Cholangiocarcinoma and Gallbladder Cancers

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are invasive carcinomas that arise from the epithelial lining of the gallbladder and bile ducts. Cholangiocarcinomas are cancers arising in the intrahepatic, perihilar, or distal biliary tree, exclusive of cancers of the gallbladder and ampulla of Vater (Figure 46-1). Tumors involving the proper hepatic duct bifurcation are collectively referred to as Klatskin tumors, and are subdivided further using the Bismuth-Corlette Classification based on involvement of the left and right hepatic ducts, and focality versus multifocality of the tumor (1).

FIGURE 46-1 Classification of biliary tract cancers. (From de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, et al. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341. Copyright © 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.)

The vast majority of cholangiocarcinomas and gallbladder cancers (GBCs) are adenocarcinoma. While anatomically these malignancies are related, each has a distinct clinical presentation, molecular features, metastatic pattern, and prognosis. This group of tumors is characterized by local invasion, extensive regional lymph node metastasis, vascular encasement, and, especially with GBC, distant metastasis. Complete surgical resection offers the only chance for cure; rates of surgical resectability vary by primary location. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas have the highest resectability rates compared to Klatskin and intrahepatic tumors (2). Among GBCs, only 10% of patients present with T1 tumors (those confined to the gallbladder muscle wall) unless they are found incidentally at cholecystectomy (3). Among those patients who do undergo “curative” resection, recurrence rates are high. BTCs have a poor prognosis; their 5-year survival rates are 5%–10% or less. The median survival of patients with unresectable or metastatic BTC at diagnosis is less than a year.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Assessing incidence and prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma is difficult because intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is grouped with hepatocellular carcinoma. Collectively, there are an estimated 28,700 liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers annually in the United States. Approximately 10%–15% of these tumors are estimated to be intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (4, 5). Extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder cancers are grouped together. They total about 13,000 new cases annually in the United States, of which 9810 cases are extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, the remainder primary GBC (4). For unclear reasons, the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has been rising over the past two decades in Europe and North America, Asia, Japan, and Australia. The risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma and GBC are shown in Table 46-1. For cholangiocarcinoma, these factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), congenital abnormalities of the biliary tree (Caroli’s syndrome, congenital hepatic fibrosis, choledochal cysts), parasitic infection of the liver flukes of the genera Clonorchis and Opisthorchis, hepatolithiasis, toxic exposures including radiologic contrast agent thorotrast (a radiologic contrast agent banned in the 1960s for its carcinogenic properties), Lynch syndrome II and multiple biliary papillomatosis, and possibly hepatitis C infection (6).

PSC is strongly associated with ulcerative colitis (UC). The incidence of colitis is around 90% in patients with PSC. Nearly 30% of cholangiocarcinomas are diagnosed in patients with UC and PSC. The annual incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC has been estimated to be between 0.6% and 1.5% per year, and lifetime risk is 10%–15% (7). Cholangiocarcinoma develops at a significantly younger age (between the ages of 30 and 50 years) in patients with PSC than in patients without PSC. In the United States, GBC is the fifth most common GI cancer, and the most common involving the biliary tract (8). Among both Southwestern Native Americans and in Mexican-Americans, GBC is the most common GI malignancy (9). Worldwide, there is a prominent geographic variability in GBC incidence that correlates with the prevalence of cholelithiasis. High rates of GBC are seen in Chile, Bolivia, Japan, and Southeast Asia (10). Incidence steadily increases with age. Women are affected two to six times more often than men, and GBC is more common in Caucasians than in blacks (11).

For GBC, several conditions associated with chronic inflammation are considered risk factors, which include gallstone disease, porcelain gallbladder, gallbladder polyps, chronic salmonella infection, congenital biliary cysts, and abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction.

Gallstones are present in 70%–90% of patients with GBC, and there appears to be a relationship between gallstones and the development of GBC (12). Those with symptomatic gallbladder disease, larger gallstones, and longer duration of cholelithiasis have higher risks for the development of GBC. It should be noted that despite the increased risk of GBC in patients with gallstones, the overall incidence of GBC in patients with cholelithiasis is only 0.5%–3%.

An increased risk of GBC has been described in workers in industries involved in manufacture or processing of oil, paper, chemicals, shoes, textiles, and cellulose acetate fiber, and in miners exposed to radon. An association between medications and GBC has yet to be established.

PATHOLOGY

The majority of bile duct and gallbladder cancers are adenocarcinoma, although other histologic types are occasionally found, including small cell cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma. The molecular pathology is not well understood in these diseases. A subset of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas harbor mutations in the metabolic enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), which may prove to be a druggable target in the future (13).

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical presentations may vary depending on the location of the disease. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas usually become symptomatic when the tumor obstructs the biliary drainage system, causing painless jaundice. Common symptoms include pruritus, abdominal pain (a constant dull ache in the right upper quadrant), weight loss, and fever. Patients with underlying PSC and cholangiocarcinoma tend to present with declining performance status and cholestasis. Other symptoms related to biliary obstruction include clay-colored stools and dark urine. Patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas usually present with a history of dull right upper quadrant pain and weight loss, an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and normal or only slightly elevated serum bilirubin levels.

Patients with early invasive GBC are most often asymptomatic, or have nonspecific symptoms that mimic or are due to cholelithiasis or cholecystitis. The diagnosis of GBC should be considered if compression of the common hepatic duct by an impacted stone in the gallbladder neck is identified (the Mirizzi syndrome). Patients with more advanced GBC may present with abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, or vomiting, malaise, and weight loss.

DIAGNOSIS

IMAGING

IMAGING

Ultrasound (US) is often used as the initial imaging test due to its easy availability. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas would appear as a mass lesion on US. Perihilar and extrahepatic cancers may not be readily detected, especially if small but indirect signs (biliary ductal dilatation throughout the obstructed liver segments) may point toward the diagnosis.

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for detecting intrahepatic tumors, assessing the level of biliary obstruction, and confirming the presence of liver atrophy and distant metastases. Ductal dilatation in both hepatic lobes with a contracted gallbladder suggests a Klatskin tumor, which sits at the bifurcation of the common, left, and right hepatic ducts, while a distended gallbladder without dilated intrahepatic or extrahepatic ducts suggests cystic duct obstruction by a stone or tumor. A distended gallbladder with dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts is more typical of tumors involving the common bile duct because the obstructive segment is more distal. Dilatation of the ducts within an atrophied hepatic lobe, in conjunction with a hypertrophic contralateral lobe (the atrophy–hypertrophy complex), suggests invasion of the portal vein (14).

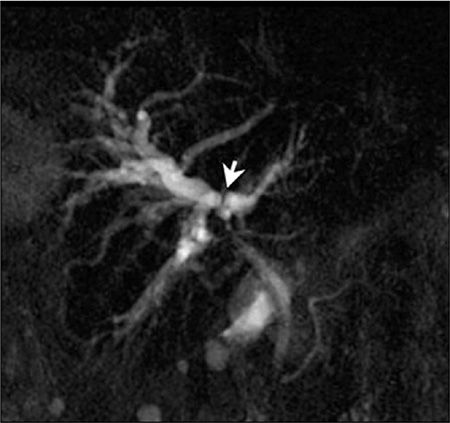

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a noninvasive technique for evaluating the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 46-2). Unlike conventional endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP), MRCP does not require contrast material to be administered into the ductal system, thus avoiding the morbidity associated with endoscopic procedures and contrast administration. MRCP has advantages over CT because it not only images the liver parenchyma and intrahepatic lesions but also creates a three-dimensional image of the biliary tree (allowing assessment of the bile ducts both above and below a stricture) and vascular structures. MRCP provides information about disease extent and potential resectability that is comparable to the combined information obtained from CT, cholangiography, and angiography.

FIGURE 46-2 Klatskin tumor shown on MRCP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree