Treatment of Obesity

Xavier Pi-Sunyer

The recommendation for treating obesity is based on two premises. The first is that weight can be lost and that, once lost, the lower weight can be maintained. The second is that this improves health. The evidence suggests that both of these are true (1,2). A loss of 10% of baseline weight can be achieved and maintained (2). But losing weight and particularly maintaining weight loss is very difficult and often discouraging, and the failure rate is high. Given our still-limited knowledge of the etiology of obesity, the primary emphasis must be on self-control, and the primary agent for change is the patient, not the physician. Motivation and commitment from the patient are required, but the support, understanding, and knowledge of the physician are also extremely helpful.

Because physicians are accustomed to pharmacologic solutions for most of the diseases they treat, they are not well attuned to the tedious task of slow, difficult weight loss, with its plateaus, relapses, and disappointing statistics. As a result, other health professionals have become involved in treatment. Dietitians, exercise physiologists, psychologists, social workers, and nurses advise and treat patients who want to lose weight. While these other professionals can be very helpful and often are more effective, a physician should monitor the weight-loss program and treat any other associated risk factors and health problems that are present or may develop.

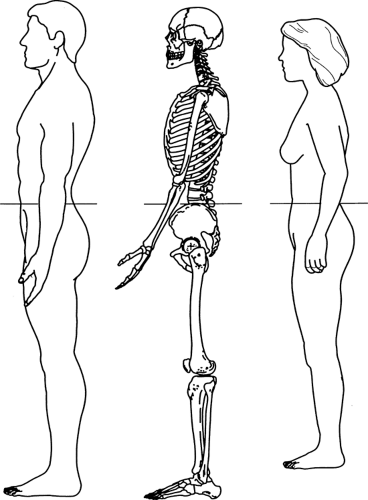

The assessment of obesity can be rapid and easy. A physician usually requires nothing more than a visual inspection to determine the need for weight loss. However, for a more quantitative assessment, there are simple techniques for categorizing and following a patient. The body mass index (BMI) is a useful guideline. It is calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared (kg/m2) (3). It can also be found from a table relating height and weight to BMI (Table 32.1). There is a fairly good correlation between BMI and body fat (4). However, this correlation is far from perfect, and very athletic persons can be misclassified due to their increased muscularity, although there are very few such disparities. Normal, overweight, and obese categories of BMI are shown in Table 32.2. The upper limit of the recommended BMI range is set at 25 because the mortality curve begins to increase at higher BMI values (5). There has been some argument that the BMI threshold should be set higher in some groups (women, older persons) and lower in others, such as Asians. However, the BMI of 25 is a reasonable and useful compromise (6), alerting individuals and populations to increased health risk.

TABLE 32.1. Body Mass Index Chara | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 32.2. Classification of Overweight and Obesity by Body-Mass Index, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Obesity aggravates or precipitates a number of other risk factors and diseases, including insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, thromboembolic disease, restrictive lung disease, sleep apnea, gout, degenerative arthritis, gallbladder disease, and infertility (7,8) (Table 32.3). In cases in which one or more of these conditions are present, more stringent standards of weight seem appropriate (9). Although the loss of weight is likely to ameliorate any associated conditions, therapy targeted specifically for these disorders is also often necessary.

TABLE 32.3. Diseases Associated with Obesity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The physician also needs to assess body-fat distribution. An excessive amount of fat in the trunk (central fat, upper-body fat) carries more health risk than does fat on the lower body (peripheral fat, lower-body fat). Central fat is independently associated with risk factors such as insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (10,11) and is an independent predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes (12,13,14,15). A simple assessment can be done by measuring waist circumference (Table 32.2). Measuring waist circumference is described in Figure 32.1.

Weight gain develops because energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. Once obesity supervenes, however, there may be a new weight stability, with caloric intake becoming equivalent once again to caloric expenditure. For a person to lose weight, energy intake must be decreased and/or energy expenditure increased to disequilibrate the energy balance equation and create a caloric deficit.

WEIGHT LOSS CAN IMPROVE HEALTH

Intentional weight loss in obese persons has been shown to improve health in both epidemiologic and clinical intervention studies. Williamson et al. (16) have shown that intentional weight loss decreases both cardiovascular and overall mortality. Weight loss also decreases morbidity (17).

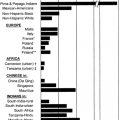

Short-term studies have demonstrated that weight loss resulting from low-calorie diets, very-low-calorie diets, anorectic drugs, or bypass surgery is associated with increased insulin sensitivity, improved insulin secretion by islet cells, decreased hepatic glucose production, and improved glucose disposal (1,18,19,20,21,22,23). Wing et al. (24) conducted a long-term study in which diabetic patients lost an average of 5.6 ± 4.0 kg during the active intervention phase and maintained a weight loss of 4.5 ± 7.5 kg at 1 year. Those who were most successful in losing weight had significant improvements in fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin values at 1 year even though they remained 20% above ideal body weight at the end of the study. Reductions in insulin dose or oral hypoglycemic medication were made for 100% of patients who lost 6.9 to 13.6 kg, 46% of those who lost 2.4% to 6.8 kg, and 40% of those who lost 0 to 2.3 kg. In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) study (25), the response to diet was studied in 3,044 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Their mean fasting plasma glucose level was 12.1 ± 3.7 mmol/L. The investigators determined that the weight loss needed to achieve normalization was 16% of ideal body weight in patients with initial fasting plasma glucose levels of 6 to 8 mmol/L, 21% in those with levels of 8 to 10 mmol/L, 28% in those with levels of 10 to 12 mmol/L, 35% in those with levels of 12 to 14 mmol/L, and 41% in those with levels greater than 14.0 mmol/L. At the 15-month assessment, 482 patients maintained normal fasting plasma glucose levels. On average, they had slightly lower fasting plasma glucose levels at study entry and had lost more weight than did other patients (25). After 3 months, 742 patients achieved normal fasting plasma glucose levels. However, it is important to remember that there will be nonresponders, and obese individuals who remain hyperglycemic after a weight loss of 2.3 to 9.1 kg are unlikely to improve with further weight loss and should be considered for treatment with hypoglycemic agents (26).

Weight loss through diet and exercise can reduce the risk of the conversion of impaired glucose tolerance to frank diabetes. This has been shown in studies in China (27), Finland (28), and the United States (29). In the Diabetes Prevention Program in the United States, which studied more than 4,000 patients over 5 years, the progression to diabetes was decreased by 58% (29).

Ross and Rissanen (30) have shown effects of diet and exercise on insulin sensitivity, preferential loss of visceral fat, and blood pressure. The effect of weight loss on hypertension has now been documented in a number of randomized clinical trials. Long-term studies have confirmed the effectiveness of weight reduction in lowering blood pressure and enabling some patients to become normotensive without the use of antihypertensive drugs and for others to reduce the dosage of required drugs or the number of drugs taken (31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42). The marked improvement found in many unmedicated hypertensive patients suggests that weight reduction should be the initial treatment for an obese person with hypertension. In patients for whom elimination of antihypertensive drugs is not a realistic goal, weight loss can potentiate the effects of drug therapy (40,41,43).

The dyslipidemia of obesity is characterized by high triglycerides, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and small dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles (44,45). With weight loss, triglycerides fall, HDL cholesterol rises, and small dense LDL particles become larger and less atherogenic (45). Short-term studies have confirmed the value of behavioral, low-calorie diet, and very-low-calorie diet interventions in decreasing total and LDL cholesterol levels and the HDL/LDL ratio and lowering triglyceride levels (46,47,48,49,50). Additional long-term studies, of greater than 1 year, have also been done and have shown a sustained improvement in the lipid profile of overweight and obese patients (33,36,51,52,53,54). Although some of these lipid changes are relatively small, they should not serve as a disincentive to embarking on a weight-loss program, because even modest improvements in lipid levels are associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease (1,17,55).

Few trials have explicitly addressed the relationship between weight loss and cardiovascular disease per se. A 10-year study of 2,500 patients from the Framingham Study cohort conducted by Higgins et al. (36) found a positive association between weight loss and cardiovascular disease, although this finding almost certainly results from the fact that the study does not distinguish disease-related involuntary weight loss from voluntary weight reduction.

Respiratory function is often impaired in obese individuals because of reduced lung volume, altered respiratory patterns, and decreased respiratory system compliance (7). Obesity-hyperventilation syndrome and sleep apnea are the most common respiratory disorders associated with severe obesity (8). Short-term studies of sleep apnea have indicated that weight loss resulting from low-calorie diets or gastric bypass surgery is associated with a marked reduction in apneic episodes and night awakenings and with a general improvement in sleep patterns (56,57,58,59,60,61).

Obesity is often associated with an increased risk of gout (62), as is increased central fat distribution (63). When persons lose weight, their uric acid levels may initially increase (1,64), but precipitation of gout by weight-loss therapy in asymptomatic patients is uncommon (65). Uric acid levels rarely become high enough to necessitate medical treatment (66). Occasionally, large amounts of uricosuria and a predisposition to renal uric acid stone formation occur. When the appropriate diagnosis is made, urine alkalinization is the treatment of choice.

Cross-sectional studies have repeatedly found an association between increasing weight and increased prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee (67,68,69) and, to a much lesser extent, of the hip (70). There have been just a few studies that have related weight reduction to the reduction of the onset of arthritis (71) or to the improvement of arthritic symptoms (72).

Obese persons are at a greater risk for developing gallstones than are persons of normal weight, probably because their bile is more highly saturated with cholesterol, their gallbladders are larger and less contractile, and their triglyceride levels tend to be higher (7). An association between loss of large amounts of weight and gallstone formation has been reported, although this finding has not been observed consistently (73,74,75,76). However, once individuals lose weight, their risk of gallstone formation and of cholecystitis decreases because the risk factors previously cited improve.

GOALS OF THERAPY

Obesity is associated with increased health risk, and this is especially so in patients with diabetes (80). The goals of therapy are to improve health risk. There are two ways to approach the

risk—one is to modify weight and the other is to focus on and try to modify other health-related variables (81). Focusing on other health-related variables can be done with individuals for whom the initiation of a weight-loss program seems impossible or impracticable.

risk—one is to modify weight and the other is to focus on and try to modify other health-related variables (81). Focusing on other health-related variables can be done with individuals for whom the initiation of a weight-loss program seems impossible or impracticable.

It is common for patients who are beginning a weight-loss program to have faulty and unrealistic beliefs about how much and how rapidly they can lose weight. It is important to counsel them in this regard to prevent disappointment and attrition.

Most obese persons wish to lose all of their excess weight and return to normal weight (82). While this may be realistic for someone whose BMI is close to normal (26 to 30), it is not realistic for individuals whose BMIs are higher. For these persons, a weight loss goal should be set for a reduction of 10% to 15% from their present baseline weight (2) for a number of reasons. First, it is very difficult for most persons to lose more than this, and it is consequently damaging for their self-image, sense of success, and satisfaction when they set goals that are unreasonable and generally unattainable. Second, if a patient is pushed to lose more, such as can occur with very-low-calorie (300 to 500 kcal) diets, experience has shown that, while persons can lose weight quickly, they will generally regain it almost as quickly (83).

BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

The traditional technique of handing a patient a printed description of a 1,200- or a 1,500-kcal diet, complete with specific menus and specific portion sizes, and telling him or her to increase exercise without further instruction, has generally been unsuccessful. With inadequate education and support, patients quickly abandon such programs and never increase their activity.

In an effort to prevent such failure, the use of behavioral therapy has increased. Approaches to changing behavior began with Ferster et al. (84) and were greatly popularized by Stuart (85). The goal of such therapy was to modify maladaptive eating by improving environmental control. The aim was to change eating behavior (86). This approach was found to be too narrow, and more recent adaptations have recognized obesity as much more complex than just maladaptive eating, with influences from genetic, physiologic, psychological, and social factors (87). The newer approaches have targeted not only eating but also physical activity. In the 1970s, cognitive-behavioral techniques were initiated (88,89,90). A number of psychologists have written about these treatment techniques (91,92,93,94,95).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree