In patients with breast cancer, the presence of nodal metastases limits the therapeutic options and also indicates worse prognosis. When a potentially “early” curable cancer has been detected, the next most critical step is therefore to determine whether the nodal basins are involved as part of the staging process. The TNM classification system has been revised to better reflect the prognostic implications of the discovery of lymph node metastasis in the various nodal basins draining the cancer-containing breast.1

A few points must be kept in mind when using imaging modalities in general and US in particular to detect lymph node metastases from breast cancer:

- With all recent imaging modalities, the criteria for the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis remain to be defined (and evaluated).

- There are multiple nodes in the axilla, and a one-to-one correlation between the nodes imaged in vivo and the nodes examined pathologically from the axillary node dissection surgical specimen is rarely—if ever—possible, which may lead to errors in the reporting of an imaging modality’s diagnostic accuracy. A satisfactory solution would be to perform an image-guided needle biopsy of any abnormal node with placement of a metallic marker for subsequent identification during the pathologic examination of the surgical specimen from axillary node dissection.

- Imaging techniques that rely on blood perfusion cannot be used for ex vivo examination of surgical specimens from axillary node dissection.

- Currently, no imaging modality can detect micrometastases (< 2 mm in diameter), the significance of which remains controversial. Although micrometastases possibly affect long-term survival, there is debate about whether their presence should alter patient management.

- Multiple mildly abnormal nodes in the same nodal basin are probably benign.

- If similar mildly abnormal nodes are found in the contralateral basin, then the indeterminate nodes in question are probably benign (with the exception of lymphoma or leukemia).

- If only one or a few nodes are abnormal and other adjacent nodes appear completely normal, then these nodes are suspicious for metastasis until proven otherwise, usually via US-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA).

Recent advances in US equipment used for small body parts include very-high-frequency and multiarray transducers that operate at peak frequencies of up to 17 MHz and provide exquisite spatial resolution. Such transducers allow visualization of lymph node metastases as small as a few millimeters.

Among recent image-processing techniques, real-time compound scanning, which was initially predicted to provide higher-quality images than those attainable with conventional US, has not proved as beneficial as hoped. In fact, in our experience, the significant blurring associated with this technique has a negative effect on image quality.

Tissue harmonic imaging slightly increases spatial resolution and boosts contrast. In our experience, though, it does not provide any substantial benefit in the US evaluation of nodal metastases.

Three-dimensional US is still investigational and is not expected to provide a breakthrough in the evaluation of the nodal basins in the near future.2 It might be helpful in facilitating the guidance of percutaneous needle biopsy.

Over the last decade, the sensitivity of power Doppler US (PDUS) systems has greatly increased, allowing not only detection of the mere presence of Doppler signals within a node but also detailed mapping of the normal versus disturbed nodal vascularity. This is expected to help differentiate between benign and malignant nodes.

Recently, elasticity imaging with US (elastography) has been reported as a promising adjunct imaging modality to conventional US.3 When several elastography-capable scanners became available in our section 2 years ago, our expectations were that elastography might help discriminate between firm metastatic nodes and soft benign nodes. However, our hopes did not materialize and our preliminary experience of elastography of axillary nodes with current equipment has been disappointing. This issue should be reevaluated when more refined equipment is available.

Examination of the nodal basins is performed with the patient supine. The arm is elevated for examination of the axilla and brought back down for examination of the infraclavicular region, supraclavicular fossa, and low neck. Examination of the internal mammary nodes is done by scanning along the edge of the sternum. For the last 15 years at MD Anderson Cancer Center, we have included systematic examination of the ipsilateral axilla and internal mammary chains in the US breast examination of patients who have or have had breast cancer. If suspicious nodes are demonstrated, examination of the nodal basins is extended to include the supraclavicular fossa and the low neck.4

At the least doubt, examination of the contralateral nodal basin is performed. This usually (although not always) provides a reference for normality.

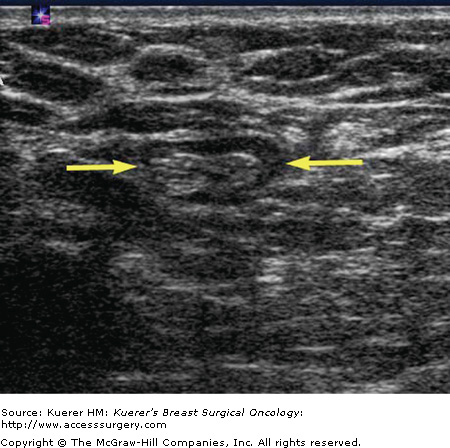

In normal adults, the axillary lymph nodes appear as ovoid or elongated (sometimes sausage-shaped) structures containing a large amount of fat, which is usually (but not always) echogenic (Fig. 34-1). PDUS shows harmonious vascular branching, which radiates from the hilum toward the periphery of the node.

During breast-feeding and for a few months afterward, axillary nodes become moderately swollen and hypoechoic. Such an appearance may be confusing and misinterpreted as suspicious for metastasis in a woman diagnosed with breast cancer postpartum.

A special mention must be given to intramammary nodes. They frequently appear on mammograms in the outer breast with a characteristic appearance. However, when they grow, a US examination may be required to confirm their benign nature. The demonstration of a small rounded structure with a central echogenic component and hilar vascularization on PDUS is pathognomonic of a benign intramammary node.

The US diagnosis of a lymph node metastasis is based on the enlargement and/or focal deformity (bulge) at the periphery of the node and—at least as important—on the marked decrease in echogenicity exhibited by an intranodal metastatic deposit. Because the lymph circulates from the periphery to the hilum of the node, early metastatic deposits develop preferentially at the periphery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree