The status of the axillary lymph nodes is the most significant factor predictive of long-term survival in patients with breast cancer. Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is an effective staging procedure and provides durable local control with a low rate of recurrence (NSABP B-4).1 Furthermore, although ALND has never been associated with an improvement in overall survival in individual randomized controlled trials (RCT), a meta-analysis of trials comparing ALND with observation suggests that a benefit exists.2

ALND has been the traditional means of staging the axilla in patients with breast cancer. However, since the advent of sentinel lymph node mapping, ALND is no longer the preferred staging procedure in patients with small, clinically node-negative breast cancer.3,4 The role of ALND in current practice is limited to women with locally advanced breast cancer and a subset of women with early breast cancer: in patients with clinically or radiologically apparent nodal disease at the time of presentation, in patients in whom a sentinel lymph node cannot be identified at the time of mapping, and in patients who have undergone a sentinel lymph node biopsy and were found to have an involved lymph node. The ACOSOG Z0011 trial was designed to study whether ALND after identification of a positive sentinel lymph node is associated with a survival benefit compared with observation alone.5 Its recent closure due to slow accrual ensures that ALND will continue to play a significant role in the management of patients with breast cancer.

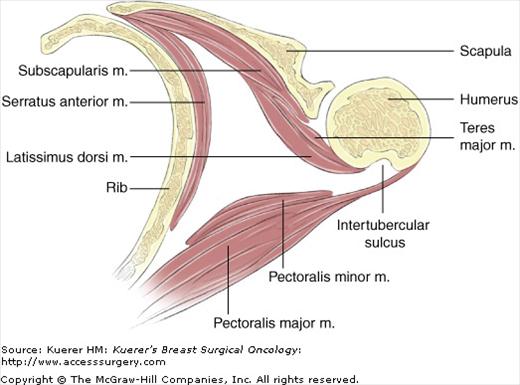

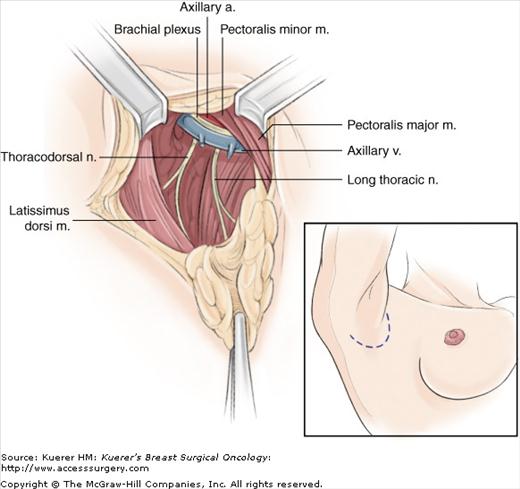

The axilla is a pyramidal-shaped space existing between the upper arm and thoracic chest wall and is bounded by the following structures: superiorly by the axillary vein; anteriorly by the pectoralis major and minor (encased within the clavipectoral fascia); posteriorly by the subscapularis, teres major, and scapular insert of the latissimus dorsi muscle; laterally by the latissimus dorsi muscle; and medially by the serratus anterior muscle and chest wall (Fig. 63-1). The apex of the triangle (the highest point of the axillary dissection) is the costoclavicular ligament or Halsted ligament.

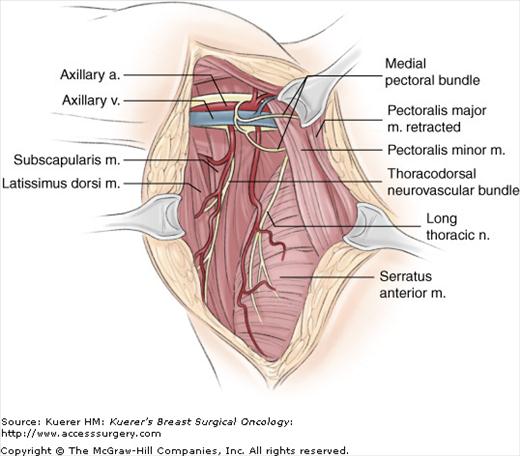

The long thoracic nerve arises from C5-7 and passes inferiorly on the lateral surface of the serratus anterior muscle, which it innervates. It is most commonly found within 1 cm of the chest wall, superficial to the investing fascia of serratus anterior muscle. Injury to the long thoracic nerve results in a “winged” scapula.

The thoracodorsal nerve arises from C6-8 and travels inferolaterally on the posterior axillary wall to supply the latissimus dorsi muscle. No obvious deficits are noticeable after transection of the thoracodorsal nerve.

The intercostobrachial nerve is the lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve combined with the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm. It travels transversely across the axilla after emerging from the second intercostal space. The intercostobrachial nerve supplies sensory innervation to the skin of the axilla and upper medial arm. It is trauma to this nerve that results in the commonly experienced sensory morbidity after axillary surgery.6-8

The medial pectoral nerve arises from C8 and T1 (medial cord of the brachial plexus) and enters the deep surface of the pectoralis minor muscle to supply the pectoralis minor and the lateral aspect of pectoralis major. It can often be identified sweeping around the lateral aspect of the pectoralis minor. Division of the medial pectoral nerve may result in muscle atrophy.

The lateral pectoral nerve arises from C5-7 (lateral cord of the brachial plexus) and supplies the pectoralis major muscle. It is seen medial to the pectoralis minor muscle as well as the medial pectoral nerve. Injury to this nerve would result in significant atrophy of the pectoralis major muscle.

The axillary artery originates medial to the pectoralis minor and crosses the axilla transversely. The second portion of the axillary artery, defined as posterior to the pectoralis minor, has 2 branches often identified during the course of an ALND, the thoracoacromial and long thoracic artery. Distal to these branches is the origination of the thoracodorsal artery, which is joined inferiorly by the thoracodorsal nerve. Axillary venous branches parallel the arterial anatomy.

By convention, the axillary lymph nodes are described in 3 levels, defined by the relationship to the pectoralis minor muscle. The level I nodes are found lateral to pectoralis minor. Level II is located posterior and level III medial to pectoralis minor on chest wall. Additional lymph nodes (called Rotter nodes) can be identified in the interpectoral (or Rotter) space, which is the space between the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

Langer arch is one of the more common congenital anomalies observed during an ALND and occurs in 5% of patients. It results from aberrant fibers of the latissimus dorsi muscle extending anteriorly and medially toward the pectoralis major muscle. Presence of a Langer arch may distort the typical axillary anatomy, and failure to recognize its presence may result in residual nodal tissue being left medial to the true latissimus dorsi insertion (the lateral border of the dissection). When identified, a Langer arch is handled by severing the aberrant muscle fibers at the level of lateral axillary vein.

The axillary vein may exist as a bifid or trifid vein. Early recognition and avoiding ligating structures traveling transversely in the axilla until the axillary vein is clearly delineated allows avoidance of injury.

Preoperative workup includes the standard preoperative clearance, including laboratory tests, chest radiograph, and electrocardiogram when indicated.

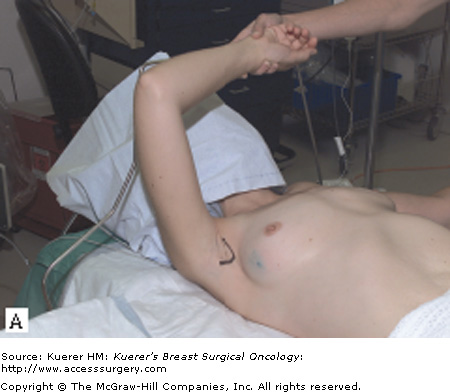

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the operative arm extended onto an arm board at 90° (Fig. 63-3). A U-shaped “ether screen” can be attached to the operating table prior to draping to allow positioning of the arm anterior to the patient during the procedure; positioning of the arm at a 90° angle above the table allows the pectoralis muscles to relax and provides better access into the medial aspects of the axilla. After induction of general anesthesia, a circumferential prep of the upper extremity, ipsilateral shoulder, and chest wall is performed. The arm board is draped with a Mayo stand cover, and the arm is covered with a free drape. Careful positioning to ensure that the arm is not abducted superiorly past 90° is critical to avoid placing stretch on the brachial plexus with a resultant plexopathy. The first assistant generally stands above the arm at the patient’s head.

Figure 63-3

Patient positioning (A) and draping (B). The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the operative arm extended onto an arm board at 90°; a U-shaped “ether screen” can be used to facilitate positioning of the arm anterior to the patient during the procedure. In cases where a mastectomy is being performed, the ALND is often performed through the mastectomy incision. In other circumstances, we prefer a curvilinear incision, placed just within or at the inferior margin of the hairline. © 2008 MSKCC

A single dose of a preoperative antibiotic with coverage of skin flora is administered prior to incision.

Several options are available for the axillary incision, based on the breast surgery planned and the body habitus. In cases where a mastectomy is being performed, the ALND is often performed through the mastectomy incision. In other circumstances, we prefer a curvilinear incision, placed just within or at the inferior margin of the hairline (Fig. 63-3); the incision should extend within the curve of the axilla from the pectoralis major to the medial border of the latissimus dorsi. This incision will be hidden when the woman is standing upright with her arms to her side and is most cosmetically acceptable because it will not be visible when wearing sleeveless tops. Furthermore, the curve provides a longer incision and therefore better exposure than a straight incision extending from the pectoral fold to the latissimus muscle.

After incision of the skin with a scalpel, skin flaps are created: laterally to the anterior border of latissimus, medially to the lateral aspect of the pectoralis muscle, superiorly to the approximate level of the axillary vein, and inferiorly to the fourth or fifth rib. Skin hooks, rakes, or Adair clamps are employed to facilitate retraction by the assisting surgeon. The operating surgeon applies countertension by retracting on the axillary fat with a laparotomy pad, and electrocautery is used to create flaps. The medial skin flaps will be naturally thinner if a concurrent mastectomy is performed to ensure complete removal of all breast tissue. However, flaps superiorly and laterally should be thicker because the primary goal of an ALND is to remove nodal tissue and not subcutaneous fat; no lymph nodes are present within the axilla superficial to axillary fascia.

After skin flaps have been circumferentially raised, the next step is to define the boundaries of the axilla. The lateral boundary is the latissimus dorsi muscle. When identifying the latissimus dorsi muscle, care should be taken to not dissect too superficially because one can easily pass the muscle posteriorly and may disrupt more sensory nerves. Similarly, dissection too medially can result in disruption of the serratus anterior fascia and potential injury to the long thoracic nerve. Medially, the lateral border of the pectoralis major and minor muscles are identified and delineated by incising the clavipectoral fascia. The medial pectoral bundle will be observed because it sweeps either laterally around or through pectoralis minor muscle and should be preserved if possible. The inferior border of the dissection should be inferior to the end of the axillary tail of the breast, typically the fourth or fifth rib, to ensure level I lymph nodes are not left behind. When defining the medial and inferior borders of the axilla, one should be aware of the position of the long thoracic nerve. In general, dissection can be performed anterior to the intercostobrachial nerve without danger of injury to the long thoracic nerve. Additionally, at the level of the fourth or fifth rib, the long thoracic nerve will have already entered the serratus anterior muscle.

At this point the axillary vein is approached. Most often when performing an ALND for breast cancer, a lateral approach to the axillary vein is performed. To identify the axillary vein, the latissimus dorsi muscle can be followed superiorly until it becomes tendinous; at this level, it passes posterior to the axillary vein prior to its insertion on the humerus. This marks the lateral boundary of the dissection. The axillary vein may also be identified medially. The medial position of the axillary vein can be estimated by extending an imaginary line in a horizontal course from the groove between the biceps and triceps muscle (when the arm is abducted) toward the medial pectoral bundle; the axillary vein will be found along this line.

Traditional teaching is that lymphedema risk is minimized if the lymphatic tissue on the superior aspect of the vein is preserved. Therefore, the inferior aspect of the axillary vein is skeletonized of lymphatic and fatty tissue, with care being taken to avoid including superior tissue as the specimen is retracted inferiorly. All inferiorly coursing superficial branches from the axillary vein are ligated, either with clips or ties, and sharply divided. The thoracoepigastric vein is the only named superficial branch on the axillary vein and should not be mistaken for the thoracodorsal vein, which enters more posteriorly.

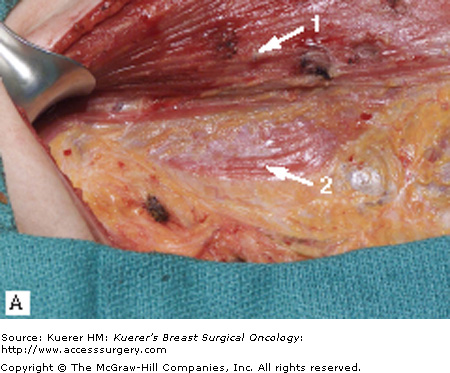

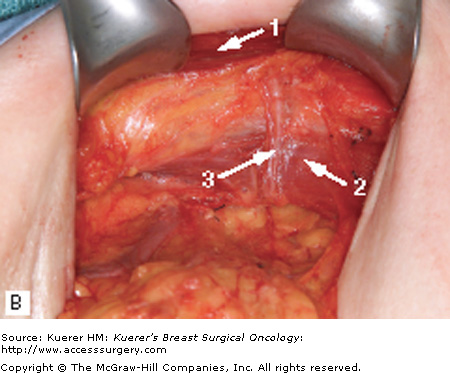

A Richardson retractor is used to retract the pectoralis major and minor muscles medially to allow access to the level II and III lymph nodes (Fig. 63-4). At this time, repositioning the arm into a 90° angle anterior to the patient will facilitate the dissection. The medial pectoral nerve will be visualized where it emerges just lateral to pectoralis minor. Lymphatic tissue on the chest wall is retracted inferolaterally as the dissection is continued along the inferior aspect of the axillary vein, clipping or tying any tissue of substance. At this time, the interpectoral (Rotter) space can be palpated and any identified nodes removed.

Figure 63-4

Relationship of the pectoralis major and minor muscles with the medial pectoral bundle. A. The lateral border of the pectoralis major (1) and minor (2) muscles is delineated by incising the clavipectoral fascia. B. A Richardson retractor is used to retract the pectoralis major and minor muscles medially. The medial pectoral nerve (3) will be visualized where it emerges just lateral to the pectoralis minor. 1, pectoralis major muscle; 2, pectoralis minor muscle; 3, medial pectoral bundle. (© 2008 MSKCC)

If necessary when mobilizing the level III nodes, the pectoralis minor muscle can be divided from its insertion on the coracoid process. If the pectoralis minor muscle is transected, great care should be taken to achieve hemostasis; small vessels within the muscle can retract and bleed later. To facilitate hemostasis, the superior portion of the pectoralis minor muscle at the level of the axillary vein can be clamped with a Kocher clamp and then the muscle divided inferior to the clamp with electrocautery. The Kocher clamp prevents retraction of vessels until hemostasis has been confirmed. When combined with a total mastectomy, the division of the pectoralis minor muscle has been labeled a “Patey” modified radical mastectomy, as compared with an “Auchincloss” modified radical mastectomy in which the pectoralis minor muscle is preserved. After level II and III lymph node tissue has been freed from the inferior aspect of the axillary vein, this tissue can be swept laterally into level I of the axilla, preparing the way for exposure of the long thoracic nerve.

The long thoracic nerve lies approximately 1 cm from the chest wall, deep in the axilla and superficial to the investing fascia of the serratus anterior muscle. Often it can be palpated as a “piano string” in the fatty tissue. Care should be taken to avoid dissecting the nerve away from the chest wall. Once identified, a blunt spread in a plane superficial and parallel to the nerve can dissect the nerve from the surrounding axillary tissue and place it back against the chest wall. The tissue lateral and inferior to the long thoracic nerve can be divided with careful protection of the nerve by the surgeon’s finger.

At this point, the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle is identified just lateral to the long thoracic nerve and deep to the thoracoepigastric vein. The remaining axillary tissue between the thoracodorsal and long thoracic nerves is then removed. With gentle inferior traction, a Kelly clamp can be carefully placed onto the residual tissue, after clear visualization of both nerves, and ligated. By sweeping bluntly with a sponge from superior to inferior, the axillary tissue anterior to the subscapularis muscle can then be cleared. Prior to this maneuver, ensure that the long thoracic nerve has been mobilized back to the chest wall and is separate from the axillary tissue (Fig. 63-5).

Figure 63-5

Identification of thoracodorsal nerve and long thoracic nerve. The remaining axillary tissue between the nerves is removed and axillary tissue swept inferiorly. For purposes of illustration, the contents of the axillary sheath are shown. (Reproduced, with permission, from Petrek JA, Blackwood MM. Axillary dissection: current practice and technique. Curr Prob Surg. 1995;32:285.)

The lateral aspect of the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle is then skeletonized. Small branches must be ligated or clipped. This is continued caudad until the nerve and vessels are seen to enter the latissimus dorsi muscle. A branch of the artery and vein turn medially to join the chest wall near the long thoracic nerve; these vessels can be preserved. The axillary specimen is then freed from the latissimus dorsi with electrocautery, and the specimen is passed from the table.

At the completion of the dissection, if clips were not used in the dissection of level II and III nodes, clips should be placed to mark the highest level of dissection (to assist in any necessary radiation treatment planning). Hemostasis is confirmed and a single closed suction drain placed. A skin closure with absorbable sutures is performed.

For most women, a dissection of the level I and II lymph nodes alone will provide accurate axillary staging. Fewer than 1% of women have metastases to level III lymph nodes without involvement of level II.9 Additionally, level III nodes are likely to be negative if the overall burden of disease in the axilla is low. Positive level III axillary nodes are found in only 2% of women with <3 positive axillary nodes and in 19% of women with 4 to 8 positive axillary nodes9; similarly, the probability of positive disease in the Rotter space is low. Therefore, a level I and II axillary dissection alone can be considered sufficient for most women unless the axillary nodal burden of disease is high or grossly palpable nodes in level III or Rotter space are present.

We place an axillary drain at the time of surgery, which remains in place until the output from the drain is <30 to 50 mL/24 hours. At our institution, we encourage range-of-motion activity starting on the first postoperative day.

Guidelines for the prevention of lymphedema in limbs at risk have been formulated (Table 63-1).10 Currently, little evidence-based literature addressing the prevention of postoperative lymphedema exists, and guideline recommendations are based on expert consensus. In the absence of data supporting or contradicting these recommendations, patient education regarding behavior following an ALND should follow these guidelines. Historically, avoidance of overuse of the at-risk extremity has been recommended. Two recent studies, one, a retrospective study of breast cancer survivors11 and the other, a RCT of weight training after axillary surgery,12 did not demonstrate an association between extremity use and lymphedema development. A recommendation for gradual build-up of activity with careful monitoring of the extremity seems reasonable given the findings of these new studies.

| I. Skin care: avoid trauma/infection to reduce infection risk |

| • Keep extremity clean and dry |

| • Pay attention to nail care; do not cut cuticles |

| • If possible, avoid punctures such as injections or blood draws |

| • Wear gloves while doing activity that may cause skin injury (dishes, gardening, etc.) |

| II. Activity/lifestyle |

| • Gradually build up the duration and intensity of any activity or exercise |

| • Monitor the extremity before and after activity for any change in size, shape, texture, soreness, heaviness, or firmness |

| • Maintain optimal weight |

| III. Avoid limb constriction |

| • If possible, avoid having blood pressure taken in at-risk limb |

| IV. Compression garments |

| • Support the at-risk limb during strenuous activity |

| • Consider wearing a well-fitting compression garment for air travel |

| V. Extremes of temperature |

| • Avoid exposure to extreme cold |

| • Avoid prolonged exposure to heat (particularly hot tubs or saunas) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree