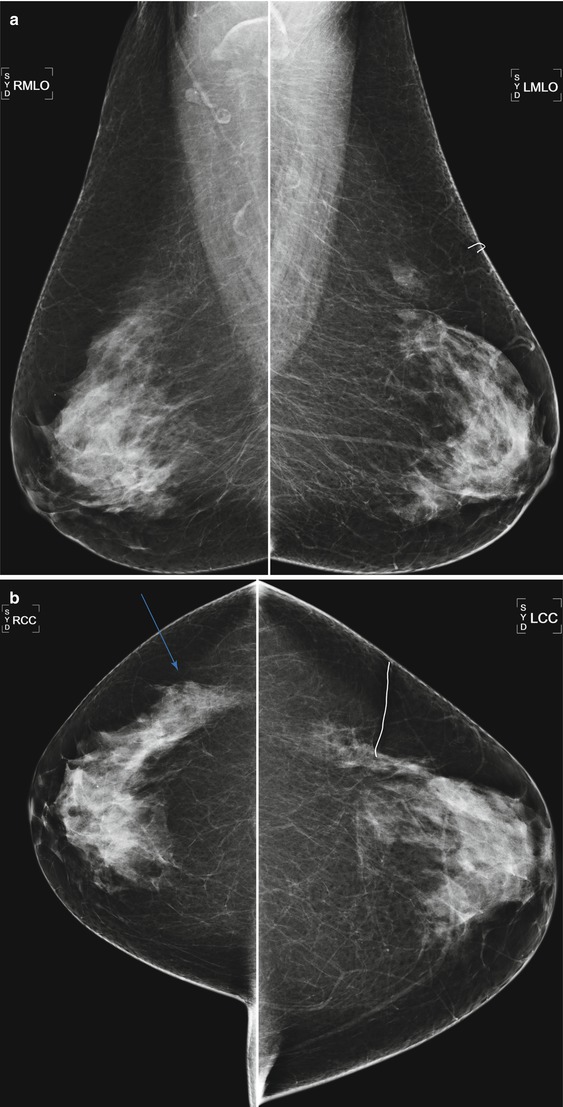

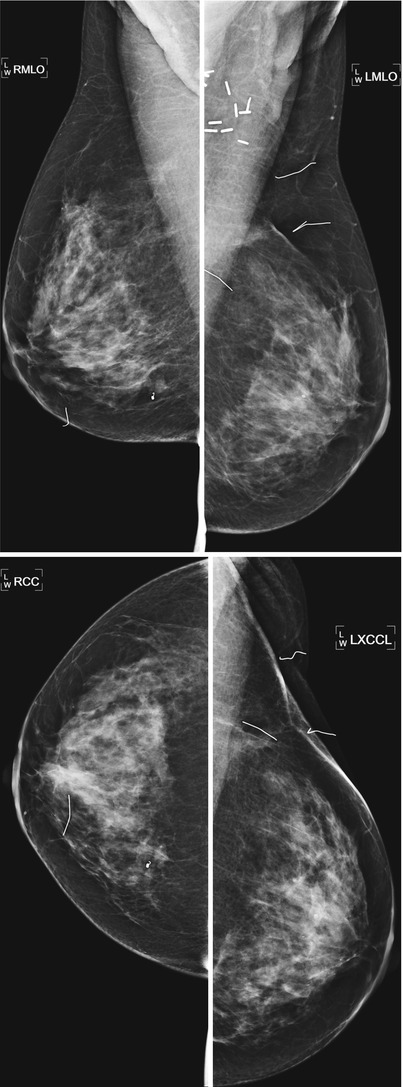

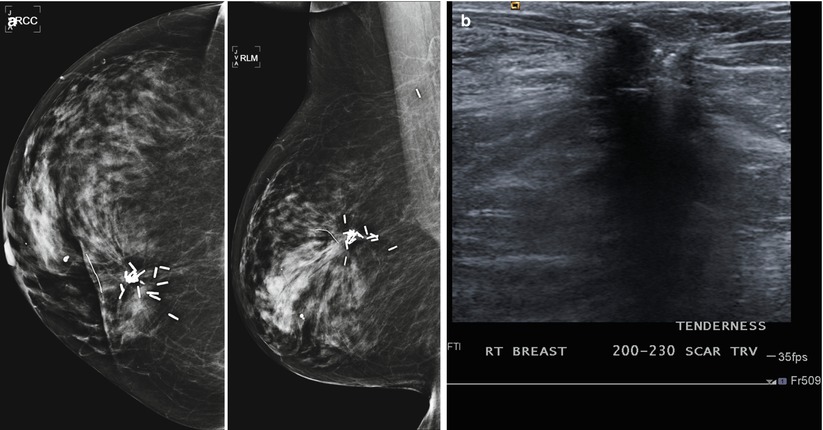

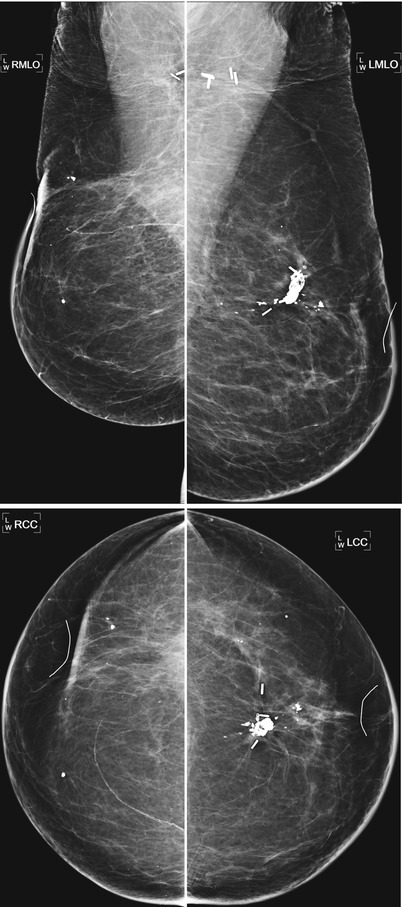

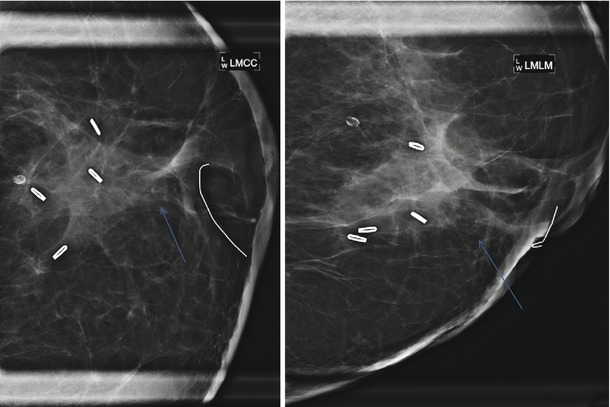

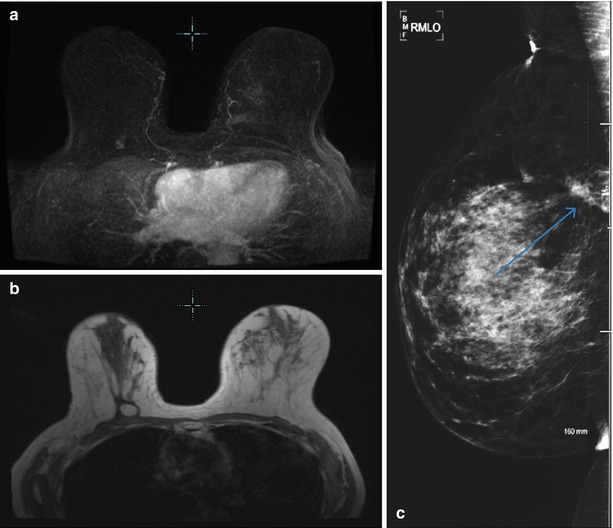

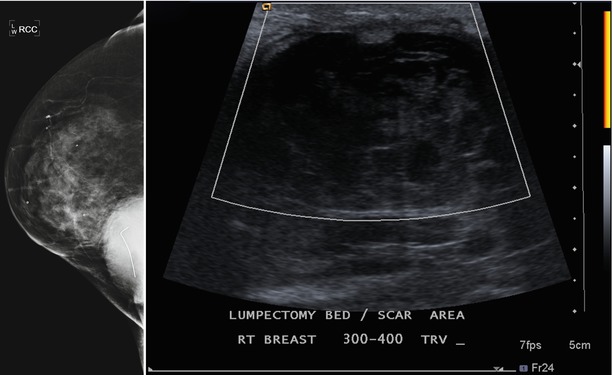

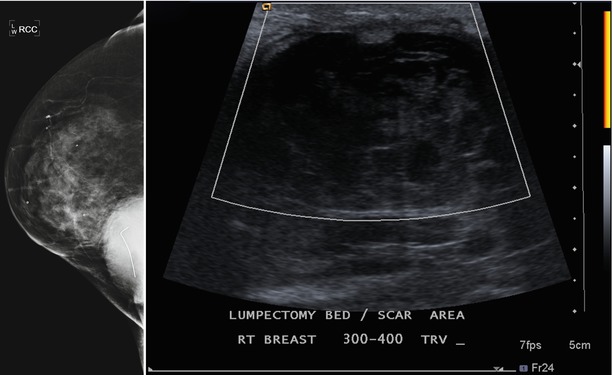

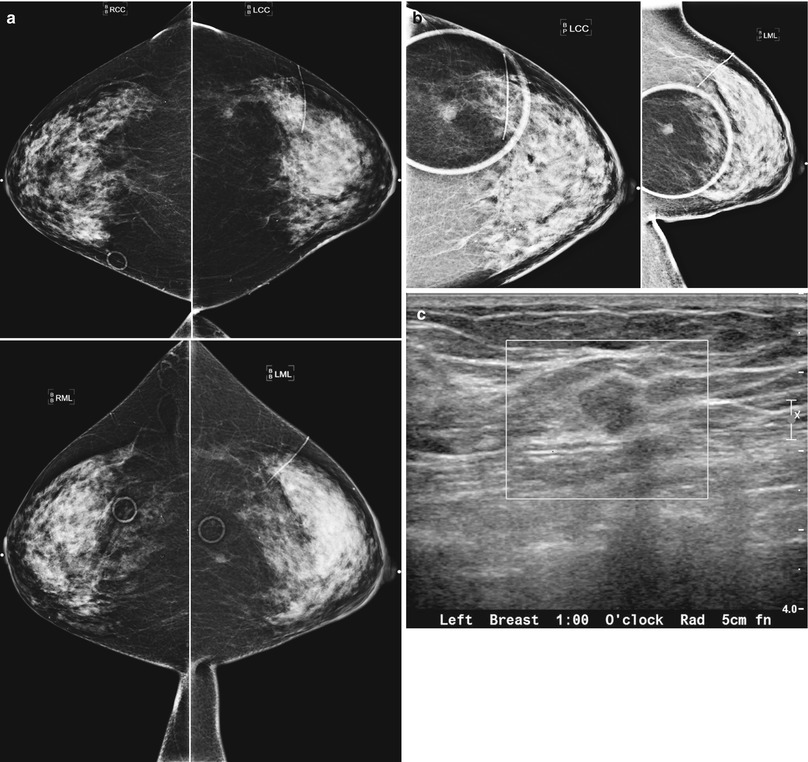

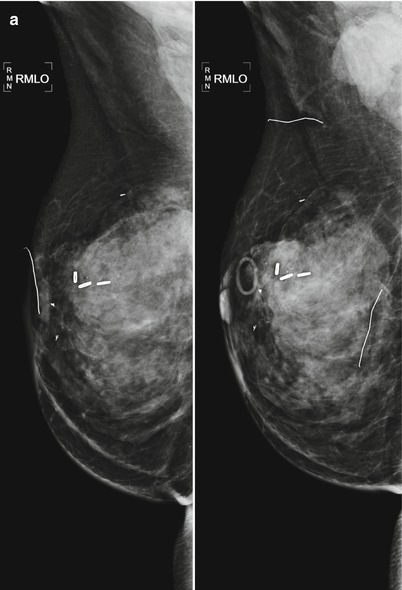

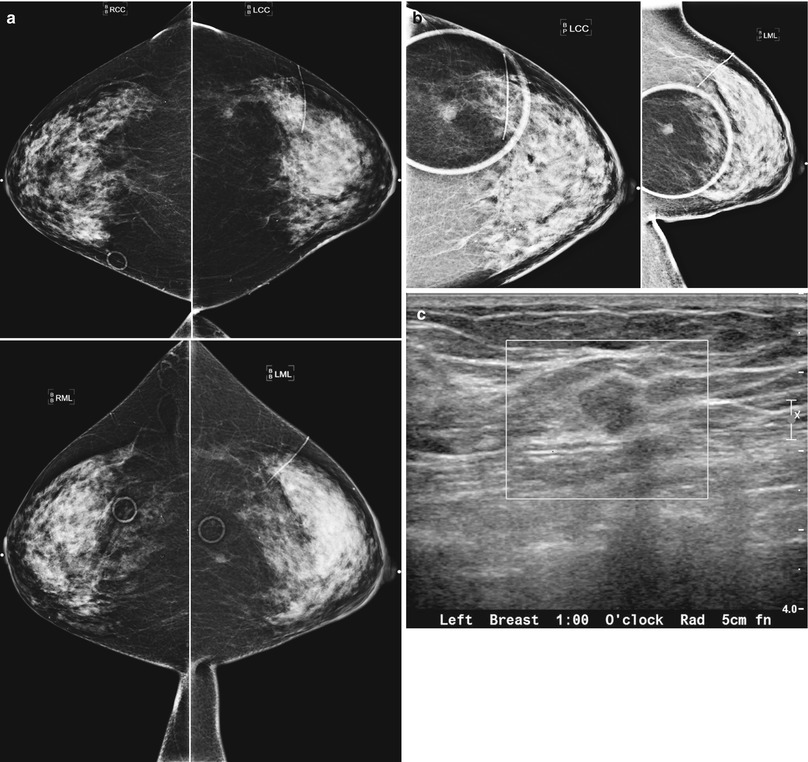

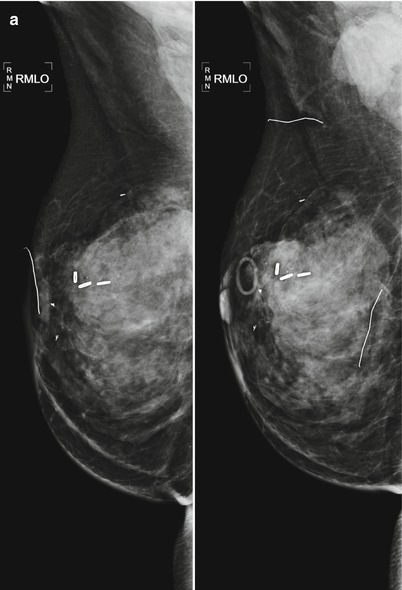

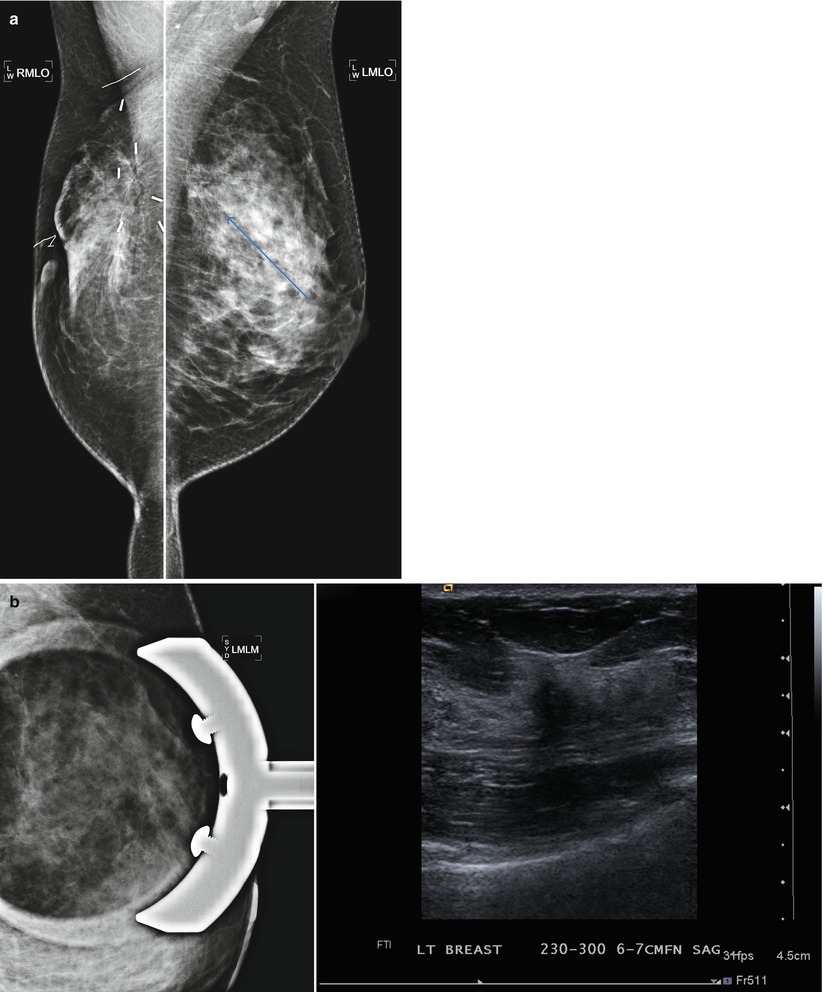

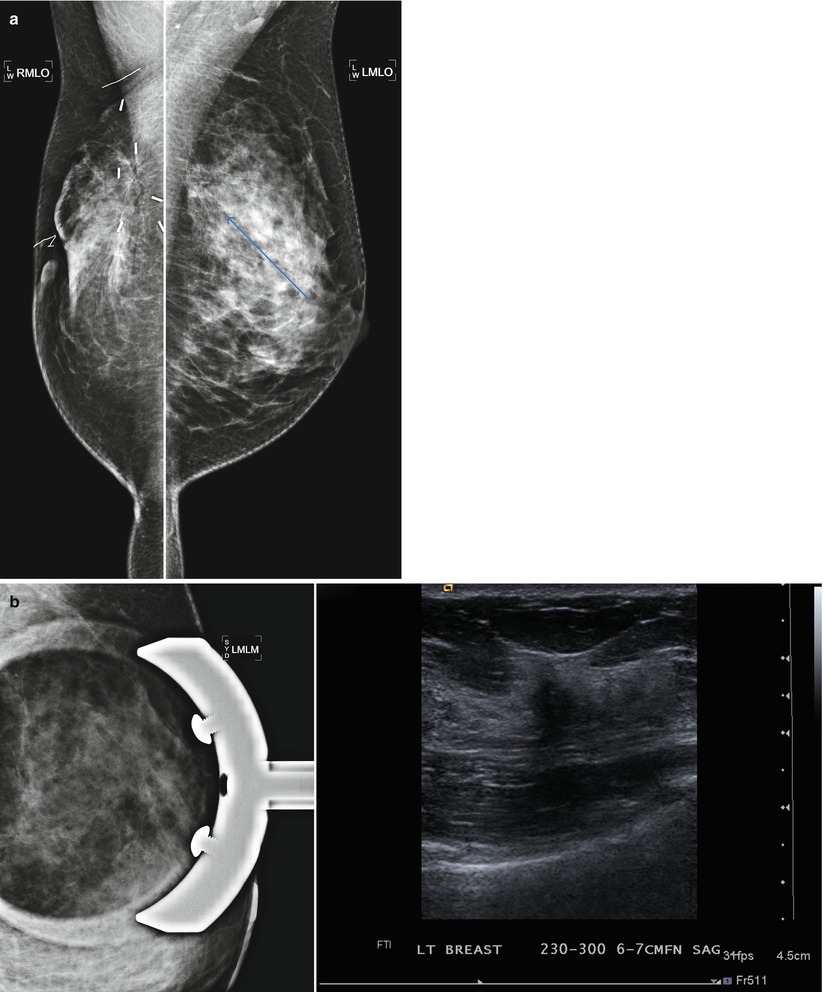

Fig. 16.1

Status post-excisional biopsy for ADH. Minimal postsurgical changes are present in the anterior upper central right breast

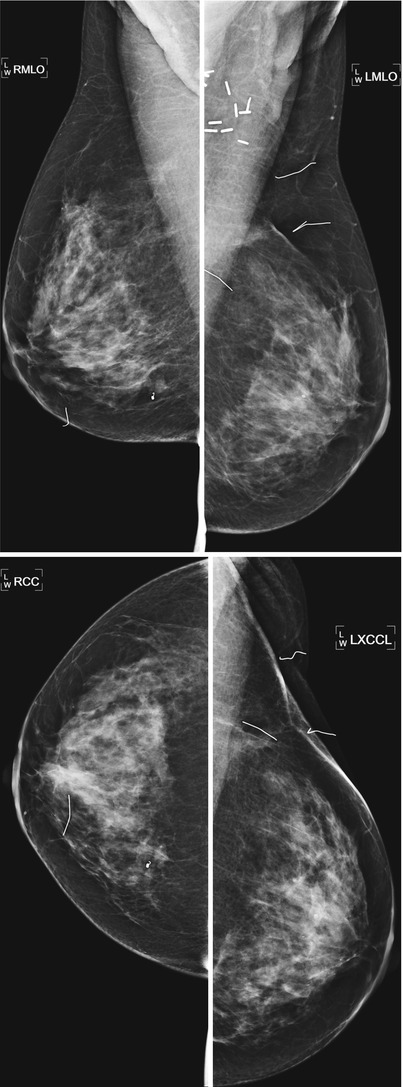

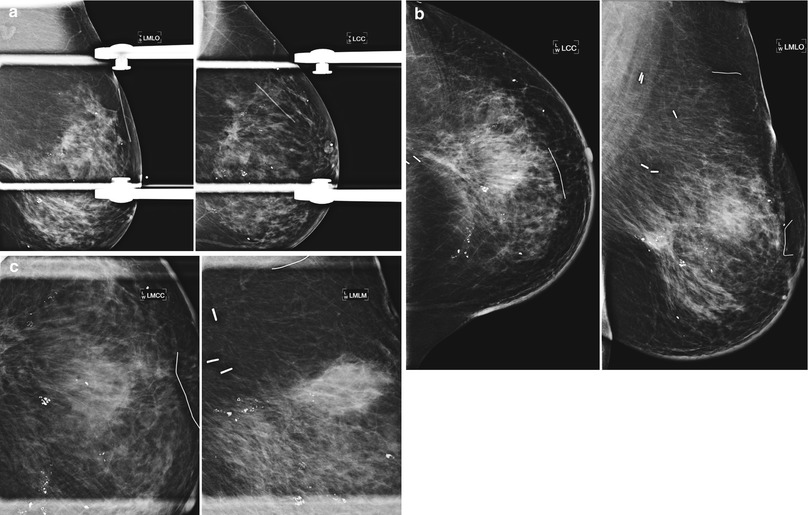

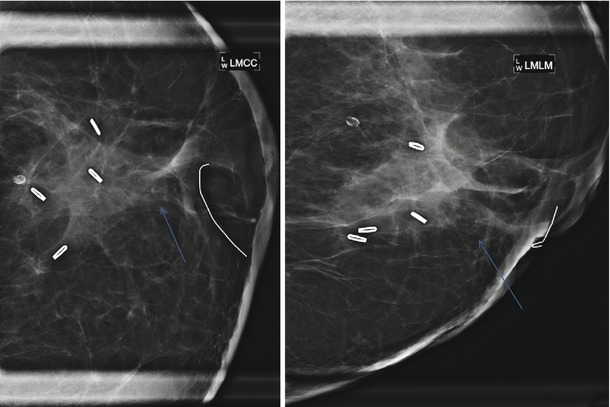

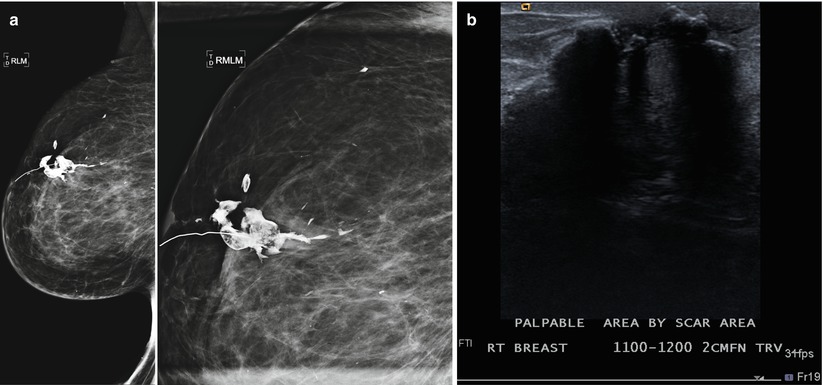

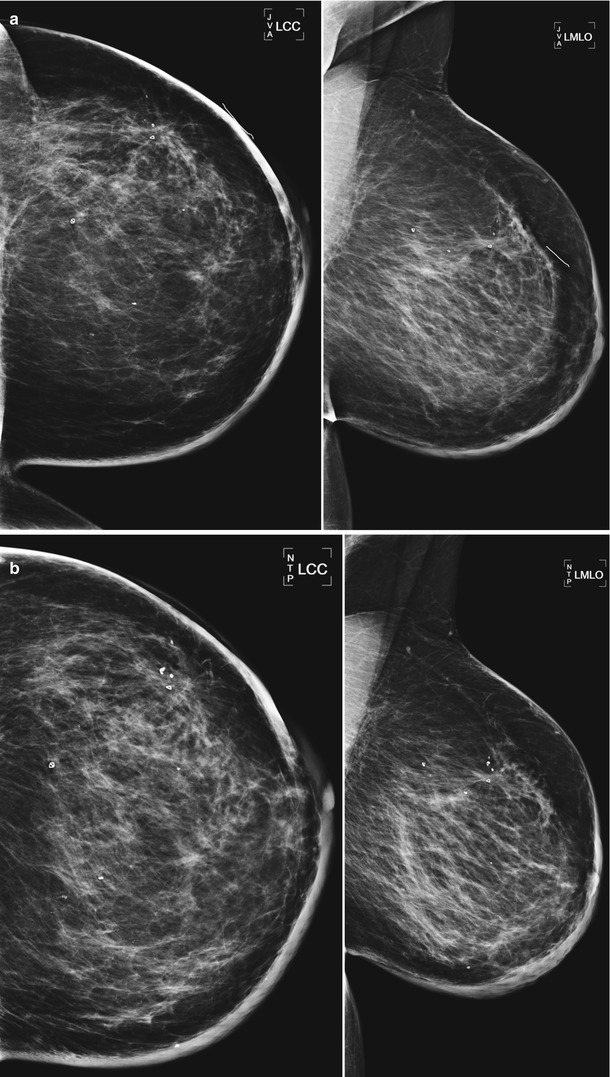

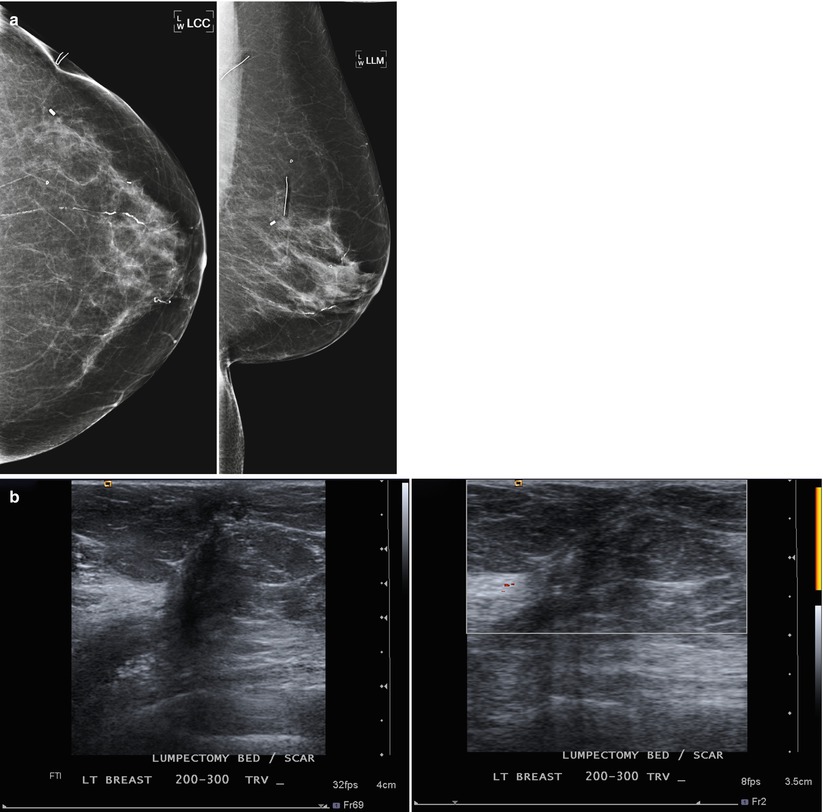

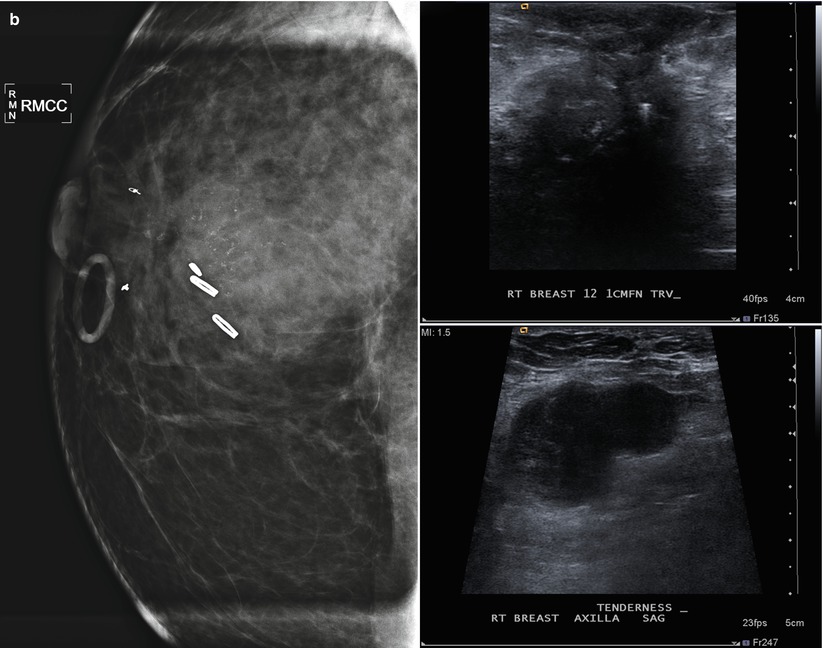

Fig. 16.2

(a) Prior bilateral benign excisional biopsies. Skin scar markers overlie the areas of prior biopsy and correlate to underlying subtle architectural distortion. (b) Note the apparent asymmetry in the posterior upper left breast due to excision of tissue on the right

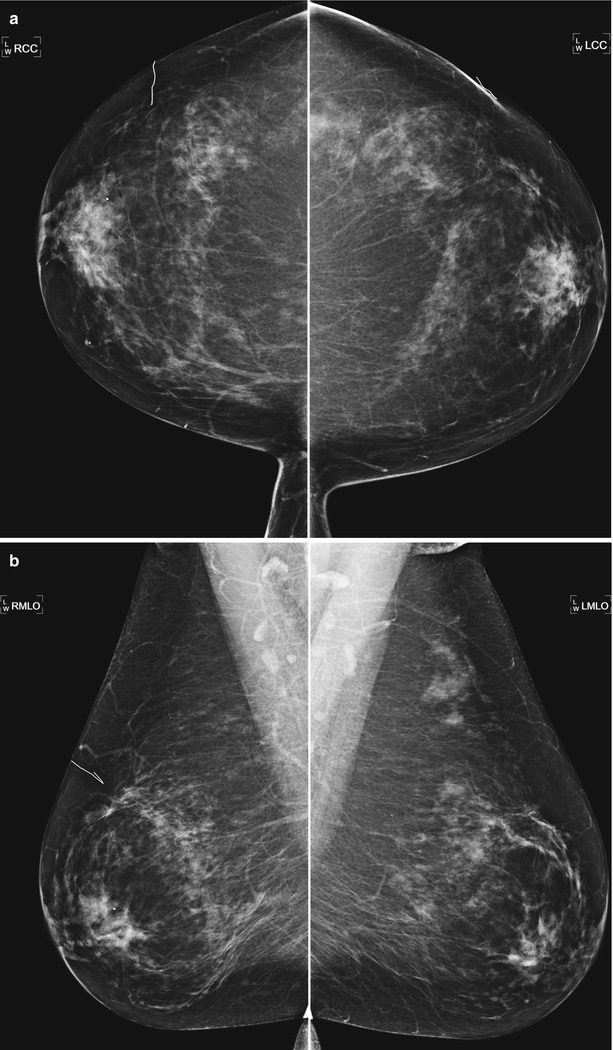

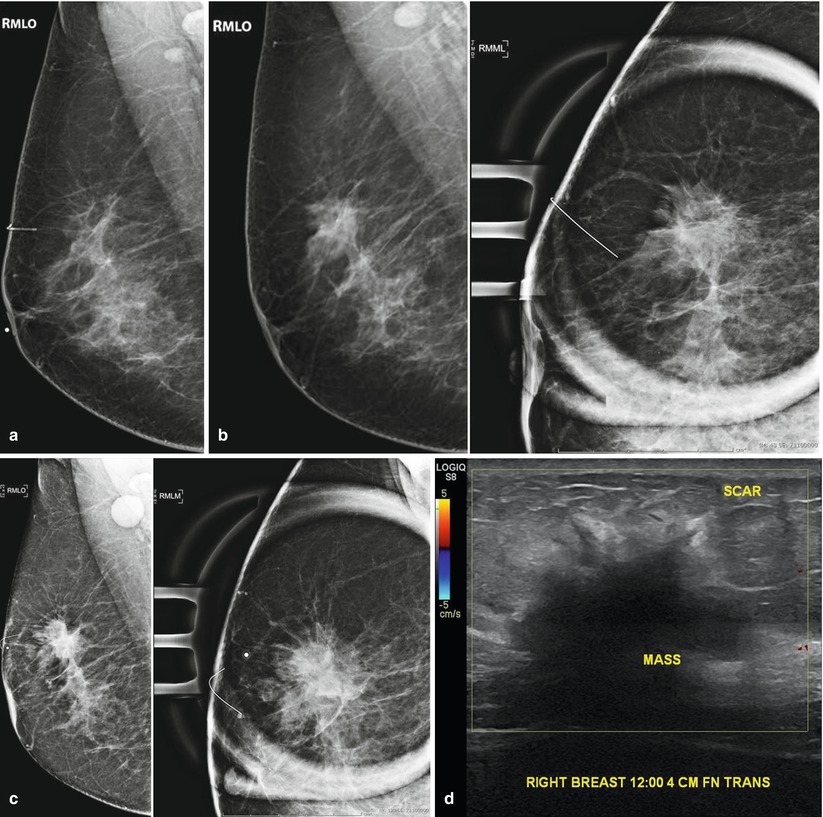

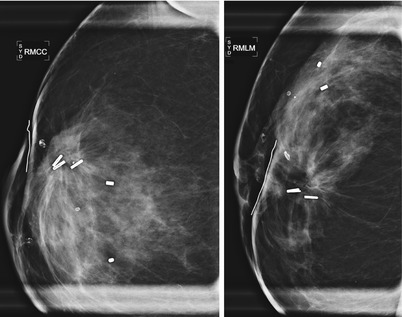

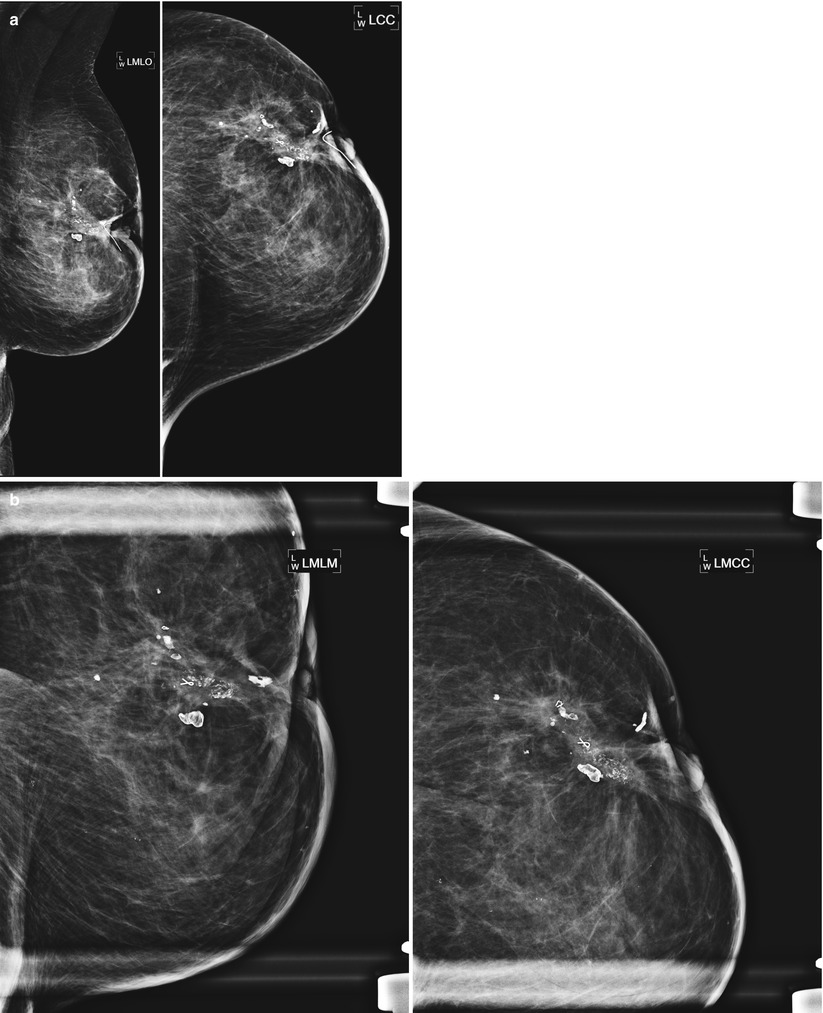

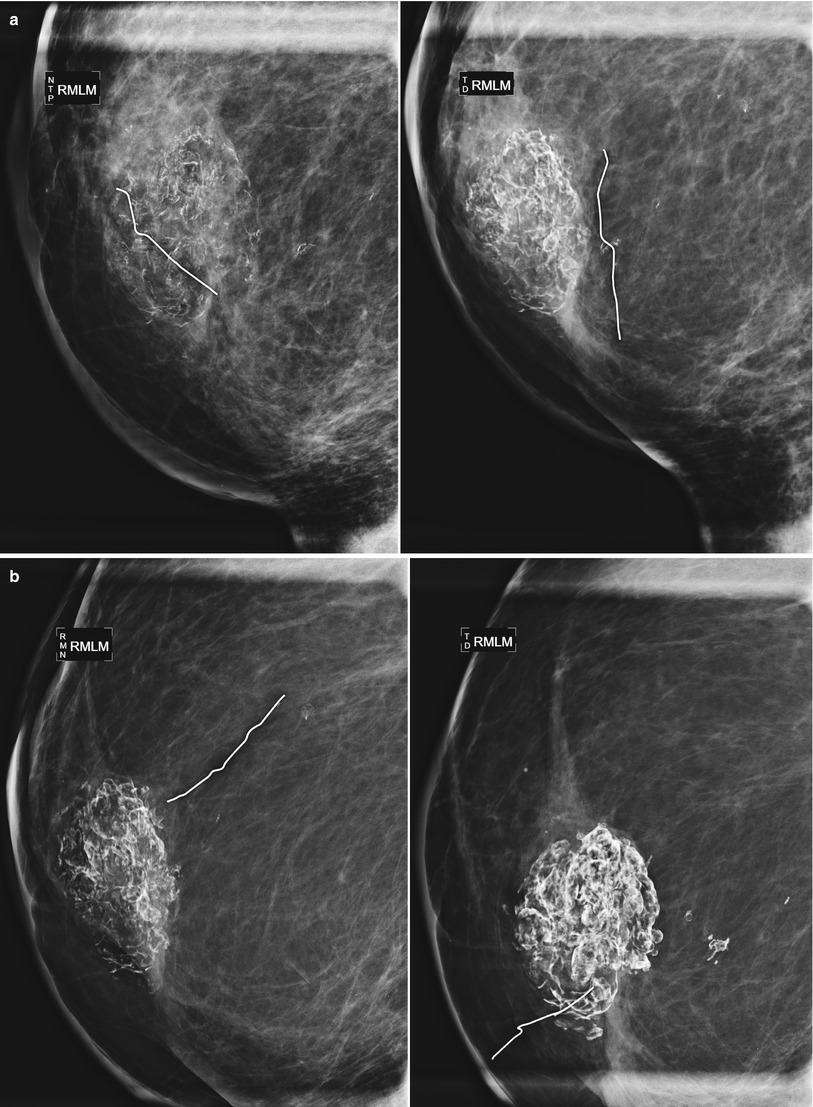

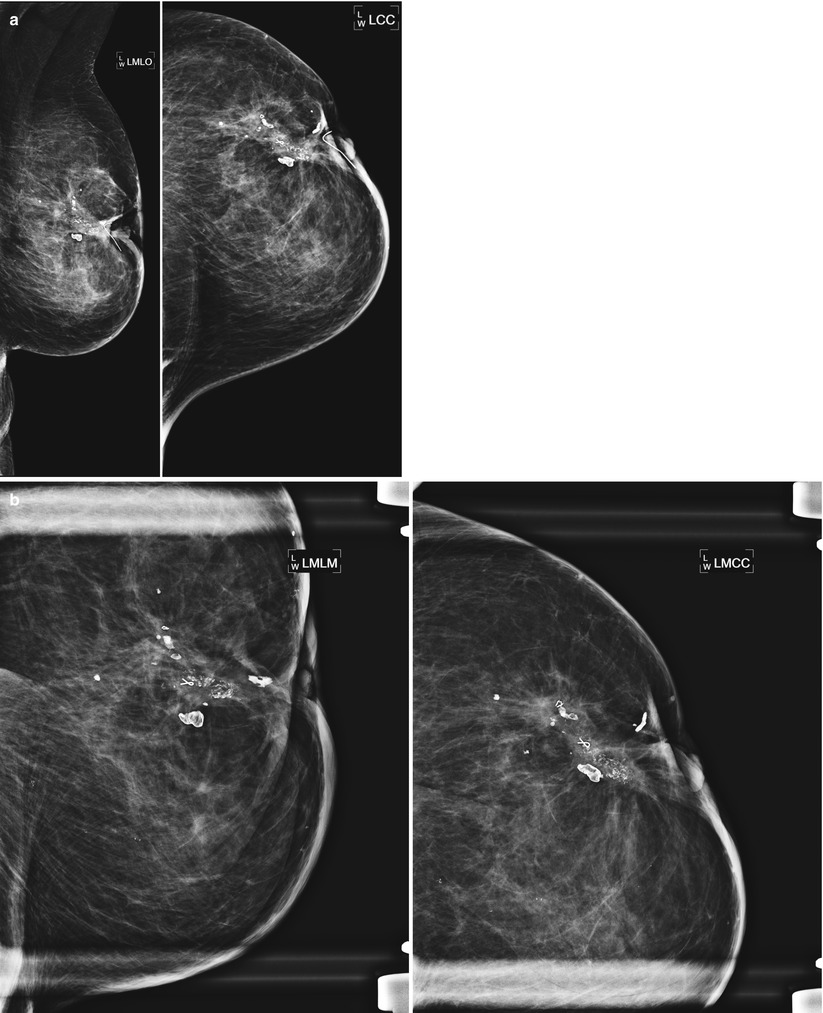

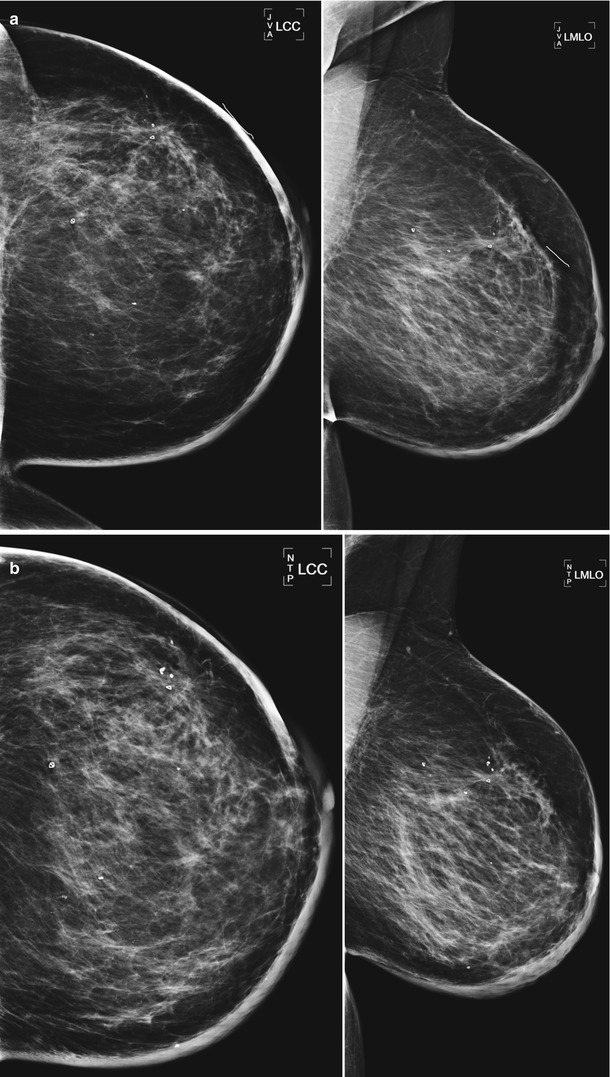

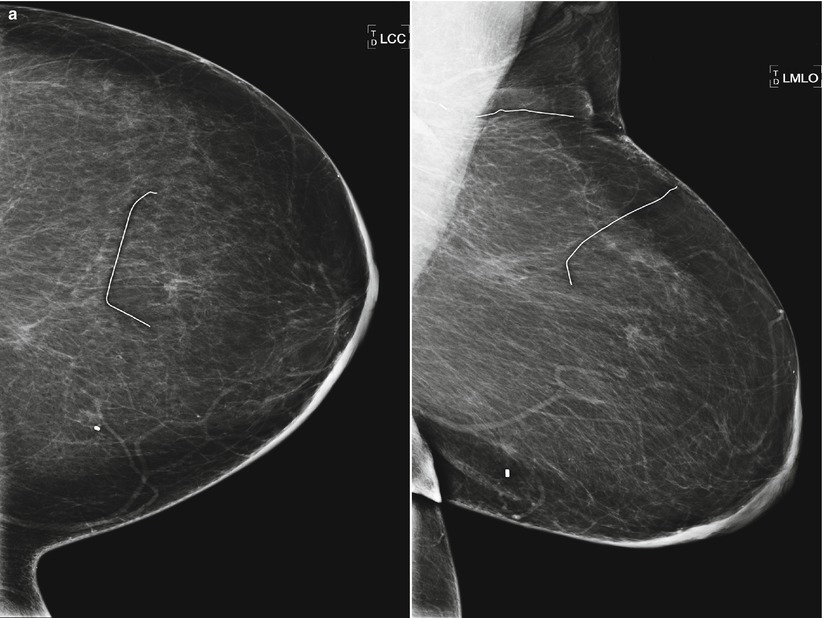

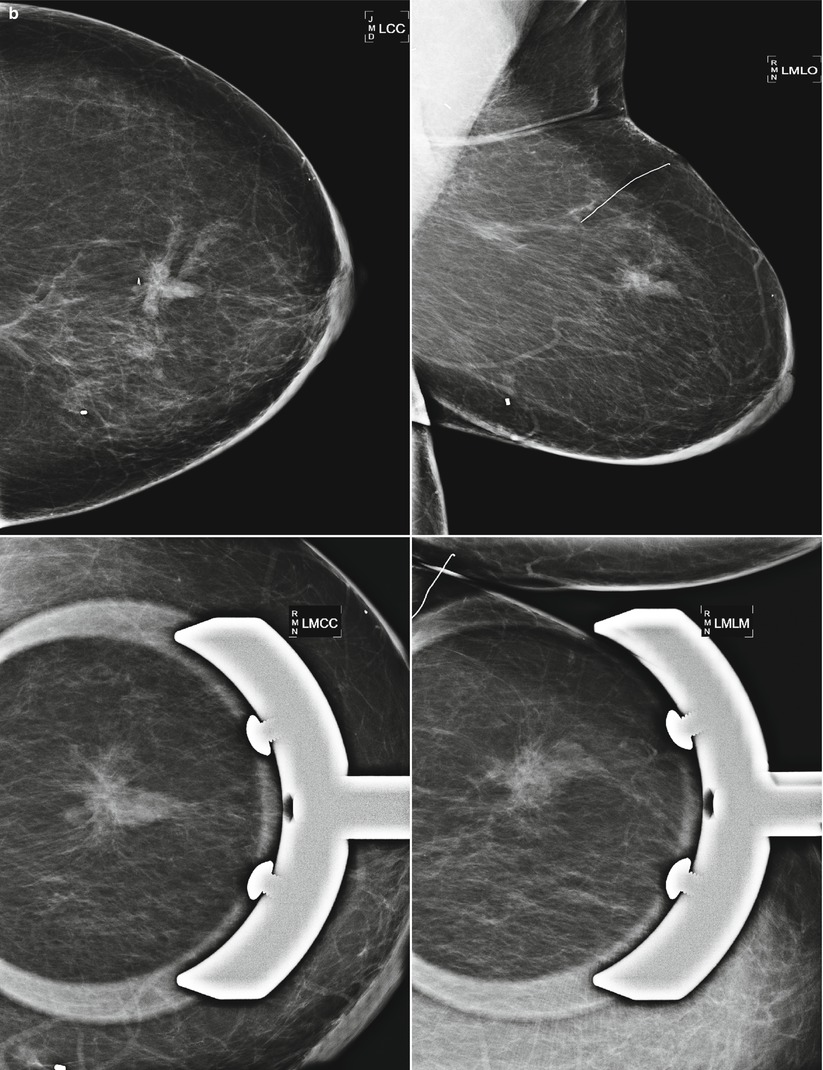

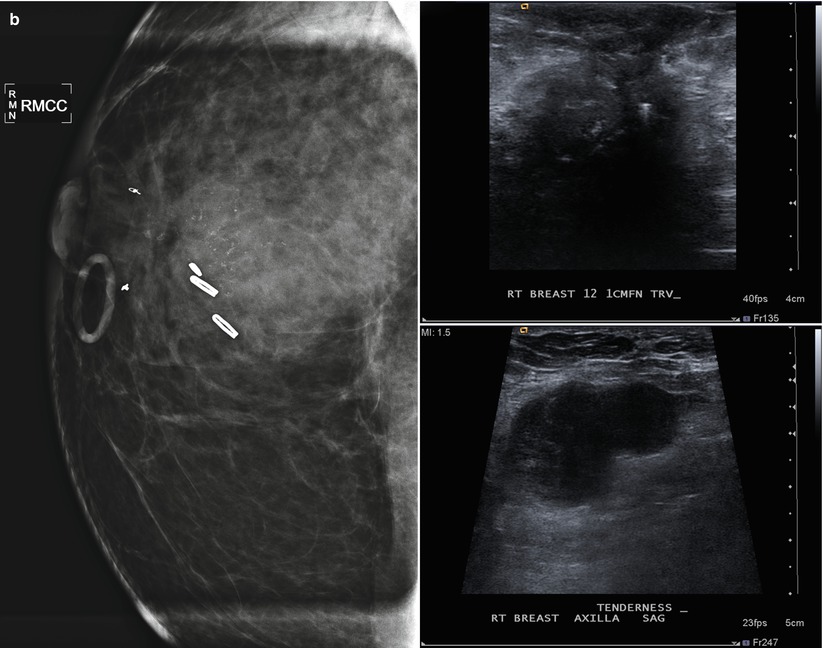

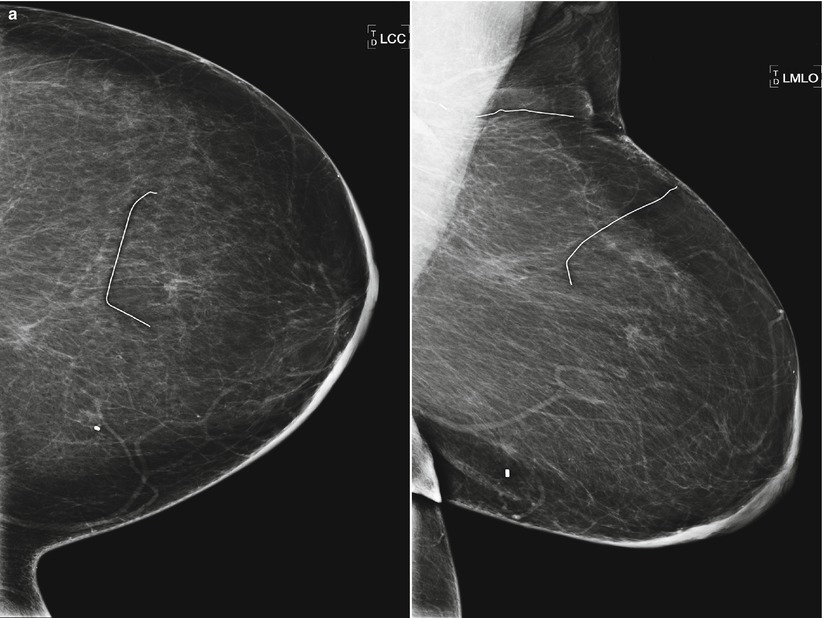

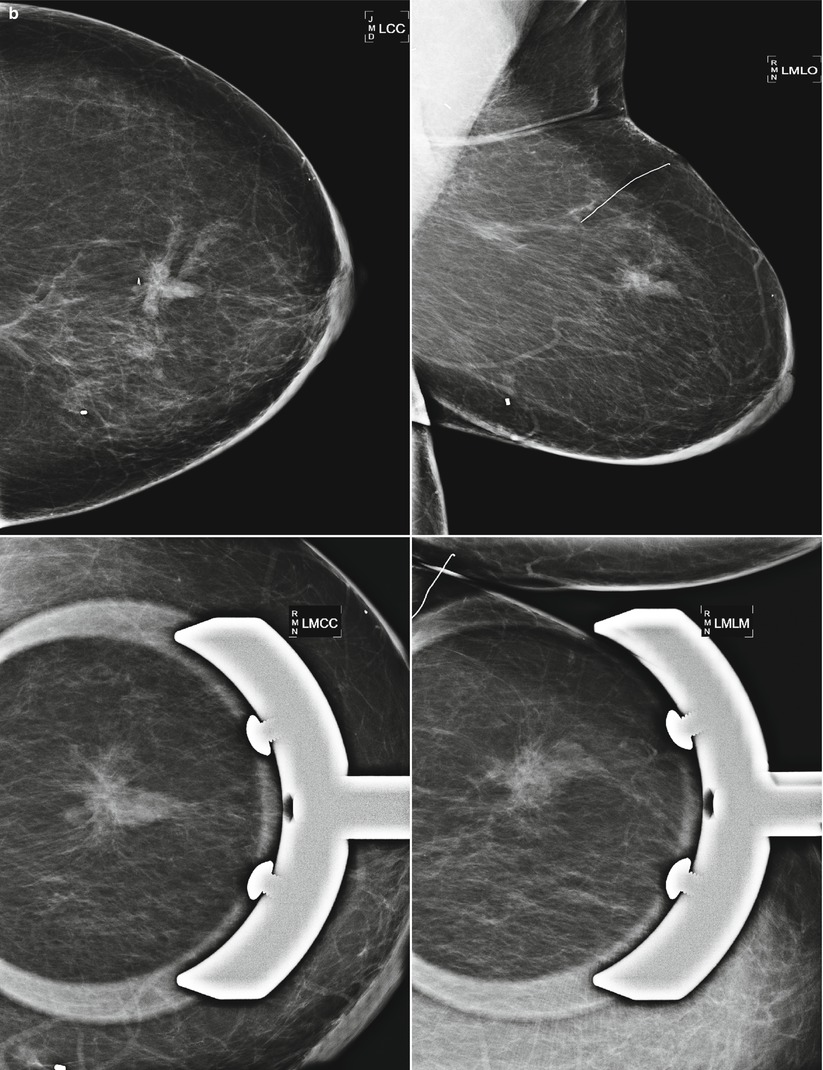

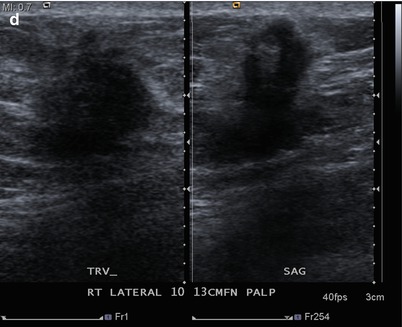

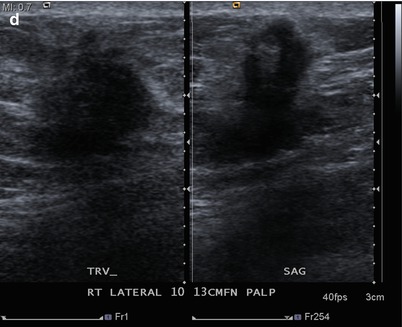

Fig. 16.3

(a) A 73-year-old female status post benign excisional biopsy in the upper outer left breast. Architectural distortion is present in the biopsy bed. (b) Note the apparent asymmetry in the posterior outer right breast due to asymmetric glandular tissue after tissue was removed from the outer left breast

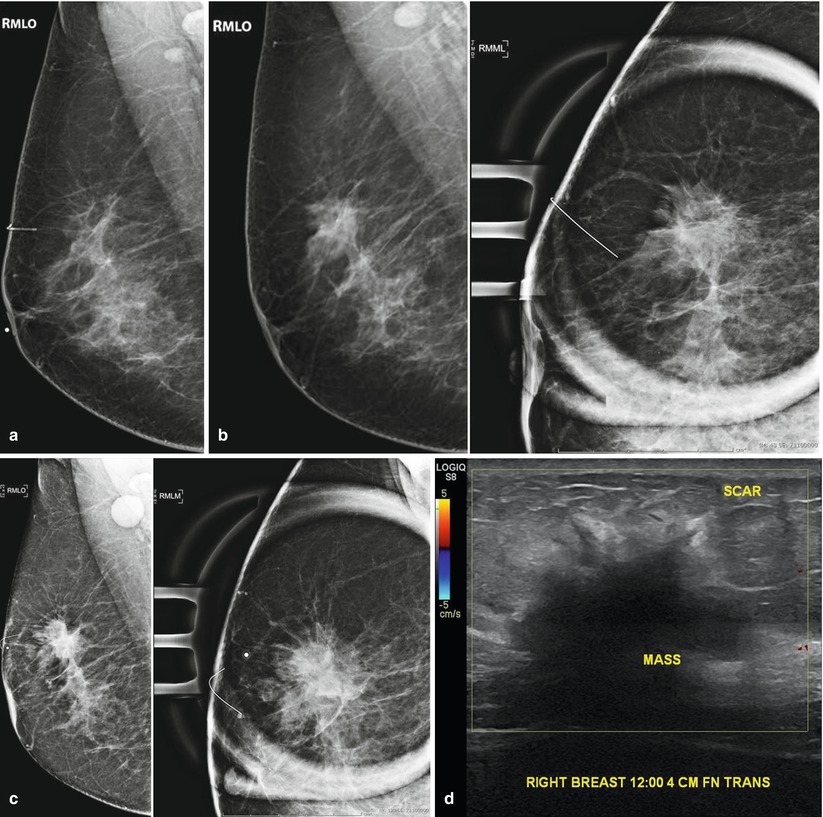

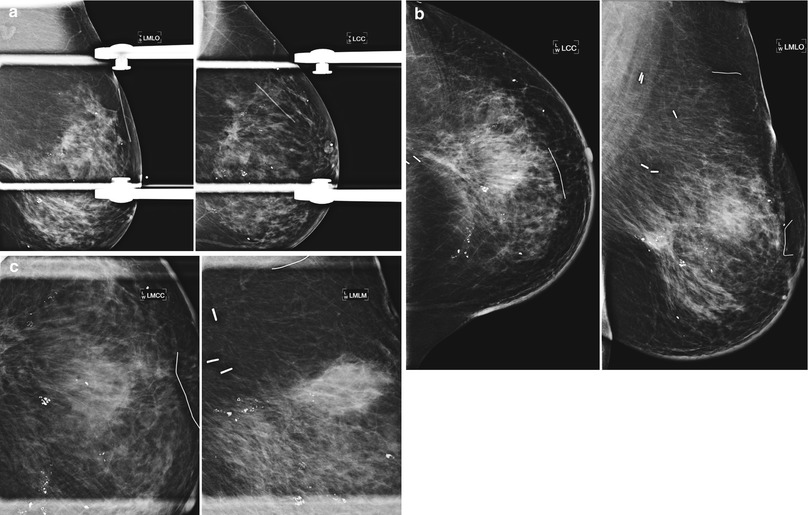

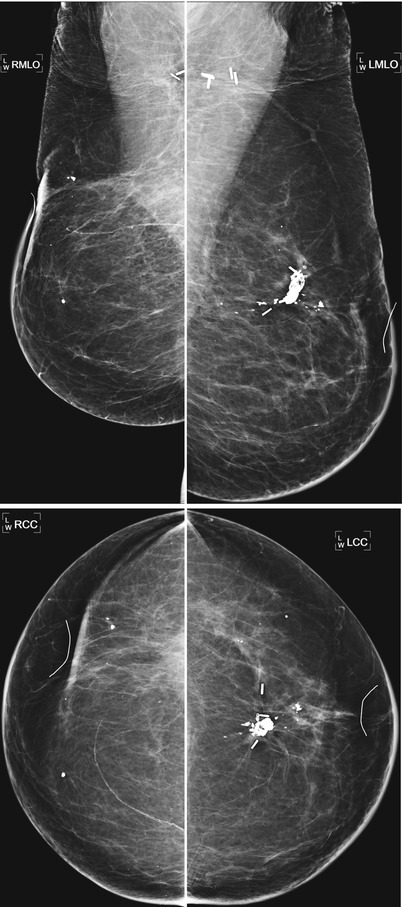

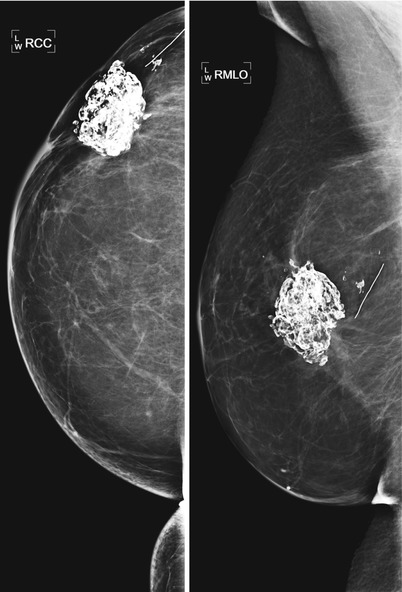

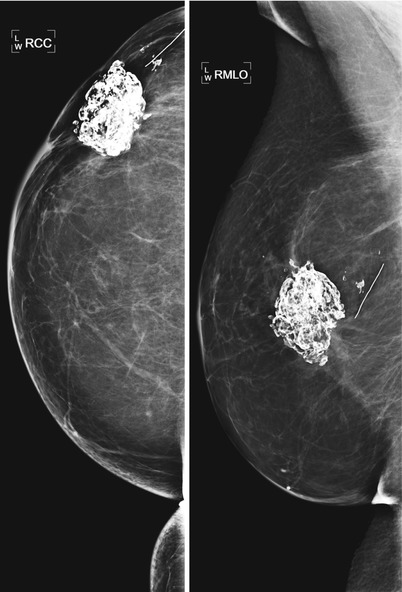

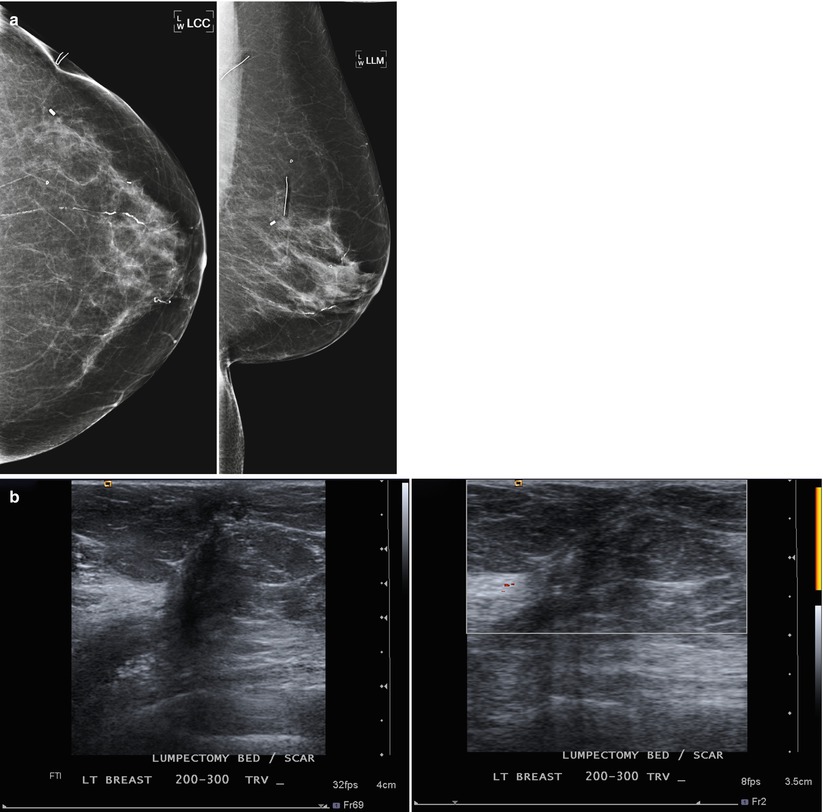

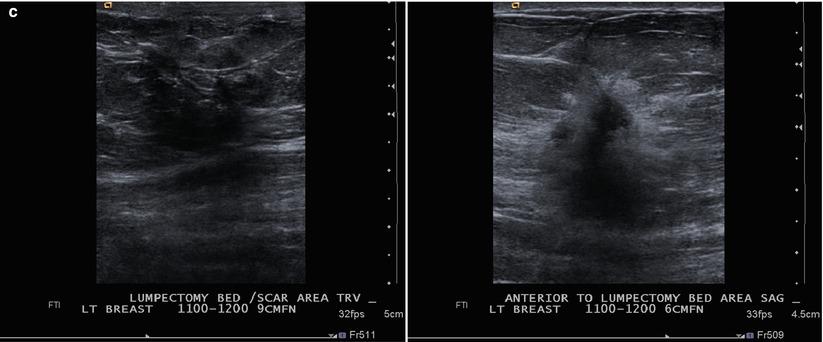

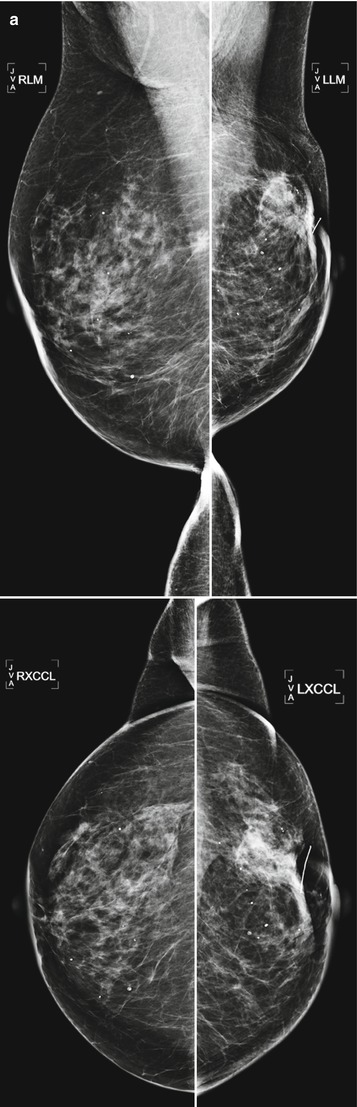

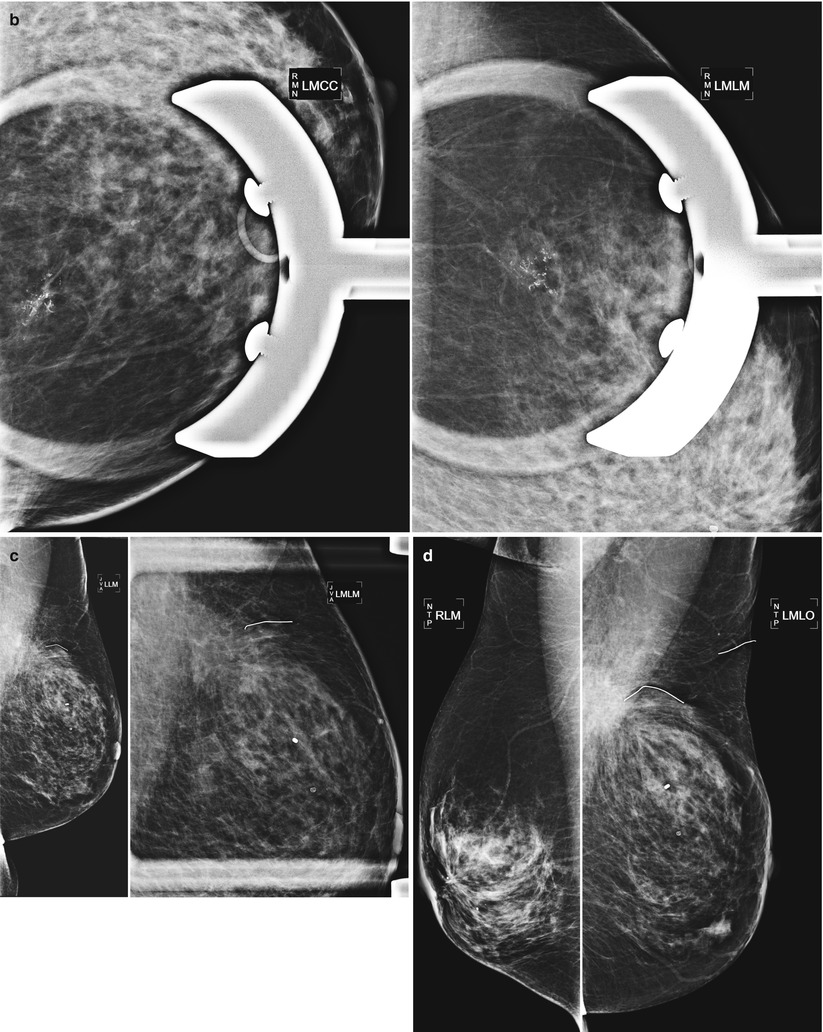

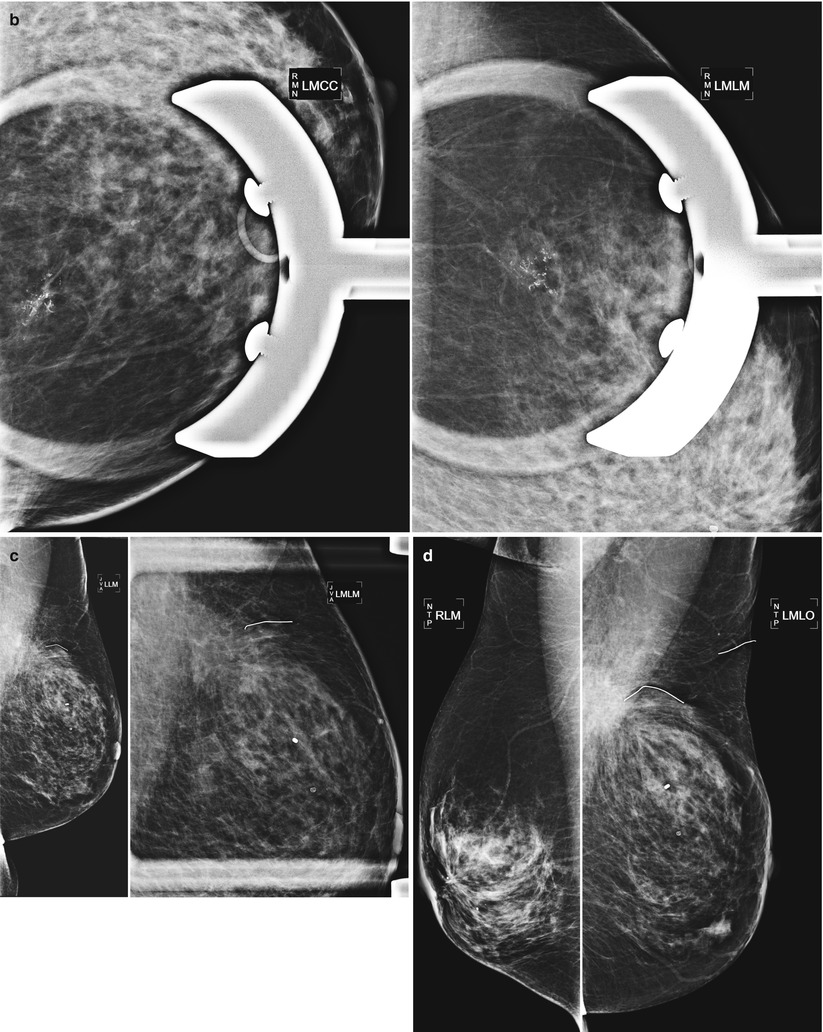

Fig. 16.4

A 59-year-old female status post multiple bilateral benign excisional biopsies. Note mild asymmetry in breast size from more biopsies being performed on the left breast and architectural distortion in the central left breast. A portion of a retained hookwire is present in the posterior medial left breast

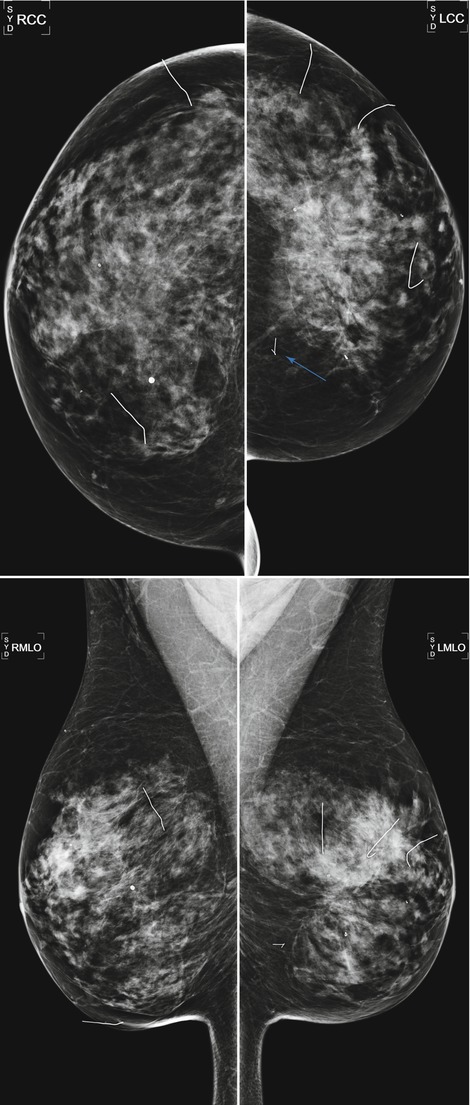

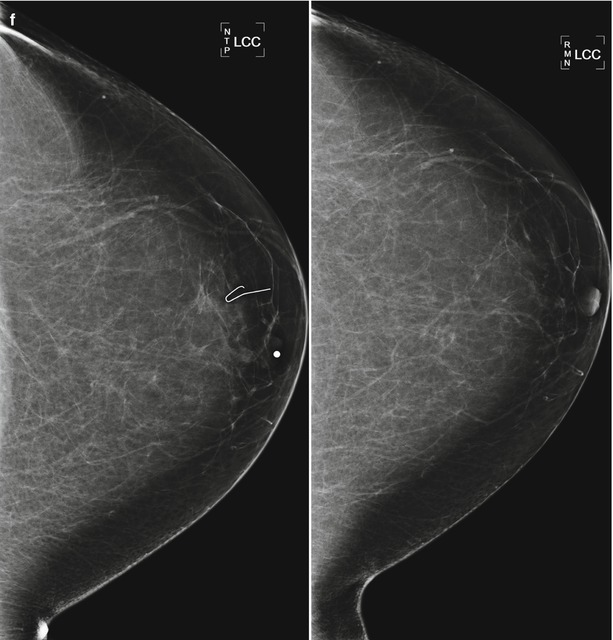

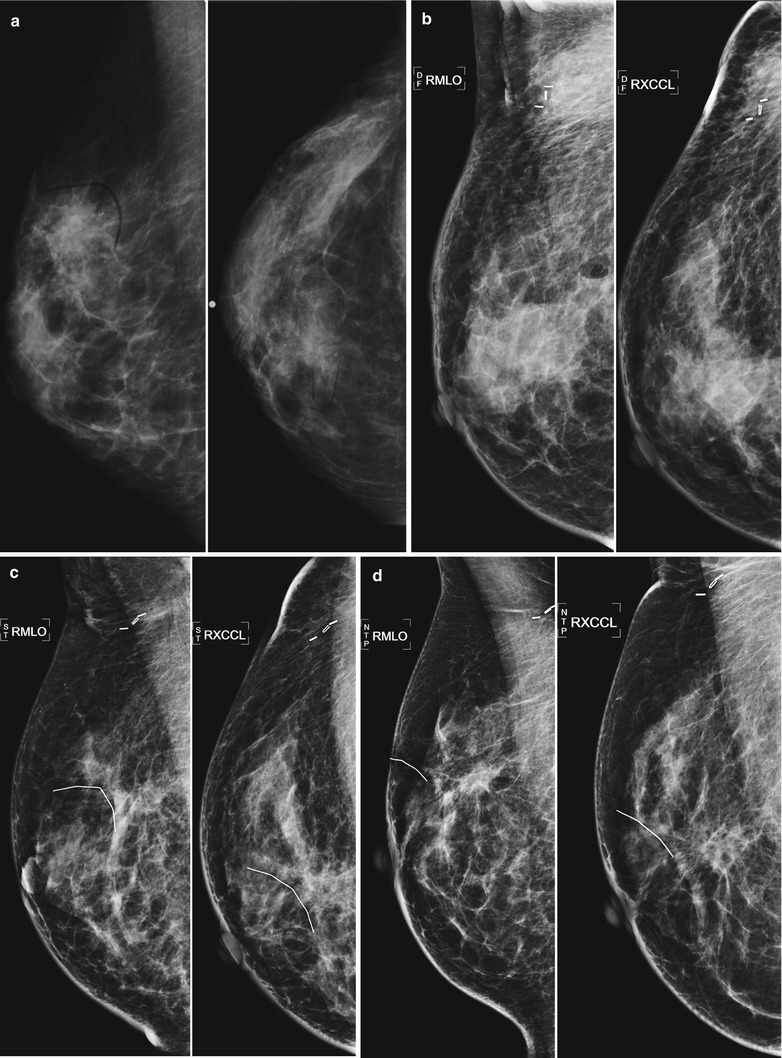

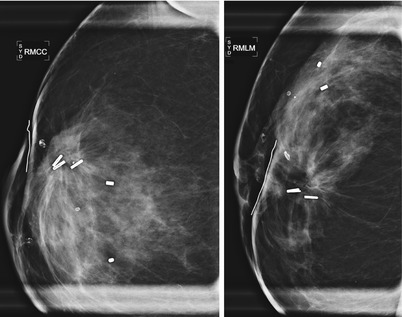

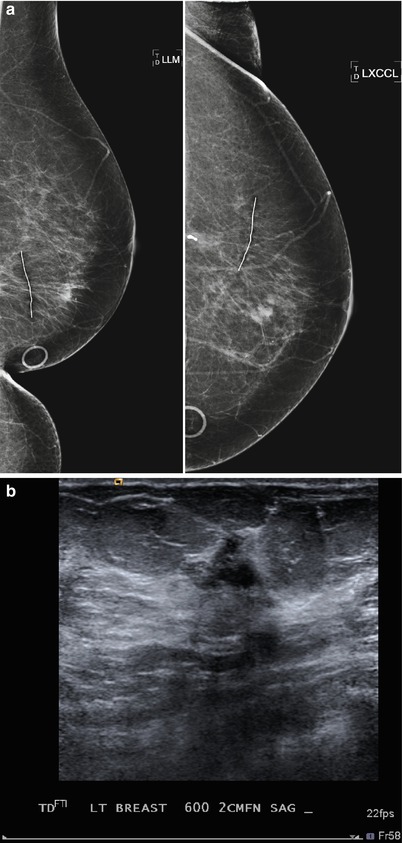

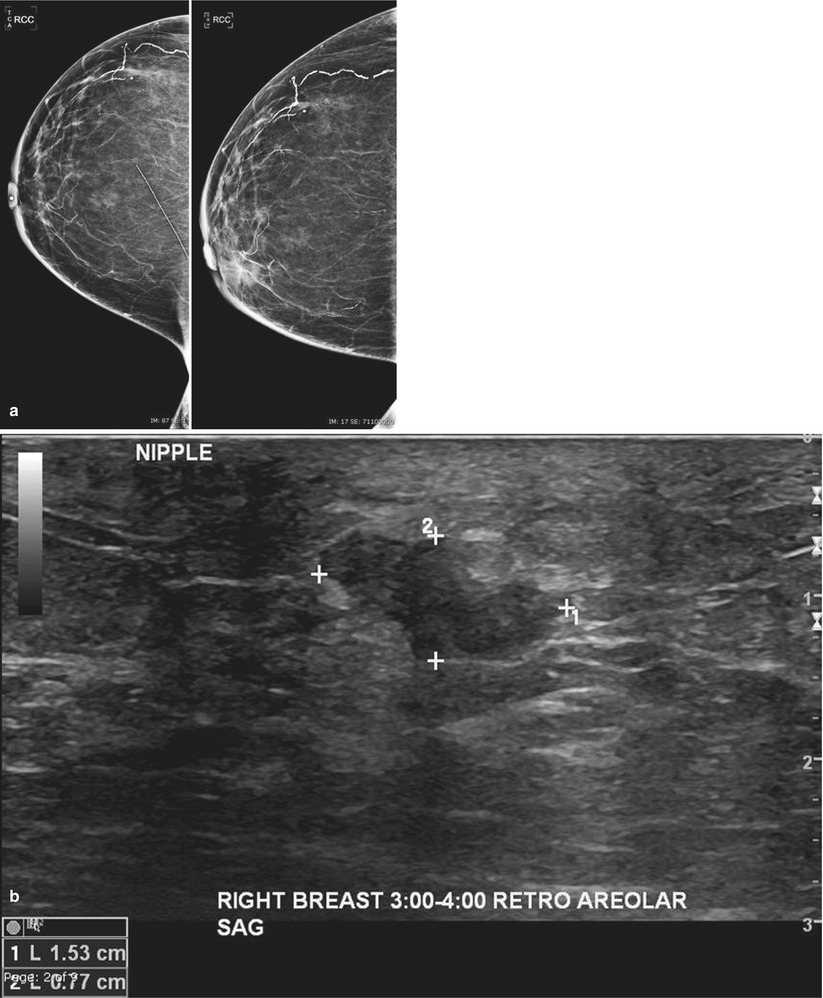

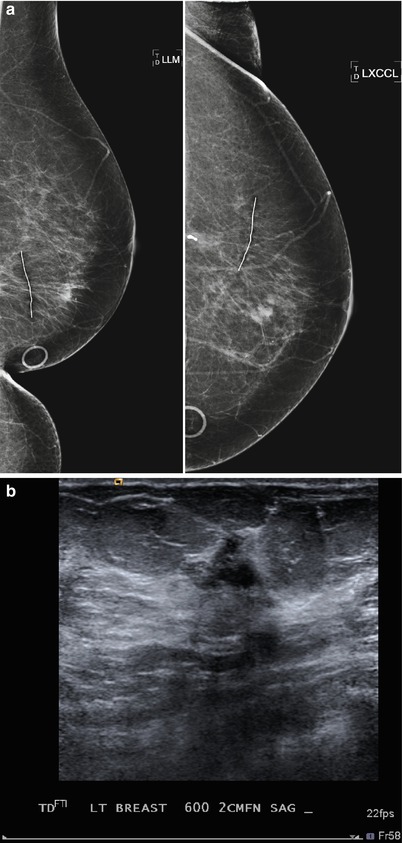

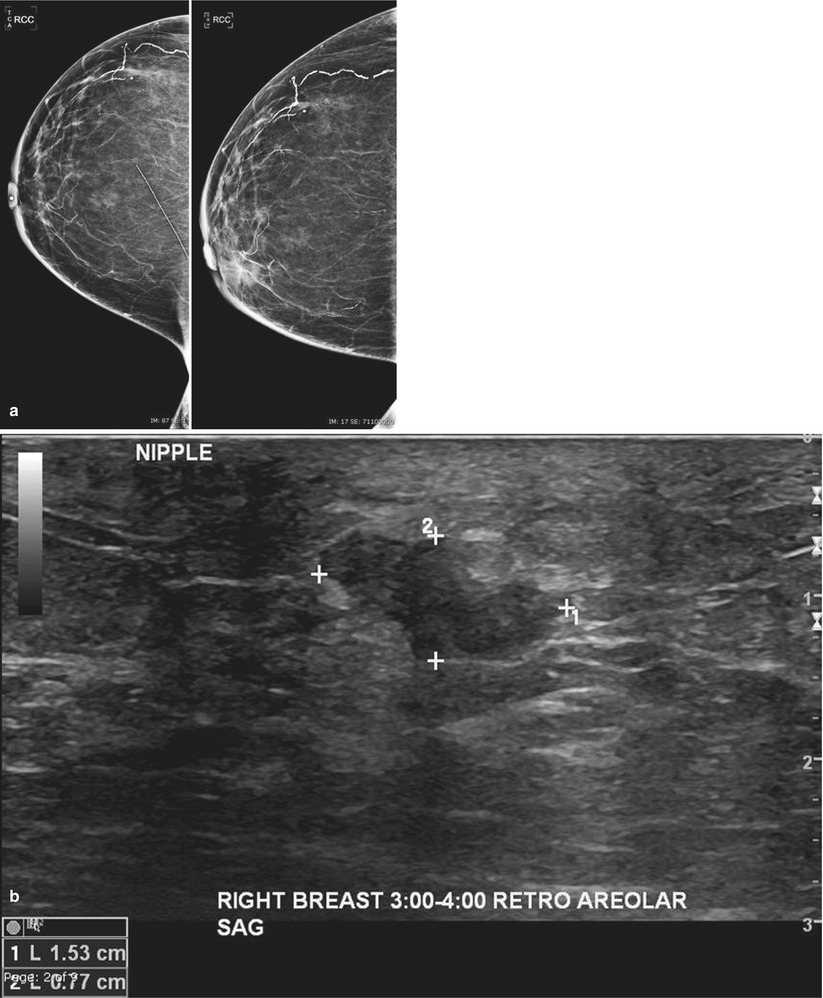

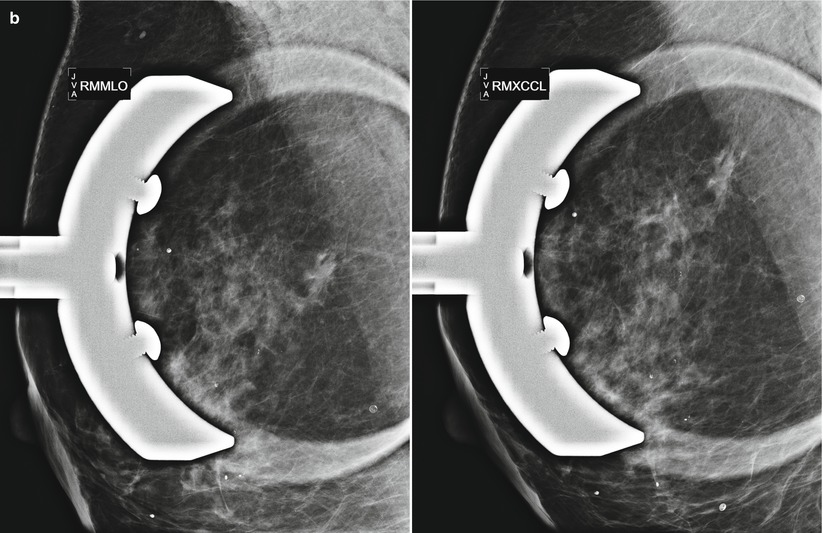

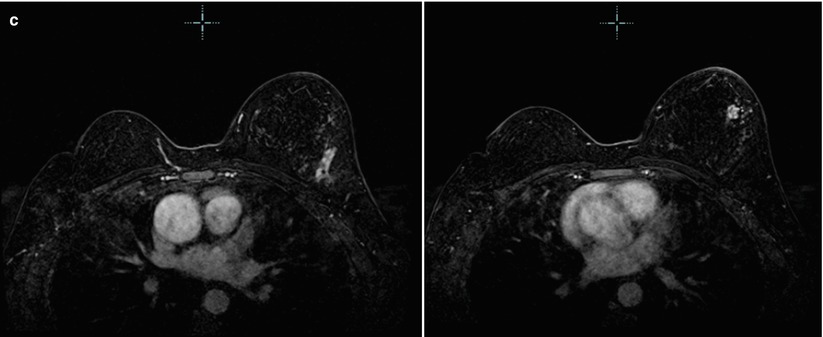

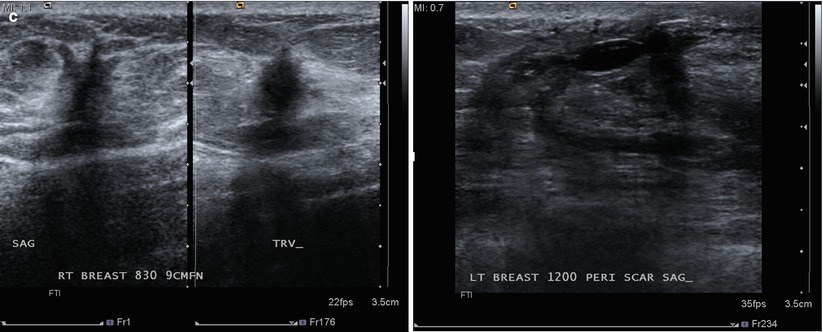

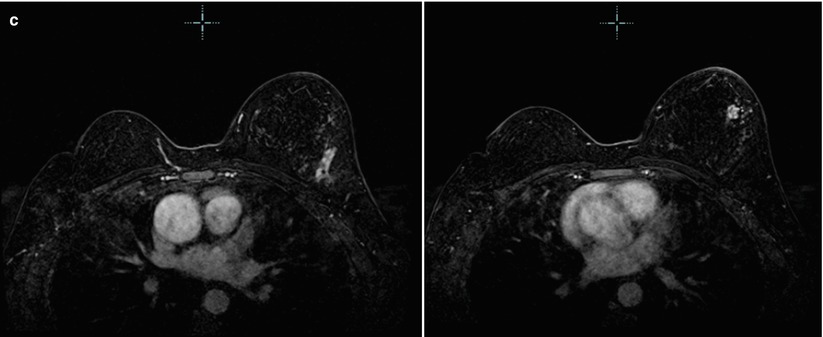

Fig. 16.5

(a) A 65-year-old female with mass in the retroareolar position. (b) Ultrasound demonstrated a corresponding 6 mm intraductal mass. (c) 1 year after surgical excision of benign papilloma. Nodularity in the area of surgery is less conspicuous with spot compression. (d) Ultrasound demonstrated benign scar tissue. No residual or recurrent mass visualized. (e) Follow-up ultrasound performed 6 months (left) and 12 months (right) later shows resolving postoperative findings. (f) Mammogram 2 years (left) and 3 years (right) after surgery demonstrate progressively resolving postoperative changes

Given that both scarring and carcinoma can present as spiculated masses on imaging, clinical history, physical exam, and comparison with prior studies are essential for appropriate management. When there are no prior mammograms available for comparison and when a history of biopsy is not provided, the differential diagnosis should include malignancy, radial scar, and prior trauma in addition to post-biopsy changes. Since there is a possibility for malignancy, if no prior studies are available, additional evaluation with diagnostic imaging is warranted. Technologists should obtain a thorough history of dates of prior surgical biopsies before performing imaging and marking scars in the skin to help avoid confusion. Applying a linear metallic scar marker on the skin can assist in explaining nearby architectural distortion. Some facilities place scar markers routinely while others only place them if there is uncertainty of postsurgical change correlating with a biopsy site. The skin incision can be distant from the postsurgical change, and sometimes it is more helpful to correlate with a preoperative mammogram, if available, as the mammogram will demonstrate the site of original mammographic abnormality where the postsurgical changes would be expected. Architectural distortion distant from a skin marker should be considered suspicious, particularly if the finding is new from prior exams. Review of the patient’s pertinent history and symptoms will assist in increasing accuracy.

While post-biopsy imaging findings require careful evaluation, the challenge of distinguishing post-biopsy change from malignancy is usually more limited than in the post-lumpectomy mammogram given that the risk for malignancy at a site of recent benign biopsy is lower than that of a biopsy performed in a patient with known history of malignancy, particularly in the first few years following biopsy. In a prospective study by Slanetz, mammograms of 1,997 patients presenting for screening were reviewed. One hundred and seventy-three patients reported a prior history of benign biopsy. Fourteen percent (24) of the 173 patients had mammographic evidence of biopsy on the mammogram. Although 5 % (9) of the 173 post-biopsy patients were recalled for additional imaging, none of the recalls were due to confusion or diagnostic concern at the biopsy site. The rate of recall was similar to that of the group without prior history of biopsy. The study concluded that changes from previous excisional biopsy for benign breast problems are uncommon and rarely pose a diagnostic dilemma in interpretation of routine screening mammograms [2]. If there is any concern on the first exam after benign biopsy, a short-term follow-up mammogram can be performed in 6 months. Any increase in calcifications, architectural distortion, or increasing asymmetries on follow-up should prompt biopsy (Fig. 16.6a–d).

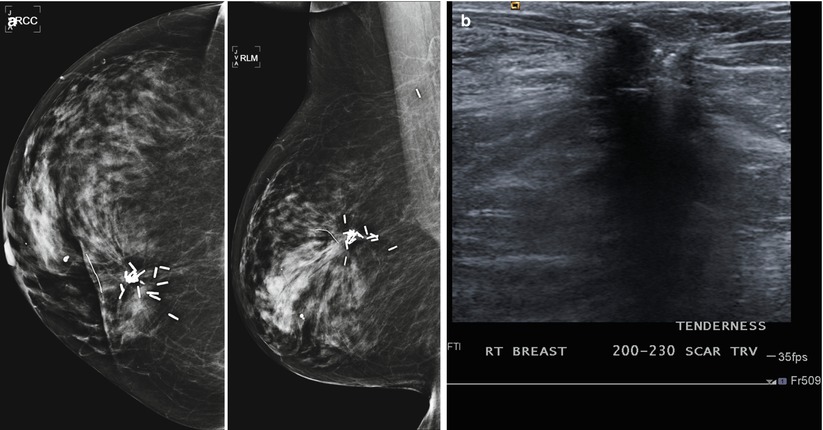

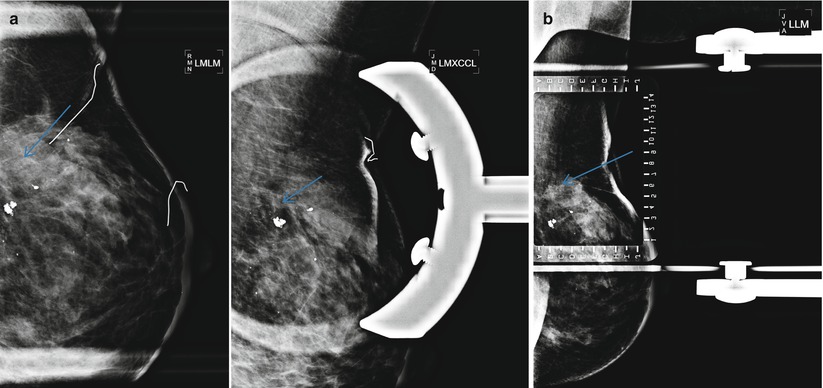

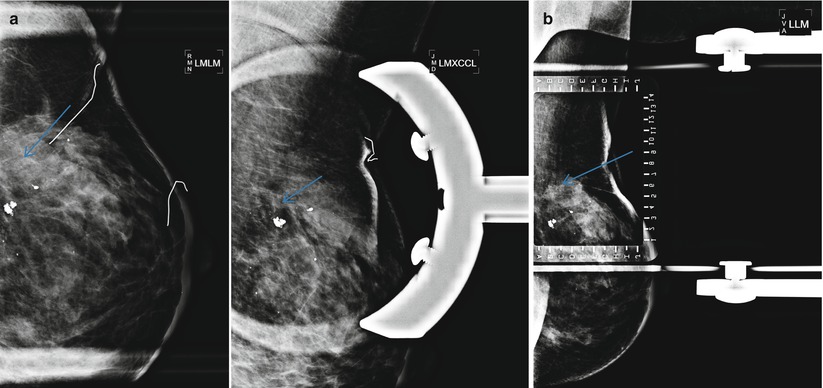

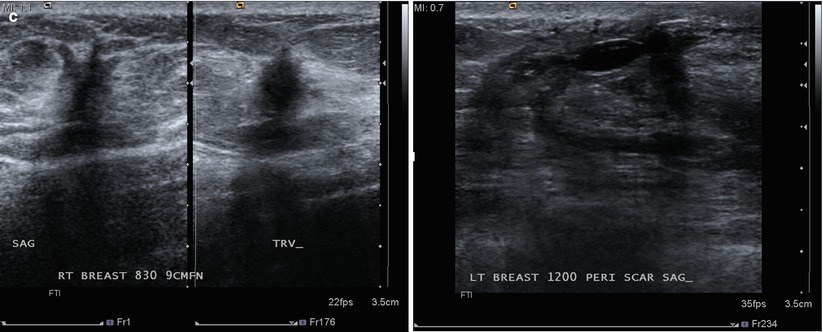

Fig. 16.6

(a) Right mammogram 9 months following excisional biopsy of calcifications. Pathology was benign. Mild architectural distortion is present in the mid upper breast. (b) The patient returns 2 years later. Increased prominence of the glandular tissue in the region of the scar prompted diagnostic mammogram which was interpreted as benign postsurgical change. (c) 7 months later, the patient returned complaining of a palpable abnormality. A high-density mass with irregular margins is visualized. Note enlarged right axillary lymph node. (d) US demonstrates a corresponding 4.2 cm hypoechoic mass superimposed on an area of architectural distortion related to a previous surgical excision site. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma

In some cases, surgical excisional biopsy of an indeterminate or suspicious clinical or imaging finding is performed, rather than image-guided biopsy, and cancer is found at the time of surgery. The margins of the surgical sample are often positive and the patient needs to return to surgery for re-excision and possible axillary evaluation. In these cases, a pre-lumpectomy diagnostic mammogram with spot magnification views of the lumpectomy bed is recommended to evaluate for incompletely resected tumor. Comparison with pre-biopsy mammogram is essential to assess extent of the original disease. Correlation with the pathology report describing what aspect of the biopsy cavity has positive margins is also helpful to direct the imager to give additional attention to these areas. The pre-lumpectomy mammogram is particularly useful in the cases of ductal carcinoma in situ to evaluate for residual calcifications. It is important to recognize that the absence of mammographic findings does not exclude residual disease and lumpectomy is still required despite a negative mammogram. Preoperative breast MRI is also valuable to evaluate for residual disease and to assess for multicentric or contralateral disease in these patients [3–5].

Post-lumpectomy

As the use of mammography and MRI for screening has become more widespread, the detection of early-stage (I or II) breast cancer has increased. Given equivalent survival rates for breast conservation therapy and mastectomy [6, 7] in prospective, randomized trials, lumpectomy with radiation therapy has become the treatment of choice for early-stage breast cancer. Breast conservation therapy achieves local tumor control by surgical removal of the cancer with a margin of normal breast tissue followed by whole breast radiation to try to eliminate any residual microscopic disease that was not evident by radiology, surgery, or pathology.

Imaging plays an important role in evaluating breast cancer patients in both preoperative and postoperative periods. Before surgery, imaging is used to evaluate extent of disease for treatment planning. Following surgery, imaging is used to detect residual or recurrent disease on the affected side and screen the contralateral breast. The imaging challenge in evaluating these patients postsurgery is distinguishing normal benign postoperative and postradiation alterations from tumor recurrence, the imaging findings of which can overlap. The ability to differentiate between the two is usually accomplished by an understanding of expected postoperative findings in correlation with timing since surgery and with evaluation of studies in a temporal context to detect interval changes, sometimes quite subtle.

Presurgical Evaluation

Once a diagnosis of cancer is established by biopsy, review of the mammogram to reevaluate for any possible multifocal or multicentric disease can be performed prior to surgery. Spot magnification view of indeterminate calcifications separate from the cancer and spot compression views of potential satellite nodules adjacent to the cancer or indeterminate masses in distant quadrants can be helpful to exclude additional disease.

As discussed in greater detail elsewhere in this book, breast MRI is also an important tool in the presurgical evaluation of newly diagnosed breast cancer. Multiple studies have demonstrated that MRI detects additional cancer in both the ipsilateral and contralateral breast [8–12]. Use of preoperative breast MRI varies by institution, although by the ACS guidelines breast MRI is recommended in all new diagnoses. A greater extent of the disease is often visualized on these exams.

Post-lumpectomy Evaluation

When postlumpectomy patients return for annual diagnostic imaging, it is helpful to have information on characteristics of the patient’s initial cancer in order to have a better understanding of the features that may increase probability for recurrence. Important tumor features to know include tumor size and grade, proximity of tumor to margins, presence of extensive intraductal component, lymphovascular invasion, and biomarkers. It is also helpful to know if the patient was able to complete radiation and chemotherapy or antiestrogen therapy. Obtaining any prior imaging before reading the mammogram is helpful for comparing the current study to the earliest available postoperative study as detection of subtle progressive changes may not be readily apparent when comparing to exams performed 1–2 years prior. Given that 65 % of tumor recurrences are within a few centimeters of the excision site [13], dedicated attention to the lumpectomy cavity is warranted. One way of providing a more thorough examination of the lumpectomy bed is to perform spot magnification views of the surgical site. At our institution, we routinely perform these additional views for the first 5 years following surgery, although there is no published consensus on this practice.

Accurate interpretation of the postlumpectomy mammogram involves detection of potential recurrence as early as possible while limiting misinterpretation of postsurgical change as tumor recurrence. Diagnostic accuracy will be increased by familiarity of timing of tumor recurrence and expected chronological posttreatment changes. These changes include edema and skin thickening, masses and fluid collections, scarring and architectural distortion, and calcifications. These are the post-biopsy changes at the surgical site (previously discussed) with added diffuse skin thickening and breast edema associated with breast radiation. The changes seen after lumpectomy are usually more profound and prolonged than those seen after benign excision (Fig. 16.7). In comparison to the changes seen in the postlumpectomy breast, the changes following excisional biopsy usually resolve more quickly and, on occasion, completely.

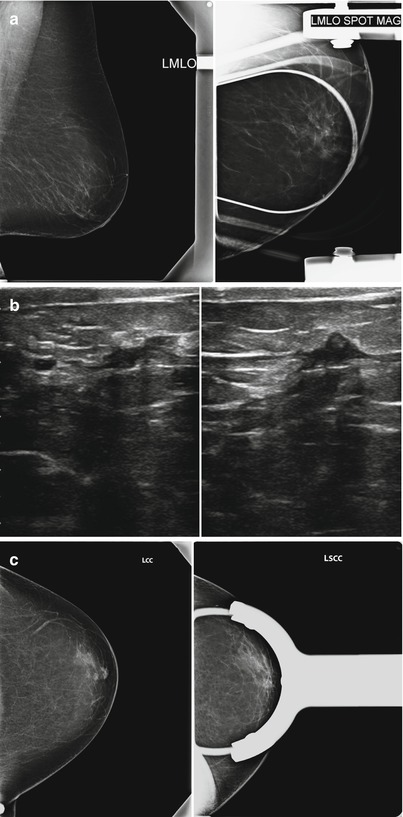

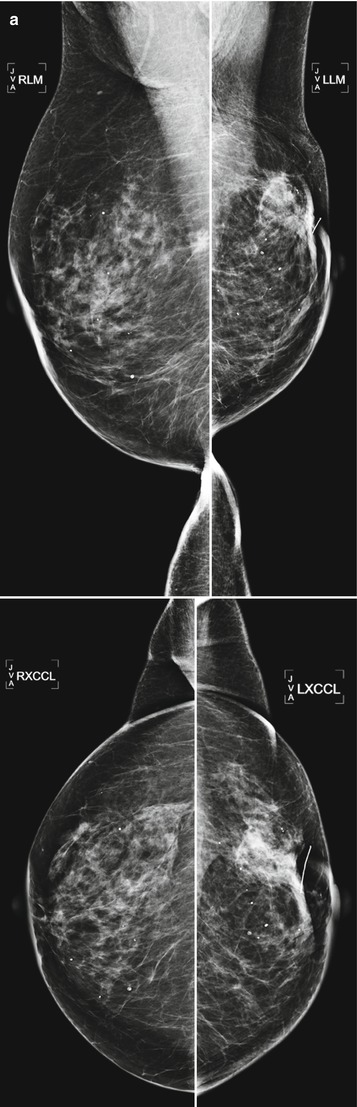

Fig. 16.7

Routine annual exam in a patient who underwent left lumpectomy and right breast excisional biopsy at the same time, 8 years prior to the exam. Note greater volume loss and postsurgical clips at the site of lumpectomy

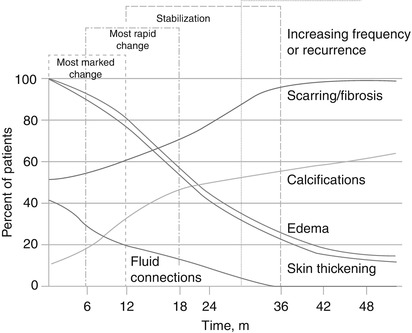

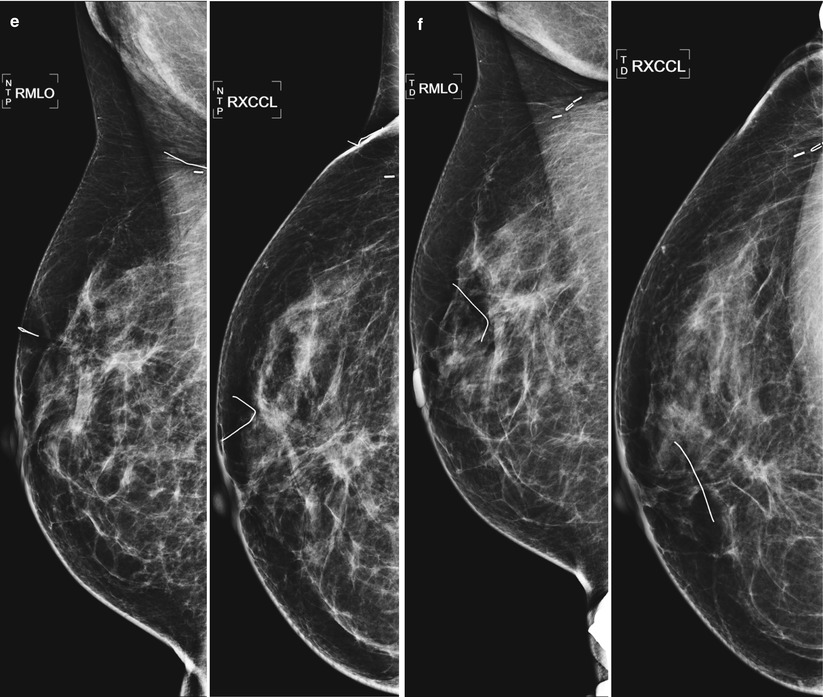

Mammography performed 6–12 months after lumpectomy will demonstrate the greatest post-procedural changes [14]. The appearance of expected post-lumpectomy findings is dependent on the size of the lumpectomy and the time that has elapsed since the surgery (Figs. 16.8a–f and 16.9). Mendelson summarizes the expected time course for changes in the conservatively treated breast in the following chart (Fig. 16.10).

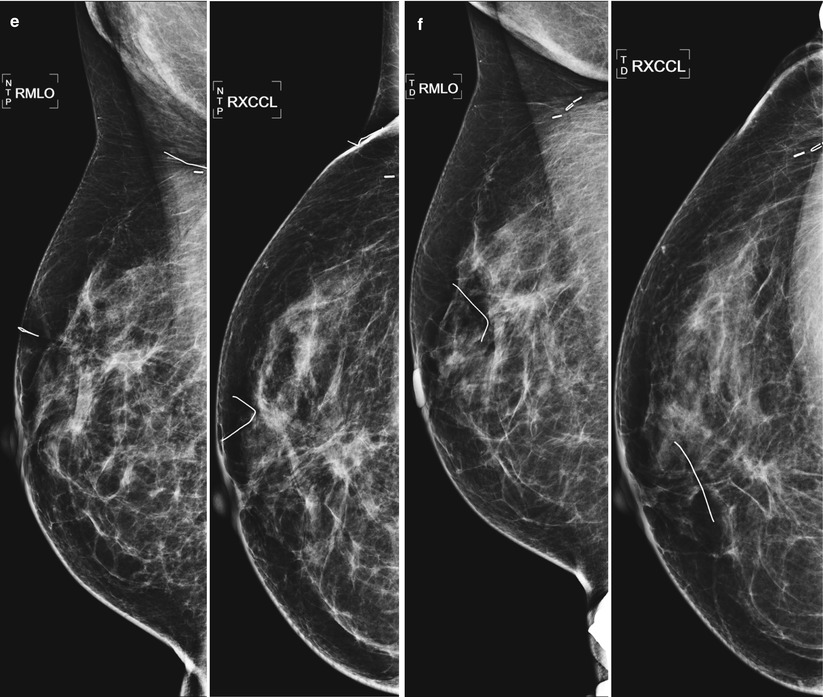

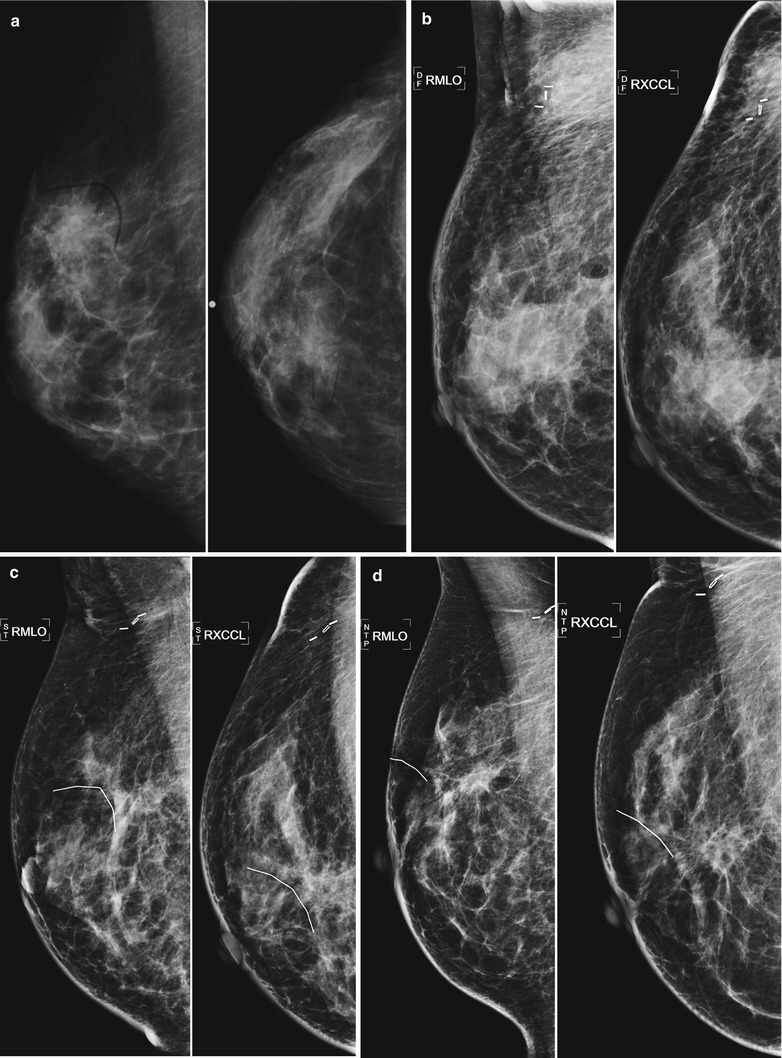

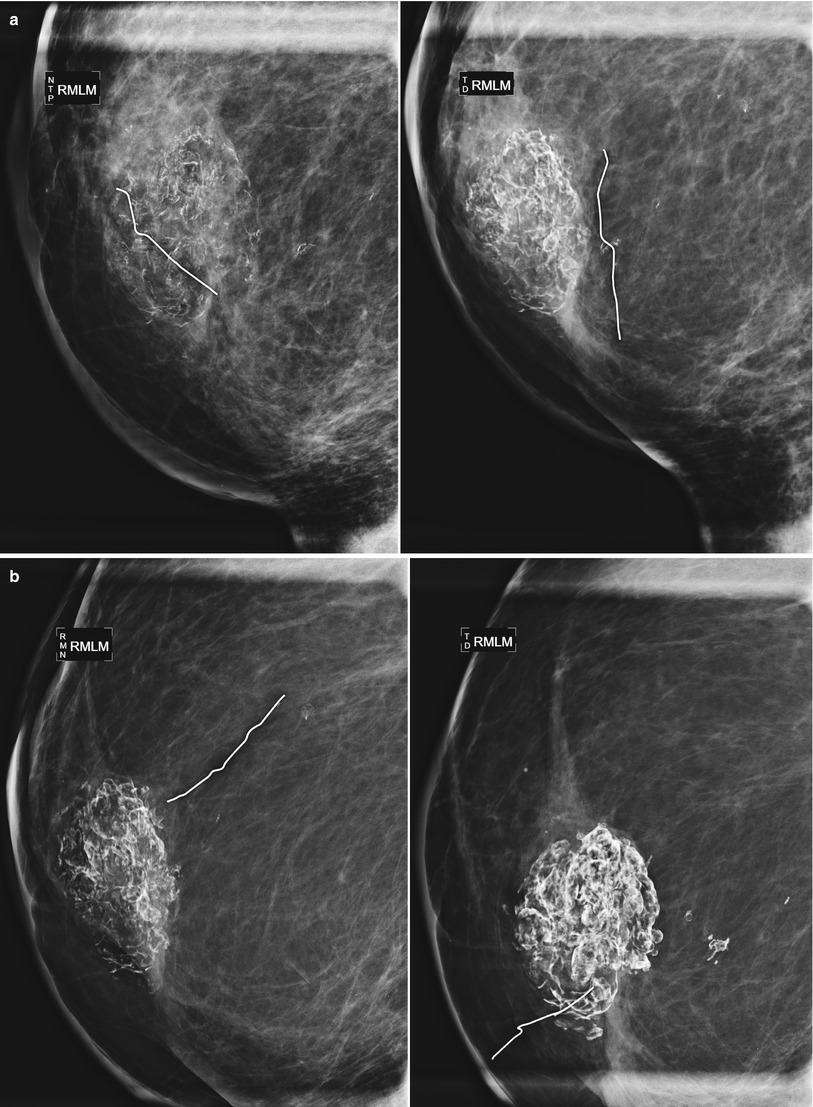

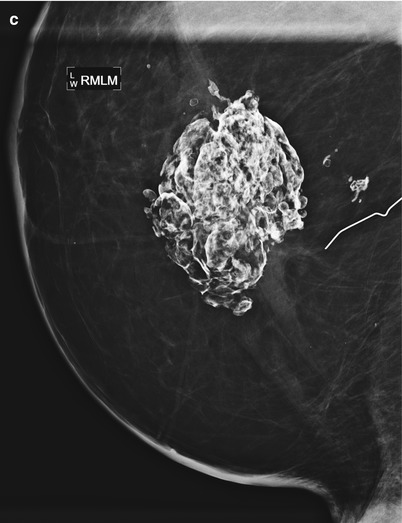

Fig. 16.8

(a–f) Progressive chronological changes in the lumpectomy cavity. (a) A 58-year-old with new spiculated mass in the upper inner right breast. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma. (b) The patient presented to our clinic 12 months following lumpectomy. (c) 18 months following lumpectomy. (d) 24 months post lumpectomy. (e) 36 months post lumpectomy. (f) 5 years post lumpectomy with continued decrease in edema and scarring

Fig. 16.9

Minimal postsurgical change (left) 3 years after lumpectomy for a small area of DCIS. Note the absence of findings in the axilla as no axillary dissection was performed. Compare with more significant distortion (right) in another patient 3 years following a more extensive lumpectomy

Fig. 16.10

Chronological change in appearance of the breast following lumpectomy (Used with permission from Mendelson [18])

As demonstrated in the chart, breast edema and skin thickening are post-treatment changes with similar time courses after surgery. Breast edema manifests as skin and stromal thickening, trabecular thickening (engorgement of intramammary lymphatics) and diffusely increased breast parenchymal density [15]. The increased parenchymal density may be due to attenuation of the x-ray by edematous tissues and fibrosis and perhaps in part due to less compression secondary to patient discomfort. Initially the breast may appear enlarged due to edema. These changes are most prominent in the periareolar and dependent areas of the breast and will make the breast less compressible. Breast edema and skin thickening are particularly apparent when comparison is made with pretreatment mammograms by doing direct comparison with the contralateral breast. As the edema resolves, usually within the first 2 years after treatment, the breast will progressively decrease in size and the breast parenchyma will retain an increased density due to loss of volume and radiation fibrosis. If breast edema recurs or increases after stabilization, differential considerations include lymphatic spread of cancer, obstructed venous drainage, congestive heart failure, and infection [14].

Architectural distortion in the lumpectomy bed may be due to parenchymal scarring, fat necrosis, or recurrent cancer (Fig. 16.11a, b). The best way to discriminate scarring and recurrence on mammography is careful temporal evaluation. Scars contract and decrease in size as they mature and stabilize [14]. Radiolucent fat can be seen interspersed within the spiculated soft tissue of the scar. Mammographic findings suggestive of recurrence include lack of central radiolucent areas, new skin retraction, and increase in size, density, or nodularity of the scar [16].

Fig. 16.11

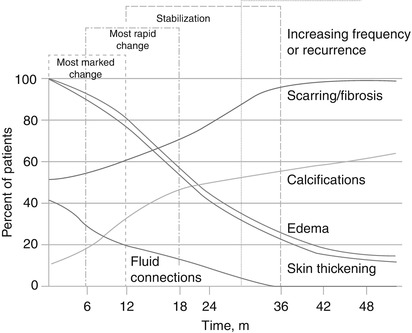

(a) A 69-year-old female status post lumpectomy 12 years prior to exam. Post-lumpectomy changes are present in the upper inner right breast including surgical clips deployed at the margins of the lumpectomy site to focus follow-up mammography and to guide radiation planning. (b) Ultrasound of the area of prior lumpectomy shows expected sonographic findings of scar tissue

Various fluid collections can develop following surgery including hematomas, seromas, and less commonly abscesses (Fig. 16.12a–c). These fluid collections may present as palpable or mammographically detected radiodense masses in the first year after breast conservation therapy [17]. Mammography will demonstrate postoperative fluid collections in 50 % of patients at 4 weeks and in 25 % of patients at 6 months after surgery [18]. Fluid collections are better evaluated with ultrasound and will be discussed in greater detail in the section on sonographic evaluation post lumpectomy. Most postoperative fluid collections resolve by 12 months.

Fig. 16.12

(a) An 80-year-old female with new 7 mm irregular mass in the posterior upper central left breast. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma. (b) 6-month follow-up after lumpectomy. (c) Spot magnification views of the lumpectomy bed. Focal increased density likely represents a resolving postoperative fluid collection. Scattered benign-appearing coarse calcifications are present

Evaluation of newly developing calcifications in the postlumpectomy mammogram is of particular importance because often recurrences that present this way are not clinically detectable and provide an opportunity for early detection [13]. From a temporal standpoint, it is common for new calcifications to form in the lumpectomy bed within the first year after surgery in up to 28 % of cases [18]. Given that the risk of recurrence is greatest starting 2–3 years after surgery, most studies assign a low probability of malignancy in calcifications that occur within the first 18 months after surgery and radiation. Although most newly occurring calcifications in the postsurgical breast are benign, calcifications in post-treatment mammograms in patients with history of invasive carcinoma with extensive intraductal component or large areas of comedonecrosis should be approached with a higher level of suspicion as these tumors have higher risk of recurrence [18].

Calcifications at the lumpectomy site should be assessed in the same manner calcifications on routine screening mammograms are evaluated: calcifications with suspicious morphology or distribution increase the probability of malignancy and should prompt biopsy. The majority of calcifications that develop after surgery will be benign fat necrosis, dystrophic calcifications, or calcifying suture material (Figs. 16.13, 16.14, and 16.15). Magnification views are required to distinguish these benign calcifications from suspicious pleomorphic calcifications of cancer recurrence. Benign oil cysts present as thin rims of calcifications around a radiolucent center.

Fig. 16.13

Stable architectural distortion and benign calcifications 5 years post lumpectomy

Fig. 16.14

Bilateral lumpectomies 9 years prior. The left breast shows benign fat necrosis, while the right breast has greater volume loss and architectural distortion

Fig. 16.15

Patient had left lumpectomy 3 years prior to exam. A new 5 mm cluster of heterogenous calcifications is visualized in the lumpectomy bed. Stereotactic biopsy was performed with pathology of dense fibrous connective tissue consistent with lumpectomy bed, histiocytic inflammatory response associated with microcalcifications and fat necrosis

Fat necrosis calcifications typically demonstrate coarse curvilinear morphology and usually form around the periphery of a radiolucent center of fat (Figs. 16.16a, b, 16.17a, b, 16.18, 16.19a–c, and 16.20a–c). The time of development of fat necrosis is variable ranging from months to years. Although there is a classic appearance of benign calcifications, these calcifications do not always present in their classic form, making assigning benign etiology difficult, particularly when they are more faint in their early stages. When calcifications are indeterminate, careful inspection of prior mammograms may show regression of the calcifications over time or formation of the calcifications around a radiolucent center of fat, suggesting benign etiology [19]. If there is low suspicion based on morphology, monitoring with 6-month follow-up is a reasonable approach. Otherwise, biopsy should be performed for definitive diagnosis of benignity.

Fig. 16.16

(a) An 80-year-old female with history of right breast CA post lumpectomy 20 years prior to the exam. Recent 100 lb weight loss and new palpable abnormality in the right breast. The coarse fat necrosis calcifications were not significantly changed from a prior mammogram 2 years prior but was now better felt by the patient due to her weight loss. (b) Ultrasound of the area of palpable complaint demonstrates expected coarse calcifications and associated posterior acoustic shadowing consistent with fat necrosis

Fig. 16.17

(a) A 72-year-old female with history of lumpectomy 12 years prior. The patient lost 50 lb in the time since her prior mammogram and the patient and physician perceive “hardening” in the lumpectomy bed. (b) Spot magnification views demonstrate coarse, heterogenous fat necrosis calcifications that had been stable over several years. Note multiple biopsy clips localizing prior benign biopsies yielding fat necrosis

Fig. 16.18

Status post right lumpectomy with benign fat necrosis calcifications in the lumpectomy bed. Note the proximity of the calcified mass to the lateral skin making the mass palpable and leading the patient to call it “the rock” in her breast

Fig. 16.19

(a–c) Evolution of fat necrosis. (a) The patient presented to our clinic 1 year following lumpectomy with faint, curvilinear calcifications visualized in the lumpectomy bed. Six months later, the calcifications are coarsening. (b) 24 and 36 months post lumpectomy. Stabilization of calcifications 3 years following surgery. (c) 48 months post lumpectomy

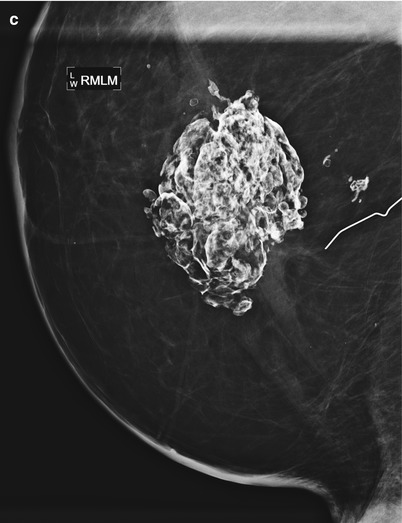

Fig. 16.20

(a) A 73-year-old female with history of right breast cancer status post lumpectomy 2 years prior. Patient is reporting new palpable complaint in the left breast with no mammographic or sonographic correlate. MIP image demonstrates non-mass-like enhancement in the area of palpable complaint. Biopsy was performed and yielded fat necrosis. Nodular enhancement is present in the right lumpectomy cavity. (b) T1 axial non-contrast image demonstrates central fat within the area of enhancement consistent with benign fat necrosis. (c) Right breast mammogram confirms the presence of fat necrosis

Most changes after lumpectomy diminish and regress over time and then remain stable. Stability is defined as the lack of interval change on two successive studies and occurs on average 2–3 years after breast conservation therapy is completed [18]. Fortunately for the breast imager, stability occurs around the time that tumor recurrences begin to appear [14]. Once stability is established, any increase in changes or new findings should be evaluated for tumor recurrence (Fig. 16.21a, b).

Fig. 16.21

(a) 10 years post lumpectomy and radiation therapy with residual skin thickening. (b) Over the following 3 years, the patient developed progressive increase in skin thickening. The patient reported increased breast heaviness. The interval change prompted skin biopsy which revealed dermal fibrosis consistent with scar. Following the biopsy, the patient’s symptoms improved and on the subsequent mammogram the skin thickening returned to postsurgery baseline

Imaging Schedule Post-lumpectomy

Currently there is no widely accepted protocol for appropriate post-lumpectomy surveillance. Although there is consensus on annual mammography of the contralateral breast, recommendations for follow-up mammography on the side of lumpectomy vary by institution and demonstrate considerable geographic variation. At some facilities, a unilateral postsurgical mammogram is performed immediately after lumpectomy but prior to initiation of radiation therapy to evaluate for residual disease at the tumor site. This is particularly recommended in patients who initially presented with extensive area of calcifications on their mammogram or may be helpful for surgical planning if positive margins were present on pathology at the time of lumpectomy. Other institutions obtain a baseline unilateral mammogram immediately following completion of radiation therapy. Some facilities will wait to perform a unilateral mammogram on the side of lumpectomy until 6 months after surgery. Thorough preoperative evaluation of the mammogram and preoperative breast MRI limit the risk for finding unexpected additional disease at the time of surgery and decrease the utility of a mammogram immediately after lumpectomy when it is often painful for the patient. In addition, an irradiated breast can be difficult to position for imaging and may be difficult to compress sufficiently due to patient discomfort.

After the initial unilateral mammogram 6 months post lumpectomy, bilateral mammography is performed at our facility 1 year following lumpectomy and on an annual basis thereafter, unless new imaging findings arise that require closer surveillance. However, various schedules have been proposed for follow-up mammograms after the 12-month study. Some facilities prefer to follow the post-lumpectomy breast at 6 month intervals for up to 3 years. Proponents of this schedule argue that this approach provides the optimum coverage through the “stabilization” period described in the chart. Proponents of extending 6-month follow-up out to 5 years believe that it provides better coverage when the breast transitions from the stabilization phase into the time when there is increasing frequency for recurrence. Some places will modify their schedule to perform more frequent follow-up in the patients that are at higher risk for recurrence based on the characteristics of that individual patient’s cancer. We perform routine magnification views of the lumpectomy for 5 years following lumpectomy, another practice that varies by institution.

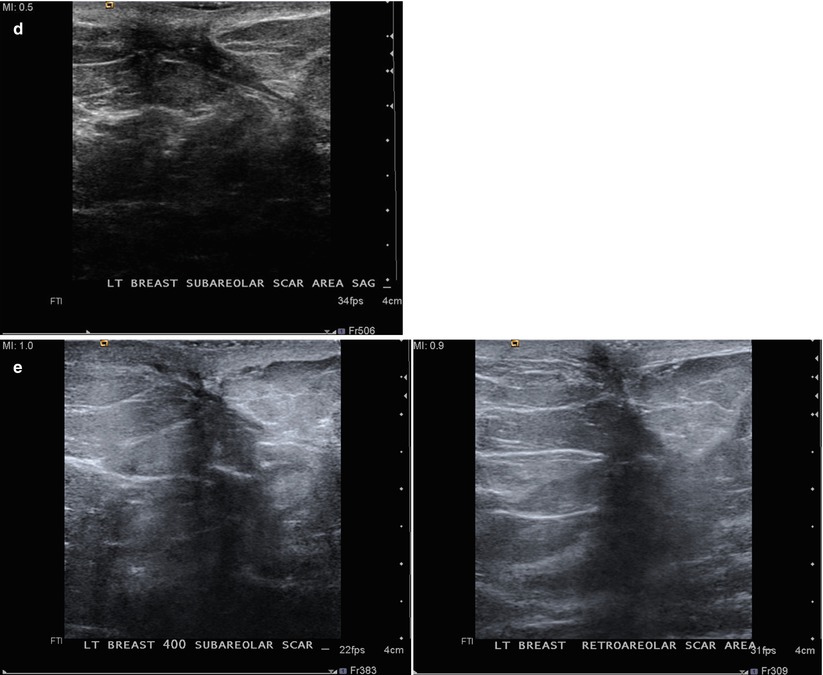

Ultrasound

There are also typical post-lumpectomy changes on sonography. Similar to mammography, familiarity with the expected sonographic appearance after surgery and radiation therapy is useful to avoid misinterpretation. Ultrasound of the lumpectomy bed within the first year after surgery usually demonstrates skin thickening and a fluid collection at the site of surgery, the size of which is variable by patient. Skin thickening after radiation therapy may reach 1 cm or greater [20]. Sonography is helpful in establishing fluid content with a mass seen in the lumpectomy cavity on mammography. The margin of the mass may be well circumscribed, ill defined, or spiculated due to the fibrotic reaction associated with healing (Fig. 16.22a, b). The fluid collection may be round or oval with varying margins (circumscribed, ill defined, or spiculated) and may appear simple or look like a complex cystic mass with septations or echogenic nodules [21] (Fig. 16.23). Aspiration of the postoperative seroma is not recommended and usually reserved for patients that have severe pain at the site or if there is suspected infection due to a tender, tense mass in a patient with fever. Ultrasound can be used for guidance if drainage is indicated. Reaccumulation of fluid following aspiration is common and there is a risk for the development of chronic draining sinuses.

Fig. 16.22

(a) Left lumpectomy 8 years prior. Post-lumpectomy changes in the upper outer breast. (b) Ultrasound appearance of the post-lumpectomy scar area. An irregular hypoechoic area is present with changes extending to the skin. Doppler US does not demonstrate vascularity in the fibrotic scar tissue

Fig. 16.23

Persistent complex postoperative seroma 2 years after lumpectomy. Hyperdense mass in the posterior inner right breast corresponds to a complex fluid collection visualized in the area of the lumpectomy scar on ultrasound. The fluid collection is decreased in size from prior exams but will likely persist on future mammograms

Postoperative masses should remain stable, improve, or resolve. As the fluid is gradually reabsorbed, the residual fibrosis and scarring will be a hypoechoic mass with irregular margins and posterior acoustic shadowing. Identifying this finding beneath the skin scar or identifying a tract between the surgical bed and the skin is helpful in confidently identifying the mass as scar tissue. Sonography is useful in further evaluating mammographic masses as cystic or solid and can also help in further evaluating palpable masses that are obscured by postsurgical changes or dense breast tissue. If a suspicious solid mass is identified, ultrasound can then be used to guide for biopsy. Residual skin thickening is seen in about 20 % of women 2 years after radiation therapy. Most fluid collections resolve within 2 years from the time of surgery. If a mass increases in size, further evaluation with ultrasound and possible biopsy is indicated.

MRI

Screening with breast MRI has high sensitivity, moderate specificity, and high cost when compared with mammography. In published recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging and American College of Radiology, breast MRI may be considered in women with between 15 and 20 % lifetime risk for breast cancer on the basis of personal history of breast or ovarian cancer or biopsy-proven lobular neoplasia or ADH [4]. The American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with breast MRI published in 2007 stated there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening women with a personal history of breast cancer [22]. A study by Morris et al. evaluated breast MRI screening in women with elevated risk of developing breast cancer and negative mammograms. The study included 245 women with personal history of breast cancer. In this group, breast MRI detected mammographically occult cancer in 4 % of the patients [23]. Consultation with referring clinicians can be helpful in selecting a subset of patients with history of breast cancer that is at particularly high risk for recurrence for supplemental screening with breast MRI. Importantly, the impact of breast MRI screening on breast cancer mortality has not been established by randomized clinical trials. As with its use in screening of the high risk for breast cancer population, breast MRI used in screening patients with a personal history of breast cancer should always be performed as an adjunct to mammography as some recurrences, particularly of DCIS, are detected by mammography only.

Recurrence

As therapy for breast cancer continues to improve, the number of long-term survivors is increasing and the population of patients being screened for recurrent disease is increasing. Although there are no randomized trials establishing mortality benefit of screening mammography after breast conservation therapy, the use of screening mammography has been demonstrated to decrease breast cancer mortality and therefore is likely to decrease breast cancer mortality from a second primary tumor. Imaging plays a fundamental role in monitoring breast conservation patients for recurrence and, in combination with clinical history and physical exam, is an important part in optimal surveillance for breast cancer recurrence. It is estimated that 35–50 % of local recurrences will be detected with mammography in the absence of physical findings [24]. Evaluating mammograms in sequence and comparing the current mammogram to not only the prior year but also to mammograms going back several years is critical for detecting subtle findings of recurrence. The goal of surveillance is to detect recurrences at an early time point in order to initiate therapy to improve survival and to maintain a high quality of life.

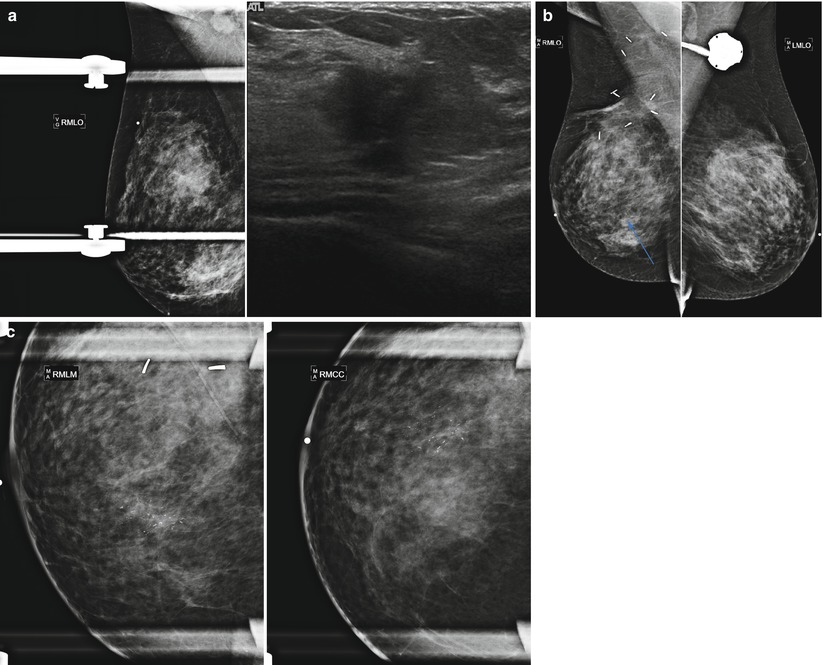

Tumor recurrence can occur locally (ipsilateral treated breast), regionally (ipsilateral lymph nodes), or as a distant metastatic disease. Local tumor recurrence in the ipsilateral breast 5 years after breast-conserving therapy occurs in approximately 7 % of patients with whole breast irradiation and 26 % of patients without whole breast irradiation [25]. Most recurrences occur in the lumpectomy bed, and positive pathologic margins, younger age, higher grade tumor, larger tumor size, negative estrogen receptor status, and involvement of axillary lymph nodes have all been reported to increase the risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence [25–28]. The development of pleomorphic, heterogenous, or linear calcifications, new masses, or skin thickening or increases in size or density of architectural distortion on mammography may indicate breast cancer recurrence and should prompt biopsy (Figs. 16.24a–c, 16.25a, b, 16.26a, b, 16.27a–c, 16.28a, b, 16.29a, b, 16.30a–c, 16.31a, b, and 16.32a, b).

Fig. 16.24

(a) 8 years post left lumpectomy for a 5 mm invasive lobular carcinoma and no positive axillary lymph nodes. Following surgery and XRT, the patient took 5 years of tamoxifen. Stable postsurgical changes in the upper central breast. A small asymmetry in the mid upper central breast was unchanged from multiple prior exams. (b) Nine years post lumpectomy. Interval development of a high-density spiculated mass in the upper central breast. (c) 3 cm anterior to the lumpectomy scar, a 1.1 cm irregular hypoechoic mass with spiculated margins corresponds to the mass seen on mammography. US-guided biopsy yielded infiltrating lobular carcinoma with focal pleomorphic features. The patient underwent left mastectomy

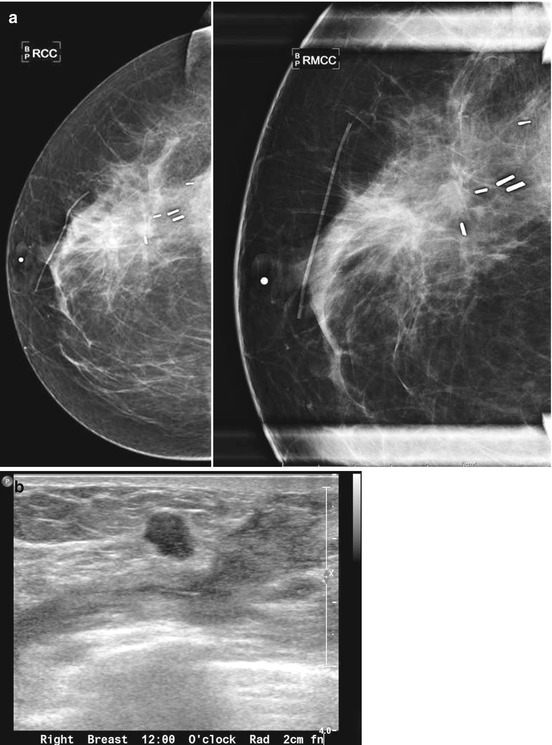

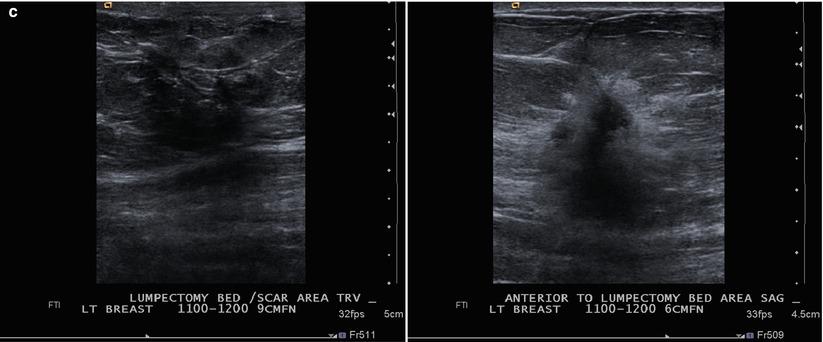

Fig. 16.25

(a) 6 months post lumpectomy. An 8 mm mass is visualized in the lumpectomy bed. (b) US demonstrates a corresponding irregular solid mass. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma

Fig. 16.26

(a) Right breast recurrence: Mammogram on the left was performed 3 years after lumpectomy. Mammogram on the right was performed 5 years after lumpectomy and demonstrates a new 1 cm spiculated mass in the central breast. (b) Spot magnification views and ultrasound demonstrate suspicious spiculated margins to the mass. US-guided core needle biopsy was performed with pathology of invasive carcinoma. The patient declined radiation therapy at the time of her lumpectomy and thus was a candidate for lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the recurrence

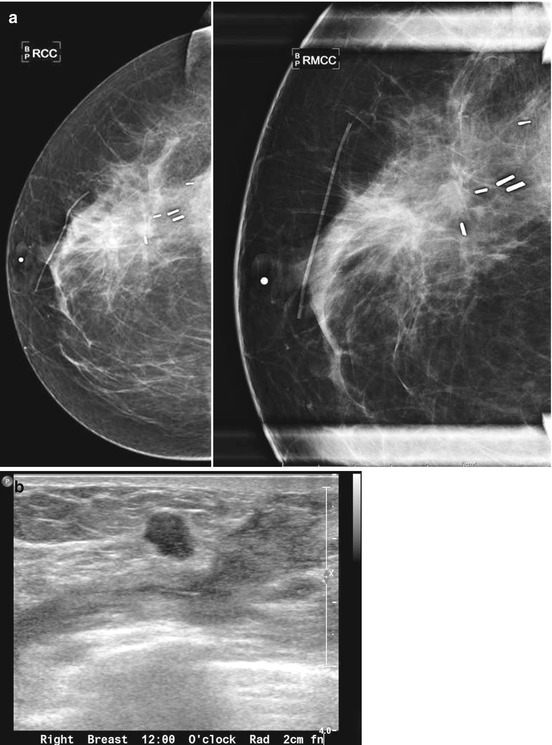

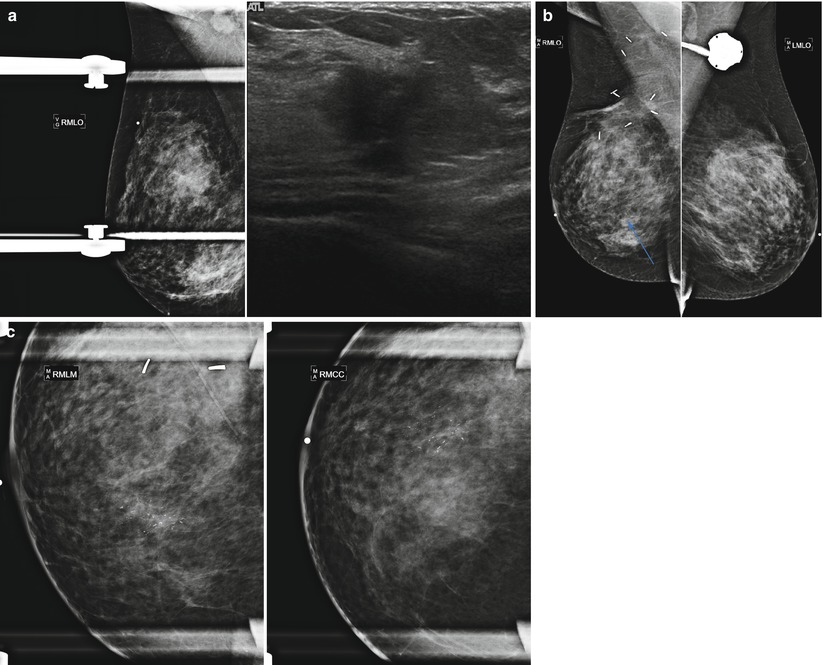

Fig. 16.27

(a) A 72-year-old female status post left lumpectomy for DCIS 1 year prior. (b) Spot magnification views confirm a new mass in the posterior upper outer left breast. (c) A corresponding 8 mm solid mass is seen on ultrasound. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma

Fig. 16.28

(a) 10 years post lumpectomy. New 1 cm mass in the mid lower central left breast. (b) 1.1 cm corresponding hypoechoic mass on US. Biopsy yielded infiltrating mammary carcinoma

Fig. 16.29

(a) Left lumpectomy 3 years prior. New heterogenous calcifications are seen in the posterior aspect of the lumpectomy bed on the spot magnification views. (b) Localization picture for stereotactic biopsy. Pathology demonstrated ductal carcinoma in situ, atypical ductal hyperplasia

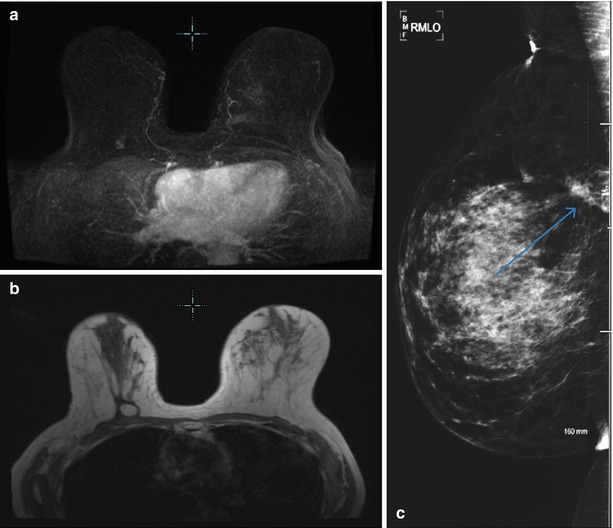

Fig. 16.30

(a) A 42-year-old female present with palpable abnormality in the right breast. Note prominent right axillary lymph node. US demonstrates a corresponding suspicious 1.5 cm mass. Biopsy demonstrated IDC. The patient underwent right lumpectomy and XRT. (b) 6 months following lumpectomy: post-lumpectomy changes are seen in the mid-posterior upper outer right breast. In the central right breast, pleomorphic calcifications span 6 cm. A scar marker overlies the upper outer left breast at the site of prior excision of a fibroadenoma. A left-sided Port-A-Cath is present. (c) Spot magnification views: linear branching calcifications are now seen in the mid central breast. DCIS was found at biopsy

Fig. 16.31

(a) 2 years post right lumpectomy (left), there was no evidence for recurrent disease. 6 months later, the patient felt a new lump in her right axilla (right). (b) Spot magnification views of the lumpectomy bed demonstrate pleomorphic calcifications. An ill-defined hypoechoic mass with echogenic foci (calcifications) in the right 12:00 position measures approximately 3.4 cm. In the right axilla, an abnormal lymph node measures 4.4 cm. Biopsy was performed on both masses with pathology of IDC in the breast and metastatic carcinoma in the axilla

Fig. 16.32

(a) Patient is 17 years post lumpectomy. In a 1-year interval, the patient developed increased density and skin thickening in the retroareolar position. (b) US demonstrates a 1.5 cm mass with angular margins and skin thickening. Biopsy yielded invasive carcinoma

Tumor recurrence rarely occurs in the first 2 years following treatment [18]. Changes in the mammogram in that time are more likely alterations from benign processes. Tumor recurrence in the postoperative site or quadrant peaks at a rate of 2.5 % between 2 and 6 years after breast conservation therapy. Recurrent cancers at the original tumor site usually result from failure to eradicate the original cancer and usually occur sooner than tumor developing elsewhere in the breast. Recurrence more than 10 years after therapy will more likely occur outside the treated area and likely represent new malignancies. Recurrent tumor is usually treated with salvage mastectomy. However, if the patient did not undergo radiation therapy in their initial therapy, surgical re-excision with subsequent radiation is a possible alternative.

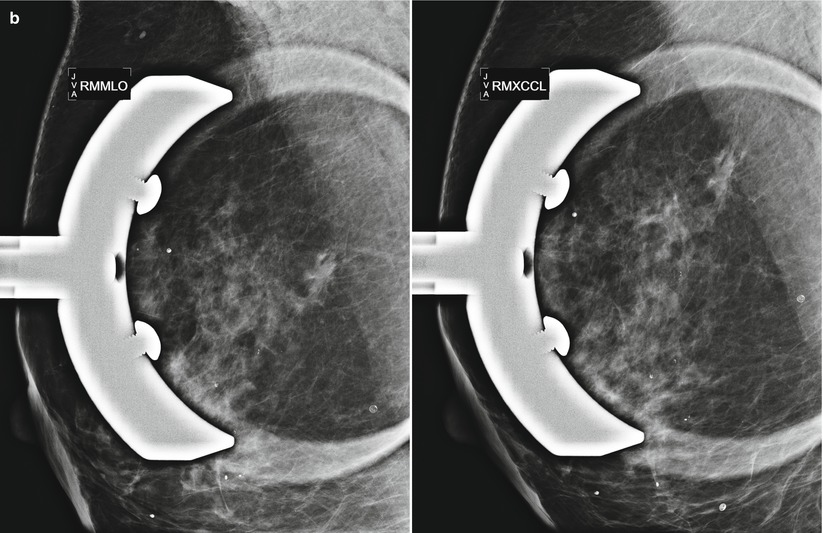

Breast cancer in the contralateral breast of women with known history of breast cancer may represent a new primary or a metastasis from the original breast cancer (Figs. 16.33a–d, 16.34a–d, and 16.35a–c). Cancer with different pathology from the original cancer or a cancer with an associated in situ component is classified as new primaries. The risk for a metachronous, contralateral second primary breast cancer is estimated at 0.5–1.0 % per year [29]. Factors that increase the risk include a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, young age at first primary, family history of breast cancer, lobular histology for first primary breast cancer, and prior radiation exposure [30–32]. Treatment of estrogen-positive primary cancers with tamoxifen can decrease risk for contralateral breast cancer by 50 % [25]. Adjuvant endocrine therapy trials incorporating an aromatase inhibitor document an even greater reduction in the occurrence of contralateral breast cancer [33]. Knowledge of the receptor status of the patient’s original tumor and possible subsequent endocrine therapy can be helpful to breast imagers in the pretest probability assessment for risk for recurrent disease.

Fig. 16.33

(a) Left lumpectomy 11 years prior. Post-lumpectomy changes in the upper outer left breast. A new 1 cm asymmetry is visualized in the posterior upper outer right breast. (b) Spot magnification views of the asymmetry in the far posterior breast. (c) A corresponding 1.1 cm hypoechoic mass is identified in the right posterior breast on US. Note is also made of residual fluid in the left lumpectomy bed. Biopsy of the right breast mass had pathology of invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient opted for bilateral mastectomies. (d) 1 year following surgery, the patient presented with a new palpable abnormality in the far lateral right chest wall. A corresponding 1.4 cm hypoechoic mass was visualized with similar pathology and biomarkers as the prior right breast cancer

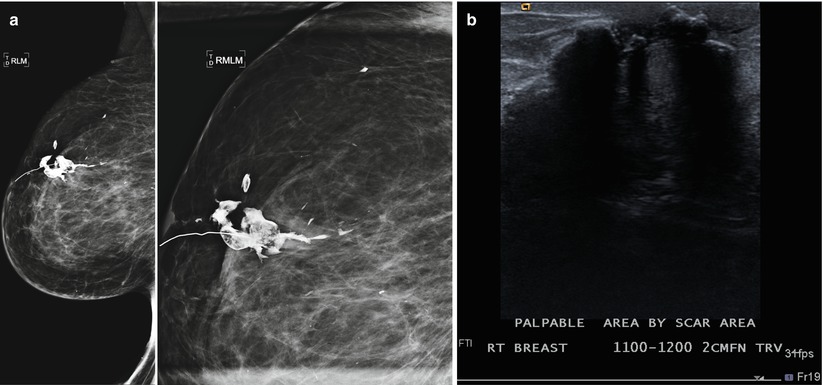

Fig. 16.34

(a) 7 years post right lumpectomy. New heterogenous calcifications are visualized in the posterior upper left breast. (b) Spot magnification views. Stereotactic biopsy demonstrated in situ carcinoma. (c) 6-month follow-up after lumpectomy demonstrates no residual suspicious calcifications in the lumpectomy bed. (d) 1 year post left lumpectectomy. Expected post surgical changes are present in the posterior upper outer left breast and right retroareolar position (8 years following surgery). Note: Asymmetric glandular tissue in the anterior inferior left breast is stable from prior mammogram

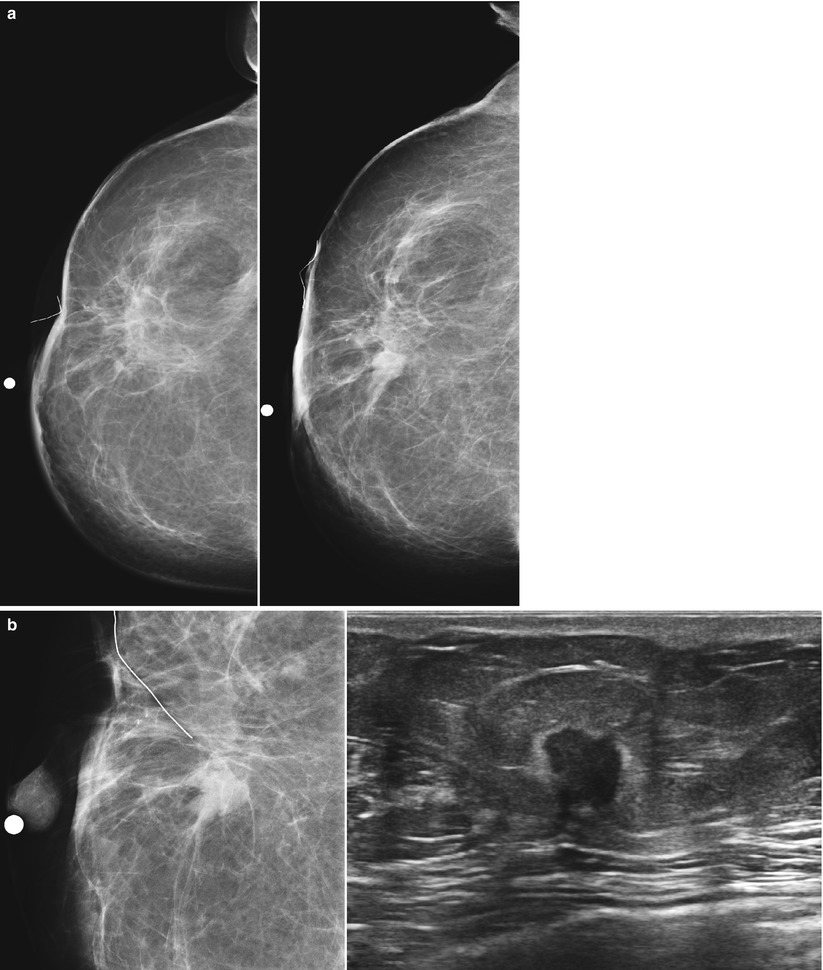

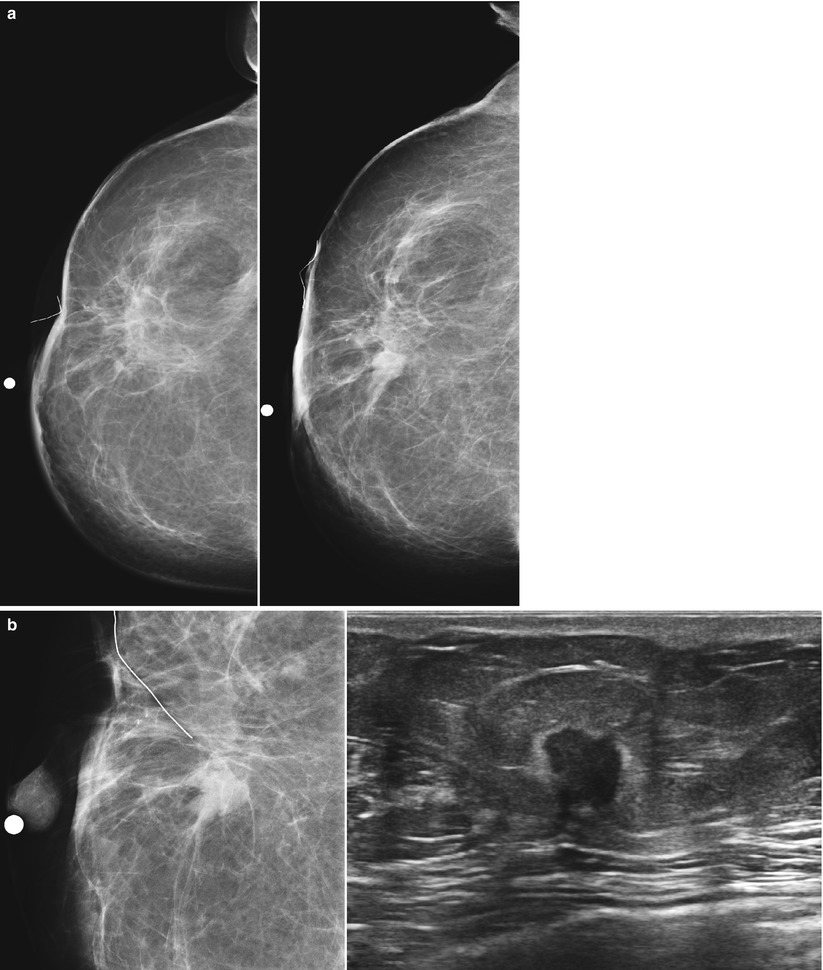

Fig. 16.35

(a) 6 years post right lumpectomy for 1.5 cm tubular carcinoma. Stable post-lumpectomy changes on the right. New subtle architectural distortion is seen in the posterior upper left breast. (b) The area is less prominent on spot compression views. However, a 1.2 cm suspicious mass is identified with ultrasound. Pathology was IDC with focal lobular growth pattern. (c) Post-contrast subtraction MRI images: in addition to the cancer in the posterior upper left breast, multiple additional abnormal enhancing masses extending anterior from the known cancer are seen on MRI. The total area of abnormal enhancement measures 6.2 cm. There was no evidence for recurrent disease in the right breast

Calcifications are an important marker for new or recurrent cancer following lumpectomy. Up to 43 % of mammographically detected cases of recurrent cancer manifest as microcalcifications [34]. The presence of pleomorphic calcifications is concerning for recurrent or residual malignancy and biopsy should be performed. In general, increasing microcalcifications in the lumpectomy bed are worrisome for breast cancer recurrence, unless the calcifications are increasing in coarseness as would be seen in fat necrosis or dystrophic calcifications. Ultrasound is limited in the evaluation of calcifications and therefore is not recommended as the primary imaging method to evaluate for recurrence. Although sonography alone is not recommended as the primary means of evaluation for recurrence, sonography can be a useful adjunctive study for supplemental screening [35].

Some patient present with perceived changes in their lumpectomy bed. The patient may describe the scar becoming more firm or larger. Usually these subjective changes are due to scar tissue or fat necrosis. If evaluation with mammography and ultrasound fails to demonstrate interval change, evaluation with breast MRI may be helpful in discriminating postsurgical scarring from recurrent tumor at the lumpectomy site [36].

Postmastectomy

Mastectomy is the surgical removal of the entire breast tissue. This is performed in women with breast cancer who cannot be adequately treated with breast conservation therapy or in women who prefer this method for treatment of their cancer. Also, women who have a high risk for developing breast cancer such as BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 carriers can opt to have prophylactic mastectomies. The risk of developing a breast malignancy is significantly reduced but not entirely eliminated in patients who undergo prophylactic mastectomy or any mastectomy for that matter, because a small amount of residual breast tissue remains. The lack of a distinct boundary between the breast and adjacent adipose tissue makes the removal of all breast tissue difficult [37].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree