Introduction

The salivary glands are composed of paired parotid, submandibular, lingual and several hundred minor salivary glands that are distributed throughout the upper aerodigestive system. Diseases of the salivary glands are heterogeneous and may present to a number of specialist clinicians. The usual presentation of a ‘lump’ may indicate localised pathology affecting part of the gland, or may be part of a diffuse involvement of the entire gland.

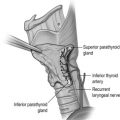

Surgical anatomy

The parotid gland

The parotid gland is the largest of the salivary glands and produces mainly serous saliva. It covers the area anterior to the tragus of the external ear from the zygomatic arch superiorly to the upper neck inferiorly. It overlies the masseter muscle anteriorly and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle inferiorly. It is shaped like a wedge, lying between the ramus of the mandible anteriorly and the mastoid bone and temporal bone posteriorly. Its medial/deep lobe occupies the pre-styloid component of the parapharyngeal space and approaches the lateral wall of the oropharynx. The parotid (Stensen) duct passes across the masseter, piercing the buccinator and opens into the oral cavity opposite the second upper molar tooth. Pre-auricular lymph nodes, draining the temporal region of the scalp and face, lie on the surface of the parotid, within its capsule (condensation of fascia) and also in the substance of the gland itself.

Facial nerve

The facial nerve is motor to the muscles of facial expression, stapedius, stylohyoid and the posterior belly of digastric, sensory to a small patch of the external ear canal, and carries special sensory (taste) fibres to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Its long pathway within the skull runs from the internal acoustic meatus, through the middle ear cavity and mastoid bone, before exiting the skull base via the stylomastoid foramen. It then enters the substance of the parotid gland, forming into its two main divisions and major branches, and thus dividing the parotid gland into what are known clinically as superficial and deep lobes. The identification of the main facial nerve trunk, two main divisions and branches is the cornerstone of nerve-sparing parotid surgery. The five main branches of the nerve are the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical. Often, anastomoses will occur between branches, forming a plexus. The mandibular division of the nerve often overlies the submandibular gland and the implications of this will be discussed in the surgical principles section below.

The submandibular gland

The submandibular gland produces partly mucinous and partly serous saliva, and accounts for most saliva produced at rest. The gland lies between the mandible superolaterally, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle antero-inferiorly and the posterior belly of digastric postero-inferiorly. Superficially the gland is covered by the deep layer of the investing cervical fascia. On this lie the mandibular and cervical branches of the facial nerve, and superficial to the nerves and fascia lies the platysma muscle. The importance of this is discussed further in the surgical principles section. The gland is divided into the so-called superficial and deep lobes as it hooks around the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle. The deep lobe lies on the hyoglossus muscle medially, with the lingual nerve positioned superiorly and the hypoglossal nerve inferiorly. The duct (Wharton) runs anteriorly with the deep lobe to open into the oral cavity lateral to the frenulum of the tongue.

The sublingual gland

Whilst certainly a discrete gland, some consider the sublingual glands to be an amalgamation of minor salivary glands, because they do not have capsules, do not have a ductal system and open directly onto the mucosa or into the submandibular ductal system. They produce mucinous saliva. The gland lies deep to the mucosa of the floor of the mouth between the mylohyoid and genioglossus muscles. It lies in close proximity to Wharton’s duct, into which some of its saliva drains.

Investigations

Clinical assessment

For most patients, the history is the most useful single guide to the diagnosis. The presenting symptom is most often of a mass in the salivary gland (see Box 8.1 ).

- •

Does the pathology affect part or all of the gland?

- •

Is one or more than one major salivary gland affected?

- •

How long has it been present?

- •

Is pain a feature?

- •

Is there fluctuation in size with eating?

- •

Is there a past medical history of chronic inflammatory disorders?

The duct orifices should be inspected intraorally, preferably prior to palpation, which should be performed bimanually with a gloved finger in the mouth. Note if there is xerostomia or any stigmata of connective tissue disease. Examine the oropharynx for any deep lobe extensions. Measure the mass and note its exact position within the gland identified. Grade facial nerve function, e.g by the House–Brackmann scale, as a baseline and to monitor for future change. Examine the cervical lymph nodes and finally the external auditory meatus, to ensure no direct spread of a parotid neoplasm.

Imaging

The choice of which imaging modality depends on the clinical indication and the local availability and expertise in imaging techniques and their interpretation. The options include plain radiographs, sialography, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and nuclear scintigraphy; each has a place.

Plain radiographs retain a role predominantly in the diagnosis of submandibular duct calculi, 90% of which are radio-opaque.

Sialography is considered the most appropriate and sensitive in assessing ductal pathology but is increasingly being replaced by magnetic resonance (MR) sialography and ultrasound. A sialagogue is first used to stimulate saliva production to identify the duct. This is cannulated and contrast injected under fluoroscopic control to ensure adequate filling. Plain X-rays are taken to identify filling defects, delays in emptying and extravasation. Digital subtraction sialography removes the pre-contrast image from the post-contrast image to give improved identification of filling defects within the duct system. The disadvantages of sialography are that it is invasive, it can fail if the duct cannot be cannulated and it cannot be performed in the setting of acute salivary gland infection.

Ultrasound (US) is increasingly the imaging modality of choice for the initial investigation of salivary glands. It is cheap, widely available and avoids the use of ionising radiation. It is excellent at imaging superficial structures such as the parotid and submandibular glands. An advantage of US is that it can allow simultaneous and guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). US will pick up 90% of salivary gland stones and can characterise salivary gland tumours in great detail, but the technique is highly operator dependent. US will not identify the facial nerve or bone erosion, and the mandible impedes visualisation of the deep parotid lobe.

Recent studies suggest that for clinically benign superficial lobe parotid tumours, there is no benefit in additional imaging after good-quality US examination and that the move towards surgical management of benign tumours with extracapsular dissection means that the identification of the facial nerve is less of an intraoperative issue. Brennan et al. studied 37 such patients and found that US imaging was sufficient as a single modality before surgery in 34 patients. In the three patients that had ultrasound features suggestive of malignancy (benign cytology and subsequent benign tissue pathology), the preoperative review of CT and MRI imaging did not change the surgical management plan. This study suggests that US is adequate to guide surgical management for superficial tumours with benign features.

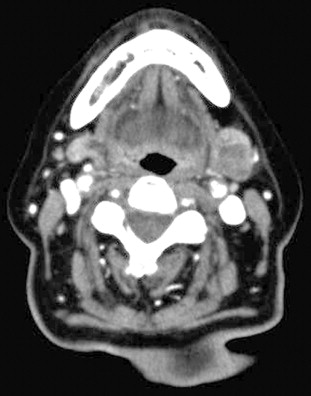

Computed tomography (CT) is generally more accessible and cheaper than MRI but images can be distorted by dental artefacts ( Fig. 8.1 ). It is superior to MRI in evaluation of bony cortical involvement in malignant disease. Non-contrast images will identify sialolithiasis within sialadenitis in the benign setting. CT is also useful in imaging the thorax and, where necessary, the abdomen in the case of metastatic disease from and to the salivary glands. However, its disadvantage is the relatively high dose of ionising radiation involved. Cone-beam CT has, however, similar radiation to sialography and is an emerging variant. MRI gives better defined soft-tissue images than CT as well as better imaging of the facial nerve and tumours in the deep lobe, clearer definition of anatomical relations to cranial nerves and perineural spread, and is thus superior in planning a surgical approach to the tumour. Low signal intensity on T2-weighted images and post-contrast ill-defined margins of a parotid tumour are highly suggestive of malignancy. Where identification of the nerve is particularly important, the use of new MRI techniques, such as gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state (GRASS) and balance turbo field echo (BTFE) sequences, may improve definition.

For suspected malignant tumours a combination of both MRI and CT is often performed to allow precise tumour localisation and identification of bone invasion, perineural spread or distant metastases.

Nuclear scintigraphy is now increasingly available. The most commonly utilised scan in the head and neck region is positive emission tomography combined with CT (PET-CT). The injection of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) identifies tissues with high metabolic activity, notably malignant tumours. Image quality is poor in terms of fine anatomical definition and the scan is designed to broadly identify sites of malignancy, particularly metastases and sites of unknown primary tumours.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) can be used as a first-line investigation of a major salivary gland lesion. FNAC is performed with either a 23- or 25-gauge needle attached to a 20-mL syringe. The needle should be inserted into the target lesion, applying suction if possible, with gentle rotation about its long axis while making several passes of forwards and backwards movement through the lesion. If blood is aspirated, repeat aspiration is advisable. The syringe is detached and air withdrawn into it prior to reattaching it to the needle so that material is then expressed from the needle onto a slide. It is then spread over the slides without pressure to avoid crushing the material, taking care not to heap the aspirate up at the edges of the slide. The slides can then be air-dried or fixed with alcohol spray, ideally one or more of each.

The ideal management of patients with salivary masses is in the context of a one-stop clinic where the clinician is able to perform outpatient-based ultrasound-guided FNAC, with a cytology technician present in the clinic to confirm the presence of cellular material within the sample. An inadequate aspirate can be repeated at the same clinic appointment, and on-site microscopy can reduce the non-diagnostic rate to less than 1%.

Salivary gland FNAC aims to distinguish neoplastic from non-neoplastic disease and, more importantly, also benign from malignant neoplasms. Clearly, knowing that a salivary gland lesion is malignant aids surgical planning. A systematic review of the accuracy of FNAC quotes positive predictive values from 16 studies, including 1782 cases of FNAC with histological concordance. In the case of a ‘benign’ FNAC result, the final histological diagnosis was confirmed as benign in 95% of cases. In malignancy the concordance was 93%. A recent systematic review of ultrasound-guided core biopsy found it to be more accurate than FNAC in determining benign from malignant pathology (sensitivity 92%, specificity 100% in the five studies included), compared with reports of equivalent 72% sensitivity and 100% specificity from ultrasound-guided FNAC.

The take-home message is therefore that a positive result from either cytology technique is strongly suggestive of a malignancy, but FNAC yields more false-negative results for malignancy than core biopsy. The improved sensitivity of core biopsy is to be expected as far more tissue is obtained, but the investigation is more painful for patients and has a higher risk of haematoma formation. In the case of non-diagnostic initial cytology, repeat FNAC of salivary gland neoplasms has been shown to improve sensitivity from 70% to 84%. However, this still does not reach the sensitivity of core biopsy. If there is clinical or radiological suspicion of malignancy and in a situation where the cytology could alter the surgical treatment plan for an individual patient, then a core biopsy should be recommended following a negative initial FNAC.

Sialendoscopy

Sialendoscopy is the use of low-diameter optical endoscopes in the diagnosis and treatment of Stenson’s and Wharton’s pathology. It is most applicable to patients who have symptoms of salivary gland swelling on eating, indicative of a stone or stenosis. Diagnostic sialendoscopy may distinguish between stones, stenosis, mucous plugs or debris within the duct, all of which may present in a similar manner. It has also been used in the treatment of childhood sialolithiasis, juvenile recurrent parotitis and autoimmune disease, to dilate Stenson’s duct in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Interventional sialendoscopes incorporate a working channel, through which Dormia baskets, guide wires, laser fibres and balloons can be passed (see below).

Non-neoplastic disease of the salivary glands

Inflammatory conditions

Acute viral inflammation

The commonest cause of acute viral parotitis is mumps, caused by the paromyxovirus. The combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was introduced throughout the UK in 1988 as a single dose, with a double-dose vaccine replacing this in 1996. The incidence of mumps was reduced by vaccination, but there has been a UK epidemic over the past decade, with a peak of 43 000 cases of mumps in 2005. Whereas mumps most commonly occurs in 4- to 6-year-olds, this rise was due to increasing numbers of adolescents getting the disease, too old to have received the vaccine prior to its routine introduction, or having only received the single-dose vaccine and then attending university, the ideal semi-closed environment to allow the virus to spread. The diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed by serology, demonstrating antibodies to mumps S and V antigens. It can also be diagnosed by saliva testing for immunoglobulins. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to further assay any negative samples. Malaise, fever and loss of appetite, followed by acute bilateral parotid enlargement, are typical presentations. The parotitis may be unilateral. About 30% of cases present as swelling in the submandibular and sublingual glands. Systemic complications include meningitis, encephalitis, hepatitis, carditis, orchitis and hearing loss. Treatment is symptomatic. Other viruses may mimic mumps: coxsackie A, enteric cytopathic human orphan (ECHO) virus, influenza A and cytomegalovirus.

Acute suppurative sialadenitis

Bacterial salivary gland infections are relatively uncommon and most frequently occur in the parotid gland. Traditionally, postoperative patients were deemed most at risk. With improved perioperative care and hydration this is now less common. However, the presentation of unilateral parotid enlargement with cellulitis in the dehydrated elderly patient still occurs. Pus may be expressed from the duct orifice and should be swabbed for microbiology. The commonest causative agent is Staphylococcus aureus . Haemophilus influenza is also common, but up to half of microbial isolates may be anaerobic, usually Gram-negative bacilli ( Prevotella , Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium spp.). Intravenous antibiotic treatment should cover both aerobic and anaerobic organisms, and rehydration is important. Occasionally, abscess formation can accompany the presentation. If suspected, an ultrasound scan will confirm the presence of pus and therefore the need for incision and drainage. Acute bacterial salivary gland infections may also occur with duct calculi.

Chronic inflammatory conditions

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) of the salivary glands is relatively rare in the UK. It may present as would a malignant tumour, with enlargement and pain, most commonly in the parotid gland. It is due to infection within the periparotid lymph nodes, rather than the gland parenchyma. A positive Mantoux test is suggestive. A chest radiograph may confirm coexistent pulmonary TB. Although definitive diagnosis was traditionally through an incisional biopsy sent for both histology and microbiology, aspiration of frank pus may allow identification of acid fast bacilli on microscopy and culture, thus avoiding the risk of leaving a discharging sinus. Typical caseating granulomata may be seen. Antituberculous chemotherapy is usually delivered by a respiratory or infectious disease physician.

Atypical tuberculosis

This is now an increasingly common condition affecting children, usually between the ages of 2 and 5, being rare after the age of 12. Although there are 13 ‘atypical’ strains of Mycobacterium , Mycobacterium avium intracellulare is the commonest, probably transmitted through contact with soil. The patient has painless lesions over either the parotid or submandibular glands, but is otherwise well. The infection is actually within the periglandular lymph nodes and any of the cervical lymph nodes can be affected. As the lymph nodes enlarge, pus may form and progression affects the skin, causing a typical discoloration before breakdown occurs. Whilst combination antibiotics are favoured by many (clarithromycin, ethambutol and rifampicin), some paediatric surgeons feel the diagnosis is so obvious clinically that surgical excision of all involved nodes is preferable, before the skin changes occur. There is also doubt as to the advantage, if any, conferred by antituberculous therapy. Where the salivary glands are involved, surgery requires gland excision. Wide local excision is advocated over an initial incisional biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. If an incisional biopsy is performed there is a risk of causing a chronic sinus and subsequent definitive surgery is less likely to control the disease. Left untreated the natural history of the disease is to break through the skin, discharging as a sinus on a chronic basis, before ‘burning out’. The end result is scarring of the overlying skin.

Cat-scratch disease

This is a granulomatous disease affecting the periglandular lymph nodes in the parotid and submandibular regions. The disease is caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Bartonella henselae and transmitted through a bite or scratch from a domestic cat. The cat flea is the vector for spread between animals and possibly also to humans. Serological testing of IgG and IgM, by immunofluorescence antibody testing, at presentation, and a rising titre at 10–14 days will confirm the diagnosis. It presents as a discoloured mass progressing to cervical lymphadenopathy, with 25% suffering with low-grade pyrexia. Swelling of the parotid gland may also occur. It may also manifest as Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome or granulomatous conjunctivitis in association with ipsilateral pre-auricular lymphadenopathy. Treatment is supportive, although occasionally surgery may be considered for persistent, enlarging, tender lymphadenopathy. Antibiotics have no proven role in disease resolution. A single randomised trial showed an improvement in lymphadenopathy, as measured by ultrasonography, at 30 days with a 5-day course of azithromycin, but no benefit over placebo at 2 and 4 months.

Actinomycosis

The Gram-positive anaerobe, Actinomyces israelii , causes painless hard masses in the neck that may overlie the salivary glands. The infection may involve the mandible, especially in the presence of osteoradionecrosis. Necrosis and multiple sinus tracts often occur within the lesions. Treatment consists of surgical debridement or excision with long courses of antibiotics.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterised by non-caseating granulomata. It is thought to be mediated by Th1 lymphocytes, and interleukin (IL)-17A has been implicated in granuloma formation. The disease most commonly affects young adults. Any organ can be involved but the lungs are the most commonly affected and extrapulmonary disease is usually associated with lung disease. The salivary glands, usually the parotids, are involved in 10–30% of patients, with non-tender, diffuse swelling of the glands. Intraoral nodules may also occur. Rarely, Heerfordt-Waldenstrom’s syndrome occurs, with uveitis, parotitis, fever and facial nerve palsy. Imaging of the parotid glands may show multiple non-cavitating masses. FNAC is useful in excluding malignancy. The diagnosis may be suggested via a chest radiograph, demonstrating mediastinal lymphadenopethy with or without pulmonary infiltrates, in association with a raised serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level. Serum levels of IL-18 are also elevated. Ultimately, a tissue diagnosis of non-caseating granulomata is required. This can be performed by biopsy of the salivary glands, intraoral sublabial biopsy, or a mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy. Treatment most frequently consists of systemic steroids or steroid-sparing immunosuppressants.

Sjögren’s syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is the most common autoimmune disease to affect the salivary glands. It may be primary or secondary to another connective tissue disorder. The American–European Consensus lists six diagnostic criteria:

- 1.

Dry eye symptoms.

- 2.

Dry mouth symptoms.

- 3.

Objective eye signs (Schirmer test < 5 mm in 5 minutes, Rose Bengal score).

- 4.

Histopathology of minor salivary glands showing focal lymphocytic sialadenitis. The most accessible and reliable area to biopsy is the sublabial minor salivary gland tissue in the lower lip.

- 5.

Salivary gland involvement demonstrated on objective testing: reduced whole salivary flow, diffuse sialectasis, reduced scintigraphy uptake.

- 6.

Autoantibodies: anti-Ro or anti-La, or both.

The disease is most common in women aged 40–60 years, typically with dry, gritty eyes and a dry mouth. Reduced salivary function also affects swallowing and voice function, as well as leaving the patient susceptible to dental caries. Patients may be referred to an otolaryngologist with symptoms of recurrent salivary gland swelling, usually the parotids. Other systemic features of primary SS include arthritis, skin vasculitis and pulmonary fibrosis. Treatment involves saliva and tear replacement substitutes. Pilocarpine is used to improve any residual salivary gland tissue. Systemic therapy is delivered by a rheumatologist and may consist of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories for arthritis and immunomodulatory medications or steroids for more severe SS symptoms. Patients with SS are up to 16 times more likely to develop mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Any persistent swelling in the gland of a patient with SS should raise the possibility of lymphoma, prompting the standard work-up for a salivary gland neoplasm with imaging and FNAC. FNAC, being less accurate in diagnosing lymphoma, is chiefly used here to exclude other neoplasms.

Human immunodeficiency virus

Generalised parotid gland enlargement and xerostomia may be a presenting feature of undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The pathogenesis remains unclear, as the symptoms may not be related to direct infection of the salivary glands. Associated cervical lymphadenopathy may also feature. Lymphoepithelial cysts may occur, most commonly in the parotid and bilateral in nature. Conservative management of HIV-associated cysts is advocated.

Sialolithiasis

Calculus formation within the parotid and submandibular ducts is a common reason for surgical intervention. The submandibular gland is more commonly affected (60–70%). Wharton’s duct has a longer route than the parotid duct, the saliva produced by the submandibular glands is more mucinous in nature and the flow is against gravity, predisposing to stone formation. Conversely, salivary flow from the parotid gland is aided by the muscular squeeze of the masseter muscle, the saliva is more serous in nature and some of the drainage is in the direction of gravity.

Unlike renal calculi, metabolic disorders do not seem to predispose patients to salivary stones. Calculi tend to be composed of calcium carbonates and calcium phosphates along with glycoproteins and mucopolysaccharides. Theories for stone formation include the occurrence of intracellular microcalculi, which form a nidus when excreted into the duct, or mucous plugs of saliva may act as the nidus. Stones may either be single or multiple. Huoh and Eisele retrospectively looked at the aetiological factors in 153 patients with stone disease in California over nearly 10 years. In 82% the stone disease was submandibular. The patient population had a higher use of diuretics and there was a positive smoking history in 44% of patients.

The presentation of salivary duct calculi is that of a swollen gland on eating – ‘meal-time syndrome’. This may subside after hours, only to return. The other scenario is that of recurrent acute infections of the gland, each one causing further scarring to the duct and gland. The end result may be a chronically stenotic duct and fibrosed gland. Stone disease is not the sole cause for these symptoms, which can be due to duct stenosis or chronic sialadenitis.

Treatment

Acute intermittent episodes can be managed with conservative measures: warm compress, massage, sialogogues (for example, sherbet lemon sweets stimulate saliva production) and antibiotics in the event of infection. Small calculi may pass spontaneously. Chronic symptoms should be investigated with ultrasound, sialography or diagnostic sialendoscopy to determine stone location and ductal patency.

For submandibular duct stones, the stone can be excised intraorally from the duct. This is most appropriate for stones in the distal duct. The complications are those of recurrent stones and scarring of the duct, leading to further obstructive symptoms. Where local expertise allows, sialendoscopy is particularly useful in treating calculi. However, it is contraindicated in acute infective episodes. The remaining option, applicable for stones at the hilum of the submandibular gland or where the submandibular gland has become chronically fibrosed and symptomatic, is to excise the gland.

Treatment decision-making is more straightforward for submandibular gland stones. In the case of parotid calculi, conservative management and, where available, non-invasive techniques such as sialendoscopy and lithotripsy should be employed. Some experts now utilise a combined approach of sialendoscopy and minimally invasive open surgical procedures to remove large parotid stones. The aim is to avoid parotidectomy in this disease. For chronic sialadenitis, caused by stones or strictures, parotidectomy involves removal of all parotid tissue in the affected gland. Due to the inflammatory disease process, surgical dissection is challenging. An alternative conservative technique for sialadenitis of the parotid due to calculi or stricture is to ligate the parotid duct.

A further option for particularly large salivary gland stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. First introduced in 1986, this uses pressure to fragment stones, making them easier to be flushed out of the gland in saliva. The technique is minimally invasive and painless with few side-effects. Long-term follow-up studies show good results for selected patients and it can now be used electively before sialendoscopic techniques are undertaken. Results are better with smaller calculi and with parotid than submandibular disease.

Interventional sialendoscopy

The ability to remove salivary duct calculi with this method is dependent on the size and position of the stone. Calculi affecting the parotid or submandibular duct can be managed by interventional sialendoscopy (IS) alone when less than 3 and 4 mm, respectively. When larger than these sizes, combined treatment with IS, transoral excision, laser fragmentation, lithotripsy or external surgical approach may be considered. IS undoubtedly offers a genuine conservative approach to the management of salivary gland duct calculi and stenosis but the treatment tends to be concentrated in specialist centres. However, Bowen et al. have reported their preliminary experience in a newly developed sialendoscopy service. They report 36 procedures: 17 for calculi, 16 for recurrent sialadenitis and three for Sjögren’s syndrome. Symptoms fully resolved in 26. Thirteen stones were successfully removed, five purely by endoscopy with a mean size of 3.7 mm and eight by a combined endoscopic and external approach, with a mean size of 10.6 mm. One patient had a salivary fistula as a complication.

As mentioned, another use of sialendoscopy is to aid conservative surgical excision of larger salivary calculi, usually in the parotid. The standard treatment of such stones in previous times would have been a parotidectomy. Karavidas et al. describe 70 patients treated with a combined endoscopic and conservative external excision of parotid duct calculi. The stone is identified within the parotid duct by sialendoscopy and ultrasound. Either a pre-auricular incision or an incision directly over the stone is made to remove it. No facial nerve weakness or salivary fistulae were noted in this series.

Non-inflammatory conditions

Sialadenosis/sialosis

Sialadenosis or sialosis is a non-inflammatory, non-neoplastic, non-painful, bilateral swelling of the major salivary glands and is usually most clinically apparent in the parotid glands. Histologically it is characterised by acinar cell hypertrophy and atrophy of striated ducts associated with oedema of interstitial connective tissue. There are a number of factors associated with this condition, including some drugs (particularly antihypertensive medications, sympathomimetics, antithyroid agents and phenothiazines), endocrine disorders and nutritional disorders. Treatment of the underlying pathology is the mainstay of treatment. Surgical management should only be considered for failure of medical management coupled with gross cosmetic concerns.

Salivary gland cysts

Cysts chiefly affect the parotid glands and may be congenital or acquired. Acquired cysts must be distinguished from cystic neoplasms and as such many are surgically excised. Retention cysts occur after duct obstruction and can occur with sialadenitis or sialadenosis. Similar cysts can occur in Sjögren’s syndrome and HIV. Mucoceles are mucosal swellings containing mucus. Most are located in the lower lip from a minor salivary gland. A particular type of extravasation mucocele is the ranula ; these arise from the sublingual gland and are termed ‘plunging’ if they penetrate through the mylohyoid muscle into the neck.

Post-radiotherapy xerostomia

Radiotherapy to the head and neck region results in a chronic long-term dry mouth and is universally recognised by patients as one of the major determinants on quality of life after such treatment. Radiotherapy to the salivary glands results in decreased salivary flow. There is emerging evidence from randomised controlled studies supporting the use of intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in head and neck oncology, in allowing a reduced dose of radiation to the parotid glands resulting in an improved salivary flow. Whilst amifostine and pilocarpine have both been used to improve salivary flow, their use has never replaced the humble bottle of water in relieving the troublesome symptoms of a chronic dry mouth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree