Abstract

Transgender individuals have biological gender identities that differ from the sex recorded at birth. To proceed with medical therapy, a diagnosis of gender incongruence must be made. Although not all transgender patients desire medical intervention, hormone treatment and surgeries are available. Hormone therapy is safe, and appropriate screening for malignancy and adverse events should be considered. For adolescents, initial treatment includes puberty blockade before hormone therapy and surgery. These treatments can be destructive of fertility, thus preservation should always be discussed. Barriers to effective care for transgender patients exist, necessitating an increase in the number of knowledgeable transgender health care providers.

Key words

Gender identity, transgender, gender incongruence, hormonal therapy for transgender men and women, surgeries for transgender men and women, risk concerns and screening for malignancy, children and adolescents, fertility preservation, barriers to care, lack of transgender medical education

Introduction

- ◆

Gender identity is biological.

- ◆

Transgender individuals have gender identities that differ from the sex recorded at birth.

Gender identity is a person’s intrinsic sense of being male, female, or another gender. Transgender is an umbrella term that refers to individuals whose gender identities differ from the sex recorded at birth, which is usually based on external genitalia, whereas cisgender describes individuals whose gender identities align with their recorded sex at birth. Gender nonconformity and gender incongruence are terms similar in definition to transgender; both of these terms encompass the idea that gender identity and gender expression can appear as a spectrum as opposed to a dichotomy. Transsexual is an older term for gender nonconforming individuals who have changed their appearance in order to align with their gender identity, usually through hormonal therapy and/or gender-affirming surgeries ( Table 28.1 ). Studies estimate that 0.6% or 1.4 million adults in the United States identify as transgender.

| Gender identity | An individual’s innate sense of feeling male, female, neither, or some combination of both |

| Sex recorded at birth | Typically assigned according to external genitalia or chromosomes |

| Gender expression | How gender is presented to the outside world (i.e., feminine, masculine, androgynous); gender expression does not necessarily correlate with sex recorded at birth or gender identity |

| Gender nonconformity | Variation from the cultural norm in gender expression or gender role behavior (i.e., in choices of toys, playmates, etc.) |

| Transgender (“trans” as an abbreviation) | Umbrella term that is used to describe individuals with gender nonconformity; it includes individuals whose gender identity is different from their sex recorded at birth and/or whose gender expression does not fall within stereotypical definitions of masculinity and femininity; “transgender” is used as an adjective (“transgender people”), not a noun (“transgenders”) |

| Gender dysphoria or incongruence | Distress or discomfort that may occur when gender identity and sex recorded at birth are not completely congruent |

| Transsexual | Older, clinical term that has fallen out of favor; historically, it was used to refer to transgender people who sought medical or surgical interventions for gender affirmation |

| Sexual orientation | An individual’s pattern of physical and emotional arousal (including fantasies, activities, and behaviors) and the gender(s) of persons to whom an individual is physically or sexually attracted (gay/lesbian, straight, bisexual); sexual orientation is an entirely different construct than gender identity, but is often confused with it; the sexual orientation of transgender people is based upon their identified gender (i.e., a transgender man who is attracted to other men might identify as a gay man; a transgender woman who is attracted to other women might identify as a lesbian) |

| Sexual behaviors | Specific behaviors involving sexual activities that are useful for screening and risk assessment; many youth reject traditional labeling (homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual) but still have same-sex partners |

| Transgender man/transman | Person with a masculine gender identity whose sex recorded at birth was female |

| Transgender woman/transwoman | Person with a feminine gender identity whose sex recorded at birth was male |

| Genderqueer | Person of any sex recorded at birth who has a gender identity that is neither masculine or feminine, is some combination of the two, or is fluid |

Gender dysphoria is gender incongruence “associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” However, it is important to note that not every gender nonconforming individual experiences gender dysphoria. In other words, with the changing culture and the progress in medicine, only some gender nonconforming individuals experience significant gender dysphoria at some point in their lifetimes.

Additionally, as terminology is culture- and time-dependent and is rapidly evolving, it is important to use respectful language in different places and times, and among different people. While there are distinctions among the terms gender incongruence, gender nonconformity, transgender, and transsexual, any of these forms of expression may or may not be associated with gender dysphoria.

Gender identity is a durable, biological phenomenon. Strong evidence for the durable biological nature of gender identity includes the literature regarding 46,XY children with congenital anomalies who were raised as girls. In one study of 14 genetically XY children with cloacal exstrophy who were assigned female at birth, investigators found that all eight of the children who were aware of their XY chromosome pattern identified as male, including four who reported male gender identity even prior to learning about their chromosomal status. Two additional children assigned as male continued to identify as male. In a larger study of 46,XY children with penile agenesis, cloacal exstrophy, and penile ablation, investigators found that 15 of the 72 children assigned female at birth identified as male, and an additional 10 of the 72 children who continued to identify as female reported significant gender dysphoria. All of the children assigned male at birth continued to identify as male, except that one male child reported gender dysphoria.

In addition, studies of the brains of transgender individuals suggest a physical manifestation of gender identity. A postmortem study of six transgender women (male-to-female [MTF]) found that the size of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST) in the hypothalamus was within the female range. Examination of a transgender woman who did not undergo hormonal treatment also showed BST immunocytochemistry staining of somatostatin neurons within the female range. In addition, examination of one transgender man (female-to-male [FTM]) revealed a BST within the male range. These differences in BST staining were independent of sexual orientation and sex hormone treatment. Attempts to extend the cadaver finding with radiology include a positron emission tomography (PET) study measuring changes in regional cerebral blood flow using OH 2 O that found hormonally treated transgender women exhibited a pattern of hypothalamic activation that was intermediate between male and female when smelling certain steroids. Diffusion tensor imaging studies showed that hormonally untreated transgender men exhibited white matter microstructure more typically male than female, and untreated transgender women exhibited white matter microstructure that was intermediate between nontransgender male and female individuals used as controls.

Although these studies are small and there has not been a sexually dimorphic function attributed to these areas of the brain in humans, the studies are consistent with an organic nature to gender identity. While research to support the organic nature of gender identity is modest, there is no convincing literature that demonstrates an ability to externally change a person’s gender identity. Attempts to change gender identity rely on pressure to conform to sex norms, which only results in poor psychosocial outcomes.

Diagnosis

- ◆

Gender incongruence must be diagnosed before moving forward with medical therapy.

- ◆

Other medical and mental health disorders must be addressed before proceeding with treatment.

The diagnosis for gender incongruence must be made before moving forward with transgender hormone and surgical therapy. It is usually made by a qualified medical provider based on existing World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) or Endocrine Society guidelines. Complicating medical and mental health disorders should be addressed before treatment.

Criteria for Hormone Therapy

- 1.

Persistent incongruence between gender identity and external sexual anatomy at birth

- 2.

If significant medical or mental health concerns present, they must be stable.

- 3.

Capacity for fully informed consent and treatment

Hormonal Treatment for Transgender Individuals

- ◆

Exogenous testosterone is given to increase testosterone levels to the male range for transgender men.

- ◆

Estrogens and antiandrogens are given to reduce testosterone to the female range for transgender women.

Guidelines for the treatment of transgender patients represent a move toward more evidence-based treatment. The current broad strategy for hormone therapy for transgender patients includes (1) androgens to virilize transgender men and (2) estrogens, in addition to antiandrogens, to reduce testosterone levels to the conventional female range for transgender women while avoiding supra-physiologic levels (<200 pg/mL).

Mental health support is key to a good transgender health program. Patients should be screened for confounding mental health issues along with the patient’s ability to undergo hormone therapy. Although transgender individuals have a high incidence of mental health distress, it is often a result of social stigma, not gender incongruence.

Hormone Therapy for Transgender Men (Female-to-Male)

The hormonal treatment for transgender men is very similar to hormone replacement therapy for hypogonadal males in general. In order to achieve maximum virilization, testosterone levels should be increased to be within the normal male physiologic range (300 to 1000 ng/dL). Patients can anticipate cessation of menses, increased facial/body hair, male-pattern balding, increased acne, increased libido, increased muscle mass, clitoromegaly, and redistribution of fat within the first 3 to 12 months of testosterone therapy. Deepening of the voice may occur in many. The exact effects and time course of testosterone will vary from patient to patient.

When a patient begins hormone treatment, he can be started with half the dose used for a typical 70-kg man and then titrated quickly to achieve male physiologic serum levels (300 to 1000 ng/dL). Testosterone can be administered orally, transdermally, or parenterally, although no oral products are available in the United States ( Table 28.2 ). Testosterone enanthate or cypionate 50 to 200 mg weekly can be administered intramuscularly (IM) or subcutaneously (SQ). Higher doses (100 to 200 mg) can be administered every 2 weeks, but may result in more significant periodicity in testosterone levels. Transdermal preparations, such as testosterone gel (25 to 100 mg/day) or testosterone patch (25 to 75 mg/day), will achieve the same virilizing effects as IM testosterone, but the patch may cause skin irritation. Although transdermal preparations may result in smoother testosterone levels, it may be harder to achieve desired levels with them. Oral testosterone undecanoate (160 to 240 mg/day), and testosterone undecanoate IM (1000 mg every 12 weeks) have not been available in the United States.

| Monitoring for Transgender Men (FTM) on Hormone Therapy |

|

| Hormone Regimens for Transgender Men |

|

| Adverse Effects of Androgen Supplementation |

| Likely Increased Risk |

|

| Possible Increased Risk |

|

| Possible Increased Risk with Presence of Additional Risk Factors |

|

| No Increased Risk or Inconclusive |

|

Patients taking testosterone should be monitored for both virilizing and adverse effects every 3 months for the first year and then every 6 to 12 months ( Table 28.2 ).

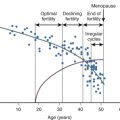

Serum testosterone levels should be monitored until stability is achieved within the male range. Patients taking testosterone enanthate or cypionate IM or SQ can have testosterone peak levels measured 24 to 48 hours after injections, and occasional trough levels measured immediately prior to injections. Patients taking testosterone transdermally can have levels sampled at any time after 1 week. Androgen-sensitive indices, such as hematocrit (or hemoglobin) and a lipid profile, should be monitored at follow-up visits. Adequate levels of sex hormones are required to maintain bone mass, thus transgender men at risk for osteoporosis should have bone mineral density (BMD) measured before initiating testosterone. Otherwise, BMD screening can be initiated at age 60 or if testosterone levels are consistently low. Transgender men with cervixes or breast tissue should be screened accordingly.

Testosterone therapy should not be initiated in patients who are pregnant, have unstable coronary artery disease, or untreated polycythemia (hematocrit at or above 55%). Testosterone therapy may unmask polycythemia and hyperlipidemia, which should be treated appropriately. It is unknown if testosterone therapy puts transgender men at an increased risk for uterine or ovarian cancer, so despite the absence of data, a hysterectomy has been encouraged in some protocols.

Testosterone is known to stimulate erythropoiesis; therefore, monitoring to ensure that hematocrit levels are less than 55% is necessary for transgender men. Although current data support the safety of transgender hormone therapy, more long-term studies are needed in this area.

Hormone Therapy for Transgender Women (Male-to-Female)

The hormonal treatment for transgender women is only slightly more complicated than the regimen for transgender men. In order to achieve maximum feminization, transgender women with testes often require an antiandrogen in addition to estrogen. The goal in hormone therapy for transgender women is to decrease testosterone to the female range (<100 ng/dL) without supra-physiologic levels of estradiol (<200 pg/mL). There are no specific physical endpoints to monitor. Rather, monitoring consists of checking hormone levels and providing surveillance for cancers in existing tissues. While the effects and time course of estrogen and antiandrogen therapy vary, patients can expect decreased facial/body hair, decreased libido, decreased spontaneous erections, decreased skin oiliness, decreased muscle mass, redistribution of fat, and breast development within the first 3 to 12 months. Breast growth will usually peak after 2 years of hormone therapy.

Incorporating an antiandrogen into the paradigm for transwomen allows for lower doses of estrogen ( Table 28.3 ). Spironolactone is the most commonly prescribed and least costly antiandrogen used in the United States. It is an aldosterone receptor antagonist that has been shown to decrease mortality in patients with New York Heart Association class 3 and greater congestive heart failure. Spironolactone also inhibits the secretion and activity of testosterone (although the mechanism is not known).