Clinical manifestation

Chyloperitoneum or chylous peritonitis

Chyledema of the lower limbs

Chyledema of the external genitalia

Chyluria

Chylothorax

Chylorrhea

Chylous arthritis

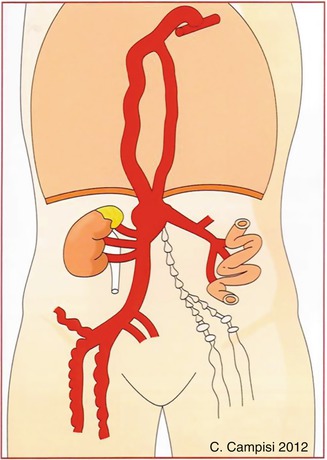

Remarks on the Thoracic Duct Anatomy

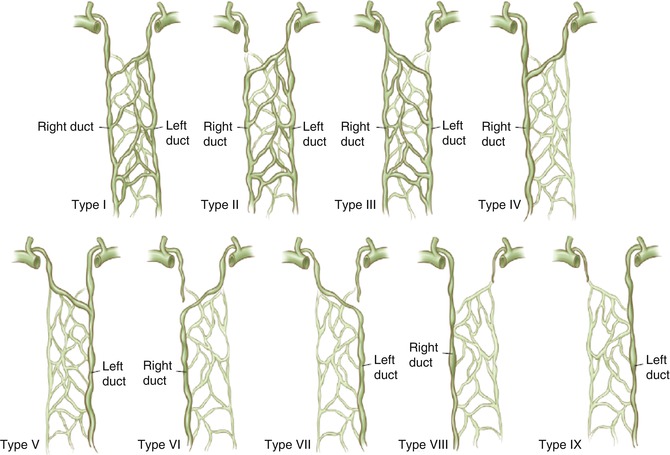

In the embryo, the thoracic duct originates from six lymphatic sacs, two of which arise from the internal jugular and subclavian veins. The right and left lumbar lymphatic channels stem from several branches and eventually converge to form the thoracic duct [1]. Multiple variations in the thoracic duct anatomy exist in the general population, as is evident in Fig. 52.1. Kato et al. [2] examined the anatomical course of the thoracic duct in 8 patients noting 1 with a right-sided thoracic duct that flowed into the right venous angle, 4 patients had divergences, 1 patient showed an “island” thoracic duct that splits partially into two channels, and 2 patients had variants that flowed through the left subclavian artery into the left venous angle. The outlet of the thoracic duct empties into the great veins of the neck on the left side in approximately 95 % of cases, into the right side of the neck in 2–3 % of cases, and bilaterally in 1.0–1.5 % of cases [3]. The marked variation from the “normal” thoracic duct described in anatomical textbooks evident in a significant amount of the general population may also be due to basing anatomical studies on cadavers, whereas the thoracic duct in living subjects is swollen with lymph, and this may displace it slightly [4].

Fig. 52.1

Variations in the development of the thoracic duct. The most common types are type VI at 63 % and type II at 27 % (Reproduced with permission from [1])

Thoracic Duct Malformations and Related Chylous Reflux Syndromes

Aside from anatomical variations within the general population, the thoracic duct can also be congenitally malformed. Malformations may include ectasia, agenesis, dysplasia, and/or cysts. Thoracic duct cysts generally develop in the cisterna chyli, the mediastinum, or occasionally in the neck. Congenital weakness, incompetence, or absence of valves lead to obstruction at the lymphatic-venous junction, thus allowing reflux of blood into the thoracic duct. Such cysts usually present with left-sided supraclavicular swelling. Preyer et al. [5] reported that noninflammatory supraclavicular tumors were likely due to chronic localized lymph stasis provoking lymphangiectasia. This lymph stasis was probably due to an anatomical variation that allowed the intermittent occlusion of the duct by the internal jugular vein. They also postulated the role of female hormones in exacerbating the growth of the tumor. Other thoracic duct malformations such as lymphangiomatosis or diffuse lymphangiectasia or thoracic duct atresia, aplasia, hypoplasia, or dysplasia may all cause chylous disorders, such as chylothorax. These may allow the effusion of chyle into the pleural cavity. But there may also be variations within the thoracic duct that do not cause overt chylous symptoms. For example, Hara et al. [6] demonstrated the presence of thoracic duct abnormalities in patients with only primary lymphedema of the extremities.

A malformation of the thoracic duct, cisterna chyli, Pecquet cyst, and/or chyliferous vessels creates a significant obstacle to the lymphatic flow, sometimes presenting as a downstream leakage, uni- or bilateral chylothorax, lymphocele, chylous cyst, mediastinal chyloma, chylomediastinum, and chylopericardium [7–9]. The loss of the chyle leads to nutritional deficiencies, dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, and lymphocyte leaks. This leads to increased risk of infection and eventually respiratory dysfunction [10]. If the obstruction in lymphatic flow persists, there may be an eventual effect on intestinal drainage. The chyliferous vessels of the small intestine become dilated from chyle stasis. This can lead to chylous ascites, chylorrhea in the genitalia, and chylous edema of the lower limbs. Patients may also present with protein-losing enteropathy symptoms due to the failure to absorb proteins by the intestinal lymphatic system. Dual diagnoses are often present; in a sample of patients with primary chylous disorders, 30 % had both chylothorax and chylous ascites, and 70 % of these also had chylous reflux into the lower limbs [11]. In addition, thoracic duct malformations [12] and the possible coexistence of normal variations within the thoracic duct anatomy [1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 13] present an unknown risk for surgery, particularly that involving the head and neck, that is difficult to plan for. The resulting complex clinical picture can be challenging to manage and often requires a multidisciplinary approach with a coordinated treatment plan.

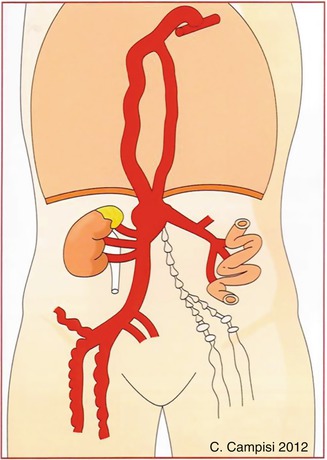

Clinical Diagnosis

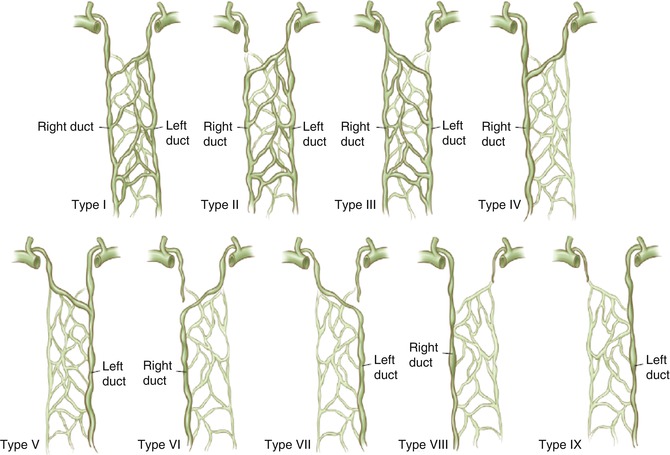

The existence of a malformation of the chyliferous vessels and of the Pecquet cyst considerably obstructs the intestinal lymphatic drainage. The lymphatic collectors along the walls of the small intestine and mesentery dilate, filling with chyle. Considering their position just subperitoneal, they are prone to breakage, resulting in the leakage of chyle into the peritoneal cavity (chylous ascites). Sometimes the breaking of the chyliferous vessels occurs in two stages; chyle escapes from the broken lymph collectors in the peritoneum, which then results in the formation of a chyloma that subsequently opens around the abdominal cavity. The finding of localized dilation of a chyliferous vessel is defined as a chylous mesenteric cyst (Fig. 52.2).

Fig. 52.2

Schematic design concerning the pathophysiological and relevant clinical characteristics of disorders of the chyliferous vessels, cistern chili, and thoracic duct

Given the complex clinical presentation of these cases, a thorough diagnostic assessment is recommended [8, 14, 15]:

Blood tests: serum protein, albumin, triglyceride, cholesterol, calcium, and hemoglobin levels; lymphocytes and immunoglobulins can leak into the ascites fluid. Lymph in the thoracic duct contains from ~2,000 to 20,000 lymphocytes per mm3, that is, a concentration of lymphocytes two to ten times higher than in the blood.

Thoracocentesis or paracentesis: chyle is evident by its distinctive milky color but also by chemical analysis demonstrating raised triglyceride levels (generally greater than 110 mg/dl is considered diagnostic) and the presence of lipoproteins and chylomicrons. Thoracocentesis or paracentesis may, in themselves, provide symptomatic relief.

Thoracoabdominal CT scan and MRI can exclude malignancies. A recent study has demonstrated that unenhanced MRI can visualize the thoracic duct and tributaries to identify leakage sites [16].

Lymphoscintigraphy can be useful to demonstrate lymphatic dysplasia involving all compartments of the body, including the peritoneal, external genitalia, and lower limbs. Lymphoscintigraphy allows excellent confirmation of the patency of lymphatic-venous anastomoses post-surgery. Lymphoscintigraphy with 99mTc-filtrated sulfur colloid has recently been reported to visualize the thoracic region and lymphatic leakage into pleural cavities [17].

Lymphangiography: after isolation and cannulation of the lymphatics, standard lymphangiography is conducted by means of microsurgically injected liposoluble ultrafluid contrast medium. If coupled with a CT scan, lymphangiography allows a more accurate assessment of the extent of disease, as well as the site of the obstacle and source of chylous leak.

In order to demonstrate concurrent protein-losing enteropathy, albumin-labeled (99 m Tc) scintigraphy can be used to show the enteropathy inside the intestinal lumen in scans taken 1–24 h after intravenous administration of 740 mBq.

Videothoracoscopy or videolaparoscopy: as an initial approach, videothoracoscopy and videolaparoscopy are preferred for correct placement of drains. Smaller drains placed by an ultrasound or CT-guided approach tend to occlude as chyle is viscous. Sclerosing agents, such as povidone-iodine, and antibiotics may be introduced via these drains. Lavage with a Trémolliéres sterile solution (concentrated lactic acid) combined with an antibiotic (250–500 mg of sodium rifampicin) associated with a rigorous total parenteral feeding has proved to be successful in chyloperitoneum in 2 or 3 weeks maximum.

Therapeutic Procedures

Regarding the therapeutic approach, these complex clinical cases, also in the case of an acute onset (e.g., chylous peritonitis), should not be treated too early by surgery, at least not until the patients have been adequately metabolically stabilized with an appropriate diet. This diet is based on the reintegration of protein and lipid uptake, by limiting only to medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) that, instead of being absorbed by the intestinal chylo-lymphatics, are cleared through the portal venous system. Notably, in order to achieve the most rapid state of metabolic control, an initial regimen of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) can be initiated in order to significantly reduce the source of the chylous leak.

Nonsurgical Procedures

Conservative management of chylous leaks remains the first choice of intervention. There remains some controversy about the timing of surgical intervention, as discussed below, but the general consensus is that the patient should be stabilized first and a proper diagnostic evaluation conducted to identify the source of the chylous leak. Conservative measures include nutritional management, administration of somatostatin analogs, and drainage of the leak.

Nutritional options consist of a low or fat-free diet, enteral nutrition including the use of medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) solutions, or total parenteral nutrition without oral intake. Necessarily, patients should be individually evaluated to determine the most effective type of regimen. As noted by Campisi et al. [18] in their review of chyle leaks in head and neck surgery, all patients must be closely monitored for clinical response irrespective of the nutritional approach employed. This includes nutritional status and protein levels, essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins, and the electrolyte balance to avoid nutritional deficiency or further complications.

Somatostatin is a peptide that acts as a neurohormone as well as a paracrine agent, acting on both the endocrine and paracrine pathways. Octreotide is a synthetic octapeptide that mimics the action of somatostatin, and both have significant action on the gastrointestinal tract. Although the mechanism(s) of action of these peptides remains unclear, it is likely that they cause a reduction of the gastrointestinal blood flow and therefore indirectly reduce lymphatic flow from these areas. Octreotide is also reported to work directly on the somatostatin receptors, minimizing lymphatic secretion [19]. Initially used in pediatric cases of chylous disorders, there are emerging cases of somatostatin and octreotide being used successfully in the suppression of chylous leaks in adults. The efficacy of these peptides in the treatments of high-output chyle flow (more than 1 l per day) is yet to be established [20].

Surgical Procedures

Retrospective accounts indicate that approximately 60 % of patients with chylous disorders will undergo surgical intervention. There is no clear treatment algorithm to guide surgical planning, and general consensus remains that surgery is required in refractory chyle leaks that fail to respond to conservative measures. Definitions of “refractory” chyle leaks are based in the literature on the output of chyle leaks (above 500 or 1,000 ml per day recommending surgical treatment) or a specific time interval (2 weeks of conservative treatment prior to surgery resulted in lower overall morbidity than only 48 h of treatment) [21].

Thoracic Duct Ligation

Thoracic duct ligation is often undertaken to disrupt the flow of chyle. Given the extensive network of lymphatic anastomoses and lymphaticovenous anastamoses between the thoracic duct and the azygos and the intercostal and lumbar veins, it is assumed that occluding the thoracic duct will allow safe rerouting of the chyle flow [22]. Thoracic duct ligation can be performed through an open thoracotomy, but, more recently, a thoracoscopic approach has been successfully used for the treatment of chyle fistulas. Usually, the thoracic duct is identified via a right-sided approach, but of course, natural anatomical variations must be taken into account. Occlusion of the duct occurs by mass ligation of the tissue above the supradiaphragmatic hiatus between the azygos vein and the aorta. This procedure is effective, avoiding the significant morbidity of major thoracic access [23–30]. Intrapleural fibrin or biological glue has also been used to occlude the duct [31, 32].

Some concern has been raised that significant occlusion of the thoracic duct may lead to the redistribution of the chylous flow, such as leg swelling and chylous ascites [18, 33–35]. The development of protein-losing enteropathy, chronic diarrhea, and lower limb swelling has also been demonstrated in experimental studies after thoracic duct ligation [36]. Of note, one case study implicated a thoracic duct ligation performed for idiopathic chylopericardium in the development of chyloptysis 7 years later. The authors suggested that the high-pressure lymphatic flow through the rerouted channels gradually dilated the lymphatic valves, eventuating in retrograde flow of chyle into the peribronchial pulmonary lymphatics. Prospective follow-up studies are needed to confirm the associated risks of thoracic duct ligation [18].

Surgical/Microsurgical Approaches

Surgical decisions should be based on the severity of the case, number of chylous leaks, whether there is a primary or secondary cause for the chylous effusion, and the success of previously implemented nonsurgical methods in slowing or stopping the leak. Depending on the specific clinical picture, the following types of surgical/microsurgical procedures can be performed:

Identification of the sites(s) of chylo-lymphorrhea, chyloperitoneum, and chylothorax drainage.

Thoracoscopic pleurodesis and decortication.

Ruptured lymphatic vessels can be ligated, oversewn, or clipped as necessary.

Removal of lymphocele, chylous cysts, and/or chylomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree