.102 This gives new therapeutic options, adding trastuzumab to chemotherapy.103

Small Bowel

According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, the incidence of malignant small intestine tumors is low in patients <30 years of age.104 The most common malignancy of the small intestine in children is non-Hodgkin lymphoma.105 Sarcomas of the small bowel and carcinoids may also develop in children. Small intestine adenocarcinoma may develop spontaneously or in association with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.106

Treatment guidelines are similar to those of the adult age group. Adjuvant irradiation can be given after surgery for duodenal sarcomas or adenocarcinomas arising in the segment fixed to the retroperitoneum or for palliative purposes such as for pain or bleeding.

Colorectal Cancer

Carcinoma of the rectum and the large bowel is rare in children and adolescents. According to the SEER data, approximately 145,000 cases of colorectal carcinoma occur annually in the United States. Of these, only 0.1% occurs in patients <20 years of age.107 Young patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.108 Several genetic conditions may be associated with colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence. These include familial polyposis, Turcot syndrome, Oldfield syndrome, and Gardner syndrome.100,101,102–103,104–108,109,110–112 The genetic events associated with the development of colorectal carcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, from epithelial proliferation, through formation of adenomas, to the sequential development of colorectal malignancy, have been described by Vogelstein et al.113

Similar to the adult age group, signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer are related to the segment of the large bowel where the tumor is located. Because of its rarity in the pediatric and adolescent age groups, diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma is often delayed, and patients usually present with acute symptoms that necessitate urgent laparotomy. Colorectal cancer in the young is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage with metastases involving the omentum, peritoneum, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, ovaries, and sometimes lungs, brain, and bones, and therefore it carries a poor prognosis.114

Colorectal carcinoma is diagnosed by direct fiberoptic colonoscopy. Radiographic studies include barium enema with air contrast, CT scan, and radioisotope studies (fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography [FDG-PET]) to determine metastatic spread. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level is important both as a prognosticator and for follow-up purposes. CA19-9 essay has been less valuable, although some tumors produce CA19-9 without CEA production.

Adenocarcinoma of the colorectum may be well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. The mucinous variety and signet cell types are associated with extremely poor prognosis. Mucinous adenocarcinoma is the most common histotype in the pediatric age group.115 Unlike adult patients, in whom 60% of colonic cancers are located within 25 cm of the anus and in whom the rectum and sigmoid are also common sites for mucinous adenocarcinoma, tumors in children are probably more evenly distributed in all parts of the colon.95,116,117 In a series reported by Andersson and Bergdahl,118 the most common area was the transverse colon (39%). In a series of 20 patients reported by Karnak et al.119 from Turkey, the rectosigmoid area was the most frequent site of location of the primary tumor (65%, the same as in adults).

Surgery is the primary and most effective treatment for colorectal carcinoma. Because of late diagnosis, the rate of complete resection has been less than optimal in children. In the series of Karnak et al.,119 complete resection was possible in only 6 of 20 patients. The surgical guidelines are similar to those of adult patients. Similarly, the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy follows the guidelines of the adult age group. Special attention should be given to radiochemotherapy sequelae on the reproductive system.

Appendix

The most frequent malignant tumors of the appendix in the pediatric age group are carcinoids. These tumors are usually diagnosed incidentally during surgery for acute appendicitis or during other abdominal surgery. Complete surgical removal is the treatment of choice.120,121

Pancreas

Pancreatic tumors are rare in children. The most important types are the functional tumors, pancreatoblastomas, and solid papillary epithelial neoplasms.122,123 The adult form of pancreatic adenocarcinoma rarely occurs in children.

Functional islet cell tumors are characterized by their hormonal activity. The diagnostic procedures and management follow the same guidelines set for adults.

The pediatric type of carcinoma of the pancreas, pancreatoblastoma, is a rare tumor; <100 cases have been reported in the literature. The European Cooperative Study Group for pediatric rare tumors analyzed 20 patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2009.124 The tumor is characterized by adenocarcinomatous tissue with ductal cells, acinar cells, squamoid corpuscles and sometimes islet cell differentiation. These tumors stain positively by periodic acid-Schiff, α-trypsin, and α-keratin, and in many cases can be associated with increased levels of α-fetoprotein (AFP).125–127

In most cases the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas. In patients with a solitary noninfiltrative tumor, complete local resection without radical pancreatoduodenectomy is recommended. Unlike patients with local disease, in whom local resection can be curative, in many other cases the tumor is clearly malignant, with invasion, local recurrences, and nodal and disseminated metastases. The prognosis for these patients is very poor.128,129

Radiation therapy is used in the postoperative setting, in locoregional recurrences, and in the neoadjuvant setting. A dose of 40 to 50 Gy is recommended.127,130 Technical guidelines of radiotherapy planning are similar to those of the adults. Intraoperative radiotherapy for recurrent disease has also been used.

Chemotherapy has been used for unresectable tumors, to treat metastatic disease, or in the adjuvant setting. 5-Fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, actinomycin D, vincristine, vinblastine, mitomycin c, bleomycin, ifosfamide, etoposide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine, alone or in combination, have been used with very modest results.131,132 Because the disease is so rare, it is impossible to set firm guidelines and treatment policies for chemotherapy in pediatric pancreatoblastoma.

Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas, also known as Frantz tumors, are usually encapsulated lesions that can develop throughout the pancreas. They are characterized by cystic or pseudocystic spaces surrounded by residual solid tissue. Only 15% of these tumors are malignant, and they usually occur in female patients at a mean age of 24 years at diagnosis.133

These tumors usually present as an upper abdominal mass. Unlike other malignant pancreatic tumors, their prognosis is excellent after complete surgical excision.134

The adult type of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is extremely rare in the pediatric and adolescent age groups. Signs and symptoms are similar to those of adult carcinoma of the pancreas.130 These tumors are managed according to guidelines of treatment set for adult patients.

TABLE 90.3 HISTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF HEPATOBLASTOMA

Hepatobiliary Tumors

Hepatobiliary tumors are the most common neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract to occur in children. They constitute 0.5% to 2% of pediatric cancer in Europe and in the United States. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurs more frequently in Saharan Africa and the Asia.62,135–139 This geographic clustering may be explained by the high rates of hepatitis B infection and hepatitis B serum antigen positivity.140

Benign hepatic tumors are more frequent than malignant tumors in young children. In older children, malignant tumors become more common. Benign tumors are classified according to the cell of origin: mesenchymal (hemangioma, hemangioendothelioma, hamartoma, peliosis hepatis) or epithelial (cysts, focal nodal hyperplasia, adenoma).141 On rare occasions, radiation therapy may be used for the treatment of hemangiomas.

Malignant tumors of the liver are classified according to the tissue of origin, with hepatocellular tumors (hepatoblastoma [HBL] and HCC) most common, constituting 75% to 90% of primary hepatic malignant tumors of childhood. Other tumors include malignant mesenchymoma, undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma, primary hepatic malignant tumors with rhabdoid features, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, hepatic sinusoid tumors, carcinoid, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Bile duct adenocarcinoma (cholangiocarcinoma) is extremely rare before the age of 30 years. This tumor has been associated with certain rare congenital biliary anomalies, ulcerated colitis, cystic fibrosis, and sclerosing cholangitis.141,142 The liver is also a common site for metastatic disease.

Of the malignant tumors of the liver in childhood, HBL is the most common. HBL occurs almost exclusively in small infants, although isolated instances in older children and in young adolescents have been reported. These tumors occur more frequently among males.

HBL is associated with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and congenital anomalies like hemihypertrophy and cleft palate, Wilms tumor, and glycogen storage diseases.143–146 Although the association between HBL and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome indicates abnormalities on chromosome 11 and loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11p, increased incidence of HBL in families with familial adenomatous polyposis indicates a possible significance for abnormalities of chromosome 5q.145,147

The presenting signs and symptoms are distention of the abdomen, anorexia, vomiting, anemia, fever, and jaundice. Isosexual precocity secondary to human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) secretion by the tumor can be seen in some cases.146

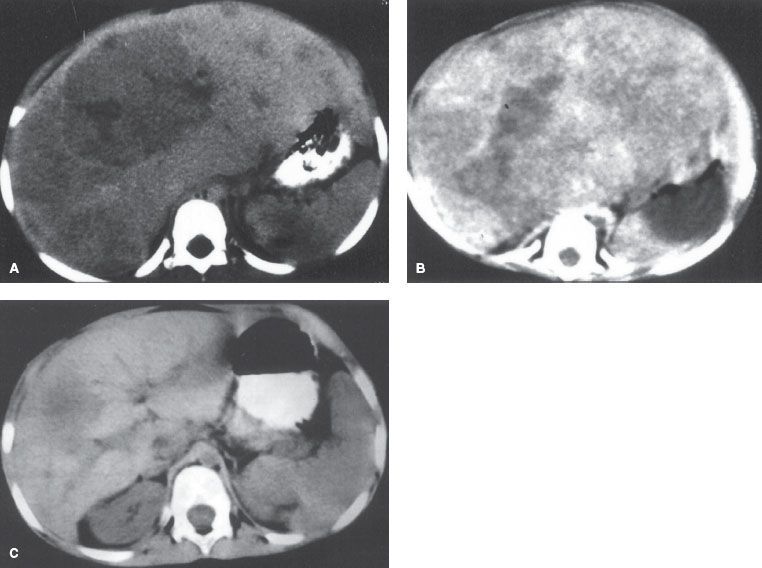

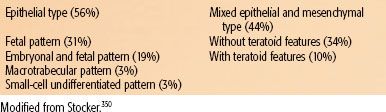

Serum AFP produced by the embryonal endoderm is increased in 84% to 90% of patients with HBL.148 HCG and cystathionase may also serve as tumor markers.149 Histologically, hepatoblastomas (Fig. 90.2) are classified into five subtypes (Table 90.3). These subtypes can occur together in varying properties, but present definitions do not take this into account, which makes it difficult to relate a specific histologic subtype with prognosis. Pure fetal histology has a better outcome, but the definition of “pure fetal” is not clear. The prognosis of the rare (3%) small-cell undifferentiated subtype is poor. In long-term survivors of HBL, the most common histologic variant is the conventional type with predominantly fetal cell patterns. A trial performed by the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) and the Children’s Cancer Study Group (CCSG) demonstrated the importance of the distinction between fetal hepatoblastoma and the other histologic subtypes in stage I disease.150 A German study (HB 89–94)151 identified several poor prognostic factors in HBL: metastatic disease, AFP >1,000,000 ng/mL, extrahepatic and intrahepatic vascular invasion, multifocal disease, involvement of both liver lobes, stage (TNM), and poorly differentiated epithelial histology.

HCC is the second-most-common primary malignant liver tumor in the pediatric age group and accounts for about one-fourth to one-third of hepatic malignancies. Although reported in children as young as 21 months, most reports indicate that HCC usually develops in early adolescence.152,153 This is in contrast to HBL, which occurs primarily in infancy and is seldom seen in children older than 3 years. Similar to HBL, HCC occurs mainly in males.154,155 The fibrolamellar carcinoma variant of HCC occurs mainly in young adults around the age of 20 years but has also been reported in childhood.156,157

Approximately 25% of HCC cases in childhood are associated with cirrhosis secondary to biliary atresia, Fanconi anemia, glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency, and hereditary tyrosinemia.158 The most important known etiologic factor for HCC is the high incidence of maternal transmission of the hepatitis B surface antigen in Africa and Asia.159,160 Other etiologic factors include exposure to aflatoxins, hepatic fibrosis, anabolic steroids, inherited disorders of metabolism, membranous obstruction of the inferior vena cava, and possibly ethanol abuse.139,155,161 However, these etiologic factors apply mostly to HCC in the adult age group. In adult Black South African patients, deletions of alleles on chromosome 17p and P53 (codon 249) have been identified162,163; the exact molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of HCC are not known.

Similar to HBL, two-thirds of children with HCC have an elevated AFP.164 AFP levels are high in the healthy newborn and drop rapidly by the age of 1 month and should not be detectable by age 2 years.165 Initial AFP level is a significant prognostic factor: In a study performed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group,166 the mortality in HCC was 1.8 times higher in patients with strongly positive AFP. AFP is an indicator of tumor growth and can serve as a valuable marker of response to therapy. After complete tumor resection, AFP level should return to normal within 2 months.167 Increasing levels of AFP during the follow-up period after surgery indicate local recurrence or metastatic disease.164

The CCSG intergroup and POG staging systems for primary malignant liver tumors are based on resectability and on the histologic subtype (Tables 90.4168,169 and 90.5170).

FIGURE 90.2. A 7-year-old girl with hepatoblastoma at diagnosis (A), after one cycle of chemotherapy (B), and after four cycles of chemotherapy before right hepatic lobectomy (C).