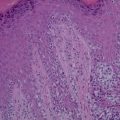

Figure 6.1

Rhomboid flap

Limberg and his followers (including us) use a bit of ‘surgical license’ when referring to the ‘rhomboid’ shape. Because, mathematically speaking, a parallelogram with sides of equal length (equilateral) is a rhombus but not a rhomboid (the latter does not have equal sides).

A rhombus has equal sides and 60° and 120° angles. In general, any quadrilateral whose two diagonals are perpendicular is called a kite. Every rhombus is a kite, and any quadrilateral that is both a kite and parallelogram is mathematically a rhombus. Therefore surgically speaking, we are using the term ‘rhomboid’ to mean ‘rhombus.’ As Euclid, the Greek mathematician clarified [4]:

Of quadrilateral figures, a square is that which is both equilateral and right-angled; an oblong that which is right-angled but not equilateral; a rhombus that which is equilateral but not right-angled; and a rhomboid that which has its opposite sides and angles equal to one another but is neither equilateral nor right-angled. And let quadrilaterals other than these be called trapezia.

The rhomboid flap is a reliable, versatile, and widely used tool in head and neck surgery [5]. Although its geometry is well described, the mechanics of the flap when planned in the classical fashion do not always take into account the RSTL or skin creases. In this case study, I discuss the modified rhomboid flap and its applications for head and neck surgery after skin cancer. More specifically, the unique design of the modified rhomboid flap makes an especially good choice for surgery to the ala nasi and the anatomy and planning are detailed in this regard.

The Modified Rhomboid Flap

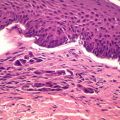

In the classical design of a Limberg flap, a rhombus-shaped segment of skin containing the lesion is excised. A flap is created by incising the skin at a 180° angle relative to the short diagonal of the rhombus and then extending this excision parallel to one of the adjacent sides of the rhombus. This area is then undermined and the flap thus created is rotated into the surgical defect (Fig. 6.2) [6]. One of the interesting things we note in the rhomboid flap is that the flap itself closes only a portion of the defect while the 60° angle closest to the point about which the flap is rotated is closed directly. In other words, one is still closing a 60° ‘ellipse’ under tension [7].

There are two fundamental problems with the traditional rhomboid flap. The cutting out of a rhomboid shape does not take into account skin tension lines. Secondly, the closure line of the flap is also not orientated along the RSTL which is one of the guiding principles of cutaneous plastic surgery. Larrabee, who has made a remarkable contribution to the modern understanding of the dynamics of several different random flaps spent time analyzing rhomboid flaps. He concluded that the actual position of the final scars is more variable than the changes in length of the flap and is related to local tissue characteristics, e.g. the ease of tissue advancement from different directions. The most important result from his study was a clarification of the distribution of tension in a 60° rhomboid flap. Most of the tension is located at the closure of the donor site.

Figure 6.2

Rhomboid flap mechanism illustrated

In other words, an ideally designed rhomboid flap would have the RSTL bisecting the 60° angle of the flap. This is the basis of the modified rhomboid flap.

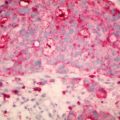

In the modified rhomboid flap, the lesion is cut out without attempting to create a rhomboid shape (therefore no unnecessary tissue is excised). The 60° flap is planned with the 60° flap angle being bisected by RSTL. Care is taken to ensure that the limbs of the flap are equilateral. Figure 6.3 illustrates a modified rhomboid flap on the cheek (unlike in Fig. 6.2 the shape is not made into a rhomboid; rather the defect is simply cut out – in this case a circular lesion – the black line in the image indicates the RSTL in that location which bisects the 60° flap). And Fig. 6.3 illustrates the difference between a traditional rhomboid flap and the modified version – in the latter, the RSTL or skin creases bisect the 60° flap. However, in the modified rhomboid flap, there is no need to cut additional tissue for the sake of creating a rhomboid shape.

Figure 6.3

(a–b) Modified rhomboid flap is bisected by the RSTL

Case Studies

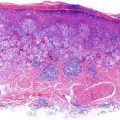

Case 1: A biopsy-proven basal-cell carcinoma was excised from the R ala nasi of a 71-year-old woman and the defect was closed with a modified rhomboid flap. I simply cut out the lesion with adequate margins, then plan the modified rhomboid flap using the three essential principles in my method: flap angle bisected by the nasolabial crease; flap lengths equal; flap lengths somewhere between radius and diameter (Fig. 6.4). The end result is shown with the flap sutured in place (Fig. 6.5). The unique shape of the ala nasi and the adjacent naso-labial crease ensures that there is no scar visible post-op as all the sutures are in skin creases or the margin of the ala nasi.

Figure 6.4

Modified rhomboid flap of the ala nasi plan