Thyroidectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Complete extracapsular dissection of the thyroid

Identification and preservation of the parathyroid glands

Identification and preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerves

En bloc resection of locally advanced thyroid cancer

1. COMPLETE EXTRACAPSULAR DISSECTION OF THE THYROID

Recommendation: In cases of biopsy-proven papillary thyroid cancer, the thyroid lobe or entire thyroid gland should be removed by using the technique of extracapsular dissection.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, low-quality evidence.

Rationale

The optimal treatment for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) requires complete excision of the primary tumor. If total thyroidectomy is to be performed for a unilateral thyroid cancer, resection of the thyroid lobe that harbors the malignancy should be performed first.1,2 (Please see the Key Question at the end of this chapter for discussion of the extent of initial thyroid surgery.) Cytological proof of a PTC is sufficient and obviates the need for intraoperative pathologic evaluation. Although most thyroid cancers are intrathyroidal and do not demonstrate evidence of extrathyroidal extension, the recommended technique for thyroidectomy is to perform complete removal of the thyroid lobe by extracapsular dissection. Attempts at removal of individual nodules are fraught with potential pitfalls. These include difficulty controlling bleeding from the violated thyroid capsule and parenchyma, oncologic concerns regarding adequacy

of resection margins and the possible presence of multifocal disease, and creation of scar tissue in the resection bed that would make future operations in the ipsilateral neck more difficult. Extracapsular dissection of the thyroid gland requires knowledge of cervical anatomy and an understanding of the physiologic and functional consequences of manipulation and possible injury to cervical structures. The identification and preservation of the parathyroid glands and the recurrent laryngeal nerves are discussed in later sections of this chapter.

of resection margins and the possible presence of multifocal disease, and creation of scar tissue in the resection bed that would make future operations in the ipsilateral neck more difficult. Extracapsular dissection of the thyroid gland requires knowledge of cervical anatomy and an understanding of the physiologic and functional consequences of manipulation and possible injury to cervical structures. The identification and preservation of the parathyroid glands and the recurrent laryngeal nerves are discussed in later sections of this chapter.

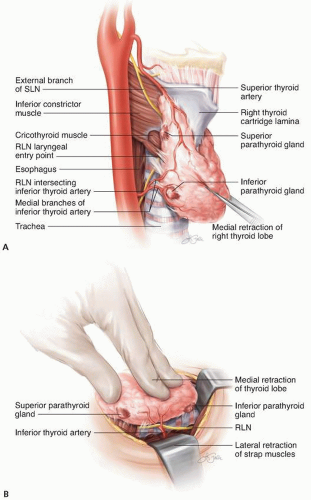

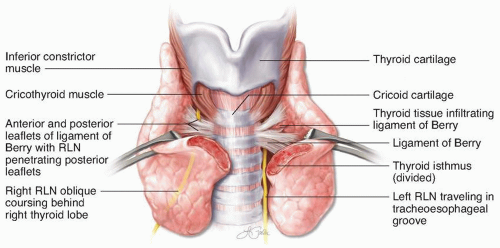

The technique for extracapsular dissection of the thyroid has been developed and refined over the past century. Despite the introduction of multiple technologic advancements (especially in tissue coagulation and hemostasis), the basic principles of this operation remain the same. The thyroid gland is approached through a cervical incision through skin, subcutaneous tissues, and the platysma muscle. The overlying strap muscles are elevated off the anterior surface of the thyroid lobe. Neither division nor resection of the strap muscles is typically required unless there is evidence of tumor involvement or the thyroid lobe is so large that strap muscle division will facilitate its removal. The thyroid isthmus may be divided to improve retraction of the lobe, but care must be taken to avoid disrupting tumor margins. Small (1- to 2-cm) isolated tumors located in the thyroid isthmus may be considered for isthmusectomy alone. The thyroid lobe should be dissected free of surrounding structures and its vascular pedicles divided. This typically requires coagulation or ligation of vessels in the areas of the superior and inferior poles, including the middle thyroid vein when present (Fig. 1-1). Dissection of the superior pole should be performed near the thyroid capsule and away from the cricothyroid muscle to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The tubercle of Zuckerkandl, a posterolateral projection of the lateral thyroid lobe toward the pharynx, should, when present, be dissected free of its attachments to the anterior surface of the trachea (ligament of Berry) and the inferior border of the cricothyroid muscle (Fig. 1-2).3 This approach typically requires meticulous dissection in the area of recurrent laryngeal nerve insertion into the larynx, which is deep to the lower border of the inferior constrictor muscle, just posterior to the cricothyroid articulation. Once removed, the specimen should be oriented. A common method of orienting the specimen for the pathologist is to place a suture to designate laterality.

2. IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE PARATHYROID GLANDS

Recommendation: The surgeon should attempt to identify and preserve parathyroid glands encountered during the course of thyroidectomy. Nonviable parathyroid glands should be autotransplanted after pathologic confirmation that the tissue is indeed parathyroid and does not represent thyroid cancer or lymph node metastasis.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

Every surgeon performing thyroidectomy should have a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the parathyroid glands. Their preservation may factor into the extent of the oncologic procedure. Transient hypocalcemia occurs in 5% to 40% of patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, whereas permanent hypoparathyroidism (defined as a requirement for calcium and vitamin D lasting >6 months after thyroidectomy) occurs in 0.5% to 4% of these patients.4,5,6,7,8,9

The parathyroid glands may have variable locations depending on their embryologic descent. The inferior parathyroid glands are typically located near the inferior pole of the thyroid lobe, anterior and medial to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Preservation of the inferior parathyroid gland requires dissection of the gland away from its attachments to the thyroid capsule, preserving the vascular pedicle. This can be accomplished by using a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. Rarely will the inferior parathyroid gland be located in an intrathyroidal position within the thyroid parenchyma such that it cannot be preserved during thyroid resection. The superior parathyroid glands are typically located in a position posterior and lateral to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. They are frequently encountered during dissection of the superior pole of the thyroid lobe and must be dissected free of the thyroid and preserved with blood supply intact. Please see the next chapter for discussion of parathyroid preservation during central compartment neck dissection.

Upon the completion of thyroid resection, the thyroid specimen should be examined closely for parathyroid glands or tissue. In addition, the in situ parathyroid glands should be visually inspected. Potential signs of devascularized parathyroid glands

may include duskiness or discoloration. Any devascularized or inadvertently removed parathyroid glands should be autotransplanted.10 A small sliver of the gland should be sent to the pathologist for intraoperative consultation to confirm parathyroid tissue. This will help prevent accidental reimplantation of thyroid cancer or nodal metastasis. Once the tissue is confirmed to be parathyroid, the remaining gland should be minced into submillimeter sections. The sternocleidomastoid muscle, either ipsilateral or contralateral, is easily accessible and is a suitable location for reimplantation; forearm reimplantation is typically reserved for surgeries involving parathyroid pathology, such as secondary hyperparathyroidism, and patients with multiple endocrine neoplasias. For reimplantation, a small pocket is made in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the minced parathyroid tissue is directly inserted or injected. The pocket is clipped or sutured closed and may be marked with a clip (if sutured) in case the autotransplanted gland needs to be located and resected in the future.

may include duskiness or discoloration. Any devascularized or inadvertently removed parathyroid glands should be autotransplanted.10 A small sliver of the gland should be sent to the pathologist for intraoperative consultation to confirm parathyroid tissue. This will help prevent accidental reimplantation of thyroid cancer or nodal metastasis. Once the tissue is confirmed to be parathyroid, the remaining gland should be minced into submillimeter sections. The sternocleidomastoid muscle, either ipsilateral or contralateral, is easily accessible and is a suitable location for reimplantation; forearm reimplantation is typically reserved for surgeries involving parathyroid pathology, such as secondary hyperparathyroidism, and patients with multiple endocrine neoplasias. For reimplantation, a small pocket is made in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the minced parathyroid tissue is directly inserted or injected. The pocket is clipped or sutured closed and may be marked with a clip (if sutured) in case the autotransplanted gland needs to be located and resected in the future.

After thyroid lobectomy alone, calcium and parathyroid hormone levels are not typically monitored because the undisturbed contralateral parathyroid glands should be sufficient to maintain calcium homeostasis. After total thyroidectomy, surgeons should have a protocol for evaluating postoperative hypocalcemia in the immediate postoperative period.11,12,13

3. IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF THE RECURRENT LARYNGEAL NERVES

Recommendation: The surgeon should attempt to identify and preserve recurrent laryngeal nerves during thyroidectomy.

Type of data: Retrospective case series.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve is a dreaded complication of thyroidectomy and represents the most common reason for malpractice claims against thyroid surgeons.11,12,14 Transient recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy occurs in 1.4% to 38% (mean, 9.8%)15 of thyroid operations, whereas the reported rate of permanent vocal cord paralysis is 0% to 18% (mean, 2.3%).15 This wide range of reported injury rates is likely due to variability in the experience of surgeons performing thyroid operations, as well as differences in practice patterns regarding routine preoperative and postoperative laryngoscopy for documentation of vocal cord mobility.16,17 The thyroid surgeon should have a comprehensive understanding of the normal and variant anatomy of the recurrent laryngeal nerves in order to minimize the risk of complications. Knowledge of bilateral nerve function may affect oncologic decision-making.

The recurrent laryngeal nerves are derived from the vagus nerves (cranial nerve X), which descend from the jugular foramen in the carotid sheath. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve originates from the vagus nerve at the level of the aortic arch, just distal to the ligamentum arteriosum (obliterated ductus arteriosus), and travels cephalad

in the tracheoesophageal groove before entering the larynx at the level of the cricoid cartilage and cricothyroid muscle. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve branches off the vagus nerve at the level of the right subclavian artery and travels cephalad in a more oblique trajectory toward its insertion in the larynx. A nonrecurrent right laryngeal nerve is seen in <1% of patients and is associated with an aberrant right subclavian artery originating directly from the aortic arch and traveling behind the esophagus (artery lusoria).

in the tracheoesophageal groove before entering the larynx at the level of the cricoid cartilage and cricothyroid muscle. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve branches off the vagus nerve at the level of the right subclavian artery and travels cephalad in a more oblique trajectory toward its insertion in the larynx. A nonrecurrent right laryngeal nerve is seen in <1% of patients and is associated with an aberrant right subclavian artery originating directly from the aortic arch and traveling behind the esophagus (artery lusoria).

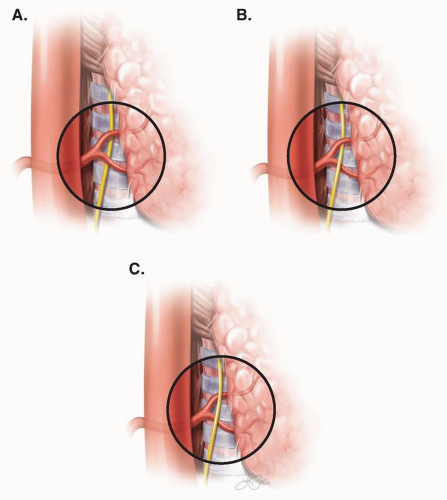

The recurrent laryngeal nerve can be most reliably identified at three anatomic locations during thyroidectomy. Some surgeons elect to dissect the nerve proximally, near the point where the nerve emerges from the mediastinum, and follow the course of the nerve as it traverses the central neck toward the larynx. This approach may be limited by fibrofatty tissue and central neck lymph nodes obscuring the course of the nerve. The recurrent laryngeal nerve can also be identified in the area of the tubercle of Zuckerkandl, where it is typically associated with the inferior thyroid artery (Fig. 1-3). Occasionally, the nerve may be located behind thyroid tissue in the tubercle, necessitating close dissection and risking bleeding from thyroid parenchyma. The nerve also may be identified at its insertion point into the larynx at the level of the cricoid cartilage. This often requires fine dissection of the tubercle and the ligament of Berry, and identification at this distal entry point does not prevent injury to the nerve more proximally during the mobilization of the remainder of the thyroid lobe.

Intraoperative nerve monitoring is an increasingly utilized technologic adjunct that may assist in identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroidectomy.18 Some surgeons routinely use nerve monitoring in all cervical operations, whereas others reserve it for reoperative cases, large goiters, or other more challenging situations. There are no level 1 data to support the use of nerve monitoring to reduce the risk of injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves, but many surgeons believe that nerve monitoring is useful for confirming their visual identification of the nerve and helping them predict which patients may or may not have voice issues after thyroidectomy.18 Possible signs of nerve injury may include true loss of the electromyography signal during resection of the first lobe (e.g., troubleshooting fails to identify a modifiable cause of the loss of signal), loss of the laryngeal twitch reflex, or clear visual evidence of nerve damage.19 During planned total thyroidectomy, it may be prudent to terminate the operation before proceeding to the contralateral thyroid lobe if there is concern that the recurrent laryngeal nerve has been injured.

4. EN BLOC RESECTION OF LOCALLY ADVANCED THYROID CANCER

Recommendation: Advanced thyroid cancer should be resected en bloc with surrounding tissues when feasible.

Type of Data: Retrospective case series.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, low-quality evidence.

FIGURE 1-3 Depiction of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, with variations in its course, with respect to the inferior thyroid artery. A: Recurrent laryngeal nerve coursing posterior to the inferior thyroid artery. B: Recurrent laryngeal nerve coursing between branches of the inferior thyroid artery. C: Recurrent laryngeal nerve coursing anterior to the inferior thyroid artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|