The Normal Thyroid

The normal adult thyroid gland weighs 16 to 25 g and is composed of two lateral lobes and an isthmus (Fig. 2.1). Because it derives from an evagination of the base of the tongue and migrates down the anterior neck, there is usually a thin remnant of the track of descent known as the pyramidal lobe at the superior end of the isthmus [1]. In the normal mature gland, each lobe has a pointed superior pole and a blunt, rounded inferior pole. Each lobe measures approximately 4 cm in the superoinferior plane, 2.5 cm in the mediolateral plane, and 2 cm in the anteroposterior plane [2]. The isthmus is more variable in size; it usually measures from 1 to 2 cm mediolaterally but can vary from 0.5 to 2 cm in the superoinferior plane. There are usually several small lymph nodes around the isthmus. The dominant node is known as the “delphian node” because of its prophetic role in patients with thyroid cancer.

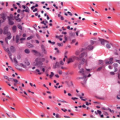

Lobules of thyroid parenchyma are composed of follicles. The lobulation is subtle, but the fibroconnective tissue that define the lobules is important to recognize (Fig. 2.2, e-Figs. 2.1 and 2.2), since they are lost in neoplastic proliferations and they can be accentuated in inflammatory lesions.

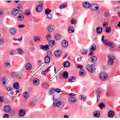

The follicles of the normal gland are lined by follicular epithelial cells that are heterogeneous. They are mainly cuboidal cells (Fig. 2.3, e-Fig. 2.3), the most active are columnar cells with basal nuclei, and some follicles have areas of flat attenuated epithelium. The follicular cells maintain adhesion to the basement membrane surrounding the follicle. The follicles contain thyroglobulin that is usually stored as pale and homogeneous colloid. Colloid often retracts from the surrounding tissue during fixation, but when it is being actively resorbed for thyroid hormone synthesis, the proteolytic cleavage induced by the resorbing cell causes a peculiar scalloping effect (Fig. 2.4, e-Fig. 2.4).

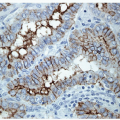

Scattered within this parenchyma at the junction of the upper third and lower two-thirds of each lateral lobe are the C cells that produce calcitonin [3, 4]. These cells were initially described by Karl Hürthle in 1904 [5], although his name has come to be associated with something completely different, oncocytic follicular cells. C cells are so called because they have clear cytoplasm and because they make calcitonin. These neuroendocrine cells are difficult to recognize on routine sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (e-Fig. 2.5) but are readily identified by calcitonin immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2.5, e-Fig. 2.6). They are usually isolated as single cells within

the basement membrane of a follicle, but they may form small cluster of two or three cells. They are not usually found in the isthmus or lower poles of the lobes.

the basement membrane of a follicle, but they may form small cluster of two or three cells. They are not usually found in the isthmus or lower poles of the lobes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree