An essential component to any surgical procedure is the documentation and labeling of the surgical specimen. Correct orientation of the specimen allows the pathologist to properly evaluate resection margins and correlate gross findings with the clinical history. It also allows for optimal oncologic outcomes, as the pathologist can notify the surgeon if additional tissue needs to be excised to achieve negative margins. In the case of breast-conservation therapy, it may also lead to improved cosmetic results with the removal of only the necessary tissue to achieve negative margins. The ultimate importance of labeling surgical resection specimens pertains to patient safety, as errors may lead to incorrect diagnosis and treatment.

In 1998, the American College of Radiology, the American College of Surgeons, the College of American Pathologists and the Society of Surgical Oncology published a report on consensus standards for diagnosis and management of invasive breast cancer. This report was a follow-up to their previously published report in 1992 establishing the initial consensus standards for breast-conservation treatment.1 The recommendations from the 1998 report stated that the surgeon must orient the specimen with the use of sutures, clips, multicolored indelible ink, or another suitable technique. It was noted that the specimen should not be sectioned before submission to the pathologist, and that any uncertainty regarding the proper orientation of the specimen should be clearly indicated to the pathologist by the surgeon. In terms of pathologic evaluation, the group stated that the specimen should be submitted with appropriate clinical history and specification of anatomic site, including laterality (left or right breast) and quadrant (upper-outer, lower-inner, etc). The surgeon should also orient the specimen (eg, superior, medial, lateral) with markers or sutures, as well as document the type of surgical specimen (lumpectomy, total mastectomy, etc).1,2

As a follow-up to the 1992 report, White et al3 disseminated a study-specific questionnaire to 842 hospitals, yielding a total of 16,643 patients throughout the United States to determine whether practice patterns for patients with breast carcinoma who underwent breast-conservation therapy were consistent with the standards established 2 years before Winchester et al.2 Poor compliance was noted with the labeling of lumpectomy specimens with the affected quadrant and proper spatial orientation. Furthermore, orientation of the specimen with suture or markers was noted for only 67% of cases.3

There remains a paucity of literature examining the outcomes of specimen identification errors. Makary et al4 chose to address this issue by prospectively examining errors that occurred in the “pre-analytical phase,” which they defined as the interval when the transfer of information from physician to nurse during a procedure takes place, with subsequent specimen labeling, packaging, and transport. In a total of 21,351 surgical specimens, 91 (4.3 of 1000) surgical specimen identification errors were identified. Procedures involving the breast were the most common type to involve an identification error (11 of 91). The authors noted, however, that the extent of patient harm was unknown. In addition, they noted the potential for significant costs to the institution and distrust from the community.4

Currently, there is a lack of standardization for labeling specimens across institutions. Efforts are underway to improve consistency in specimen labeling and marking. The new Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization National Patient Safety Goals requires the labeling of specimens with at least 2 patient identifiers and that the specimen containers are labeled in the presence of the patient, with a preoperative verification step occurring in the presence of a physician.5 Several groups have implemented using methods such as radio-opaque threads,6,7 radio-opaque clips, metal clips, and/or silk suture for marking specimens. When used correctly, silk suture remains the standard, cost-efficient manner for orienting specimens.

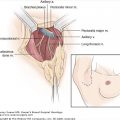

Segmental and total mastectomy specimens both require marking to orient the pathologist regarding how the specimen resided in situ. There are several dimensions to each specimen, including the following designated margins: superior (12 o’clock position), inferior (6 o’clock position), medial (3 o’clock position on the right breast, 9 o’clock position on the left breast), lateral (3 o’clock position on the left breast, 9 o’clock position on the right breast), anterior (toward the skin), and posterior (toward the chest wall). By convention, we traditionally only mark the superior and lateral margins.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree