Summary of Key Points

- •

Smoking is the predominant risk factor for development of lung cancer. As tobacco is introduced to societies, common patterns emerge. Typically, it is first used in men, then later in women. A 20- to 25-year lag between smoking rates and lung cancer rates reflects this.

- •

The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) provides a comprehensive global tobacco-control strategy. Six key concepts are described with the mnemonic “MPOWER.”

- •

M onitor Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies: The WHO has standardized surveys and metrics to make comparisons possible between societies and over time.

- •

P rotect People from Tobacco Smoke: Secondhand smoke is a risk factor for lung cancer. Implementation of public smoking bans has been linked to decreased disease from tobacco smoke (asthma exacerbations, acute coronary events, etc.).

- •

O ffer to Help Quit Tobacco Use: Physician advice, pharmacotherapy, and tobacco quitlines improve cessation rates, but are underutilized.

- •

W arn About the Dangers of Tobacco: Public service messages are effective. Written and graphic warning labels on tobacco packages reach each user and are effective at decreasing use.

- •

E nforce Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorships: Often tobacco marketing targets youth and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Restricting marketing prevents initiation and decreases use.

- •

R aise Taxes: Taxation suppresses use while raising money; unfortunately, most tobacco tax funds do not support other tobacco-control measures.

- •

Many lives have been saved by tobacco control over the past 50 years. However, due to ongoing use of tobacco, millions of preventable deaths have occurred. Tobacco use has steadily grown and spread across the globe to such a degree that tobacco-induced death and disability have attained epidemic proportions. Many diseases and conditions attributable to smoking, such as cerebrovascular disease, heart disease, emphysema, and cancer—especially lung cancer—have led to death and disability. This chapter highlights the growth, spread, and current status of the tobacco epidemic worldwide; global efforts to curb the use of tobacco; and the potential impact of control measures on outcomes, specifically lung cancer–related mortality.

As tobacco use is encouraged, promoted, and perpetuated with a variety of mechanisms, there is a need to intervene and provide tobacco prevention and cessation in multiple dimensions. Various tobacco-control strategies have been used in the past, with varying degrees of success across different populations. The WHO FCTC provides a unified multidimensional approach to tobacco control for the 21st century, with a structure to discuss implementation of comprehensive tobacco control. Although societies around the globe differ widely in terms of language, cultural norms, economic resources, and smoking rates, nearly all societies are afflicted with the tobacco epidemic, and a concerted effort involving the use of evidence-based strategies has the potential to save millions of lives.

Historical Context of the Tobacco Epidemic

Tobacco is indigenous to the Americas, and, prior to its European discovery in 1492, tobacco was unknown in the rest of the world. After Europeans were introduced to tobacco—and nicotine addiction—consumption steadily grew in Europe. Despite its popularity, King James I of England issued “A Counterblaste to Tobacco” as one of the first documented efforts of tobacco control. In 1604, he not only stated the harm to the smoker as being “… hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs …” but also discussed the implications of second-hand smoke in the context of a woman whose husband smokes and “resolve[s] to live in a perpetuall stinking torment.” One of the first documented tobacco-control policies was his accompanying “Commissio pro Tabacco,” which levied a tax on tobacco importation. In these early years of the spread of tobacco, much of its use was in the form of chew tobacco, pipe tobacco, cigars, or snuff. Tobacco was even touted as medicinal. Despite the proclamation from King James I, government taxation, and various religious edicts, tobacco use continued to grow throughout Europe.

The Industrial Revolution included the development of cigarette-rolling machines in the late 1800s, which not only spawned mass production and increased the use of tobacco but also shifted the bulk of tobacco use to cigarette smoking. Cigarettes are smoked with deeper inhalation than pipe tobacco or cigars, leading to absorption in the pulmonary parenchyma rather than in buccal and pharyngeal parenchyma. As a result of pulmonary delivery, a much more rapid and intense peak in nicotine levels leads to a greater addiction potential. This more addictive product, combined with industrialization, global transportation, and aggressive marketing to men, women, and children across the globe, led to an explosion in tobacco use and a highly profitable industry.

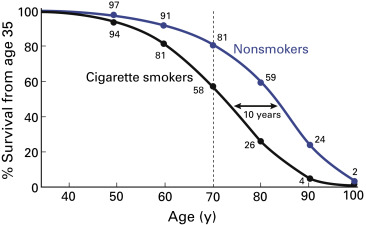

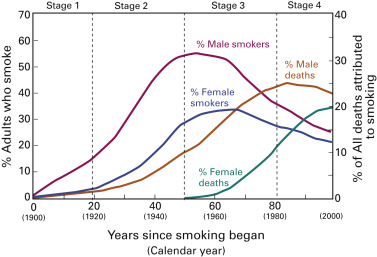

The epidemiologic relationship between smoking rates in a population and death rates attributable to smoking has been extensively analyzed on a global scale, and fascinating patterns tend to recur predictably from one society to another. Lopez et al. noted that the rise in the prevalence of cigarette smoking was reflected in the rise in the death rate caused by smoking-related illnesses, with an approximately 20-year to 25-year lag. Overall, it has been demonstrated that death rates from tobacco-induced disease occur at a rate of roughly half of the smoking rate, given this time lag (e.g., for a population with a 60% smoking rate, 30% of the deaths 20 years later are secondary to smoking). Stage I of a smoking epidemic represents initiation, with low smoking rates and very low death rates due to smoking ( Fig. 2.1 ). Stage II consists of a rapid rise in the smoking prevalence among men to its peak, with the beginning of a rise in deaths. During this time, smoking among women just starts to increase, but there are few deaths. Stage III consists of a decline in smoking among men, with a continued increase in smoking among women. During this time, the death rate among men continues to rise following the 20-year to 25-year lag from the peak in smoking, and the death rate among women also begins to increase. Stage IV consists of a decline in smoking rates among men and a plateau or fall in smoking rates among women, with an eventual decline in death rates. The Lopez model has been applied to many societies, and, in general, developing nations tend to be represented by stages I and II, whereas many industrialized nations have experienced their peak in smoking rates and deaths, particularly among men, and are in stages III or IV.

This rise and fall in the number of smoking-related deaths closely parallels the rise and fall in lung cancer incidence and mortality rates in the United States. Smoking was relatively uncommon before 1900, correlating with Lopez stage I. The smoking rate among men in the United States increased from the 1900s and peaked around 1965 (stage II). After the Surgeon General’s report of the link between smoking and cancer, smoking rates among men decreased, yet smoking-related deaths among men continued to increase (stage III). This increase in male smoking prevalence eventually led to a peak and decrease in lung cancer–related deaths among men approximately 20 years later. During this time, the smoking rate among women rose and plateaued. In the late 1990s and beyond, the death rate among women was just beginning to decrease (stage IV). According to the Lopez model, the incidence of lung cancer and lung cancer–related mortality should continue to fall for men and women in the United States as smoking rates have declined.

This descriptive model has also been applied to many other societies. Rates of smoking in China and Japan have risen for men, and the rates of smoking-attributable deaths continue to rise in these societies (stage II). However, countries such as Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Sweden have progressed through all phases of the Lopez model and are in stage IV, with declining rates of smoking-related deaths among men and women. Despite the decrease in tobacco use in some of the aforementioned countries, tobacco use is growing in other countries, particularly India, Japan, and China, where societal and cultural shifts are leading to growing numbers of people who smoke, particularly women. The growth of the global population, the spread of tobacco use to more countries, and the rising rates of smoking among women are all contributing to a projected rapid global increase in tobacco use and tobacco-induced deaths. The toll of tobacco is considerable, with an estimated 100 million deaths globally in the 20th century; currently, 5 million deaths are reported annually, with 1 billion deaths projected globally in the 21st century if the trajectory is not changed.

As smoking rates have declined in some countries, they have stabilized or increased in other countries as a result of aggressive marketing by the tobacco industry and lax or nonexistent tobacco-control policies. With the irrefutable evidence that this aggressively marketed, addictive product leads to premature death and disability among people who smoke (with one in two people who continue to smoke dying of tobacco-related disease) and illness in people exposed to secondhand smoke, tobacco control not only can be seen as a public health crisis but also can be viewed from ethical and human rights perspectives. By the end of the 20th century, the tobacco epidemic had steadily grown into a massive global crisis in which, currently, 5 million people die annually as a result of its use. Attempts at tobacco control have varied among different countries, and often by state or province within a country. The production, marketing, and distribution of cigarettes are predominantly controlled by a few international corporations: Philip Morris, Altria, British American Tobacco, Japan Tobacco, R. J. Reynolds, and China National Tobacco. The production, marketing, and distribution of cigarettes had become a globally organized network, and although the battle was being fought on many fronts, there was no global consensus on measures of tobacco control, and unified countermeasures to combat this problem were lacking.

21st Century Tobacco-Control Measures

The need for a comprehensive, unified, and enforceable global strategy to combat this global epidemic was initially conceptualized by Roemer and Taylor in 1993. These authors subsequently presented a strategy for a FCTC to the WHO in 1995. Persistent efforts led to adoption of the WHO FCTC at the World Health Assembly in 2003. The WHO FCTC came into force in 2005 as the first international treaty adopted under the WHO and was ratified by 177 parties in 2013. The United States notably remains a nonparty. This unprecedented agreement between party nations became the first international legal instrument for a unified approach to combat the global tobacco epidemic. The multidimensional treaty delineates universal standards declaring the dangers of tobacco and outlines strategies for limiting its use worldwide through provisions regarding education, production, advertisement, distribution, sale, and taxation.

The details of the entire WHO FCTC are beyond the scope of this chapter, but the WHO produced an internationally applicable summary of the essential elements of a tobacco-control strategy, publicized as the mnemonic “MPOWER,” which includes six components ( Table 2.1 ). Examples of successful tobacco-control strategies are discussed here using these categories as a construct.

|

Monitor Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies

If an epidemic is to be treated, it must first be measured. It is crucial to dramatically improve global surveillance of tobacco use among adults and youths. Until recently, the extent of the epidemic has not been well documented, particularly in developing countries. Differences among nations with regard to the tools that have been used to measure this epidemic have made comparisons difficult. The WHO Global Tobacco Surveillance System is a uniform comprehensive format for measuring the epidemic and gauging the impact of measures when implemented. The system comprises three school-based components (the Global Youth Tobacco Survey, the Global School Personnel Survey, and the Global Health Professions Student Survey) and one adult component (the Global Adult Tobacco Survey). These surveys contain the same basic data fields in all queries, and individual countries can add other specific points if they wish. Uniformity is necessary to compare one society and/or time point with another. The system involves three sequential phases: a survey workshop, data analysis, and a programmatic workshop that is designed to determine the needs and priorities to suit that area at that time. The surveys are intended to be conducted shortly after the implementation of control measures and then repeated every few years. Monitoring with reliable tools to obtain accurate data is the only way to truly determine where tobacco control is most needed, what type of tobacco control is most appropriate, who the target audience should be, and the outcomes of any implemented policies.

Protect People From Tobacco Smoke

The harm that smoking causes to people who smoke has been a driving force for tobacco control, but the effects of smoking on nonsmokers has led to another arm of tobacco control: protecting all people from tobacco smoke. Secondhand smoke, also known as environmental tobacco smoke or passive smoking, is a risk factor for asthma, bronchitis, and respiratory infections and also has been demonstrated to be a risk for the development of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. Rates of lung cancer are higher for women who have never smoked but have husbands who smoke, with a relative risk ranging from 1.3 to 3.5. Rates are higher for women with husbands who are “heavy” smokers (>20 cigarettes per day), suggesting a dose–response relationship.

Mackay et al. and Pell et al. reported on the effect of a 2006 policy to prohibit smoking in all enclosed places in Scotland on health conditions related to secondhand smoke. In analyzing hospital data, the authors found that the rate of hospitalizations for childhood asthma was increasing 5.2% per year before the policy and fell by 18.2% per year after the policy took effect; this change was noted for both preschool and school-age children. In addition, after implementation of the policy, the rate of admissions for acute coronary syndrome decreased by 14% among active smokers, by 19% among former smokers, and by 21% among individuals who had never smoked. When the 12-month periods before and after implementation of the policy were compared, the rate of admissions for acute coronary syndrome fell by 17%. In comparison, during that time in England (where there were no smoke-free laws), the rate fell by only 4%, and during the preceding decade in Scotland, the rate decreased by an average of 3% per year. Serum cotinine was measured in patients during this time. The self-reported exposure to secondhand smoke decreased among nonsmokers, and this decrease was validated on the basis of lower cotinine levels in those individuals. Many other examples demonstrate the impact of smoke-free laws on public health, and it is not surprising that improved outcomes are seen among nonsmokers, but it is encouraging that improved outcomes can be found among smokers as well, likely as a result of a reduction in tobacco use despite the fact that they are still smoking.

Offer Help to Quit Tobacco Use

Many people who use tobacco may not actively seek assistance with cessation because of either a lack of interest in quitting, the perceived futility of cessation efforts, the stigma associated with tobacco use, or a lack of willingness to invest the time and financial resources to support their desire to quit. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer conducted a survey regarding the smoking-cessation practices among its members (response rate, 40.5%). According to the survey, 90% of respondents believe that current smoking affects clinical outcomes and that cessation should be a standard part of care; 90% ask their patients about smoking at the time of the initial visit; 81% advise their patients to quit (but only 40% discuss pharmacotherapy); and 39% provide cessation assistance. These survey results likely represent a best-case scenario for cancer providers, as the respondents were members of an international multidisciplinary lung cancer organization who were motivated to respond to the survey and because the survey responses were self-reported. By contrast, the rates of primary physician queries about smoking and advice on cessation have been disappointingly low, likely driven by the perceived of lack of efficacy of such efforts among practitioners.

However, although many people who smoke may not quit on the basis of their physician’s advice, brief counseling from primary physicians at every visit could have a substantial impact. In one of the first landmark studies on this subject, published in 1979, researchers from London found that physician practices such as asking patients about tobacco use, advising patients to stop smoking, providing informational pamphlets, and telling patients they will be called for follow-up yielded a 5.1% quit rate at 1 year. Although this quit rate was modest, it was significantly higher than the rate for the control group (0.3%; p < 0.001). This finding suggests that active cessation interventions by primary care physicians could substantially impact the number of people who would quit. Unfortunately, as yet, primary care providers often do not follow the most basic steps of asking patients about smoking, advising them to stop smoking, and referring them to a cessation service such as a telephone quitline or other resource.

In many countries, quitlines are able to offer assistance with cessation. In the United States, many, but not all, of the quitlines run by individual states provide pharmacotherapy such as nicotine-replacement therapy. However, most countries are not able to afford this type of intervention. For many people who smoke, the cost of the nicotine-replacement therapy can exceed the cost of cigarettes. The convenience of the quitline, the availability of nicotine-replacement therapy, and the free-of-charge service would lead one to think that quitlines are popular, but the penetrance of quitlines is low, even in developed countries. For example, Australia has extremely aggressive and successful tobacco-control programs, with the quitline number displayed in all retail outlets, on every package of cigarettes, and in advertisements as part of a mass media campaign, yet one study demonstrated that only 3.6% of people who smoke used the service in 1 year, suggesting that many people who smoke may not initiate the call for help in quitting and may not be interested in asking for help.

Compared with face-to-face counseling with a physician or other health-care provider, quitlines are more convenient, less costly, and more easily approached by reluctant smokers. A cost analysis of a national quitline in Sweden demonstrated a 31% self-reported 1-year quit rate with an estimated cost of $1052 to $1360 per quitter and of $311 to $401 per life year saved, indicating that the quitline was less costly than other modalities that were analyzed, such as counseling by a general practitioner, a community mass media campaign, and bupropion treatment.

Warn About the Dangers of Tobacco

Education regarding the addictive and harmful nature of smoking can be delivered in multiple ways, including (but not limited to) physician–patient interactions, education in schools, public announcements on television and radio, warning labels on cigarettes, and print and outdoor advertisements related to the effects of tobacco. One of the simplest and least expensive ways to distribute education about tobacco is through mandatory warning labels on tobacco packaging. A 2006 study conducted in four countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada) demonstrated that larger warnings and graphic warnings were more effective for communicating the risks of smoking compared with the very inconspicuous United States warnings. Another report on warnings in these same countries was published in 2009, after the use of graphic warnings had been implemented in Australia. The impact of health warnings was evaluated by comparing graphic warnings from Australia and Canada with text-only warnings from the United Kingdom and the United States. The new graphic warnings in Australia increased smokers’ salience (reading and noticing), cognitive reactions (thinking about harm and quitting), and behavioral responses (forgoing cigarettes and avoiding the warnings).

Clearly, graphic warning labels are important means of communication in areas with lower literacy rates, but, even for populations with higher literacy rates, the graphic labels have greater impact and are associated with lower smoking rates. While public media campaigns and advertisements that warn about the dangers of tobacco have been shown to be effective, they do require financial resources for the creation and distribution of the messages and ongoing funding for maintenance. The implementation of policies regarding enlarging warning labels and including graphic warnings does not require ongoing cost to the government and literally puts an effective warning message in the hands of every tobacco user.

Enforce Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship

The tobacco industry spends tens of billions of dollars annually to promote its product, which in turn kills up to half of its users. The industry depends on promotion to maintain its current customer base and to recruit “replacement smokers,” that is, to replace the minority of smokers who successfully quit and the masses who die of tobacco-related diseases. An Article of the WHO FCTC states that all parties must implement comprehensive restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship within 5 years. In many countries, particularly those with developing economies, tobacco use among women traditionally has not been high and women are viewed as a growth market by industry because of growing financial and social independence. It is unsurprising that women and minors have been the targets of many tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship activities, with the rate of smoking among women expected to double between 2005 and 2025. Because of this selective targeting, tobacco control also needs to be gender and age based in its approach. Exposure to tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship is associated with a higher prevalence of smoking, and a comprehensive ban on such activities leads to lower exposure to these messages, a finding that has held true across different socioeconomic groups. Bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship have been shown to decrease smoking rates in both developed and developing countries.

Raise Taxes on Tobacco

“Of all the concerns, there is one—taxation—that alarms us the most. While marketing restrictions and [restrictions on] public and passive smoking do depress volume, in our experience taxation depresses it much more severely.”

These words from the tobacco industry, written more than 25 years ago, still hold true today. A 10% rise in retail price will result in a 4% decrease in cigarette sales through both increased cessation and reduced consumption by active smokers in developed nations and in an estimated 8% decrease in middle- to lower-income countries. The fact that tobacco disproportionately affects lower socioeconomic groups that are linked with a greater elasticity (i.e., reduced sales with increased price) makes increasing the cost a logical tobacco-control strategy, particularly with respect to these lower socioeconomic groups. While some tobacco-control policies (e.g., media campaigns and cessation-support services) require ongoing financial resources and others (e.g., clean indoor air policies and policies banning advertisement) are fairly inexpensive to implement, taxation has the unique ability to effectively suppress tobacco use and generate revenue. Unfortunately, of the $133 billion globally generated by tobacco taxation, less than 1% of revenues collected in tobacco taxes are reinvested in prevention or cessation efforts. A progressive approach to tobacco taxation was implemented in Costa Rica in 2012, with a rise in tobacco taxes of approximately $0.80 per pack. This change increased total taxes from approximately 56% to 71% of the cost of a pack of cigarettes, and all of the new tax revenue was earmarked for cancer treatment, tobacco-prevention and cessation services and research, support of the nation’s Health Promotion Act, and other health-related measures. Although not all of these measures are directly related to tobacco control, some of the increased funds will directly benefit prevention, cessation, treatment, and patient-support efforts. A provision of this act is that taxes will automatically increase annually to keep pace with inflation. Taxes passed as a flat tax amount per quantity of tobacco will be eroded by inflation over time unless levied as a percentage of the price or adjusted for inflation.

Combinations of Measures

Typically, successful tobacco control is implemented not as a single measure but rather as part of a more comprehensive multifaceted approach involving several of the aforementioned concepts; therefore it may be difficult to distill the impact of one measure on smoking rates when several are implemented in combination. For example, in California, clean indoor air legislation was accompanied by increased tax and antitobacco advertising. This combination resulted not only in a lower smoking prevalence but also lower per capita cigarette consumption. Reducing smoking is the aim of these programs, but the deeper overall goal is to improve public health, and therefore outcomes such as the lower mortality from heart disease and the decreased rates of bladder cancer and lung cancer that were found following the implementation of the California comprehensive tobacco program further strengthen the need for multidimensional tobacco-control programs.

Some of the strongest tobacco-control measures that have an impact on several of the aforementioned categories have been developed in Australia. For example, the implementation of plain packaging regulations in Australia acts in several dimensions by providing health warnings and the quitline number while also eliminating brand image and advertising and promotion on the packaging itself. This approach not only has resulted in the distribution of warnings and the promotion of quitlines but has also been shown to decrease the appeal of smoking and to increase thoughts about quitting.

Impact of Tobacco Control on Lung Cancer Mortality

As described in the previous section, effective tobacco-control efforts have been well defined and have a strong evidence base. The MPOWER strategy was developed by the WHO to assist countries in implementing the FCTC. The impact of tobacco-control efforts on the incidence of and mortality resulting from lung cancer is demonstrated by the Lopez curves describing the stages of the smoking epidemic and the consequent epidemic of lung cancer ( Fig. 2.1 ). Unfortunately, only a few of the more economically developed countries heeded the epidemiologic news from the 1950s that smoking causes lung cancer.

Doll et al. demonstrated significantly improved survival for British male physicians who were nonsmokers ( Fig. 2.2 ) and also significant benefits for physicians who had smoked but quit. Predominantly because of this cessation, Britain was also the first country to have a drop in lung cancer rates among men ( Fig. 2.3 ). Australia and the United States were close behind, but, interestingly, the decline was slower. Unfortunately, the lung cancer rates among women do not replicate the rates among men in different countries because of the variety of cultural influences on smoking prevalence. These changes in the United States and the United Kingdom were primarily driven by smoking cessation as a result of epidemiologic evidence linking disease to smoking. In the United States, the peak prevalence of male smokers started to decline after the 1930 birth cohort as a result of smoking cessation ( Fig. 2.4 ). In the United Kingdom, the rates of smoking among both male and female individuals and the annual rates of lung cancer–related death ( Fig. 2.5 ) declined. These changes indicate that smoking cessation occurs as a result of public education about the risks of smoking in the years following these early epidemiologic studies on lung cancer.