Uncommon B-Cell Lymphom

Multiple uncommon B-cell lymphomas each account for only a small percentage of non-Hodgkin lymphomas overall, but should be familiar to clinicians based on their unique clinical and pathologic features, natural histories, and approaches to therapy. These diseases reviewed in this chapter include Burkitt lymphoma, plasmablastic lymphoma, primary effusion lymphoma, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, hairy cell leukemia, and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas.

BURKITT’S LYMPHOMA

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Burkitt’s lymphoma is a highly aggressive mature B-cell lymphoma accounting for approximately 3% of new non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) diagnoses annually in the United States. The disease has endemic, immunodeficiency-associated, and sporadic variants. Endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma was the initial entity described as a rapidly progressive tumor most commonly occurring in the jaws of children in equatorial Africa, Brazil, and Papua New Guinea (1). This subtype occurs at a median age of 5–7, and is uniformly positive for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Immunodeficiency-associated Burkitt’s lymphoma occurs most commonly in HIV-infected individuals, but may also be seen in patients following solid-organ transplantation or other immunodeficient states. These tumors express the EBV virus in approximately one-third of cases. Sporadic Burkitt’s lymphoma occurs in healthy adults with a male predominance and a median age of 30–40 (2, 3). EBV is usually negative in immunocompetent patients.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

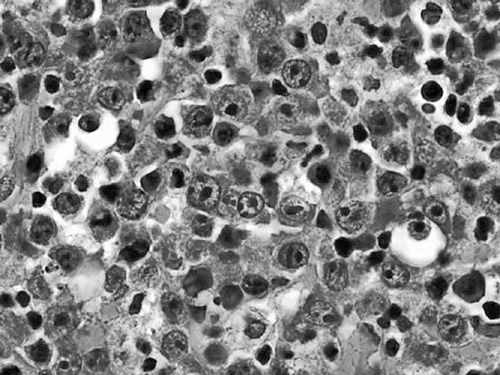

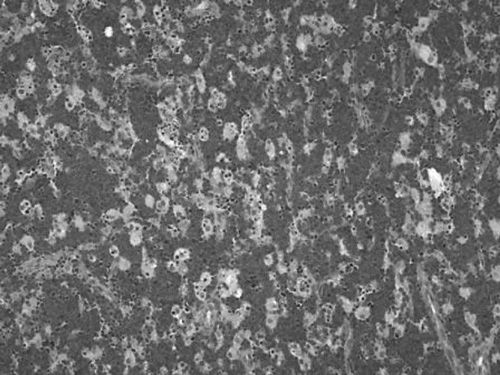

Diagnosis should be made by excisional biopsy. Pathologically, Burkitt’s lymphomas are characterized by a diffuse infiltrate of monomorphic medium-sized lymphoid cells with coarse chromatin, basophilic cytoplasm, frequent mitoses, and interspersed tingible-body-macrophages ingesting apoptotic debris and giving the tumor the classic “starry sky” appearance on low-power microscopy (Figure 36-1) (4). Immunohistochemical staining shows the cells to express pan B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, and CD79a) and markers of germinal center derivation (CD10 and BCL6). BCL-2 should be negative. Staining for Ki67 demonstrates a proliferation fraction that is usually approaching 100%. The genetic sine qua non is the rearrangement of the MYC proto-oncogene on chromosome 8, usually in the t(8;14), or occasionally the variant translocations t(2;8) or t(8:22) where the site of translocation of MYC is to the transcriptionally active immunoglobulin heavy-(chromosome 14) or light-chain genes (kappa on chromosome 2 or lambda on chromosome 22). In endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma, the MYC breakpoint is usually upstream of the first coding exon and the immuno- globulin heavy chain breakpoint is in the joining (J) region. In sporadic and HIV-associated Burkitt’s lymphoma, the MYC breakpoint is often between exons 1 and 2 and the heavy chain breakpoint is in the switch region. These distinct molecular changes are not always noted. The MYC translocation in Burkitt lymphoma typically occurs in the context of a simple karyotype. In settings of atypical morphologic, immunohistochemical, or genetic features, such as BCL-2 expression or a complex karyotype, those cases would generally not be classified as a Burkitt’s lymphoma, but rather as B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. Such cases generally occur in older adults and will often be characterized as a “double hit lymphoma” harboring dual translocations of MYC and BCL-2, usually in the setting of a complex karyotype, and carrying a significantly worse prognosis than Burkitt lymphoma of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (5) (Figure 36-2).

Figure 36-1 Burkitt’s lymphoma. Low-power view showing monomorphic medium- sized malignant cells effacing the lymph node architecture with areas of clearing formed by tingible body macrophages ingesting apoptotic debris.

Figure 36-2 Overall survival of double hit lymphoma compared to Burkitt’s lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. (From Snuderl M, et al. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:327-340.)

Burkitt’s lymphoma presents clinically as rapidly progressive nodal and/or extranodal masses. Nonendemic cases of Burkitt’s lymphoma have a predilection for abdominal sites, particularly the ileocecal valve, but may present virtually anywhere in the body including any nodal or extranodal region, the head and neck, bone marrow, liver, kidneys, breast, soft tissues, skin, or central nervous system. Systemic “B” symptoms of fever, drenching night sweats, and weight loss may occur. Cases of immunodeficiency- associated Burkitt’s lymphoma similarly present at advanced stage, often involving both nodal and extranodal sites. LDH is elevated in the majority of patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma, and spontaneous tumor lysis may be present at diagnosis.

Following diagnosis, staging for Burkitt’s lymphoma includes full body CT scans, ideally in concert with a full body PET scan given the increased sensitivity of this modality, particularly for extranodal sites of disease. The bone marrow is assessed with a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, and spinal fluid should be evaluated by cytology and flow cytometry. HIV status should be checked along with viral load and CD4 count. Most HIV-associated Burkitt’s lymphomas occur in patients with a median CD4 count in the 200s (2). Hepatitis B serologies should be checked given risk of HBV reactivation in patients treated with intensive chemotherapy, particularly when rituximab is included. Tumor lysis labs should be checked at baseline. Evaluation of cardiac ejection fraction with echocardiography or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan is advised in anticipation of anthra- cycline-containing therapy.

In addition to Ann Arbor staging, Burkitt patients may be classified as either low- or high-risk based on extent of disease and LDH value. Low-risk patients have a completely resected mass or limited disease less than 10 cm, a favorable performance status, and a normal LDH. All other patients are considered high risk.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

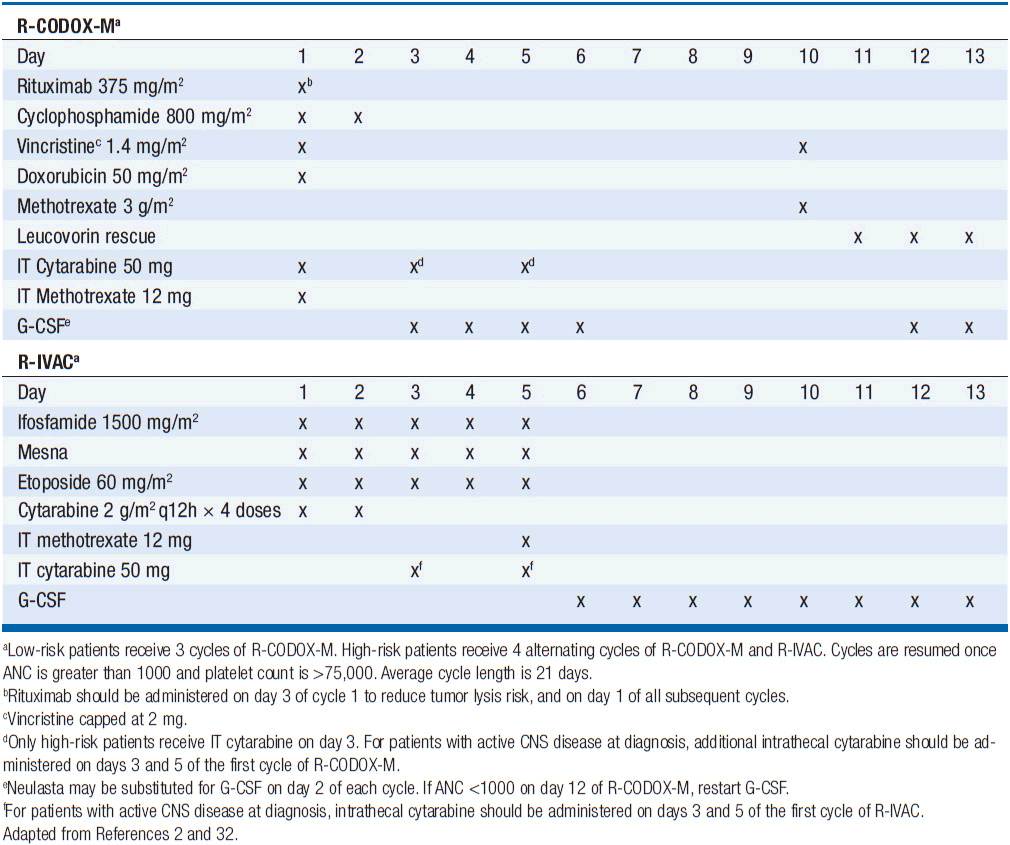

Treatment has historically been with highly intensive alternating cycles of chemotherapy directed at both the systemic and CNS compartments (6, 7). The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab has been included with intensive chemotherapy based on noncomparative data showing encouraging results when added to combination chemotherapy (2, 8). The CODOX-M/IVAC regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide, and cytarabine) with rituximab produces a 3-year overall survival of nearly 80% (Table 36-1) (2). Patients with low-risk disease receive 3 cycles of the R-CODOX-M alone, while patients with high-risk disease receive 4 alternating cycles of R-CODOX-M and R-IVAC. Adverse prognostic factors include advanced age and involvement of the CNS at diagnosis. HIV infection is not an adverse predictor of outcome, but does require increased attention to supportive care including white blood cell growth factor support, prophylactic antibiotics against opportunistic infections, and attention to drug-drug interactions with the HIV-directed antiretroviral therapy. The R-HyperCVAD/MA regimen (rituximab, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine) administered for 8 alternating cycles also produces encouraging results with 3-year overall survival approaching 90% (Table 36-2) (8). Both regimens include intrathecal chemotherapy for prophylaxis of the CNS, with additional intrathecal doses included for patients with an involved CNS at diagnosis. The overall course of therapy with HyperCVAD is twice as long as the complete course of therapy for CODOX-M/IVAC. Both regimens are highly intensive with virtually all patients experiencing grade 4 hematologic toxicity, and so supportive care for all patients is essential, including blood product support as needed, white blood cell growth factor support, antibiotic prophylaxis against P. jiroveci, and tumor lysis prophylaxis and monitoring at initiation of therapy. Patients with HIV should receive concurrent combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in addition to intensive supportive care and infectious prophylaxis. Elderly patients tolerate these intensive regimens poorly, and so less intensive approaches should be considered. The infusional dose-adjusted EPOCH-R regimen (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and rituximab) is better tolerated than the highly intensive approaches and has shown superb efficacy in a small study in predominantly younger patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma (Table 36-3) (9). This regimen is currently under study in a broader Burkitt lymphoma population in a phase II clinical trial. If these data are validated in the multicenter study, EPOCH-R may emerge as an appealing alternative to the more intensive regimens currently employed for the majority of patients.

PLASMABLASTIC LYMPHOMA

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a highly aggressive mature B-cell lymphoma initially described in HIV patients with a predilection for the oral cavity (10). Since the initial report, this disease has also been seen in HIV noninfected patients accounting for close to one-third of PBL cases, and includes patients following solid organ transplantation, as well as immunocompetent adults (11). The majority of patients are men, and the median age is approximately 40 years in HIV-infected patients and 60 years in patients without HIV. Most patients present with advanced stage disease, usually involving extranodal sites, oral cavity and sinuses, orbit, gastrointestinal tract, bone, skin, soft tissues, and central nervous system. LDH is commonly elevated. Among HIV patients, the median CD4 count is 165 cells/mm3 (12).

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

PBL is characterized histologically by large lymphoid cells that may have either immunoblastic or plasmacyctic differentiation (Figure 36-3) (4). Mitoses are frequent and the Ki67 proliferation fraction is generally close to 100%, reflecting the highly aggressive disease kinetics. By immunohisto-chemistry, the cells are usually negative for CD20 and positive for plasma cell markers CD38 and CD138. EMA and CD30 are commonly expressed, and EBV is detected in the majority of cases by in situ hybridization for EBV RNA. HHV8 is negative, unlike in primary effusion lymphoma. PBL should be evaluated for MYC rearrangements, which have been detected in approximately half of cases (13).

Figure 36-3 Plasmablastic lymphoma. High-power view of large malignant B-cells in PBL with an immunoblastic appearance.

Staging should include a full body PET/CT given the role of functional imaging in high-grade lymphomas and increased sensitivity for extranodal sites. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy should be performed. Lumbar puncture is recommended, as well as brain MRI for patients with CNS symptoms. All patients should have HIV checked, as well as CD4 count and viral load for HIV-infected patients. Spontaneous tumor lysis syndrome may occur, so tumor lysis labs should be checked at baseline, as well as an echocardiogram if an anthracycline-containing regimen is planned.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

PBL is a highly proliferative neoplasm and is rapidly fatal without therapy. The estimated median survival is 14 months, with 31% of patients alive at 5 years (12). Patients presenting with localized disease enjoy a more favorable prognosis. As with other HIV-associated lymphomas, cART should be considered a vital component for therapy in all patients with PBL in the setting of HIV infection, but rapid initiation of chemotherapy is essential. CHOP is associated with a high rate of treatment failure with low survival rate, and is not recommended, and so the more intensive regimens typically used in Burkitt’s lymphoma should be considered, including dose-adjusted EPOCH, CODOX-M/IVAC, or HyperCVAD (Tables 36-1 through 36-3). Rituximab should be included only for the small number of cases that express CD20. Patients with localized disease should have radiation therapy included as combined modality therapy given the historic chemoresistance of this disease. All patients receiving intensive chemotherapy should be monitored for tumor lysis syndrome and receive supportive care with G-CSF and antibiotic prophylaxis against P. jiroveci and other pathogens as dictated by CD4 count.

The proteosome inhibitor bortezomib is used routinely in the management of the plasmacytic neoplasm multiple myeloma, providing rationale for use in PBL. Presently, only case reports exist to support efficacy, and further data are needed. CD30 is usually expressed in PBL, making the CD30-targeted agent brentuximab vedotin also worthy of investigation in the setting of a clinical trial.

PRIMARY EFFUSION LYPHOMA

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), also known as body cavity lymphoma, is an uncommon B-cell lymphoma most commonly seen in advanced AIDS. Rare cases have also been observed in the absence of HIV infection, including in patients following solid organ transplantation, or in the setting of chronic hepatitis C or autoimmune diseases. PEL is uniformly associated with HHV-8 infection (also called the Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus), the same viral pathogen that causes Kaposi’s sarcoma and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Patients with one HHV-8-associated disease are at increased risk for developing another. Given that most of these patients have advanced AIDS, concurrent opportunistic infections are also common, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis at presentation.

Patients typically present with a pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, or ascites. The leptomeninges are a rare site of involvement. Clinical presentation is related to the site of the effusion such as shortness of breath in pleural or pericardial PEL, and abdominal distention in patients with peritoneal disease.

An uncommon variant of this rare lymphoma may occur as solid tumors, often in extranodal locations, but with the same morphologic and immunohistochemical features and associated HHV8 expression. These cases have been dubbed “extracavitary” or “solid-phase” PEL.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is by aspiration of fluid from the involved body cavity for cytologic evaluation, flow cytometry, and cell block analysis with immunohistochemistry. Any associated solid tumors should also be biopsied. Given that PEL may present with concomitant Castleman’s disease or Kaposi’s sarcoma, adenopathy and skin lesions should be evaluated and biopsied. Attention should also be paid to possible concomitant opportunistic infections in patients with HIV and low CD4 counts.

The malignant effusion is characterized by large lymphoid cells that usually have plasmacytic differentiation with expression of CD45, CD30, CD38, and CD138, and no CD20 expression. HHV8 infection is a defining pathologic feature and can be detected by staining for viral gene product LANA-1. EBV coinfection is present in the majority of cases and is optimally detected by in situ hybridization for EBV RNA.

Staging should include full body CT scans with consideration of PET imaging as this has improved sensitivity for extranodal sites. Bone marrow biopsy is usually obtained.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Prognosis of PEL is poor, with an estimated median survival of 6 months (14). The lymphoma rarely disseminates outside of body cavities, but the prognosis is driven in large part by the underlying HIV that is present in most patients with this disease resulting in death due to advanced AIDS and opportunistic infections, as well as progressive lymphoma. Adverse predictors of prognosis include poor performance status and absence of prior cART at the time of diagnosis (14).

Initiation of cART is standard as a vital component of treatment, and has been associated with responses in the absence of chemotherapy, and an improved outcome. CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) has a reported response rate of 42% but with a short overall survival (15). The dose-adjusted EPOCH regimen (16) has been well studied in other HIV-associated lymphomas and should be considered based on encouraging efficacy in HIV-associated DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma, but the efficacy specifically in PEL is unknown. Rituximab should not be routinely included given the CD20 negativity in this tumor, but can be added in rare CD20+ cases. A number of novel approaches hold promise as effective therapies as well. Antiviral therapy carries appeal given the HHV-8-mediated pathogenesis, though the cells are lytically infected and thus not sensitive to traditional agents like ganciclovir. Induction of the lytic phase of the virus may sensitize the cells to antiviral therapy, and this is a subject of investigation in clinical trials of HHV-8- and EBV-mediated lymphomas. Intrapleural cidofovir has been reported in case reports to induce responses, and may be considered in patients who are not candidates for systemic chemotherapy (17). The anti-CD30 antibody drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin holds promise as an effective targeted therapy given the superb activity in other CD30+ diseases Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma, and is currently under investigation.

LYMPHOMATOID GRANULOMATOSIS

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LyG) is a rare EBV-associated angiocentric and angioinvasive lymphoproliferative disease that primarily involves extranodal sites. It generally occurs in patients age 50–70 year old and with a 2:1 male predominance (18). Though the disease may occur in immuno-compromised patients such as HIV patients, organ transplant recipients, or those with congenital immunodeficiency, this disease occurs most commonly in previously immunocompetent individuals. All patients have evidence of impaired immune function at diagnosis (19), raising the question of whether the disease causes the immunodeficiency, or conversely is occurring in the setting of a previously undiagnosed immune-deficient milieu. The lungs are involved in nearly all patients, usually bilaterally, followed by kidneys, skin, central nervous system, and liver. The presenting symptoms are usually cough, dyspnea, and chest discomfort related to pulmonary involvement, often associated with fever and malaise. The subacute onset with fevers and respiratory symptoms will often lead to an initial diagnosis of a respiratory infection. Respiratory symptoms and chest x-ray findings of bilateral lung nodules that predominate in the middle and lower lobes may wax and wane. Skin lesions of LyG are most commonly maculopapular and may ulcerate. Patients may present with symptoms referable to CNS involvement which occurs in approximately one-third of patients and may cause altered mental status, cranial neuropathy, gait disturbance, or seizures (20).

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis may be difficult to make given the nonspecific clinical presentations that are more suspicious for respiratory infections or primary neurologic diseases. Given the polymorphous nature of the infiltrate, fine needle and core needle biopsies are usually nondiagnostic and so wedge biopsies via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery are recommended. On biopsy, the lesions are characterized by an angioinvasive polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, immunoblasts, and histiocytes (4). A variable number of large atypical EBV+ lymphocytes are present. The disease is graded based on the number of large EBV+ cells in the infiltrate with the cells being infrequent or absent in grade 1 lesions, occasional (5–20 per high power field) in grade 2 lesions, and numerous (>50/high power field) in grade 3 lesions (4). Grade 3 lesions may contain large aggregates or sheets of the atypical cells, and necrosis may be present. The cells are typically positive for CD20 and variable for CD30. CD15 is absent. The background T cells are more commonly CD4 than CD8. Clonality by immunoglobulin gene rearrangements can be demonstrated in the majority of grade 2 and 3 lesions, but may not be seen in grade 1. Laboratory studies are usually unremarkable, though a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia may be seen. CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed at diagnosis, and brain MRI if CNS symptomatology is present, though this disease is not traditionally staged using the Ann Arbor system.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Historically, prognosis was poor with a median survival of less than 2 years (20). Some patients, particularly with grades 1 and 2 disease, may have a lengthy waxing and waning natural history, while grade 3 lesions are typically aggressive with a short overall survival without aggressive treatment. For patients with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic grades 1 and 2 disease, close observation is appropriate as spontaneous remissions may occur. Glucocorticoids have been utilized with little success with most patients doing poorly (21). Interferon has been utilized for patients with grades 1 and 2 disease starting with a dose of 7.5 million units thrice weekly and escalated based on response (18). Sixty percent of patients achieved a complete remission, including the majority of patients with CNS disease, but the median time to response is 9 months. The progression-free survival at 5 years was 56%. Among patients with grade 3 disease, response to interferon is low, but the dose-adjusted EPOCH-R regimen produced a complete response rate of 66% and 40% progression-free survival at 2 years (Table 36-3) (18). Rituximab either alone or in a low-intensity chemoimmunotherapy platform such as R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) is a reasonable strategy in patients who cannot tolerate intensive combination chemotherapy, but evidence of success is limited to case reports with no prospective clinical trials reported (22, 23). Patients may succumb to infectious complications given the immune-deficiency associated with LyG, or may undergo transformation to high-grade DLBCL. Such patients should be treated with aggressive chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as dose-adjusted EPOCH-R or R-CHOP, or with traditional second-line DLBCL regimens if those regimens have already been employed.

HAIRY CELL LEUKEMIA

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

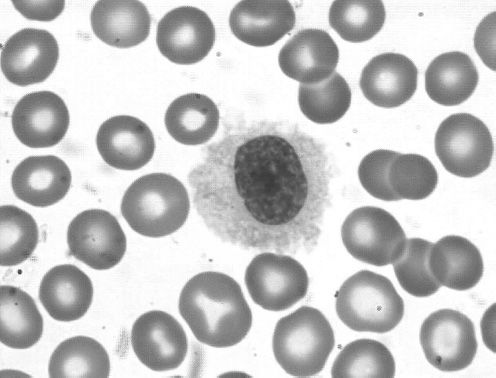

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disease initially described in 1958 as leukemic reticuloendotheliosis (24). HCL occurs at a median age of 50 with a male predominance of approximately 5:1. The name derives from the circulating cells that may be observed in the peripheral blood as medium-large size lymphoid cells with oval nuclei and abundant pale blue cytoplasm with fine circumferential hair-like projections (Figure 36-4). Despite the name of “leukemia,” most patients present with a very small amount of circulating disease. The dominant disease burden in HCL is found in the bone marrow and spleen (Figure 36-5), leading to the most common presentation of symptomatic splenomegaly and pancytopenia. Lymphadenopathy is uncommon. Absolute monocytopenia is observed in the majority of patients. Patients may present with bleeding due to thrombocytopenia or recurrent opportunistic infections.

Figure 36-4 Hairy cell leukemia. Peripheral smear showing a typical hairy cell with an oval nucleus, abundant cytoplasm and ruffled indistinct border with circumferential fine hairlike projections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree