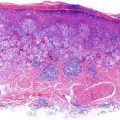

Figure 11.1

Box shows area of application of Aldara for s BCC

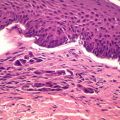

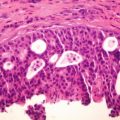

Histological report is detailed above – which reveals a non-ulcerated tumor of 0.8 mm Breslow thickness, Clark Level 3 invasive melanoma, arising in an area of melanoma-in-situ. A compete skin and lymph node examination revealed no other abnormalities. After reviewing the histopathology, this patient was managed with a wide local excision with 1 cm margins in keeping with standard guidelines for management of Stage 1A melanoma of skin.

Discussion

Dermatologists, surgeons and skin cancer doctors are faced with an epidemic of skin cancer in Australia and New Zealand. Actinic Keratoses and Squamous Cell Carcinomas share multiple genomic mutations that suggest common origins [24]. It is well known that increases in p53 mutations are seen in sun-damaged skin, AK, and SCC [25]. Given the need to reduce unnecessary surgery as well as associated costs, researchers have turned their focus to topical applications to deal with skin cancer. Some prevailing topical treatments include 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac sodium, topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) with 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) Imiquimod and few others discussed earlier.

Given the clinical interest for TLR agonists in metastatic melanoma and indeed skin cancer, it is essential to determine the mechanism of action of Imidazoquinolines such as Imiquimod. Imiquimod has many cellular effects that stimulate Th-1 innate immunity. The drug’s effects is mediated after binding to TLR 7, the receptor that is found on dendritic cells and monocytes. TLR-7 is also involved in regulation of cellular apoptosis. Following Imiquimod treatment, ‘immunologic memory’ is established, and this differentiates this drug from other topical agents [26]. From Imiquimod’s early use for genital warts, it was noted that a significant proportion of patients ended up ‘non-responders.’

Some authors have been enthusiastic about the ‘field clearance’ effects of Imiquimod – the concept of lymphatic transport of immune cells and factors with subsequent immunological curing of tumors, not only in the treated area, but also those in ‘field’ around the treatment site. Akkilic-Materna and colleagues suggest that their observations on the actions of Imiquimod support the concept of lymphatic transport of immune cells and factors with subsequent immunological curing of tumors, not only in the treated area, but also those in the area between the imiquimod application site and the regional lymph nodes – what they term the “lymphatic field clearance” [27] Others have raised concerns about recurrence after Imiquimod use and whether Imiquimod may select more aggressive tumor cells or may just convey a natural course of tumor recurrence as we see with other treatment modalities [28].

Recurrence aside, there have been several reports of Imiquimod triggering keratoacanthomas and indeed infiltrating or aggressive SCC [29]. There has been also a report of a pulmonary embolism occurring after Imiquimod use [30]. The exact mechanism of inducing tumors remains unknown, although the exuberant immunological response is blamed – a sort of fighting ‘fire with fire’ when utilizing immune-modulating agents that stimulate apoptosis.

There are now several reports that have supported the use of Imiquimod in amelanotic lentigo maligna [31], peri-ocular lentigo maligna [32], facial lentigo maligna [33] and even in large lentigo malignas prior to staged excision [34]. However given the reports of Imiquimod causing aggressive SCC, or in our case, an invasive melanoma arising at the site of topical Imiquimod use, I would like to stress the importance of follow up after Imiquimod use.

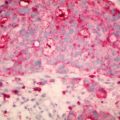

Schön and others have discussed that more pleiotrophic antitumoral responses have to be considered when studying imidazoquinolines. They demonstrated that imiquimod is able to act not only as synthetic adjuvant but also as direct inducer of apoptosis for melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. They concluded that cell death was exerted by apoptosis rather than necrosis and that this pro-apoptotic signal is selectively activated in melanoma cells, but not in primary human melanocytes [35].

Of course, in this case report, it is impossible to prove causal effect – other than to say that the melanoma arose at the exact Imiquimod treatment site. However, I believe it is prudent, given this case-study, to undertake ongoing surveillance of patients after Imiquimod use.

References

1.

2.

3.

Klein E, Milgrom H, Helm F, Ambrus J, Traenkle HL, Stoll HL. Tumors of the skin: effects of local use of cytostatic agents. Skin (Los Angeles). 1962;1:81–7.

4.

Maltusch A, Rowert-Huber J, Matthies C, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Stockfleth E. Modes of action of diclofenac 3 %/hyaluronic acid 2.5 % in the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1011–7.PubMed

5.

Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, Melgaard A, Xu Z, Berman B. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010–9.CrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree