“Absolute” contraindications:

Ongoing bleeding or recent severe bleeding

Known bleeding diseases

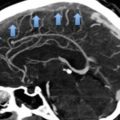

Intracranial bleeding or previous intracranial bleeding

Structural intracranial cerebrovascular diseases that increase risk for bleeding (e.g., aneurysm)

Some malignant intracranial tumor (depends on type of tumor) [15]

Aortic dissection

Recent intracranial or spinal surgery

Severe closed-head or facial trauma within 3 months

Recent (<3 months) ischemic stroke

Recent head or facial trauma with brain injury or bone fracture

Recent major surgery (within 1 week) [15]

Relative contraindications or cautions:

Recent major surgery or trauma (within 2–3 weeks) [15]

Internal bleeding within 2–4 weeks

Severe uncontrolled hypertension (i.e., systolic >200 mmHg or diastolic >110 mmHg)

Ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack during past 3–6 months [15]

Severe liver diseases

Active gastrointestinal ulcers during past 3 months

Acute pancreatitis

Bacterial endocarditis or pericarditis

Traumatic or prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation (>10 min)

Pregnancy

Peripartum period [15]

Age >75 years

Dementia

Diabetic retinopathy

4 Benefits of Thrombolytic Therapy and the Risks of Bleeding Complications

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled studies involving 2057 patients reveals that systemic thrombolysis is associated with reduction of overall mortality only when high-risk PE is included in the studies (OR, 0.59; 95 % CI, 0.36–0.96) [16]. Thrombolytic treatment is also associated with reduction in the combined endpoint of death or treatment escalation (OR, 0.34; 95 % CI, 0.22–0.53), mortality related to PE (OR, 0.29; 95 % CI, 0.14–0.60), and recurrence of PE (OR, 0.50; 95 % CI, 0.27–0.94). On the risk side, systemic thrombolysis is associated with fatal or intracranial hemorrhage (OR, 3.18; 95 % CI, 1.25–8.11), and major bleeding (OR, 2.91; 95 % CI, 1.95–4.36) [16].

5 Thrombolytic Drugs

For most practical purposes it will be sufficient for most readers of this review to have a thorough knowledge of alteplase. These drugs activate plasminogen by different mechanisms to form plasmin, a natural proteolytic enzyme that breaks the crosslinks between the fibrin molecules in a thrombus. Plasmin can also cleave fibrinogen, factor V, and factor VIII, giving rise to generalized coagulopathy. There are two groups of fibrinolytic drugs: fibrin-specific agents, e.g., tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and non-fibrin-specific agents, e.g., streptokinase and urokinae.

tPA is naturally present in the vascular endothelial cells. It shows considerable affinity and specificity for fibrin. Alteplase is recombinant human tPA (rt-PA) and is identical to human tPA. rtPA binds selectively to fibrin on the surface of the thrombus and thereby activates fibrin-bound plasminogen. This event favors local fibrinolysis at the site of the thrombus, leading to a lower incidence of major bleeding [17]. The half life of alteplase is about 5 min, and it is therefore usually used as a continuous infusion. In contrast to streptokinase, it is not antigenic. Alteplase is the lytic agent most commonly used for thrombolysis in PE.

Retaplase is a second-generation recombinant human tPA that contains 355 of the 527 amino acids of native tPA. It is more potent and rapid acting than alteplase. The half-life of reteplase is about 15 min, and it is usually given as intravenous bolus injection. Desmoteplase has higher fibrin specificity and a longer half-life (4 h). Reteplase and desmoteplase have similar effect as rtPA in PE [18, 19], but these drugs are still not widely used or recommended for the treatment of PE.

Tenecteplase is a third-generation rtPA, a 527-amino-acid glycoprotein with several modifications in the amino acid molecules. The result of these modifications is that it binds with fibrin with a higher affinity than alteplase and is associated with fewer bleeding complications. It has a longer half-life and, therefore, can be administered as a bolus injection. It has been used in the treatment of PE [5].

Stretopkinase is less expensive and is still used in many developing countries. In the developed countries it is used less and less because of its high antigenicity and many adverse effects, and because it causes systemic fibrinolysis rather than fibrin-specific fibrinolysis.

6 Administration of Thrombolytic Drugs

In this section, I mainly discuss the use of alteplase. In emergency situations, thrombolytic treatment should be started without delay. In addition to the treatment by thrombolytic agents, patients in severe hypotension or shock will need parallel resuscitation and stabilization. In this context, it should be noted that many aspects of fluid therapy and treatment by vasoactive drugs in PE remain controversial. One should order baseline blood tests for prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), full blood count, fibrinogen, serum creatinine, and liver function tests before starting thrombolytic therapy.

If the patient has already received LMWH or fondaparinux, warfarin, or one of the NOACs, and you decide to treat by thrombolytic agents, you can still start treatment by alteplase immediately. You can do this irrespective of the dose or time of the last dose of heparin, LMHW, fondaparinux, warfarin, or the novel oral anticoagulants. If the patient is receiving unfractionated heparin infusion, this can be continued during the infusion of altiplase (if you are going to use streptokinase or urokinase, then stop the heparin infusion during the infusion of streptokinase or urokinase). Adjust the rate of heparin infusion to keep the APTT between within 1.5 and 2.5 times the normal reference values.

For patients who weigh less than 65 kg, the total dose must not exceed 1.5 mg/kg. Regimens for treatment by alteplase vary depending on the urgency of the situation, bleeding risks, guidelines from major societies or regulatory authorities, and even local traditions. There are insufficient data to compare the effectiveness of specific types of regimes. There is some evidence that alteplase infusion is more effective than bolus dose alteplase in the treatment of PE in most situations [20].

We usually give 10 mg altiplase i.v. as a bolus injection in 2 min, and then 90 mg as an infusion over 2 h.

An alternative regime is to give alteplase 50 mg as an infusion during 30 min, and then another 50 mg during 90 min.

In critical conditions, give alteplase 0.6 mg/kg (maximum, 50 mg) as an i.v. bolus injection over 5–15 min, and then 50 mg as an infusion over 90 min.

The British Thoracic Society recommends giving 50 mg alteplase as a bolus injection to patients with imminent cardiac arrest suspected to be caused by PE [10].

If the risk of bleeding is considered high, then give 50 mg as an infusion over 1–1.5 h, and then, if there is no improvement, give 0.6 mg/kg (maximum, 50 mg) as an infusion over another 1 h.

According to one study, infusion of 50 mg alteplase in 2 h has a similar effect as infusion of 100 mg alteplase in 2 h [23]. In this study, there was less bleeding tendency in the 50 mg regimen compared to the 100 mg regimen, especially in patients with body weight <65 kg (14.8 % vs. 41.2 %).

7 Care of the Patients During and After Thrombolysis

When possible, the patient should be transferred promptly to a unit that has experience and resources for administering such treatment and for appropriate monitoring. We usually transfer our patients to an intermediate care or intensive care unit. Patients should be under strict bed rest. Blood pressure and pulse should be monitored continuously for up to 24 h after administration of alteplase. Patients should be monitored frequently for signs and symptoms of bleeding and for neurological symptoms. Neurological status should be checked every 15 min during infusion of alteplase, then every 30 min for 6 h, and then hourly for 24 h.

Do not give intramuscular or subcutaneous injections during and 4 h after thrombolysis. After intravenous injections or blood sampling, use a compression bandage for at least 10 min to reduce bleeding from the puncture site. Refrain from eventual insertion of a urinary catheter and venous or arterial punctures during the first 24 h after administering alteplase.

8 Treatment After Thrombolysis

If you stopped heparin infusion during infusion of alteplase, then restart heparin infusion, without a bolus dose, after the end of the alteplase infusion. Check APTT and adjust the rate of heparin infusion (or stop heparin infusion temporarily) to maintain the APTT within 1.5 to 2.5 times the upper limit of normal. If the patient received LMWH or fondaparinux once or twice daily, before the start of alteplase, then start heparin infusion 24 h or 12 h, respectively, after the last injection.

Heparin infusion should be continued for at least 4 h, or often longer, after the end of the alteplase infusion. We usually continue heparin infusion for 1 day and then switch to LMWH, or fondaparinux, if the patient is hemodynamically stable, and if there is no clinically significant bleeding. If the latest APTT is less than 140 s, you can stop the heparin infusion, and switch to LMWH, or fondaparinux at full dose, immediately after stopping the heparin infusion. If the latest APTT is more than 140 s, then start LMWH, or fondaparinux, 2 h after stopping the heparin infusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree